Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Agriculture

includes the farming and processing of different crops for market, as well as livestock, and dairy products in the United States and Abroad, including government programs that support/regulate agriculture as well as the science of agriculture today.

Agriculture in the United States including advancements in Agricultural Machinery used in farming, as well as Agricultural Commerce: from the farm to your local supermarket!

YouTube Video: Farm to Market: Cotton (clips)

Pictured: LEFT: Modern Farming Equipment: L-R: John Deere 7800 tractor with Houle slurry trailer, Case IH combine harvester, New Holland FX 25 forage harvester with corn head. RIGHT: Different Breeds of Dairy Cattle include Holstein, Jersey, Brown Swiss, Guernsey, Ayrshire, and Milking Shorthorn.

Agriculture is a major industry in the United States, which is a net exporter of food. As of the 2007 census of agriculture, there were 2.2 million farms, covering an area of 922 million acres (3,730,000 km2), an average of 418 acres (1.69 km2) per farm.

Although agricultural activity occurs in most states, it is particularly concentrated in the Great Plains, a vast expanse of flat, arable land in the center of the United States and in the region around the Great Lakes known as the Corn Belt.

The United States has been a leader in seed improvement i.e. hybridization and in expanding uses for crops from the work of George Washington Carver to the development of bioplastics and biofuels.

The mechanization of farming, intensive farming, has been a major theme in U.S. history, including John Deere's steel plow, Cyrus McCormick's mechanical reaper, Eli Whitney's cotton gin to the widespread success of the Fordson tractor and the combine harvesters first made from them.

Modern agriculture in the U.S. ranges from the common hobby farms, small-scale producers to large commercial farming covering thousands of acres of cropland or rangeland.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

___________________________________________________________________________

Agricultural equipment is any kind of machinery used on a farm to help with farming. The best-known example of this kind is the tractor.

Click on any of the following for amplification:

Agricultural Marketing: includes the services involved in moving agricultural product from the farm to the consumer.

Numerous interconnected activities are involved in doing this, such as planning production, growing and harvesting, grading, packing, transport, storage, agro- and food processing, distribution, advertising and sale.

Some definitions would even include “the acts of buying supplies, renting equipment, (and) paying labor", arguing that marketing is everything a business does. Such activities cannot take place without the exchange of information and are often heavily dependent on the availability of suitable finance.

Marketing systems are dynamic; they are competitive and involve continuous change and improvement. Businesses that have lower costs, are more efficient, and can deliver quality products, are those that prosper. Those that have high costs, fail to adapt to changes in market demand and provide poorer quality are often forced out of business.

Marketing has to be customer-oriented and has to provide the farmer, transporter, trader, processor, etc. with a profit. This requires those involved in marketing chains to understand buyer requirements, both in terms of product and business conditions.

In Western countries considerable agricultural marketing support to farmers is often provided.

In the USA, for example, the USDA operates the Agricultural Marketing Service. Support to developing countries with agricultural marketing development is carried out by various donor organizations and there is a trend for countries to develop their own Agricultural Marketing or Agribusiness units, often attached to ministries of agriculture. Activities include market information development, marketing extension, training in marketing and infrastructure development.

Since the 1990s trends have seen the growing importance of supermarkets and a growing interest in contract farming, both of which impact significantly on the way in which marketing takes place.

For more about Agricultural Marketing, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

Although agricultural activity occurs in most states, it is particularly concentrated in the Great Plains, a vast expanse of flat, arable land in the center of the United States and in the region around the Great Lakes known as the Corn Belt.

The United States has been a leader in seed improvement i.e. hybridization and in expanding uses for crops from the work of George Washington Carver to the development of bioplastics and biofuels.

The mechanization of farming, intensive farming, has been a major theme in U.S. history, including John Deere's steel plow, Cyrus McCormick's mechanical reaper, Eli Whitney's cotton gin to the widespread success of the Fordson tractor and the combine harvesters first made from them.

Modern agriculture in the U.S. ranges from the common hobby farms, small-scale producers to large commercial farming covering thousands of acres of cropland or rangeland.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

- Major agricultural products

- Farm type or majority enterprise type

- Governance

- Employment

- Occupational safety and health

- Women in agriculture

- See also:

- 2010 United States tomato shortage

- Agribusiness

- Beekeeping in the United States

- Electrical energy efficiency on United States farms

- Genetic engineering in the United States

- Poultry farming in the United States

- Soil in the United States

- History of agriculture in the United States

- List of largest producing countries of agricultural commodities

- List of turkey meat producing companies in the United States

- Banana production in the United States

___________________________________________________________________________

Agricultural equipment is any kind of machinery used on a farm to help with farming. The best-known example of this kind is the tractor.

Click on any of the following for amplification:

- Tractor and power

- Soil cultivation

- Planting

- Fertilizing & Pest Control

- Irrigation

- Produce sorter

- Harvesting / post-harvest

- Hay making

- Loading

- Milking

- Animal Feeding

- Other

- Obsolete farm machinery

Agricultural Marketing: includes the services involved in moving agricultural product from the farm to the consumer.

Numerous interconnected activities are involved in doing this, such as planning production, growing and harvesting, grading, packing, transport, storage, agro- and food processing, distribution, advertising and sale.

Some definitions would even include “the acts of buying supplies, renting equipment, (and) paying labor", arguing that marketing is everything a business does. Such activities cannot take place without the exchange of information and are often heavily dependent on the availability of suitable finance.

Marketing systems are dynamic; they are competitive and involve continuous change and improvement. Businesses that have lower costs, are more efficient, and can deliver quality products, are those that prosper. Those that have high costs, fail to adapt to changes in market demand and provide poorer quality are often forced out of business.

Marketing has to be customer-oriented and has to provide the farmer, transporter, trader, processor, etc. with a profit. This requires those involved in marketing chains to understand buyer requirements, both in terms of product and business conditions.

In Western countries considerable agricultural marketing support to farmers is often provided.

In the USA, for example, the USDA operates the Agricultural Marketing Service. Support to developing countries with agricultural marketing development is carried out by various donor organizations and there is a trend for countries to develop their own Agricultural Marketing or Agribusiness units, often attached to ministries of agriculture. Activities include market information development, marketing extension, training in marketing and infrastructure development.

Since the 1990s trends have seen the growing importance of supermarkets and a growing interest in contract farming, both of which impact significantly on the way in which marketing takes place.

For more about Agricultural Marketing, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

United States Department of Agriculture and Food and Drug Administration

YouTube Video about Food Safety Audit*

*--The University of California Small Farm Program serves a diversity of small family farms. For more information please visit our website at: http://sfp.ucdavis.edu/

Pictured: LEFT: Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Services: RIGHT: Nutrition Facts label required by the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), also known as the Agriculture Department, is the U.S. federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, agriculture, forestry, and food. It aims to meet the needs of farmers and ranchers, promote agricultural trade and production, work to assure food safety, protect natural resources, foster rural communities and end hunger in the United States and internationally.

Approximately 80% of USDA's $140 billion budget goes to the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) program. The largest component of the FNS budget is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as the Food Stamp program), which is the cornerstone of USDA's nutrition assistance.

Many of the programs concerned with the distribution of food and nutrition to people of America and providing nourishment as well as nutrition education to those in need are run and operated under the USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Activities in this program include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides healthy food to over 40 million low-income and homeless people each month. USDA is a member of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, where it is committed to working with other agencies to ensure these mainstream benefits are accessed by those experiencing homelessness.

The USDA also is concerned with assisting farmers and food producers with the sale of crops and food on both the domestic and world markets. It plays a role in overseas aid programs by providing surplus foods to developing countries. This aid can go through USAID, foreign governments, international bodies such as World Food Program, or approved nonprofits.

