Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Consumers

includes all of us who buy the products and services of the retail market, along with their regulation by the government and other consumer affairs organizations, e.g. the Better Business Bureau, to ensure fair trade business policies.

Consumers including the laws protecting them

YouTube Video: What To Do If You're A Victim of Identity Theft (The Federal Trade Commission)

Pictured: Consumer's Bill of Rights

Economics and marketing:

The consumer is the one who pays to consume goods and services produced. As such, consumers play a vital role in the economic system of a nation. Without consumer demand, producers would lack one of the key motivations to produce: to sell to consumers.

The consumer also forms part of the chain of distribution.

Recently in marketing instead of marketers generating broad demographic profiles and Fisio-graphic profiles of market segments, marketers have started to engage in personalized marketing, permission marketing, and mass customization.

Largely due the rise of the Internet, consumers are shifting more and more towards becoming "prosumers" – consumers that are also producers (often of information and media on the social web) or influence the products created (e.g. by customization, crowdfunding or publishing their preferences) or actively participate in the production process or use interactive products.

Law and politics:

The law primarily uses the notion of the consumer in relation to consumer protection laws, and the definition of consumer is often restricted to living persons (i.e. not corporations or businesses) and excludes commercial users.

A typical legal rationale for protecting the consumer is based on the notion of policing market failures and inefficiencies, such as inequalities of bargaining power between a consumer and a business. As of all potential voters are also consumers, consumer protection takes on a clear political significance.

Concern over the interests of consumers has also spawned activism, as well as incorporation of consumer education into school curricula. There are also various non-profit publications, such as Which?, Consumer Reports and Choice Magazine, dedicated to assist in consumer education and decision making.

Public reaction:

While use of the term consumer is widespread among governmental, business and media organisations, many individuals and groups find the label objectionable because it assigns a limited and passive role to their activities.

See also:

The consumer is the one who pays to consume goods and services produced. As such, consumers play a vital role in the economic system of a nation. Without consumer demand, producers would lack one of the key motivations to produce: to sell to consumers.

The consumer also forms part of the chain of distribution.

Recently in marketing instead of marketers generating broad demographic profiles and Fisio-graphic profiles of market segments, marketers have started to engage in personalized marketing, permission marketing, and mass customization.

Largely due the rise of the Internet, consumers are shifting more and more towards becoming "prosumers" – consumers that are also producers (often of information and media on the social web) or influence the products created (e.g. by customization, crowdfunding or publishing their preferences) or actively participate in the production process or use interactive products.

Law and politics:

The law primarily uses the notion of the consumer in relation to consumer protection laws, and the definition of consumer is often restricted to living persons (i.e. not corporations or businesses) and excludes commercial users.

A typical legal rationale for protecting the consumer is based on the notion of policing market failures and inefficiencies, such as inequalities of bargaining power between a consumer and a business. As of all potential voters are also consumers, consumer protection takes on a clear political significance.

Concern over the interests of consumers has also spawned activism, as well as incorporation of consumer education into school curricula. There are also various non-profit publications, such as Which?, Consumer Reports and Choice Magazine, dedicated to assist in consumer education and decision making.

Public reaction:

While use of the term consumer is widespread among governmental, business and media organisations, many individuals and groups find the label objectionable because it assigns a limited and passive role to their activities.

See also:

- Alpha consumer

- Consumer debt

- Consumer leverage ratio

- Consumer theory

- Consumerism

- Consumers' cooperative

- Consumption

- Coolhunting

- Mass customization

- Media consumption

- Mental health consumer

- Consumer reporting agency

- Consumer protection

- Consumer organization

- Consumer Direct

- National Consumer Agency (NCA)

- Informed consumer

- Perplexity consumer

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau of the United States, formed as a result of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010

YouTube Video: Barney Frank explains Dodd-Frank Act on Charlie Rose

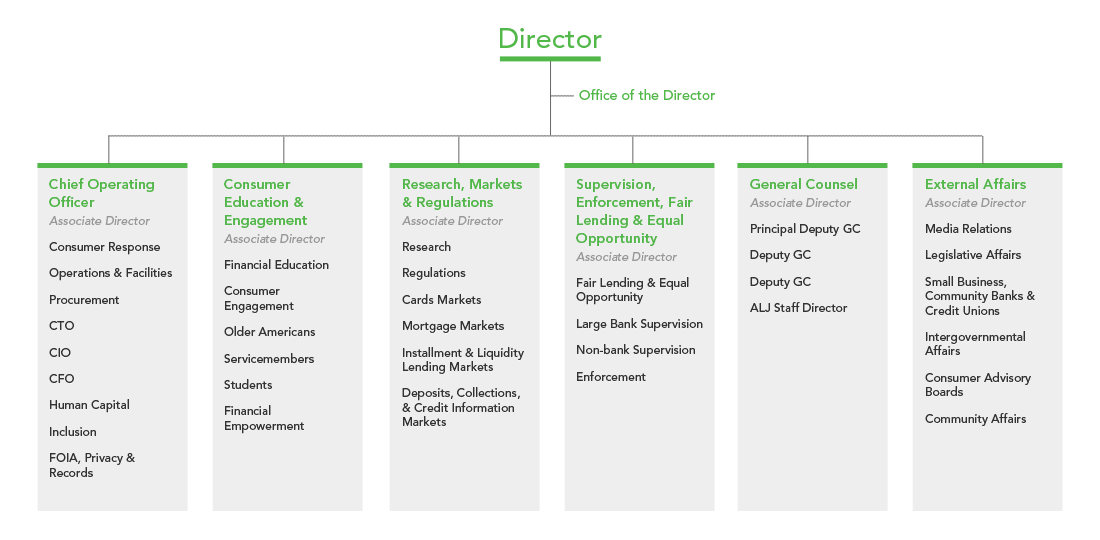

Pictured: Organizational Structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau created July, 2010 through the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Pub.L. 111–203, H.R. 4173; commonly referred to as Dodd–Frank) was signed into federal law by President Barack Obama on July 21, 2010. Passed as a response to the Great Recession, it brought the most significant changes to financial regulation in the United States since the regulatory reform that followed the Great Depression.

The act made changes in the American financial regulatory environment that affect all federal financial regulatory agencies and almost every part of the nation's financial services industry.

The law was initially proposed by the Obama administration in June 2009, when the White House sent a series of proposed bills to Congress. A version of the legislation was introduced in the House in July 2009. On December 2, 2009, revised versions were introduced in the House of Representatives by the then Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank, and in the Senate Banking Committee by former Chairman Chris Dodd. Due to Dodd and Frank's involvement with the bill, the conference committee that reported on June 25, 2010 voted to name the bill after them.

As with other major financial reforms, a variety of critics have attacked the law, with some arguing it was insufficient to prevent another financial crisis (or more bailouts) and others contending it went too far and unduly restricted financial institutions. President-Elect Donald Trump's transition team has vowed to dismantle the Dodd–Frank act.

Click here for further amplification on the Dodd-Frank Act.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau:

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is an agency of the United States government responsible for consumer protection in the financial sector. CFPB jurisdiction includes

The CFPB's creation was authorized by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, whose passage in 2010 was a legislative response to the financial crisis of 2007–08 and the subsequent Great Recession.

The CFPB was initially established as an independent agency but it effectively became an executive agency after a federal appeals court found that the President of the United States' power to remove the CFPB Director had been unconstitutionally limited.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

The act made changes in the American financial regulatory environment that affect all federal financial regulatory agencies and almost every part of the nation's financial services industry.

The law was initially proposed by the Obama administration in June 2009, when the White House sent a series of proposed bills to Congress. A version of the legislation was introduced in the House in July 2009. On December 2, 2009, revised versions were introduced in the House of Representatives by the then Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank, and in the Senate Banking Committee by former Chairman Chris Dodd. Due to Dodd and Frank's involvement with the bill, the conference committee that reported on June 25, 2010 voted to name the bill after them.

As with other major financial reforms, a variety of critics have attacked the law, with some arguing it was insufficient to prevent another financial crisis (or more bailouts) and others contending it went too far and unduly restricted financial institutions. President-Elect Donald Trump's transition team has vowed to dismantle the Dodd–Frank act.

Click here for further amplification on the Dodd-Frank Act.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau:

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is an agency of the United States government responsible for consumer protection in the financial sector. CFPB jurisdiction includes

- banks,

- credit unions,

- securities firms,

- payday lenders,

- mortgage-servicing operations,

- foreclosure relief services,

- debt collectors

- and other financial companies operating in the United States.