The Agricultural Act of 1949, section 416 (b) and Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954, also known as Food for Peace, provides the legal basis of such actions. The USDA is a partner of the World Cocoa Foundation.

For further amplification, click on any of the blue hyperlinks below:

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA or USFDA) is a federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, one of the United States federal executive departments. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of the following:

The FDA was empowered by the United States Congress to enforce the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which serves as the primary focus for the Agency; the FDA also enforces other laws, notably Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act and associated regulations, many of which are not directly related to food or drugs.

These include regulating lasers, cellular phones, condoms and control of disease on products ranging from certain household pets to sperm donation for assisted reproduction.

The FDA is led by the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Commissioner reports to the Secretary of Health and Human Services.

The FDA has its headquarters in unincorporated White Oak, Maryland.

The agency also has 223 field offices and 13 laboratories located throughout the 50 states, the United States Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. In 2008, the FDA began to post employees to foreign countries, including China, India, Costa Rica, Chile, Belgium, and the United Kingdom.

Click here for Department of Health and Human Services

Click here for further amplification about the FDA.

Approximately 80% of USDA's $140 billion budget goes to the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) program. The largest component of the FNS budget is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as the Food Stamp program), which is the cornerstone of USDA's nutrition assistance.

Many of the programs concerned with the distribution of food and nutrition to people of America and providing nourishment as well as nutrition education to those in need are run and operated under the USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Activities in this program include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides healthy food to over 40 million low-income and homeless people each month. USDA is a member of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, where it is committed to working with other agencies to ensure these mainstream benefits are accessed by those experiencing homelessness.

The USDA also is concerned with assisting farmers and food producers with the sale of crops and food on both the domestic and world markets. It plays a role in overseas aid programs by providing surplus foods to developing countries. This aid can go through USAID, foreign governments, international bodies such as World Food Program, or approved nonprofits.

The Agricultural Act of 1949, section 416 (b) and Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954, also known as Food for Peace, provides the legal basis of such actions. The USDA is a partner of the World Cocoa Foundation.

For further amplification, click on any of the blue hyperlinks below:

- History

- Origins

Formation and subsequent history

- Origins

- Organization, budget and tasks

- Discrimination

- Pigford v. Glickman

Reopening of case

- Pigford v. Glickman

- Related legislation

- See also:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Endangered Species Act

- Title 7 of the Code of Federal Regulations

- Title 9 of the Code of Federal Regulations

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act

- National Transportation Safety Board

- The Wildlife Society

- United States Agricultural Society

- US Fish and Wildlife Service

- USDA home loan

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA or USFDA) is a federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, one of the United States federal executive departments. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of the following:

- food safety,

- tobacco products,

- dietary supplements,

- prescription and over-the-counter pharmaceutical drugs (medications),

- vaccines,

- biopharmaceuticals,

- blood transfusions,

- medical devices,

- electromagnetic radiation emitting devices (ERED),

- cosmetics,

- animal foods & feed

- and veterinary products.

The FDA was empowered by the United States Congress to enforce the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which serves as the primary focus for the Agency; the FDA also enforces other laws, notably Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act and associated regulations, many of which are not directly related to food or drugs.

These include regulating lasers, cellular phones, condoms and control of disease on products ranging from certain household pets to sperm donation for assisted reproduction.

The FDA is led by the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Commissioner reports to the Secretary of Health and Human Services.

The FDA has its headquarters in unincorporated White Oak, Maryland.

The agency also has 223 field offices and 13 laboratories located throughout the 50 states, the United States Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. In 2008, the FDA began to post employees to foreign countries, including China, India, Costa Rica, Chile, Belgium, and the United Kingdom.

Click here for Department of Health and Human Services

Click here for further amplification about the FDA.

History of Agriculture, including a Timeline of Agriculture and Food Technology

YouTube Video about the History of Agriculture Technology

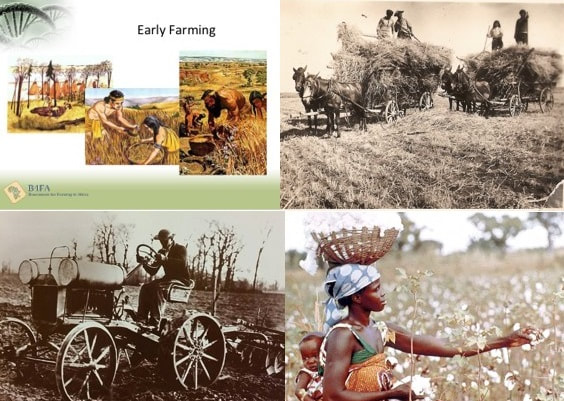

Pictured: Clockwise, from Upper Left: ancient farming techniques; horse-drawn farming; picking cotton by hand; and an early tractor used for plowing a field.

Click here for historical timeline of agriculture and food technology.

The history of agriculture covers the domestication of plants and animals and the development and dissemination of techniques for raising them productively.

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin.

Wild grains were collected and eaten from at least 20,000 BC. From around 9,500 BC, the eight Neolithic founder crops--emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas, and flax—were cultivated in the Levant.

Rice was domesticated in China between 11,500 and 6,200 BC, followed by mung, soy and azuki beans.

Pigs were domesticated in Mesopotamia around 13,000 BC, followed by sheep between 11,000 and 9,000 BC. Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan around 8,500 BC.

Sugarcane and some root vegetables were domesticated in New Guinea around 7,000 BC. Sorghum was domesticated in the Sahel region of Africa by 5,000 BC.

In the Andes of South America, the potato was domesticated between 8,000 and 5,000 BC, along with beans, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Bananas were cultivated and hybridized in the same period in Papua New Guinea.

In Mesoamerica, wild teosinte was domesticated to maize by 4,000 BC. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 3,600 BC. Camels were domesticated late, perhaps around 3,000 BC.

In the Middle Ages, both in the Islamic world and in Europe, agriculture was transformed with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees such as the orange to Europe by way of Al-Andalus.

After 1492, the Columbian exchange brought New World crops such as maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnips, and livestock including horses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the Americas.

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers were introduced soon after the Neolithic Revolution and developed much further in the past 200 years, starting with the British Agricultural Revolution.

Since 1900, agriculture in the developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as human labor has been replaced by mechanization, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding.

The Haber-Bosch process allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields. Modern agriculture has raised social, political, and environmental issues including water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs and farm subsidies.

In response, organic farming developed in the twentieth century as a consciously pesticide-free alternative.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the History of Agriculture:

The history of agriculture covers the domestication of plants and animals and the development and dissemination of techniques for raising them productively.

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin.

Wild grains were collected and eaten from at least 20,000 BC. From around 9,500 BC, the eight Neolithic founder crops--emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas, and flax—were cultivated in the Levant.

Rice was domesticated in China between 11,500 and 6,200 BC, followed by mung, soy and azuki beans.

Pigs were domesticated in Mesopotamia around 13,000 BC, followed by sheep between 11,000 and 9,000 BC. Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan around 8,500 BC.

Sugarcane and some root vegetables were domesticated in New Guinea around 7,000 BC. Sorghum was domesticated in the Sahel region of Africa by 5,000 BC.

In the Andes of South America, the potato was domesticated between 8,000 and 5,000 BC, along with beans, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Bananas were cultivated and hybridized in the same period in Papua New Guinea.

In Mesoamerica, wild teosinte was domesticated to maize by 4,000 BC. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 3,600 BC. Camels were domesticated late, perhaps around 3,000 BC.

In the Middle Ages, both in the Islamic world and in Europe, agriculture was transformed with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees such as the orange to Europe by way of Al-Andalus.

After 1492, the Columbian exchange brought New World crops such as maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnips, and livestock including horses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the Americas.