The CFPB's creation was authorized by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, whose passage in 2010 was a legislative response to the financial crisis of 2007–08 and the subsequent Great Recession.

The CFPB was initially established as an independent agency but it effectively became an executive agency after a federal appeals court found that the President of the United States' power to remove the CFPB Director had been unconstitutionally limited.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

Online Ad Tracking: why you see ads online from businesses you just visited

YouTube Video: TED Presents "Tracking the Tracker" by Gary Kovacs

Pictured: Facebook’s new ads will track which stores you visit

Courtesy of Federal Trade Commission (June, 2016)

Have you ever wondered why some online ads you see are targeted to your tastes and interests? Or how websites remember your preferences from visit-to-visit or device-to-device? The answer may be in the “cookies” – or in other online tracking methods like device fingerprinting and cross-device tracking.

Here are answers to some commonly asked questions about online tracking — how it works and how you can control it.

Understanding Cookies

What is a cookie?A cookie is information saved by your web browser, the software program you use to visit the web. When you visit a website, the site might store a cookie so it can recognize your device in the future. Later if you return to that site, it can read that cookie to remember you from your last visit. By keeping track of you over time, cookies can be used to customize your browsing experience, or to deliver ads targeted to you.

Who places cookies on the web?

First-party cookies are placed by the site that you visit. They can make your experience on the web more efficient. For example, they help sites remember:

Third-party cookies are placed by someone other than the site you are on. For example, the website may partner with an advertising network to deliver some of the ads you see. Or they may partner with an analytics company to help understand how people use their site. These “third party” companies also may place cookies in your browser to monitor your behavior over time.

Over time, these companies may develop a detailed history of the types of sites you frequent, and they may use this information to deliver ads tailored to your interests. For example, if an advertising company notices that you read a lot of articles about running, it may show you ads about running shoes – even on an unrelated site you’re visiting for the first time.

Understanding Other Online Tracking: What are Flash cookies?

A Flash cookie is a small file stored on your computer by a website that uses Adobe’s Flash player technology. Flash cookies use Adobe’s Flash player to store information about your online browsing activities. Flash cookies can be used to replace cookies used for tracking and advertising, because they also can store your settings and preferences. Similarly, companies can place unique HTML5 cookies within a browser’s local storage to identify a user over time. When you delete or clear cookies from your browser, you will not necessarily delete the Flash cookies stored on your computer.

What is device fingerprinting?

Device fingerprinting can track devices over time, based on your browser’s configurations and settings. Because each browser is unique, device fingerprinting can identify your device, without using cookies. Since device fingerprinting uses the characteristics of your browser configuration to track you, deleting cookies won’t help.

Device fingerprinting technologies are evolving and can be used to track you on all kinds of internet-connected devices that have browsers, such as smart phones, tablets, laptop and desktop computers.

How does tracking in mobile apps occur?

When you access mobile applications, companies don’t have access to traditional browser cookies to track you over time. Instead, third party advertising and analytics companies use device identifiers — such as Apple iOS’s Identifiers for Advertisers (“IDFA”) and Google Android’s Advertising ID — to monitor the different applications used on a particular device.

Does tracking of other “smart devices” occur?

Yes. More and more, consumer devices, in addition to phones, are capable of being connected online. For example, smart entertainment systems often provide new ways for you to watch TV shows and movies, and also may use technology to monitor what you watch. Look to the settings on your devices to investigate whether you can reset identifiers on the devices or use web interfaces on another device to limit ad tracking.

Controlling Online Tracking: How can I control cookies?

Various browsers have different ways to let you delete cookies or limit the kinds of cookies that can be placed on your computer. When you choose a browser, consider which suits your privacy preferences best.

To check out the settings in a browser, use the ‘Help’ tab or look under ‘Tools’ for settings like ‘Options’ or ‘Privacy.’ From there, you may be able to delete cookies, or control when they can be placed. Some browsers allow add-on software tools to block, delete, or control cookies. And security software often includes options to make cookie control easier. If you delete cookies, companies may not be able to associate you with your past browsing activity. However, they may be able to track you in the future with a new cookie.

If you block cookies entirely, you may limit your browsing experience. For example, you may need to enter information repeatedly, or you might not get personalized content that is meaningful to you. Most browsers’ settings will allow you to block third-party cookies without also disabling first-party cookies.

How can I control Flash cookies and device fingerprinting?

The latest versions of Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft Internet Explorer let you control or delete Flash cookies through the browser’s settings. If you use an older version of one of these browsers, upgrade to the most recent version, and set it to update automatically.

If you use a browser that doesn’t let you delete Flash cookies, look at Adobe’s Website Storage Settings panel. There, you can view and delete Flash cookies, and control whether you’ll allow them on your computer.

Like regular cookies, deleting Flash cookies gets rid of the ones on your computer at that moment. Flash cookies can be placed on your computer the next time you visit a website or view an ad unless you block Flash cookies altogether.

How can I control tracking in or across mobile apps?

You can reset the identifiers on your device in the device settings. iOS users can do this by following Settings > Privacy > Advertising > Reset Advertising Identifier. For Android, the path is Google settings > Ads > Reset advertising ID. This control works much like deleting cookies in a browser — the device is harder to associate with past activity, but tracking can start anew using the new advertising identifier.

You also can limit the use of identifiers for ad targeting on your devices. If you turn on this setting, apps are not permitted to use the advertising identifier to serve consumers targeted ads.

For iOS, the controls are available through Settings > Privacy > Advertising > Limit Ad Tracking.

For Android, Google Settings > Ads > Opt Out of Interest-Based Ads.

Although this tool will limit the use of tracking data for targeting ads, companies may still be able to monitor your app usage for other purposes, such as research, measurement, and fraud prevention.

Mobile browsers work much like traditional web browsers, and the tracking technologies and user controls are much the same as for ordinary web browsers, described above.

Mobile applications also may collect your geolocation to share with advertising companies. The latest versions of iOS and Android allow you to limit which particular applications can access your location information.

What is “private browsing”?

Many browsers offer private browsing settings that are meant to let you keep your web activities hidden from other people who use the same computer. With private browsing turned on, your browser won’t retain cookies, your browsing history, search records, or the files you downloaded. Privacy modes aren’t uniform, though; it’s a good idea to check your browser to see what types of data it stores.

But note that cookies used during the private browsing session still can communicate information about your browsing behavior to third parties. So, private browsing may not be effective in stopping third parties from using techniques such as fingerprinting to track your web activity.

What are “opt-out” cookies?

Some websites and advertising networks allow you to set cookies that tell them not to use information about what sites you visit to target ads to you.

For example, the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) and the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA) offer tools for opting out of targeted advertising — often by placing opt-out cookies. If you delete all cookies, you’ll also delete the cookies that indicate your preference to opt out of targeted ads.

Cookies are used for many purposes — for example, to limit the number of times you’re shown a particular ad. So even if you opt out of targeted advertising, a company may still use cookies for other purposes.

What is “Do Not Track”?

Do Not Track is a setting in most internet browsers that allows you to express your preference not to be tracked across the web. Turning on Do Not Track through your web browser sends a signal to every website you visit that you don’t want to be tracked from site to site. Companies then know your preference.

If they have committed to respect your Do Not Track preference, they are legally required to do so. However, most tracking companies today have not committed to honoring users’ Do Not Track preferences.

Can I block online tracking?

Consumers can learn about tracker-blocking browser plugins which block the flow of information from a computer to tracking companies and allow consumers to block ads. They prevent companies from using cookies or fingerprinting to track your internet behavior.

To find tracker-blocking plugins, type “tracker blocker” in your search engine. Then, compare features to decide which tracker blocker is best for you. For example, some of them block tracking by default, while others require you to customize when you’ll block tracking.

Remember that websites that rely on third party tracking companies for measurement or advertising revenue may prevent you from using their site if you have blocking software installed. However, you can still open those sites in a separate browser that doesn’t have blocking enabled, or you can disable blocking on those sites.

Tagged with: computer security, cookies, Do Not Track, personal information, privacy

You Might Also Like

Have you ever wondered why some online ads you see are targeted to your tastes and interests? Or how websites remember your preferences from visit-to-visit or device-to-device? The answer may be in the “cookies” – or in other online tracking methods like device fingerprinting and cross-device tracking.

Here are answers to some commonly asked questions about online tracking — how it works and how you can control it.

Understanding Cookies

What is a cookie?A cookie is information saved by your web browser, the software program you use to visit the web. When you visit a website, the site might store a cookie so it can recognize your device in the future. Later if you return to that site, it can read that cookie to remember you from your last visit. By keeping track of you over time, cookies can be used to customize your browsing experience, or to deliver ads targeted to you.

Who places cookies on the web?

First-party cookies are placed by the site that you visit. They can make your experience on the web more efficient. For example, they help sites remember:

- items in your shopping cart

- your log-in name

- your preferences, like always showing the weather in your home town

- your high game scores.

Third-party cookies are placed by someone other than the site you are on. For example, the website may partner with an advertising network to deliver some of the ads you see. Or they may partner with an analytics company to help understand how people use their site. These “third party” companies also may place cookies in your browser to monitor your behavior over time.

Over time, these companies may develop a detailed history of the types of sites you frequent, and they may use this information to deliver ads tailored to your interests. For example, if an advertising company notices that you read a lot of articles about running, it may show you ads about running shoes – even on an unrelated site you’re visiting for the first time.

Understanding Other Online Tracking: What are Flash cookies?

A Flash cookie is a small file stored on your computer by a website that uses Adobe’s Flash player technology. Flash cookies use Adobe’s Flash player to store information about your online browsing activities. Flash cookies can be used to replace cookies used for tracking and advertising, because they also can store your settings and preferences. Similarly, companies can place unique HTML5 cookies within a browser’s local storage to identify a user over time. When you delete or clear cookies from your browser, you will not necessarily delete the Flash cookies stored on your computer.

What is device fingerprinting?

Device fingerprinting can track devices over time, based on your browser’s configurations and settings. Because each browser is unique, device fingerprinting can identify your device, without using cookies. Since device fingerprinting uses the characteristics of your browser configuration to track you, deleting cookies won’t help.

Device fingerprinting technologies are evolving and can be used to track you on all kinds of internet-connected devices that have browsers, such as smart phones, tablets, laptop and desktop computers.

How does tracking in mobile apps occur?

When you access mobile applications, companies don’t have access to traditional browser cookies to track you over time. Instead, third party advertising and analytics companies use device identifiers — such as Apple iOS’s Identifiers for Advertisers (“IDFA”) and Google Android’s Advertising ID — to monitor the different applications used on a particular device.

Does tracking of other “smart devices” occur?

Yes. More and more, consumer devices, in addition to phones, are capable of being connected online. For example, smart entertainment systems often provide new ways for you to watch TV shows and movies, and also may use technology to monitor what you watch. Look to the settings on your devices to investigate whether you can reset identifiers on the devices or use web interfaces on another device to limit ad tracking.

Controlling Online Tracking: How can I control cookies?

Various browsers have different ways to let you delete cookies or limit the kinds of cookies that can be placed on your computer. When you choose a browser, consider which suits your privacy preferences best.

To check out the settings in a browser, use the ‘Help’ tab or look under ‘Tools’ for settings like ‘Options’ or ‘Privacy.’ From there, you may be able to delete cookies, or control when they can be placed. Some browsers allow add-on software tools to block, delete, or control cookies. And security software often includes options to make cookie control easier. If you delete cookies, companies may not be able to associate you with your past browsing activity. However, they may be able to track you in the future with a new cookie.

If you block cookies entirely, you may limit your browsing experience. For example, you may need to enter information repeatedly, or you might not get personalized content that is meaningful to you. Most browsers’ settings will allow you to block third-party cookies without also disabling first-party cookies.

How can I control Flash cookies and device fingerprinting?

The latest versions of Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft Internet Explorer let you control or delete Flash cookies through the browser’s settings. If you use an older version of one of these browsers, upgrade to the most recent version, and set it to update automatically.

If you use a browser that doesn’t let you delete Flash cookies, look at Adobe’s Website Storage Settings panel. There, you can view and delete Flash cookies, and control whether you’ll allow them on your computer.

Like regular cookies, deleting Flash cookies gets rid of the ones on your computer at that moment. Flash cookies can be placed on your computer the next time you visit a website or view an ad unless you block Flash cookies altogether.

How can I control tracking in or across mobile apps?

You can reset the identifiers on your device in the device settings. iOS users can do this by following Settings > Privacy > Advertising > Reset Advertising Identifier. For Android, the path is Google settings > Ads > Reset advertising ID. This control works much like deleting cookies in a browser — the device is harder to associate with past activity, but tracking can start anew using the new advertising identifier.

You also can limit the use of identifiers for ad targeting on your devices. If you turn on this setting, apps are not permitted to use the advertising identifier to serve consumers targeted ads.

For iOS, the controls are available through Settings > Privacy > Advertising > Limit Ad Tracking.

For Android, Google Settings > Ads > Opt Out of Interest-Based Ads.

Although this tool will limit the use of tracking data for targeting ads, companies may still be able to monitor your app usage for other purposes, such as research, measurement, and fraud prevention.

Mobile browsers work much like traditional web browsers, and the tracking technologies and user controls are much the same as for ordinary web browsers, described above.

Mobile applications also may collect your geolocation to share with advertising companies. The latest versions of iOS and Android allow you to limit which particular applications can access your location information.

What is “private browsing”?

Many browsers offer private browsing settings that are meant to let you keep your web activities hidden from other people who use the same computer. With private browsing turned on, your browser won’t retain cookies, your browsing history, search records, or the files you downloaded. Privacy modes aren’t uniform, though; it’s a good idea to check your browser to see what types of data it stores.

But note that cookies used during the private browsing session still can communicate information about your browsing behavior to third parties. So, private browsing may not be effective in stopping third parties from using techniques such as fingerprinting to track your web activity.

What are “opt-out” cookies?

Some websites and advertising networks allow you to set cookies that tell them not to use information about what sites you visit to target ads to you.

For example, the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) and the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA) offer tools for opting out of targeted advertising — often by placing opt-out cookies. If you delete all cookies, you’ll also delete the cookies that indicate your preference to opt out of targeted ads.

Cookies are used for many purposes — for example, to limit the number of times you’re shown a particular ad. So even if you opt out of targeted advertising, a company may still use cookies for other purposes.

What is “Do Not Track”?

Do Not Track is a setting in most internet browsers that allows you to express your preference not to be tracked across the web. Turning on Do Not Track through your web browser sends a signal to every website you visit that you don’t want to be tracked from site to site. Companies then know your preference.

If they have committed to respect your Do Not Track preference, they are legally required to do so. However, most tracking companies today have not committed to honoring users’ Do Not Track preferences.

Can I block online tracking?

Consumers can learn about tracker-blocking browser plugins which block the flow of information from a computer to tracking companies and allow consumers to block ads. They prevent companies from using cookies or fingerprinting to track your internet behavior.

To find tracker-blocking plugins, type “tracker blocker” in your search engine. Then, compare features to decide which tracker blocker is best for you. For example, some of them block tracking by default, while others require you to customize when you’ll block tracking.

Remember that websites that rely on third party tracking companies for measurement or advertising revenue may prevent you from using their site if you have blocking software installed. However, you can still open those sites in a separate browser that doesn’t have blocking enabled, or you can disable blocking on those sites.

Tagged with: computer security, cookies, Do Not Track, personal information, privacy

You Might Also Like

Data Mining vs. Right to Privacy*

* Article in Time Magazine, July 31, 2012 issue

YouTube Video: What is Data Mining?

Pictured: The process of data mining: for additional information, click here

Excerpt from Time Magazine, July 31, 2012 about the risks caused by data mining:

“Big Brother is watching you.” That’s a line from the dystopian classic 1984, but it’s also far closer to reality than most Americans realize. No, there’s not some totalitarian government spy in a trench coat following you, but you are being watched — not by a dictator, but by a handful of companies that make big bucks aggregating tiny scraps of information about you and putting the puzzle pieces together to build your digital profile. Eight lawmakers are demanding that these companies crack open their vaults so Congress can see what they’re compiling about us and what they’re doing with it.

Right now, this multibillion-dollar industry is largely unregulated. A New York Times article earlier this year about a data-mining company prompted the two co-chairs of the Bipartisan Congressional Privacy Caucus and six other Congress members to send a letter to nine companies that collect personal data.

They’ve asked these corporations where they get their data, how they slice and dice it, and to whom they sell and share it.

“By combining data from numerous offline and online sources, data brokers have developed hidden dossiers on almost every U.S. consumer,” the letter says. “This large scale aggregation of the personal information of hundreds of millions of American citizens raises a number of serious privacy concerns.”...."