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers were introduced soon after the Neolithic Revolution and developed much further in the past 200 years, starting with the British Agricultural Revolution.

Since 1900, agriculture in the developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as human labor has been replaced by mechanization, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding.

The Haber-Bosch process allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields. Modern agriculture has raised social, political, and environmental issues including water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs and farm subsidies.

In response, organic farming developed in the twentieth century as a consciously pesticide-free alternative.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the History of Agriculture:

American Farm Bureau Federation

YouTube Video: President Donald Trump speaks at American Farm Bureau Federation's convention (ABC News)

Pictured below: American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF)

Click here for a List of Farm Bureaus:

The American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), more commonly referred to as Farm Bureau (FB), is an independent, non-governmental, voluntary organization governed by and representing farm and ranch families united for the purpose of analyzing their problems and formulating action to achieve educational improvement, economic opportunity and social advancement and, thereby, to promote the national well-being.

Farm Bureau is local, county, state, national and international in its scope and influence and is non-partisan, non-sectarian and non-secret in character. Farm Bureau is the voice of agricultural producers at all levels. AFBF is headquartered in Washington, D.C. There are 50 state affiliates and one in Puerto Rico.

Advocacy

Policy is changing constantly, and it has a direct impact on farmers and ranchers. Having a voice – a seat at the table and an impact on policy – is critical. Beginning at the grassroots level and involving Farm Bureau members' advocacy efforts across the country, all of agriculture speaks with one voice through the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Education

The American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture works to build awareness, understanding and a positive perception of agriculture through education. The Foundation is creating agriculturally literate citizens through our educational programs, grants, scholarships, classroom curriculum, and volunteer training.

The Foundation also builds relationships with educational institutions to introduce agricultural education tools and resources, and encourages adoption at the community, county, state, and national level.

Empowerment:

From its beginnings nearly a century ago, Farm Bureau has existed to give members the tools they need to succeed. That can mean financial expertise, communication skills, advocacy opportunities, training and opportunities to network with and learn from fellow farmers and ranchers. It all adds up to helping America's farmers and ranchers stay strong and prosperous.

Membership:

For nearly a century Farm Bureau members have joined together from coast to coast and become the Voice of Agriculture. Farm Bureau continues to evolve to serve the needs of members and their families on and off the farm or ranch.

The Farm Bureau legacy includes leadership within local communities, advocacy on rural issues, public service and outreach, agriculture literacy and environmental initiatives that protect the environment and preserve its productive beauty for the next generation to utilize and enjoy.

Joining Farm Bureau provides your family with exclusive discounts on national brands, plus valued member benefits.

Lobbying

AFBF made The Hill's 2017 list of top association lobbying groups and was dubbed a "farm policy powerhouse" for tracking issues like crop insurance, voluntary labeling requirements for bioengineered foods and disease surveillance response. "And that only scratches the surface of its work," according to The Hill.11

AFBF supported the Fighting Hunger Incentive Act of 2014 (H.R. 4719; 113th Congress), a bill that would amend the Internal Revenue Code to permanently extend and expand certain expired provisions that provided an enhanced tax deduction for businesses that donated their food inventory to charitable organizations. AFBF argued that without the tax write-off, "it is cheaper in most cases for these types of businesses to throw their food away than it is to donate the food".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the American Farm Bureau Federation:

The American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), more commonly referred to as Farm Bureau (FB), is an independent, non-governmental, voluntary organization governed by and representing farm and ranch families united for the purpose of analyzing their problems and formulating action to achieve educational improvement, economic opportunity and social advancement and, thereby, to promote the national well-being.

Farm Bureau is local, county, state, national and international in its scope and influence and is non-partisan, non-sectarian and non-secret in character. Farm Bureau is the voice of agricultural producers at all levels. AFBF is headquartered in Washington, D.C. There are 50 state affiliates and one in Puerto Rico.

Advocacy

Policy is changing constantly, and it has a direct impact on farmers and ranchers. Having a voice – a seat at the table and an impact on policy – is critical. Beginning at the grassroots level and involving Farm Bureau members' advocacy efforts across the country, all of agriculture speaks with one voice through the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Education

The American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture works to build awareness, understanding and a positive perception of agriculture through education. The Foundation is creating agriculturally literate citizens through our educational programs, grants, scholarships, classroom curriculum, and volunteer training.

The Foundation also builds relationships with educational institutions to introduce agricultural education tools and resources, and encourages adoption at the community, county, state, and national level.

Empowerment:

From its beginnings nearly a century ago, Farm Bureau has existed to give members the tools they need to succeed. That can mean financial expertise, communication skills, advocacy opportunities, training and opportunities to network with and learn from fellow farmers and ranchers. It all adds up to helping America's farmers and ranchers stay strong and prosperous.

Membership:

For nearly a century Farm Bureau members have joined together from coast to coast and become the Voice of Agriculture. Farm Bureau continues to evolve to serve the needs of members and their families on and off the farm or ranch.

The Farm Bureau legacy includes leadership within local communities, advocacy on rural issues, public service and outreach, agriculture literacy and environmental initiatives that protect the environment and preserve its productive beauty for the next generation to utilize and enjoy.

Joining Farm Bureau provides your family with exclusive discounts on national brands, plus valued member benefits.

Lobbying

AFBF made The Hill's 2017 list of top association lobbying groups and was dubbed a "farm policy powerhouse" for tracking issues like crop insurance, voluntary labeling requirements for bioengineered foods and disease surveillance response. "And that only scratches the surface of its work," according to The Hill.11

AFBF supported the Fighting Hunger Incentive Act of 2014 (H.R. 4719; 113th Congress), a bill that would amend the Internal Revenue Code to permanently extend and expand certain expired provisions that provided an enhanced tax deduction for businesses that donated their food inventory to charitable organizations. AFBF argued that without the tax write-off, "it is cheaper in most cases for these types of businesses to throw their food away than it is to donate the food".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the American Farm Bureau Federation:

- The American Farm Bureau Federation Web site

- Farm Bureau Historical Highlights, 1919-1994

- Link to state Farm Bureaus

- History

- Personnel

- See also:

4-H Youth Organization

YouTube Video: 4-H Club: Healthy and Hands-on

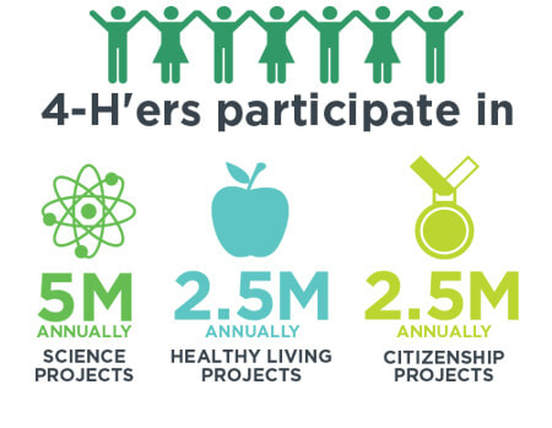

Pictured below: 4-H Youth Programs at a glance

4-H is a global network of youth organizations whose mission is "engaging youth to reach their fullest potential while advancing the field of youth development". Its name is a reference to the occurrence of the initial letter H four times in the organization's original motto ‘head, heart, hands, and health’ which was later incorporated into the fuller pledge officially adopted in 1927.

In the United States, the organization is administered by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

4-H Canada is an independent non-profit organization overseeing the operation of branches throughout Canada.

Throughout the world, 4-H organizations exist in over 50 countries; the organization and administration varies from country to country. Each of these programs operates independently but cooperatively through international exchanges, global education programs, and communications.