Data mining is the computational process of discovering patterns in large data sets involving methods at the intersection of artificial intelligence, machine learning, statistics, and database systems.

It is an interdisciplinary subfield of computer science. The overall goal of the data mining process is to extract information from a data set and transform it into an understandable structure for further use.

Aside from the raw analysis step, it involves database and data management aspects, data pre-processing, model and inference considerations, interest metrics, complexity considerations, post-processing of discovered structures, visualization, and online updating. Data mining is the analysis step of the "knowledge discovery in databases" process, or KDD.

The term is a misnomer, because the goal is the extraction of patterns and knowledge from large amounts of data, not the extraction (mining) of data itself. It also is a buzzword and is frequently applied to any form of large-scale data or information processing (collection, extraction, warehousing, analysis, and statistics) as well as any application of computer decision support system, including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and business intelligence.

The book Data mining: Practical machine learning tools and techniques with Java (which covers mostly machine learning material) was originally to be named just Practical machine learning, and the term data mining was only added for marketing reasons.

Often the more general terms (large scale) data analysis and analytics – or, when referring to actual methods, artificial intelligence and machine learning – are more appropriate.

The actual data mining task is the automatic or semi-automatic analysis of large quantities of data to extract previously unknown, interesting patterns such as groups of data records (cluster analysis), unusual records (anomaly detection), and dependencies (association rule mining, sequential pattern mining).

This usually involves using database techniques such as spatial indices. These patterns can then be seen as a kind of summary of the input data, and may be used in further analysis or, for example, in machine learning and predictive analytics.

For example, the data mining step might identify multiple groups in the data, which can then be used to obtain more accurate prediction results by a decision support system. Neither the data collection, data preparation, nor result interpretation and reporting is part of the data mining step, but do belong to the overall KDD process as additional steps.

The related terms data dredging, data fishing, and data snooping refer to the use of data mining methods to sample parts of a larger population data set that are (or may be) too small for reliable statistical inferences to be made about the validity of any patterns discovered. These methods can, however, be used in creating new hypotheses to test against the larger data populations.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Data Mining:

“Big Brother is watching you.” That’s a line from the dystopian classic 1984, but it’s also far closer to reality than most Americans realize. No, there’s not some totalitarian government spy in a trench coat following you, but you are being watched — not by a dictator, but by a handful of companies that make big bucks aggregating tiny scraps of information about you and putting the puzzle pieces together to build your digital profile. Eight lawmakers are demanding that these companies crack open their vaults so Congress can see what they’re compiling about us and what they’re doing with it.

Right now, this multibillion-dollar industry is largely unregulated. A New York Times article earlier this year about a data-mining company prompted the two co-chairs of the Bipartisan Congressional Privacy Caucus and six other Congress members to send a letter to nine companies that collect personal data.

They’ve asked these corporations where they get their data, how they slice and dice it, and to whom they sell and share it.

“By combining data from numerous offline and online sources, data brokers have developed hidden dossiers on almost every U.S. consumer,” the letter says. “This large scale aggregation of the personal information of hundreds of millions of American citizens raises a number of serious privacy concerns.”...."

Data mining is the computational process of discovering patterns in large data sets involving methods at the intersection of artificial intelligence, machine learning, statistics, and database systems.

It is an interdisciplinary subfield of computer science. The overall goal of the data mining process is to extract information from a data set and transform it into an understandable structure for further use.

Aside from the raw analysis step, it involves database and data management aspects, data pre-processing, model and inference considerations, interest metrics, complexity considerations, post-processing of discovered structures, visualization, and online updating. Data mining is the analysis step of the "knowledge discovery in databases" process, or KDD.

The term is a misnomer, because the goal is the extraction of patterns and knowledge from large amounts of data, not the extraction (mining) of data itself. It also is a buzzword and is frequently applied to any form of large-scale data or information processing (collection, extraction, warehousing, analysis, and statistics) as well as any application of computer decision support system, including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and business intelligence.

The book Data mining: Practical machine learning tools and techniques with Java (which covers mostly machine learning material) was originally to be named just Practical machine learning, and the term data mining was only added for marketing reasons.

Often the more general terms (large scale) data analysis and analytics – or, when referring to actual methods, artificial intelligence and machine learning – are more appropriate.

The actual data mining task is the automatic or semi-automatic analysis of large quantities of data to extract previously unknown, interesting patterns such as groups of data records (cluster analysis), unusual records (anomaly detection), and dependencies (association rule mining, sequential pattern mining).

This usually involves using database techniques such as spatial indices. These patterns can then be seen as a kind of summary of the input data, and may be used in further analysis or, for example, in machine learning and predictive analytics.

For example, the data mining step might identify multiple groups in the data, which can then be used to obtain more accurate prediction results by a decision support system. Neither the data collection, data preparation, nor result interpretation and reporting is part of the data mining step, but do belong to the overall KDD process as additional steps.

The related terms data dredging, data fishing, and data snooping refer to the use of data mining methods to sample parts of a larger population data set that are (or may be) too small for reliable statistical inferences to be made about the validity of any patterns discovered. These methods can, however, be used in creating new hypotheses to test against the larger data populations.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Data Mining:

- Etymology

- Background

- Process

- Research

- Standards

- Notable uses

- Privacy concerns and ethics

- Copyright Law

- Software

- See also:

- Methods:

- Agent mining

- Anomaly/outlier/change detection

- Association rule learning

- Bayesian networks

- Classification

- Cluster analysis

- Decision trees

- Ensemble learning

- Factor analysis

- Genetic algorithms

- Intention mining

- Learning classifier system

- Multilinear subspace learning

- Neural networks

- Regression analysis

- Sequence mining

- Structured data analysis

- Support vector machines

- Text mining

- Time series analysis

- Application domains

- Application examples (Main article: Examples of data mining)

- Related topics: Data mining is about analyzing data; for information about extracting information out of data, see:

- Methods:

Examples of Data Mining

YouTube Video: Microsoft Data Mining Demo -- Fill from Example

Pictured: Microsoft Data Mining Demo -- Fill from Example with SQL Server 2008 and Excel 2007

Data mining has been used in many applications. Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for notable examples of usage:

- Games

- Business

- Science and engineering

- Human rights

- Medical data mining

- Spatial data mining

- Temporal data mining

- Sensor data mining

- Visual data mining

- Music data mining

- Surveillance

- Pattern mining

- Subject-based data mining

- Knowledge grid

[Your Web Host: Certainly, we are learning that the Internet is not a blessing for all. Below we take on the topic of what the Internet giants like Amazon.com are doing to your neighborhood malls and retailer "brick and mortar" chains and franchises, INCLUDING JOB LOSSES! It is not pretty!]

'Retail Apocalypse’ Is Really Just Beginning by Bloomberg News and What is "Retail Apocalypse"? (by Wikipedia)

YouTube Video: Top 10 Businesses Killed by the Internet by WatchMojo

YouTube Video: Macy's, Sears and Kmart Closing Stores - Online Sales Killing Brick-and-Mortars?

YouTube Video: "Click on PLAY ALL" to view Dead Mall Series

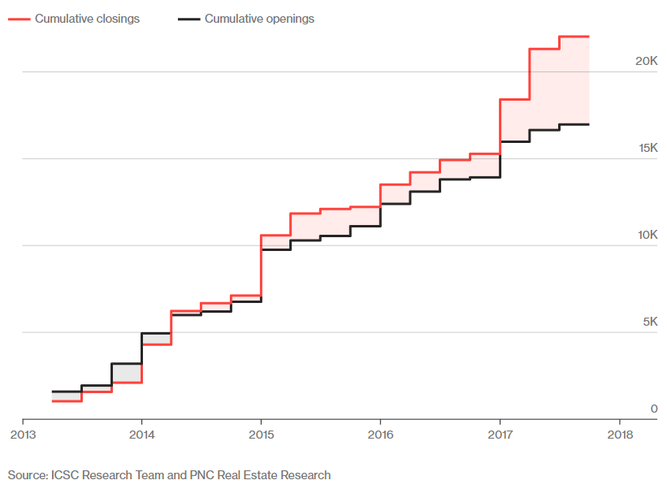

Pictured below: Impact of Internet on Retailers: Graphic of Announced store cumulative openings and closings (Excluding grocery stores and restaurants) (courtesy of Bloomberg News)

By Bloomberg News: The so-called retail apocalypse has become so ingrained in the U.S. that it now has the distinction of its own Wikipedia entry. (see below for "Retail Apocalypse")

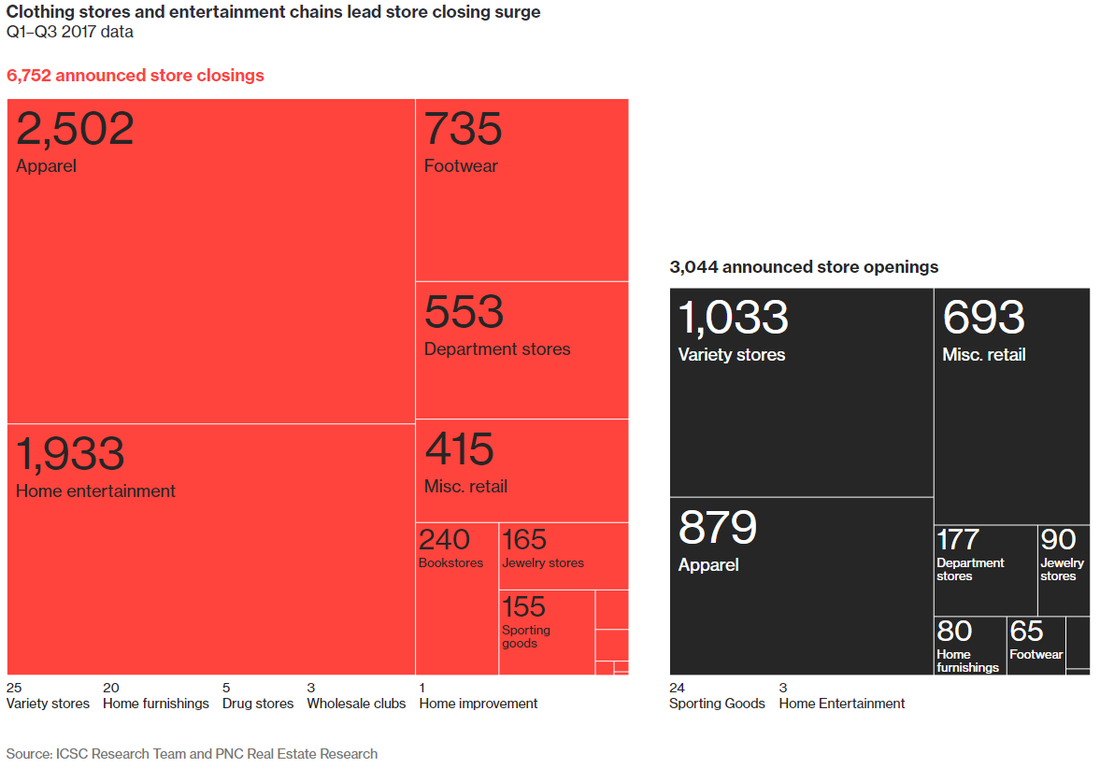

The industry’s response to that kind of doomsday description has included blaming the media for hyping the troubles of a few well-known chains as proof of a systemic meltdown. There is some truth to that. In the U.S., retailers announced more than 3,000 store openings in the first three quarters of this year.

But chains also said 6,800 would close. And this comes when there’s sky-high consumer confidence, unemployment is historically low and the U.S. economy keeps growing. Those are normally all ingredients for a retail boom, yet more chains are filing for bankruptcy and rated distressed than during the financial crisis. That’s caused an increase in the number of delinquent loan payments by malls and shopping centers.

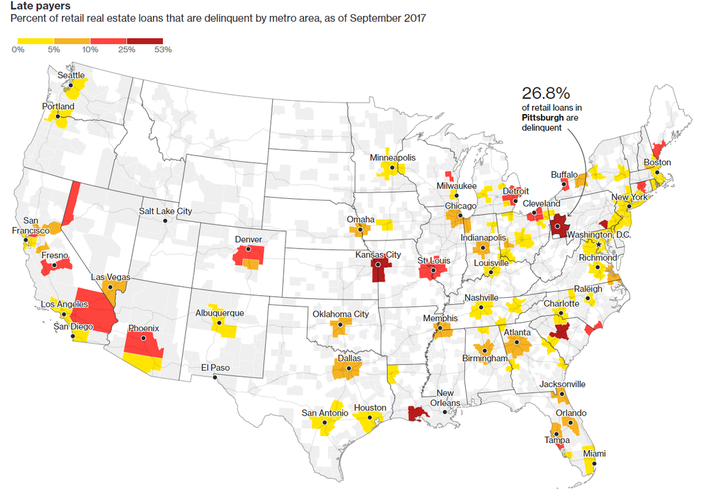

Pictured Below: Late payers as percent of retail real estate loans that are delinquent by metro area, as of September 2017

The industry’s response to that kind of doomsday description has included blaming the media for hyping the troubles of a few well-known chains as proof of a systemic meltdown. There is some truth to that. In the U.S., retailers announced more than 3,000 store openings in the first three quarters of this year.

But chains also said 6,800 would close. And this comes when there’s sky-high consumer confidence, unemployment is historically low and the U.S. economy keeps growing. Those are normally all ingredients for a retail boom, yet more chains are filing for bankruptcy and rated distressed than during the financial crisis. That’s caused an increase in the number of delinquent loan payments by malls and shopping centers.

Pictured Below: Late payers as percent of retail real estate loans that are delinquent by metro area, as of September 2017

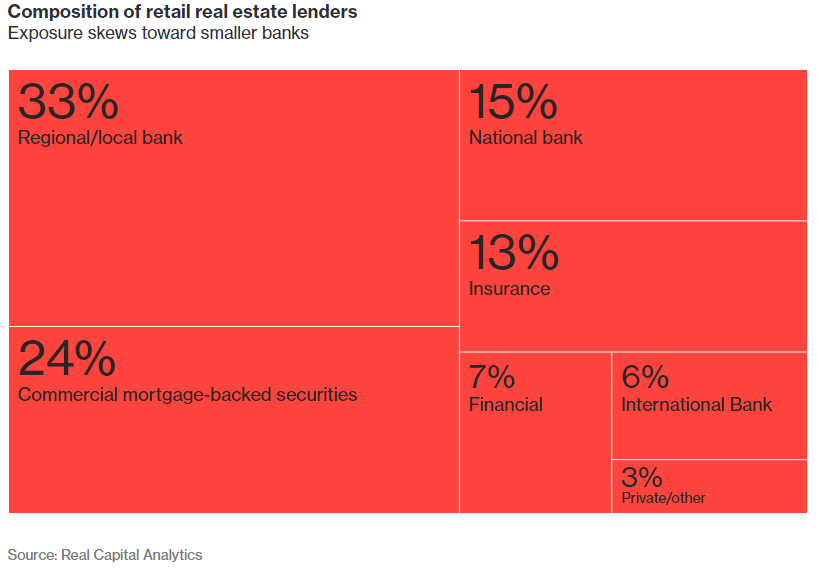

The reason isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms. There are billions in borrowings on the balance sheets of troubled retailers, and sustaining that load is only going to become harder—even for healthy chains.

The debt coming due, along with America’s over-stored suburbs and the continued gains of online shopping, has all the makings of a disaster. The spillover will likely flow far and wide across the U.S. economy. There will be displaced low-income workers, shrinking local tax bases and investor losses on stocks, bonds and real estate. If today is considered a retail apocalypse, then what’s coming next could truly be scary.

Until this year, struggling retailers have largely been able to avoid bankruptcy by refinancing to buy more time. But the market has shifted, with the negative view on retail pushing investors to reconsider lending to them.

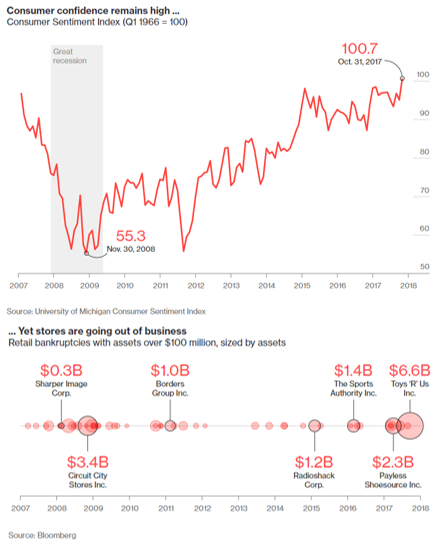

Toys “R” Us Inc. served as an early sign of what might lie ahead. It surprised investors in September by filing for bankruptcy—the third-largest retail bankruptcy in U.S. history—after struggling to refinance just $400 million of its $5 billion in debt. And its results were mostly stable, with profitability increasing amid a small drop in sales.