The 4-H name represents four personal development areas of focus for the organization: head, heart, hands, and health. As of 2016, the organization had nearly 6 million active participants and more than 25 million alumni.

The goal of 4-H is to develop citizenship, leadership, responsibility and life skills of youth through experiential learning programs and a positive youth development approach. Though typically thought of as an agriculturally focused organization as a result of its history, 4-H today focuses on citizenship, healthy living, science, engineering, and technology programs.

The 4-H motto is "To make the best better", while its slogan is "Learn by doing" (sometimes written as "Learn to do by doing").

Pledge:

The 4-H pledge is:

The original pledge was written by Otis E. Hall of Kansas in 1918. Some California 4-H clubs add either "As a true 4-H member" or "As a loyal 4-H member" at the beginning of the pledge. Minnesota and Maine 4-H clubs add "for my family" to the last line of the pledge.

Originally, the pledge ended in "and my country". In 1973, "and my world" was added.

It is a common practice to involve hand motions to accompany these spoken words. While reciting the first line of the pledge, the speaker will point to their head with both of their hands. As the speaker recites the second line, they will place their right hand over their heart, much like during the Pledge of Allegiance.

For the third line, the speaker will present their hands, palm side up, before them. For the fourth line, the speaker will motion to their body down their sides. And for the final line, the speaker will usually place their right hand out for club, left hand for community, bring them together for country, and then bring their hands upwards in a circle for world.

Emblem:

The official 4-H emblem is a green four-leaf clover with a white H on each leaf standing for Head, Heart, Hands, and Health. The stem of the clover always points to the right.

The idea of using the four-leaf clover as an emblem for the 4-H program is credited to Oscar Herman Benson (1875–1951) of Wright County Iowa. He awarded three-leaf and four-leaf clover pennants and pins for students' agricultural and domestic science exhibits at school fairs.

The 4-H name and emblem have U.S. federal protection, under federal code 18 U.S.C. 707. This federal protection makes it a mark unto and of itself with protection that supersedes the limited authorities of both a trademark and a copyright.

The Secretary of Agriculture is given responsibility and stewardship for the 4-H name and emblem, at the direct request of the U.S. Congress. These protections place the 4-H emblem in a unique category of protected emblems, along with the U.S. Presidential Seal, Red Cross, Smokey Bear and the Olympic rings.

Youth development research:

Through the program's tie to land-grant institutions of higher education, 4-H academic staff are responsible for advancing the field of youth development. Professional academic staff are committed to innovation, the creation of new knowledge, and the dissemination of new forms of program practice and research on topics like University of California's study of thriving in young people.

Youth development research is undertaken in a variety of forms including program evaluation, applied research, and introduction of new programs.

Volunteers:

Volunteering has deep roots in American society. Over half of the American people will volunteer in some capacity during a year's time. It is estimated that 44% of adults (over 83.9 million people) will volunteer within a year. This volunteerism is valued at over $239 billion per year. These volunteers come from all different age groups, educational levels, backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses.

Volunteer leaders play a major role in 4-H programs and are the heart and soul of 4-H. They perform a variety of roles, functions and tasks to coordinate the 4-H program at the county level and come from all walks of life, bringing varied and rich experiences to the 4-H program.

With over 540,000 volunteers nationally, these leaders play an essential role in the delivery of 4-H programs and provide learning opportunities to promote positive youth development.

Every year, volunteer leaders work to carry out 4-H youth development programs, project groups, camps, conferences, animal shows and many more 4-H related activities and events.

4-H volunteer leaders help youth to achieve greater self-confidence and self-responsibility, learn new skills and build relationships with others that will last a lifetime.

Volunteers serve in many diverse roles. Some are project leaders who teach youth skills and knowledge in an area of interest. Others are unit or community club leaders who organize clubs meetings and other programs.

Resource leaders are available to provide information and expertise. 4-H volunteers work under the direction of professional staff to plan and conduct activities and events, develop and maintain educational programs, and secure resources in support of the program.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about 4-H Youth Organizations:

In the United States, the organization is administered by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

4-H Canada is an independent non-profit organization overseeing the operation of branches throughout Canada.

Throughout the world, 4-H organizations exist in over 50 countries; the organization and administration varies from country to country. Each of these programs operates independently but cooperatively through international exchanges, global education programs, and communications.

The 4-H name represents four personal development areas of focus for the organization: head, heart, hands, and health. As of 2016, the organization had nearly 6 million active participants and more than 25 million alumni.

The goal of 4-H is to develop citizenship, leadership, responsibility and life skills of youth through experiential learning programs and a positive youth development approach. Though typically thought of as an agriculturally focused organization as a result of its history, 4-H today focuses on citizenship, healthy living, science, engineering, and technology programs.

The 4-H motto is "To make the best better", while its slogan is "Learn by doing" (sometimes written as "Learn to do by doing").

Pledge:

The 4-H pledge is:

- I pledge my head to clearer thinking,

- my heart to greater loyalty,

- my hands to larger service,

- and my health to better living,

- for my club, my community,

- my country, and my world.

The original pledge was written by Otis E. Hall of Kansas in 1918. Some California 4-H clubs add either "As a true 4-H member" or "As a loyal 4-H member" at the beginning of the pledge. Minnesota and Maine 4-H clubs add "for my family" to the last line of the pledge.

Originally, the pledge ended in "and my country". In 1973, "and my world" was added.

It is a common practice to involve hand motions to accompany these spoken words. While reciting the first line of the pledge, the speaker will point to their head with both of their hands. As the speaker recites the second line, they will place their right hand over their heart, much like during the Pledge of Allegiance.

For the third line, the speaker will present their hands, palm side up, before them. For the fourth line, the speaker will motion to their body down their sides. And for the final line, the speaker will usually place their right hand out for club, left hand for community, bring them together for country, and then bring their hands upwards in a circle for world.

Emblem:

The official 4-H emblem is a green four-leaf clover with a white H on each leaf standing for Head, Heart, Hands, and Health. The stem of the clover always points to the right.

The idea of using the four-leaf clover as an emblem for the 4-H program is credited to Oscar Herman Benson (1875–1951) of Wright County Iowa. He awarded three-leaf and four-leaf clover pennants and pins for students' agricultural and domestic science exhibits at school fairs.

The 4-H name and emblem have U.S. federal protection, under federal code 18 U.S.C. 707. This federal protection makes it a mark unto and of itself with protection that supersedes the limited authorities of both a trademark and a copyright.

The Secretary of Agriculture is given responsibility and stewardship for the 4-H name and emblem, at the direct request of the U.S. Congress. These protections place the 4-H emblem in a unique category of protected emblems, along with the U.S. Presidential Seal, Red Cross, Smokey Bear and the Olympic rings.

Youth development research:

Through the program's tie to land-grant institutions of higher education, 4-H academic staff are responsible for advancing the field of youth development. Professional academic staff are committed to innovation, the creation of new knowledge, and the dissemination of new forms of program practice and research on topics like University of California's study of thriving in young people.

Youth development research is undertaken in a variety of forms including program evaluation, applied research, and introduction of new programs.

Volunteers:

Volunteering has deep roots in American society. Over half of the American people will volunteer in some capacity during a year's time. It is estimated that 44% of adults (over 83.9 million people) will volunteer within a year. This volunteerism is valued at over $239 billion per year. These volunteers come from all different age groups, educational levels, backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses.

Volunteer leaders play a major role in 4-H programs and are the heart and soul of 4-H. They perform a variety of roles, functions and tasks to coordinate the 4-H program at the county level and come from all walks of life, bringing varied and rich experiences to the 4-H program.

With over 540,000 volunteers nationally, these leaders play an essential role in the delivery of 4-H programs and provide learning opportunities to promote positive youth development.