Pictured below: (Consumer Confidence) vs. Stores going about of Business

The debt coming due, along with America’s over-stored suburbs and the continued gains of online shopping, has all the makings of a disaster. The spillover will likely flow far and wide across the U.S. economy. There will be displaced low-income workers, shrinking local tax bases and investor losses on stocks, bonds and real estate. If today is considered a retail apocalypse, then what’s coming next could truly be scary.

Until this year, struggling retailers have largely been able to avoid bankruptcy by refinancing to buy more time. But the market has shifted, with the negative view on retail pushing investors to reconsider lending to them.

Toys “R” Us Inc. served as an early sign of what might lie ahead. It surprised investors in September by filing for bankruptcy—the third-largest retail bankruptcy in U.S. history—after struggling to refinance just $400 million of its $5 billion in debt. And its results were mostly stable, with profitability increasing amid a small drop in sales.

Pictured below: (Consumer Confidence) vs. Stores going about of Business

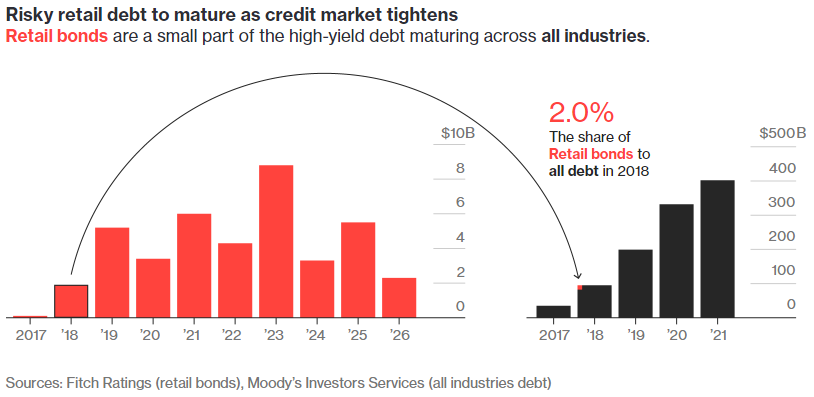

Making matters more difficult is the explosive amount of risky debt owed by retail coming due over the next five years. Several companies are like teen-jewelry chain Claire’s Stores Inc., a 2007 leveraged buyout owned by private-equity firm Apollo Global Management LLC, which has $2 billion in borrowings starting to mature in 2019 and still has 1,600 stores in North America.

Just $100 million of high-yield retail borrowings were set to mature in 2017, but that will increase to $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Fitch Ratings Inc. And from 2019 to 2025, it will balloon to an annual average of almost $5 billion. The amount of retail debt considered risky is also rising. Over the past year, high-yield bonds outstanding gained 20 percent, to $35 billion, and the industry’s leveraged loans are up 15 percent, to $152 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

Even worse, this will hit as a record $1 trillion in high-yield debt for all industries comes due over the next five years, according to Moody’s. The surge in demand for refinancing is also likely to come just as credit markets tighten and become much less accommodating to distressed borrowers.

Just $100 million of high-yield retail borrowings were set to mature in 2017, but that will increase to $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Fitch Ratings Inc. And from 2019 to 2025, it will balloon to an annual average of almost $5 billion. The amount of retail debt considered risky is also rising. Over the past year, high-yield bonds outstanding gained 20 percent, to $35 billion, and the industry’s leveraged loans are up 15 percent, to $152 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

Even worse, this will hit as a record $1 trillion in high-yield debt for all industries comes due over the next five years, according to Moody’s. The surge in demand for refinancing is also likely to come just as credit markets tighten and become much less accommodating to distressed borrowers.

Retailers have pushed off a reckoning because interest rates have been historically low from all the money the Federal Reserve has pumped into the economy since the financial crisis.

That’s made investing in riskier debt—and the higher return it brings—more attractive. But with the Fed now raising rates, that demand will soften. That may leave many chains struggling to refinance, especially with the bearishness on retail only increasing.

One testament to that negativity on retail came earlier this year, when Nordstrom Inc.’s founding family tried to take the department-store chain private. They eventually gave up because lenders were asking for 13 percent interest, about twice the typical rate for retailers.

That’s made investing in riskier debt—and the higher return it brings—more attractive. But with the Fed now raising rates, that demand will soften. That may leave many chains struggling to refinance, especially with the bearishness on retail only increasing.

One testament to that negativity on retail came earlier this year, when Nordstrom Inc.’s founding family tried to take the department-store chain private. They eventually gave up because lenders were asking for 13 percent interest, about twice the typical rate for retailers.

Store credit cards pose additional worries. Synchrony Financial, the largest private-label card issuer, has already had to increase reserves to help cover loan losses this year. And Citigroup Inc., the world’s largest card issuer, said collection rates on its retail portfolio are declining. One reason that’s been cited is that shoppers are more willing to stop paying back a card from a chain if the store they went to has closed.

The ripple effect could also be a direct hit to the industry that is the largest employer of Americans at the low end of the income scale. The most recent government statistics show that salespeople and cashiers in the industry total 8 million.

During the height of the financial crisis, store workers felt the brunt of the pain when 1.2 million jobs disappeared, or one in seven of all the positions lost from 2008 to 2009, according to the Department of Labor. Since the crisis, employment has been increasing, including in the retail industry, but that correlation ended as jobs at stores sank by 101,000 this year.

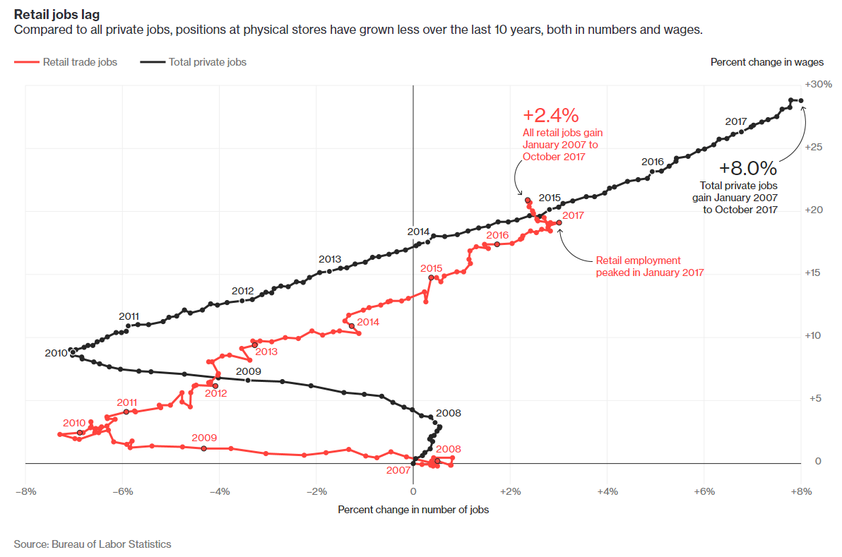

Pictured below: Retail Jobs Lag: compared to all private jobs, positions at physical stores have grown less over the last 10 years, both in numbers and wages.

The ripple effect could also be a direct hit to the industry that is the largest employer of Americans at the low end of the income scale. The most recent government statistics show that salespeople and cashiers in the industry total 8 million.

During the height of the financial crisis, store workers felt the brunt of the pain when 1.2 million jobs disappeared, or one in seven of all the positions lost from 2008 to 2009, according to the Department of Labor. Since the crisis, employment has been increasing, including in the retail industry, but that correlation ended as jobs at stores sank by 101,000 this year.

Pictured below: Retail Jobs Lag: compared to all private jobs, positions at physical stores have grown less over the last 10 years, both in numbers and wages.

The drop coincides with a rapid acceleration in store closings as bankruptcies surge and many of the nation’s largest retailers, including WalMart Stores Inc. and Target Corp., have decided that they have too much space. Even before the e-commerce boom, the U.S. was considered over-stored—the result of investors pouring money into commercial real estate decades earlier as the suburbs boomed.

All those buildings needed to be filled with stores, and that demand got the attention of venture capital. The result was the birth of the big-box era of massive stores in nearly every category—from office suppliers like Staples Inc. to pet retailers such as PetSmart Inc. and Petco Animal Supplies, Inc.

Now that boom is finally going bust. Through the third quarter of this year, 6,752 locations were scheduled to shutter in the U.S., excluding grocery stores and restaurants, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers. That's more than double the 2016 total and is close to surpassing the all-time high of 6,900 in 2008, during the depths of the financial crisis. Apparel chains have by far taken the biggest hit, with 2,500 locations closing.

Department stores were hammered, too, with Macy’s Inc., Sears Holdings Corp. and J.C. Penney Co. downsizing. In all, about 550 department stores closed, equating to 43 million square feet, or about half the total.

All those buildings needed to be filled with stores, and that demand got the attention of venture capital. The result was the birth of the big-box era of massive stores in nearly every category—from office suppliers like Staples Inc. to pet retailers such as PetSmart Inc. and Petco Animal Supplies, Inc.

Now that boom is finally going bust. Through the third quarter of this year, 6,752 locations were scheduled to shutter in the U.S., excluding grocery stores and restaurants, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers. That's more than double the 2016 total and is close to surpassing the all-time high of 6,900 in 2008, during the depths of the financial crisis. Apparel chains have by far taken the biggest hit, with 2,500 locations closing.

Department stores were hammered, too, with Macy’s Inc., Sears Holdings Corp. and J.C. Penney Co. downsizing. In all, about 550 department stores closed, equating to 43 million square feet, or about half the total.

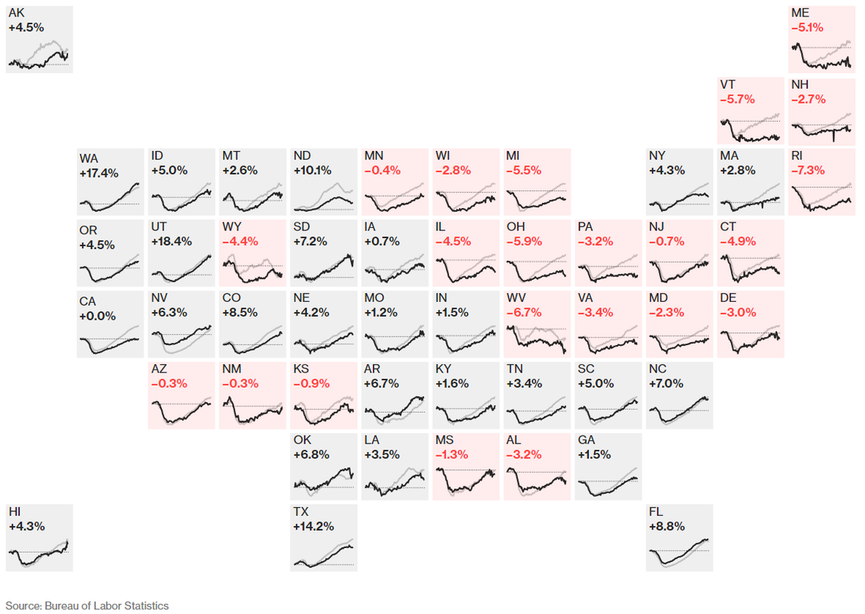

States like Ohio, West Virginia, Michigan and Illinois have been among the hardest hit, with retail employment declining over the past decade, and now those woes are likely to spread.

Many states, such as Nevada, Florida and Arkansas, have overly relied on retail for job growth, so they could feel more pain as the fallout deepens. In Washington since 2007, retail jobs have grown 3 percentage points faster than overall job growth.

New England and rust-belt states in particular have struggled, January 2007 to September 2017

Many states, such as Nevada, Florida and Arkansas, have overly relied on retail for job growth, so they could feel more pain as the fallout deepens. In Washington since 2007, retail jobs have grown 3 percentage points faster than overall job growth.

New England and rust-belt states in particular have struggled, January 2007 to September 2017

Exposure to low-end retail jobs varies by state. Alabama, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Mississippi and South Carolina have the highest concentration of cashiers, who have an average wage of $21,500 a year. And on a regional basis, Washington Parish north of New Orleans has a higher percentage than anywhere in the country, at twice the national average. Florida relies on retail salespeople more than any other state. In Sumter County, west of Orlando, retail jobs nearly doubled over the past decade.

The path to the middle class in retail is often to become a supervisor. There are 1.2 million of them, and their average annual salary is more than twice that of a cashier at $44,000. In that category, many of the same states have the most on the line, with Alabama, West Virginia, South Carolina and Montana containing the highest ratio of these workers.

One response to the loss of store-based retail jobs is to note that the industry is adding positions at distribution centers to bolster its online operations. While that is true, many displaced retail workers don’t live near a shipping facility. The hiring also skews more toward men, as they make up two-thirds of the workforce, and retail store employees are 60 percent women.

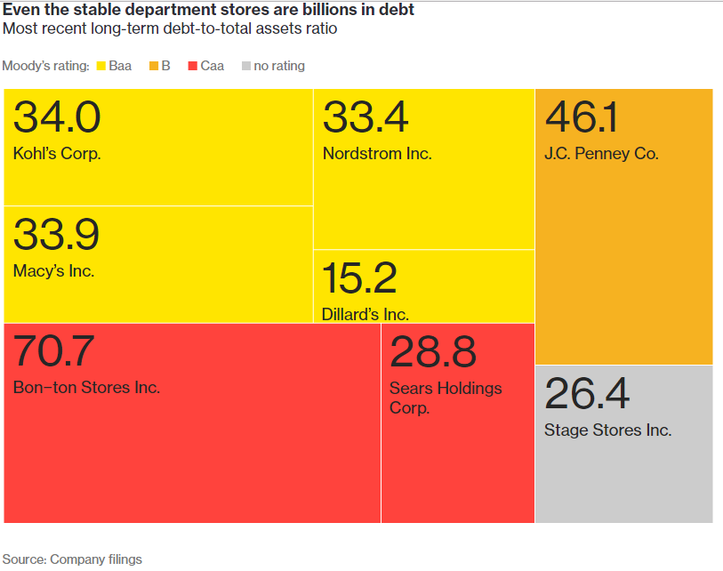

The coming wave of risky retail debt maturities doesn’t take into account that companies currently considered stable by ratings agencies also have loads of borrowings. Just among the eight publicly-traded department stores, there is about $24 billion in debt, and only two of those—Sears Holdings Corp. and Bon-Ton Stores Inc.—are rated distressed by Moody’s.

The path to the middle class in retail is often to become a supervisor. There are 1.2 million of them, and their average annual salary is more than twice that of a cashier at $44,000. In that category, many of the same states have the most on the line, with Alabama, West Virginia, South Carolina and Montana containing the highest ratio of these workers.

One response to the loss of store-based retail jobs is to note that the industry is adding positions at distribution centers to bolster its online operations. While that is true, many displaced retail workers don’t live near a shipping facility. The hiring also skews more toward men, as they make up two-thirds of the workforce, and retail store employees are 60 percent women.

The coming wave of risky retail debt maturities doesn’t take into account that companies currently considered stable by ratings agencies also have loads of borrowings. Just among the eight publicly-traded department stores, there is about $24 billion in debt, and only two of those—Sears Holdings Corp. and Bon-Ton Stores Inc.—are rated distressed by Moody’s.

“A pall has been cast on retail,” said Charlie O’Shea, a retail analyst for Moody’s. “A day of reckoning is coming.”

[End of Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

Retail Apocalypse by Wikipedia

The retail apocalypse refers to the closing of a large number of American retail stores in 2015 and expected to peak in 2018. Over 4,000 physical stores are affected as American consumers shift their purchasing habits due to various factors, including the rise of e-commerce.

Major department stores such as J.C. Penney and Macy’s have announced hundreds of store closures, and well-known apparel brands such as J. Crew and Ralph Lauren are unprofitable.

Of the 1,200 shopping malls across the US, 50% are expected to close by 2023. More than 12,000 stores are expected to close in 2018. The retail apocalypse phenomenon is related to the middle-class squeeze, in which consumers experience a decrease in income while costs increase for education, healthcare, and housing.

Bloomberg stated that the cause of the retail apocalypse “isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms.”

Forbes has said the media coverage is exaggerated, and the sector is simply evolving. The most productive retailers in the US during the retail apocalypse are the low-cost, “fast-fashion” brands (e.g. Zara and H&M) and dollar stores (e.g. Dollar General and Family Dollar).