Every year, volunteer leaders work to carry out 4-H youth development programs, project groups, camps, conferences, animal shows and many more 4-H related activities and events.

4-H volunteer leaders help youth to achieve greater self-confidence and self-responsibility, learn new skills and build relationships with others that will last a lifetime.

Volunteers serve in many diverse roles. Some are project leaders who teach youth skills and knowledge in an area of interest. Others are unit or community club leaders who organize clubs meetings and other programs.

Resource leaders are available to provide information and expertise. 4-H volunteers work under the direction of professional staff to plan and conduct activities and events, develop and maintain educational programs, and secure resources in support of the program.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about 4-H Youth Organizations:

- 4-H Website Official website for more information about 4-H on all levels of the 4-H system

- History

- Additional programs

- Conferences

- Civil Rights issues

- Alumni

- See also:

Agronomy

YouTube Video: What is an Agronomist?

Pictured below: International Journal of Agronomy and Agricultural Research (IJAAR) publish high-quality original research papers together with review articles and short-communications.

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants for food, fuel, fiber, and land reclamation.

Agronomy has come to encompass work in the areas of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and soil science. It is the application of a combination of sciences like biology, chemistry, economics, ecology, earth science, and genetics.

Agronomists of today are involved with many issues, including producing food, creating healthier food, managing the environmental impact of agriculture, and extracting energy from plants.

Agronomists often specialize in areas such as crop rotation, irrigation and drainage, plant breeding, plant physiology, soil classification, soil fertility, weed control, and insect and pest control.

Plant Breeding:

Main article: Plant breeding

An agronomist field sampling a trial plot of flax.This area of agronomy involves selective breeding of plants to produce the best crops under various conditions.

Plant breeding has increased crop yields and has improved the nutritional value of numerous crops, including corn, soybeans, and wheat. It has also led to the development of new types of plants. For example, a hybrid grain called triticale was produced by crossbreeding rye and wheat. Triticale contains more usable protein than does either rye or wheat. Agronomy has also been instrumental in fruit and vegetable production research.

Biotechnology:

Agronomists use biotechnology to extend and expedite the development of desired characteristic. Biotechnology is often a lab activity requiring field testing of the new crop varieties that are developed.

In addition to increasing crop yields agronomic biotechnology is increasingly being applied for novel uses other than food. For example, oilseed is at present used mainly for margarine and other food oils, but it can be modified to produce fatty acids for detergents, substitute fuels and petrochemicals.

Soil Science:

Main article: Agricultural soil science

Agronomists study sustainable ways to make soils more productive and profitable throughout the world. They classify soils and analyze them to determine whether they contain nutrients vital to plant growth.

Common macronutrients analyzed include compounds of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. Soil is also assessed for several micronutrients, like zinc and boron. The percentage of organic matter, soil pH, and nutrient holding capacity (cation exchange capacity) are tested in a regional laboratory.

Agronomists will interpret these lab reports and make recommendations to balance soil nutrients for optimal plant growth.

Soil conservation

In addition, agronomists develop methods to preserve the soil and to decrease the effects of erosion by wind and water. For example, a technique called contour plowing may be used to prevent soil erosion and conserve rainfall.

Researchers in agronomy also seek ways to use the soil more effectively in solving other problems. Such problems include the disposal of human and animal manure, water pollution, and pesticide build-up in the soil. As well as looking after the soil for future generations to come, such as the burning of paddocks after crop production. As well as pasture [management] Techniques include no-tilling crops, planting of soil-binding grasses along contours on steep slopes, and contour drains of depths up to 1 metre.

Agroecology:

Agroecology is the management of agricultural systems with an emphasis on ecological and environmental perspectives. This area is closely associated with work in the areas of sustainable agriculture, organic farming (next), and alternative food systems and the development of alternative cropping systems.

Theoretical modeling:

Theoretical production ecology tries to quantitatively study the growth of crops. The plant is treated as a kind of biological factory, which processes light, carbon dioxide, water, and nutrients into harvestable products. The main parameters considered are temperature, sunlight, standing crop biomass, plant production distribution, and nutrient and water supply.

See also:

Agronomy has come to encompass work in the areas of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and soil science. It is the application of a combination of sciences like biology, chemistry, economics, ecology, earth science, and genetics.

Agronomists of today are involved with many issues, including producing food, creating healthier food, managing the environmental impact of agriculture, and extracting energy from plants.

Agronomists often specialize in areas such as crop rotation, irrigation and drainage, plant breeding, plant physiology, soil classification, soil fertility, weed control, and insect and pest control.

Plant Breeding:

Main article: Plant breeding

An agronomist field sampling a trial plot of flax.This area of agronomy involves selective breeding of plants to produce the best crops under various conditions.

Plant breeding has increased crop yields and has improved the nutritional value of numerous crops, including corn, soybeans, and wheat. It has also led to the development of new types of plants. For example, a hybrid grain called triticale was produced by crossbreeding rye and wheat. Triticale contains more usable protein than does either rye or wheat. Agronomy has also been instrumental in fruit and vegetable production research.

Biotechnology:

Agronomists use biotechnology to extend and expedite the development of desired characteristic. Biotechnology is often a lab activity requiring field testing of the new crop varieties that are developed.

In addition to increasing crop yields agronomic biotechnology is increasingly being applied for novel uses other than food. For example, oilseed is at present used mainly for margarine and other food oils, but it can be modified to produce fatty acids for detergents, substitute fuels and petrochemicals.

Soil Science:

Main article: Agricultural soil science

Agronomists study sustainable ways to make soils more productive and profitable throughout the world. They classify soils and analyze them to determine whether they contain nutrients vital to plant growth.

Common macronutrients analyzed include compounds of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. Soil is also assessed for several micronutrients, like zinc and boron. The percentage of organic matter, soil pH, and nutrient holding capacity (cation exchange capacity) are tested in a regional laboratory.

Agronomists will interpret these lab reports and make recommendations to balance soil nutrients for optimal plant growth.

Soil conservation

In addition, agronomists develop methods to preserve the soil and to decrease the effects of erosion by wind and water. For example, a technique called contour plowing may be used to prevent soil erosion and conserve rainfall.

Researchers in agronomy also seek ways to use the soil more effectively in solving other problems. Such problems include the disposal of human and animal manure, water pollution, and pesticide build-up in the soil. As well as looking after the soil for future generations to come, such as the burning of paddocks after crop production. As well as pasture [management] Techniques include no-tilling crops, planting of soil-binding grasses along contours on steep slopes, and contour drains of depths up to 1 metre.

Agroecology:

Agroecology is the management of agricultural systems with an emphasis on ecological and environmental perspectives. This area is closely associated with work in the areas of sustainable agriculture, organic farming (next), and alternative food systems and the development of alternative cropping systems.

Theoretical modeling:

Theoretical production ecology tries to quantitatively study the growth of crops. The plant is treated as a kind of biological factory, which processes light, carbon dioxide, water, and nutrients into harvestable products. The main parameters considered are temperature, sunlight, standing crop biomass, plant production distribution, and nutrient and water supply.

See also:

- The American Society of Agronomy (ASA)

- Crop Science Society of America (CSSA)

- Soil Science Society of America (SSSA)

- European Society for Agronomy

- The National Agricultural Library (NAL) – Comprehensive agricultural library.

- Information System for Agriculture and Food Research

- Agricultural engineering

- Agricultural policy

- Agroecology

- Agrology

- Agrophysics

- Food systems

- Green Revolution

- Vegetable farming

Organic Farming

YouTube Video: Is Organic Food Better for Your Health?

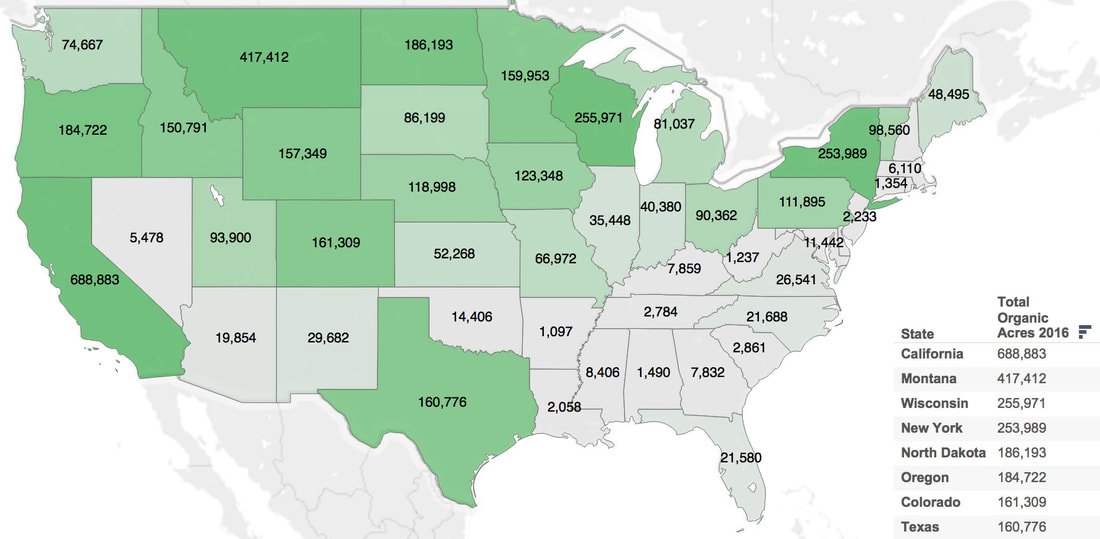

Pictured below: U.S. Organic Farmland Hits Record 4.1 Million Acres in 2016

Organic farming is an alternative agricultural system which originated early in the 20th century in reaction to rapidly changing farming practices.

Organic farming continues to be developed by various organic agriculture organizations today. It relies on fertilizers of organic origin such as compost manure, green manure, and bone meal and places emphasis on techniques such as crop rotation and companion planting.

Biological pest control, mixed cropping and the fostering of insect predators are encouraged. In general, organic standards are designed to allow the use of naturally occurring substances while prohibiting or strictly limiting synthetic substances. For instance, naturally occurring pesticides such as pyrethrin and rotenone are permitted, while synthetic fertilizers and pesticides are generally prohibited.

Synthetic substances that are allowed include, for example, copper sulfate, elemental sulfur and Ivermectin. Genetically modified organisms, nanomaterials, human sewage sludge, plant growth regulators, hormones, and antibiotic use in livestock husbandry are prohibited.

Reasons for advocation of organic farming include advantages in sustainability, openness, self-sufficiency, autonomy/independence, health, food security, and food safety.

Organic agricultural methods are internationally regulated and legally enforced by many nations, based in large part on the standards set by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), an international umbrella organization for organic farming organizations established in 1972.

Organic agriculture can be defined as an integrated farming system that strives for sustainability, the enhancement of soil fertility and biological diversity whilst, with rare exceptions, prohibiting synthetic pesticides, antibiotics, synthetic fertilizers, genetically modified organisms, and growth hormones.

Since 1990 the market for organic food and other products has grown rapidly, reaching $63 billion worldwide in 2012. This demand has driven a similar increase in organically managed farmland that grew from 2001 to 2011 at a compounding rate of 8.9% per annum.

As of 2016, approximately 57,800,000 hectares (143,000,000 acres) worldwide were farmed organically, representing approximately 1.2 percent of total world farmland.[14]

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Organic Farming:

Organic farming continues to be developed by various organic agriculture organizations today. It relies on fertilizers of organic origin such as compost manure, green manure, and bone meal and places emphasis on techniques such as crop rotation and companion planting.

Biological pest control, mixed cropping and the fostering of insect predators are encouraged. In general, organic standards are designed to allow the use of naturally occurring substances while prohibiting or strictly limiting synthetic substances. For instance, naturally occurring pesticides such as pyrethrin and rotenone are permitted, while synthetic fertilizers and pesticides are generally prohibited.

Synthetic substances that are allowed include, for example, copper sulfate, elemental sulfur and Ivermectin. Genetically modified organisms, nanomaterials, human sewage sludge, plant growth regulators, hormones, and antibiotic use in livestock husbandry are prohibited.

Reasons for advocation of organic farming include advantages in sustainability, openness, self-sufficiency, autonomy/independence, health, food security, and food safety.

Organic agricultural methods are internationally regulated and legally enforced by many nations, based in large part on the standards set by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), an international umbrella organization for organic farming organizations established in 1972.

Organic agriculture can be defined as an integrated farming system that strives for sustainability, the enhancement of soil fertility and biological diversity whilst, with rare exceptions, prohibiting synthetic pesticides, antibiotics, synthetic fertilizers, genetically modified organisms, and growth hormones.

Since 1990 the market for organic food and other products has grown rapidly, reaching $63 billion worldwide in 2012. This demand has driven a similar increase in organically managed farmland that grew from 2001 to 2011 at a compounding rate of 8.9% per annum.

As of 2016, approximately 57,800,000 hectares (143,000,000 acres) worldwide were farmed organically, representing approximately 1.2 percent of total world farmland.[14]

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Organic Farming:

- History

- Terminology

- Methods

- Standards including Composting

- Economics

- Disadvantages

- Regional support for organic farming

- See also:

- Organic Farming at Curlie

- Organic Eprints. A database of research in organic food and farming.

- Organic Agriculture. eOrganic Community of Practice with eXtension: America's Land Grant University System and Partners.

- Advance sowing

- Biodynamic agriculture

- Biointensive

- Biological pest control

- Certified Naturally Grown

- Companion planting

- Crop rotation

- Do Nothing Farming

- French intensive gardening

- Holistic management (agriculture)

- Integrated pest management

- List of organic food topics

- List of organic gardening and farming topics

- No-till farming

- Organic clothing

- Organic farming by country

- Organic Farming Digest

- Organic food

- Organic movement

- Permaculture

- SRI

- Organic food culture

- Zero Budget Farming

EcoAgriculture

YouTube Video: Windmills and Water Pumps for Livestock Water

YouTube Video: How can farming and renewable energy work together?

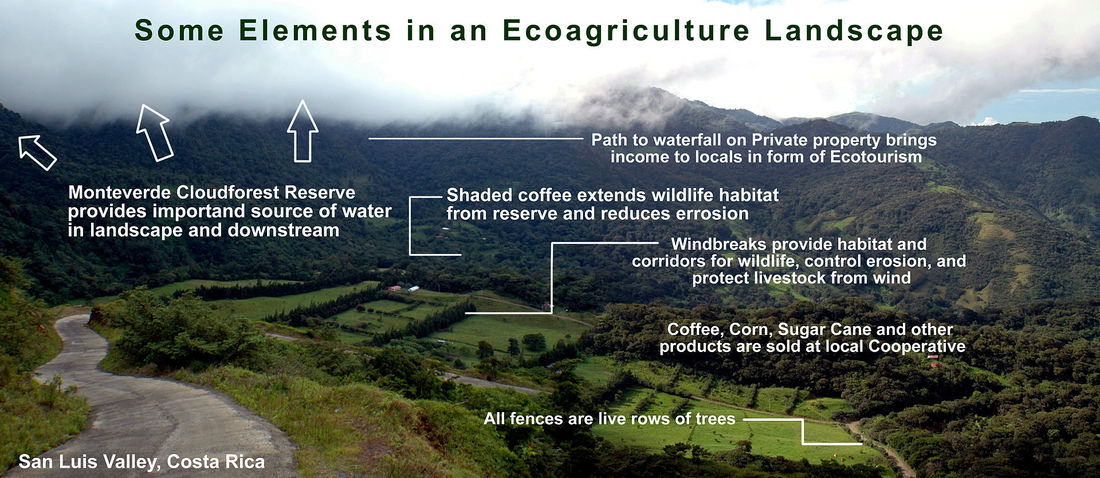

Pictured below: Elements in an eco-agriculture landscape (Courtesy of CC BY-SA 3.0)

Eco friendly agriculture describes landscapes that support both agricultural production and biodiversity conservation, working in harmony together to improve the livelihoods of rural communities.