Since at least 2010, various economic factors have resulted in the closing of a large number of American retailers, particularly in the department store industry. Sears Holdings, which had 3,555 Kmart and Sears stores in 2010, was down to 1,503 as of 2016, with more closures scheduled.

Kmart, which operated 2,171 stores at its peak in 2000, a number that has since dwindled to less than 750 with further closures planned.

The term "retail apocalypse" began gaining widespread usage in 2017 following multiple announcements from many major retailers of plans to either discontinue or greatly scale back a retail presence, including companies such as H.H. Gregg, Family Christian Stores and The Limited all going out of business entirely.

The Atlantic describes the phenomenon as "The Great Retail Apocalypse of 2017," reporting nine retail bankruptcies and several apparel companies having their stock hit new lows, including that of Lululemon, Urban Outfitters, American Eagle. Credit Suisse, a major global financial services company, predicted that 25% of U.S. malls remaining in 2017 could close by 2022.

Factors:

The main factor cited in the closing of retail stores in the retail apocalypse is the shift in consumer habits towards online commerce.

Holiday sales for e-commerce were reported as increasing by 11% for 2016 compared with 2015 by Adobe Digital Insights, with Slice Intelligence reporting an even more generous 20% increase.

Comparatively, brick-and-mortar stores saw an overall increase of only 1.6%, with physical department stores experiencing a 4.8% decline.

Another factor is an over-supply of malls, as the growth rate of malls between 1970 and 2015 was over twice the growth rate of the population. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote that investment in malls was artificially accelerated when the U.S. Congress introduced accelerated depreciation into the tax code in 1954.

Despite the construction of new malls, mall visits declined by 50% between 2010-2013 with further declines reported in each successive year.

A third major reported factor is the "restaurant renaissance," a shift in consumer spending habits for their disposable cash from material purchases such as clothing towards dining out and travel.

Another cited factor is the "death of the American middle class," resulting in large-scale closures of retailers such as Macy's and Sears, which traditionally relied on spending from this market segment.

The final factor in poor brick-and-mortar sales performance is a combination of poor retail management coupled with an overcritical eye towards quarterly dividends: a lack of accurate inventory control creates both under-performing and out-of-stock merchandise, causing a poor shopping experience for customers in order to optimize short-term balance sheets, the latter of which also influences the desire to under-staff retail stores in order to keep claimed profits high.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Retail Apocalypse:

See also:

[End of Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

Retail Apocalypse by Wikipedia

The retail apocalypse refers to the closing of a large number of American retail stores in 2015 and expected to peak in 2018. Over 4,000 physical stores are affected as American consumers shift their purchasing habits due to various factors, including the rise of e-commerce.

Major department stores such as J.C. Penney and Macy’s have announced hundreds of store closures, and well-known apparel brands such as J. Crew and Ralph Lauren are unprofitable.

Of the 1,200 shopping malls across the US, 50% are expected to close by 2023. More than 12,000 stores are expected to close in 2018. The retail apocalypse phenomenon is related to the middle-class squeeze, in which consumers experience a decrease in income while costs increase for education, healthcare, and housing.

Bloomberg stated that the cause of the retail apocalypse “isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms.”

Forbes has said the media coverage is exaggerated, and the sector is simply evolving. The most productive retailers in the US during the retail apocalypse are the low-cost, “fast-fashion” brands (e.g. Zara and H&M) and dollar stores (e.g. Dollar General and Family Dollar).

Since at least 2010, various economic factors have resulted in the closing of a large number of American retailers, particularly in the department store industry. Sears Holdings, which had 3,555 Kmart and Sears stores in 2010, was down to 1,503 as of 2016, with more closures scheduled.

Kmart, which operated 2,171 stores at its peak in 2000, a number that has since dwindled to less than 750 with further closures planned.

The term "retail apocalypse" began gaining widespread usage in 2017 following multiple announcements from many major retailers of plans to either discontinue or greatly scale back a retail presence, including companies such as H.H. Gregg, Family Christian Stores and The Limited all going out of business entirely.

The Atlantic describes the phenomenon as "The Great Retail Apocalypse of 2017," reporting nine retail bankruptcies and several apparel companies having their stock hit new lows, including that of Lululemon, Urban Outfitters, American Eagle. Credit Suisse, a major global financial services company, predicted that 25% of U.S. malls remaining in 2017 could close by 2022.

Factors:

The main factor cited in the closing of retail stores in the retail apocalypse is the shift in consumer habits towards online commerce.

Holiday sales for e-commerce were reported as increasing by 11% for 2016 compared with 2015 by Adobe Digital Insights, with Slice Intelligence reporting an even more generous 20% increase.

Comparatively, brick-and-mortar stores saw an overall increase of only 1.6%, with physical department stores experiencing a 4.8% decline.

Another factor is an over-supply of malls, as the growth rate of malls between 1970 and 2015 was over twice the growth rate of the population. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote that investment in malls was artificially accelerated when the U.S. Congress introduced accelerated depreciation into the tax code in 1954.

Despite the construction of new malls, mall visits declined by 50% between 2010-2013 with further declines reported in each successive year.

A third major reported factor is the "restaurant renaissance," a shift in consumer spending habits for their disposable cash from material purchases such as clothing towards dining out and travel.

Another cited factor is the "death of the American middle class," resulting in large-scale closures of retailers such as Macy's and Sears, which traditionally relied on spending from this market segment.

The final factor in poor brick-and-mortar sales performance is a combination of poor retail management coupled with an overcritical eye towards quarterly dividends: a lack of accurate inventory control creates both under-performing and out-of-stock merchandise, causing a poor shopping experience for customers in order to optimize short-term balance sheets, the latter of which also influences the desire to under-staff retail stores in order to keep claimed profits high.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Retail Apocalypse:

- Affected retailers, beginning with:

See also:

- Dead mall

- Amazon.com

- Experience economy

- Generation Z

- Economic history of the United States

- Brian Sozzi, Coach CEO Perfectly Explains What Must Be Done to Survive Retail Apocalypse thestreet.com September 8, 2017

- The Death Knell for the Bricks-and-Mortar Store? Not Yet MATTHEW SCHNEIER, New York Times, November 13, 2017

- What It's Like to Work in the Last Big Store in a Dying Mall Washington Post/Newser, Kate Seamons, January 2, 2018

Consumer Protection Laws in the United States including Anti-trust Laws and the Federal Trade Commission as well as the Breakup of the AT&T Bell companies in 1982

YouTube Video: What is the U.S. Federal Trade Commission Act?

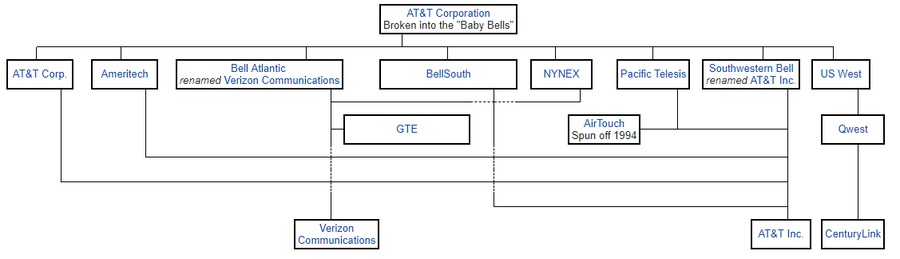

Pictured below: Graphic of the forced breakup of AT&T in 1982, into"Baby Bells"

In regulatory jurisdictions that provide for it (comprising most or all developed countries with free market economies), consumer protection is a group of laws and organizations designed to ensure the rights of consumers as well as fair trade, competition and accurate information in the marketplace.

The laws are designed to prevent the businesses that engage in fraud or specified unfair practices from gaining an advantage over competitors. They may also provide additional protection for those most vulnerable in society.

Consumer protection laws are a form of government regulation that aim to protect the rights of consumers. For example, a government may require businesses to disclose detailed information about products—particularly in areas where safety or public health is an issue, such as food.

Consumer protection is linked to the idea of consumer rights and to the formation of consumer organizations, which help consumers make better choices in the marketplace and get help with consumer complaints. Other organizations that promote consumer protection include government organizations and self-regulating business organizations such as consumer protection agencies and organizations, ombudsmen, the Federal Trade Commission in America and Better Business Bureaus in America and Canada, etc.

A consumer is defined as someone who acquires goods or services for direct use or ownership rather than for resale or use in production and manufacturing.

Consumer interests can also be protected by promoting competition in the markets which directly and indirectly serve