While many rural communities have independently practiced eco-agriculture for thousands of years, over the past century many of these landscapes have given way to segregated land use patterns, with some areas employing intensive farming practices without regard to biodiversity impacts, and other areas fenced off completely for habitat or watershed protection.

A new eco-agriculture movement is now gaining momentum to unite land managers and other stakeholders from diverse environments to find compatible ways to conserve biodiversity while also enhancing agricultural production.

Approach and practitioners:

The term "eco-agriculture" was coined by Charles Walters, economist, author, editor, publisher, and founder of Acres Magazine in 1970 to unify under one umbrella the concepts of "ecological" and "economical" in the belief that unless agriculture was ecological it could not be economical. This belief became the motto of the magazine: "To be economical agriculture must be ecological."

Eco-agriculture is both a conservation strategy and a rural development strategy. Eco-agriculture recognizes agricultural producers and communities as key stewards of ecosystems and biodiversity and enables them to play those roles effectively.

Eco-agriculture applies an integrated ecosystem approach to agricultural landscapes to address all three pillars—conserving biodiversity, enhancing agricultural production, and improving livelihoods—drawing on diverse elements of production and conservation management systems.

Meeting the goals of eco-agriculture usually requires collaboration or coordination between diverse stakeholders who are collectively responsible for managing key components of a landscape.

Landscape scale:

Eco-agriculture uses the landscape as a unit of management. A landscape is a cluster of local ecosystems with a particular configuration of topography, vegetation, land use, and settlement.

The goals of eco-agriculture—to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem services, manage agricultural production sustainably, and contribute to improved livelihoods among rural people—cannot be achieved at just a farm or plot level, but are linked at the landscape level.

Therefore, to make an impact, all of the elements of a landscape as a whole must be considered; integrated landscape management is an approach that seeks to achieve this.

Defining a landscape depends on the local context. Landscapes may be defined or delimited by natural, historical, and/or cultural processes, activities or values. Landscapes can incorporate many different features, but all of the various features have some influence or effect on each other.

Landscapes can vary greatly in size, from the Congo Basin in west-central Africa where landscapes are often huge because there are vast stretches of apparently undifferentiated land, to western Europe where landscapes tend to be much smaller because of the wide diversity of topographies and land use activities occurring close to each other.

Importance of agriculture areas for biodiversity conservation:

Agriculture is the most dominant human influence on earth. Nearly one-third of the world’s land area is heavily influenced by cropland or planted pastures. An even greater area is being fallowed as part of an agricultural cycle or is in tree crops, livestock grazing systems, or production forestry.

In addition, most of the world’s 100,000+ protected areas contain significant amounts of agricultural land. And over half of the most species-rich areas in the world contain large human populations whose livelihoods depend on farming, forestry, herding, or fisheries.

Agriculture as it is often practiced today threatens wild plant and animal species and the natural ecosystem services upon which both humans and wildlife depend. Over 70% of the fresh water withdrawn by humans goes to irrigation for crops, causing a profound impact on the hydrological cycles of ecological systems.

Moreover, fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural waste threaten habitats and protected areas downstream. Land-clearing for agriculture also disrupts sources of food and shelter for wild biodiversity, and unsustainable fishing practices deplete freshwater and coastal fisheries.

Additionally, an increase in the planting and marketing of monoculture crops across the globe has decreased diversity in agricultural products, to the extent that many local varieties of fruits, vegetables, and grains have now become extinct. Given that demands on global agricultural production are increasing, it is imperative that the management of agricultural landscapes be improved to both increase productivity and enhance biodiversity conservation.

Wild biodiversity increasingly depends on agricultural producers to find ways to better protect habitats, and agriculture critically needs healthy and diverse ecosystems to sustain productivity.

Bridging conservation and agriculture:

Traditionally there has existed a divide between conservationists, who want to set land aside for the protection of wild biodiversity, and agriculturalists, who want to use land for production.

Because more than half of all plant and animal species exist principally outside protected areas –- mostly in agricultural landscapes –- there is a great need to close the gap between conservation efforts and agricultural production. For example, conservation of wetlands within agricultural landscapes is critical for wild bird populations. Such species require initiatives by and with farmers.

Ecoagriculture provides a bridge for these two communities to come together.

Farmers as ecosystem partners:

Farming communities play a vital role as managers of their ecosystems and biodiversity. As Ben Falk points out, they are often viewed as stewards. In his understanding, "Stewardship implies dominion, whereas partnership implies co[-]evolution; mutual respect; whole-archy, not hierarchy. A partner is sometimes a guide, always a facilitator, always a co[-]worker."

Since a farmer's dependence on their land and natural resources necessitates a conservation ethic, their farm productivity critically demands their assistance in delivering a range of ecosystem services.

Wild species often also play an important role in providing livestock fodder, fuel, veterinary medicines, soil nutrient supplements and construction materials to farmers, as well constituting an essential element of cultural, religious, and spiritual practices.

The dominance of agriculture in global land use requires that eco-agriculture approaches be fostered by rural producers and their communities on a globally significant scale. To do this, farmers need to be able to conserve biodiversity more consistently in ways that benefit their livelihoods.

Experiences from around the world suggest that there are a number of incentives to encourage and enable farmers and their communities to preserve or transition towards eco-agriculture landscapes:

Ecoagriculture land management practices:

Agricultural landscapes that aim to achieve the objectives of ecoagriculture –- enhanced biodiversity conservation, increased food production, and improved rural livelihoods –- should be managed in ways that protect and expand natural areas and improve wildlife habitats and ecosystem functions, in collaboration with local communities to insure their benefit.

Specific land management practices that may be incorporated include:

Role of traditional and local knowledge:

Many indigenous peoples and rural communities have developed, maintained, and adapted different types of ecoagriculture systems for centuries.

Local farmers, pastoralists, fishers, forest users, and other community members are the foundation of rural land stewardship. Their knowledge, traditions, land use practices, and resource-management institutions are essential to the development of viable ecoagriculture systems for their landscapes.

The mainstreaming of ecoagriculture approaches will be crucially dependent upon mobilizing local communities to become leaders in ecoagriculture, as teachers and as advocates for political and institutional change.

Communities facing similar challenges can share questions, ideas, and solutions with each other. Local communities also need effective processes for sharing their expertise with national policymakers and the international community and thus play a more central role in settinge coagriculture objectives in policy and program development.

Contribution of ecoagriculture to the Millennium Development Goals:

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), eight ambitious targets which range from halving extreme poverty to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS and providing universal primary education, were put forth by the United Nations in 2000, to be achieved by 2015.

Ecoagriculture strategies will be essential to achieving the MDGs, particularly for hunger and poverty, water and sanitation, and environmental sustainability.

The MDGs will not be reached without securing the ability of the rural poor to feed their families and gain income, while at the same time protecting the biodiversity and ecosystem services that sustain their livelihoods.

Of the estimated 800 million people who do not have access to sufficient food, half are smallholder farmers, one-fifth are rural landless, and one-tenth are principally dependent on rangelands, forests and fisheries. For most of them, reducing poverty and hunger will depend centrally on their ability to sustain and increase crop, livestock, forest, and fishery production.

A key opportunity for enhancing progress towards the MDGs is investment in locally-driven land management approaches –- such as ecoagriculture strategies –- that build upon synergies between rural livelihoods, environmental sustainability, and food security.

Related fields:

The values and/or principles of eco-agriculture have much in common with existing concepts, such as:

In fact, ‘ecoagriculture’ landscapes often feature many of these approaches. Ecoagriculture draws heavily on these and many other innovations in rural land use planning and management.

The landscape management framework defined by ecoagriculture has four particularly important characteristics:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about EcoAgriculture:

While many rural communities have independently practiced eco-agriculture for thousands of years, over the past century many of these landscapes have given way to segregated land use patterns, with some areas employing intensive farming practices without regard to biodiversity impacts, and other areas fenced off completely for habitat or watershed protection.

A new eco-agriculture movement is now gaining momentum to unite land managers and other stakeholders from diverse environments to find compatible ways to conserve biodiversity while also enhancing agricultural production.

Approach and practitioners:

The term "eco-agriculture" was coined by Charles Walters, economist, author, editor, publisher, and founder of Acres Magazine in 1970 to unify under one umbrella the concepts of "ecological" and "economical" in the belief that unless agriculture was ecological it could not be economical. This belief became the motto of the magazine: "To be economical agriculture must be ecological."

Eco-agriculture is both a conservation strategy and a rural development strategy. Eco-agriculture recognizes agricultural producers and communities as key stewards of ecosystems and biodiversity and enables them to play those roles effectively.

Eco-agriculture applies an integrated ecosystem approach to agricultural landscapes to address all three pillars—conserving biodiversity, enhancing agricultural production, and improving livelihoods—drawing on diverse elements of production and conservation management systems.

Meeting the goals of eco-agriculture usually requires collaboration or coordination between diverse stakeholders who are collectively responsible for managing key components of a landscape.

Landscape scale:

Eco-agriculture uses the landscape as a unit of management. A landscape is a cluster of local ecosystems with a particular configuration of topography, vegetation, land use, and settlement.

The goals of eco-agriculture—to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem services, manage agricultural production sustainably, and contribute to improved livelihoods among rural people—cannot be achieved at just a farm or plot level, but are linked at the landscape level.

Therefore, to make an impact, all of the elements of a landscape as a whole must be considered; integrated landscape management is an approach that seeks to achieve this.

Defining a landscape depends on the local context. Landscapes may be defined or delimited by natural, historical, and/or cultural processes, activities or values. Landscapes can incorporate many different features, but all of the various features have some influence or effect on each other.

Landscapes can vary greatly in size, from the Congo Basin in west-central Africa where landscapes are often huge because there are vast stretches of apparently undifferentiated land, to western Europe where landscapes tend to be much smaller because of the wide diversity of topographies and land use activities occurring close to each other.

Importance of agriculture areas for biodiversity conservation:

Agriculture is the most dominant human influence on earth. Nearly one-third of the world’s land area is heavily influenced by cropland or planted pastures. An even greater area is being fallowed as part of an agricultural cycle or is in tree crops, livestock grazing systems, or production forestry.

In addition, most of the world’s 100,000+ protected areas contain significant amounts of agricultural land. And over half of the most species-rich areas in the world contain large human populations whose livelihoods depend on farming, forestry, herding, or fisheries.

Agriculture as it is often practiced today threatens wild plant and animal species and the natural ecosystem services upon which both humans and wildlife depend. Over 70% of the fresh water withdrawn by humans goes to irrigation for crops, causing a profound impact on the hydrological cycles of ecological systems.

Moreover, fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural waste threaten habitats and protected areas downstream. Land-clearing for agriculture also disrupts sources of food and shelter for wild biodiversity, and unsustainable fishing practices deplete freshwater and coastal fisheries.

Additionally, an increase in the planting and marketing of monoculture crops across the globe has decreased diversity in agricultural products, to the extent that many local varieties of fruits, vegetables, and grains have now become extinct. Given that demands on global agricultural production are increasing, it is imperative that the management of agricultural landscapes be improved to both increase productivity and enhance biodiversity conservation.

Wild biodiversity increasingly depends on agricultural producers to find ways to better protect habitats, and agriculture critically needs healthy and diverse ecosystems to sustain productivity.

Bridging conservation and agriculture:

Traditionally there has existed a divide between conservationists, who want to set land aside for the protection of wild biodiversity, and agriculturalists, who want to use land for production.

Because more than half of all plant and animal species exist principally outside protected areas –- mostly in agricultural landscapes –- there is a great need to close the gap between conservation efforts and agricultural production. For example, conservation of wetlands within agricultural landscapes is critical for wild bird populations. Such species require initiatives by and with farmers.

Ecoagriculture provides a bridge for these two communities to come together.

Farmers as ecosystem partners:

Farming communities play a vital role as managers of their ecosystems and biodiversity. As Ben Falk points out, they are often viewed as stewards. In his understanding, "Stewardship implies dominion, whereas partnership implies co[-]evolution; mutual respect; whole-archy, not hierarchy. A partner is sometimes a guide, always a facilitator, always a co[-]worker."

Since a farmer's dependence on their land and natural resources necessitates a conservation ethic, their farm productivity critically demands their assistance in delivering a range of ecosystem services.

Wild species often also play an important role in providing livestock fodder, fuel, veterinary medicines, soil nutrient supplements and construction materials to farmers, as well constituting an essential element of cultural, religious, and spiritual practices.

The dominance of agriculture in global land use requires that eco-agriculture approaches be fostered by rural producers and their communities on a globally significant scale. To do this, farmers need to be able to conserve biodiversity more consistently in ways that benefit their livelihoods.

Experiences from around the world suggest that there are a number of incentives to encourage and enable farmers and their communities to preserve or transition towards eco-agriculture landscapes:

- Many management practices that improve ecosystem health also benefit farmers by reducing production costs, raising or stabilizing yields, or improving product quality. Intensive rotation grazing systems practiced in Europe, the United States, and Zimbabwe have been shown to reduce dairy production costs compared to stall-fed systems, while also reducing risks of land degradation and improving wildlife habitat.

- Farming communities are especially motivated to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services critical to their own livelihoods and cultural, spiritual, or aesthetic values. To protect their access to local water sources and medicinal plants, for example, farmers in western Kenya have mobilized to protect threatened forests in and near their communities. And in some agricultural landscapes in West Africa, 'sacred groves' are the principal remaining areas of native forest.

- Farmers are seeking new income opportunities from product markets that value supplies from biodiversity-friendly production systems. More than 80 eco-certification programs now provide opportunities for farmers to receive higher prices for products produced with environmentally friendly practices.

- Farmers can gain new income opportunities from payment for ecosystem services provided by non-farm beneficiaries of their ecological partnership. These opportunities include carbon emission offset payments for carbon sequestration in soils and trees and water quality protection, among others.

- Farmers are seeking ways to comply with the goals of environmental regulation, in ways that also maintain or improve their agricultural livelihoods. In the US, farmers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are incorporating perennial vegetative buffer strips around stream banks, which provide habitat niches for birds and wildlife, to both help meet water quality regulations and to diversify their output.

Ecoagriculture land management practices:

Agricultural landscapes that aim to achieve the objectives of ecoagriculture –- enhanced biodiversity conservation, increased food production, and improved rural livelihoods –- should be managed in ways that protect and expand natural areas and improve wildlife habitats and ecosystem functions, in collaboration with local communities to insure their benefit.

Specific land management practices that may be incorporated include: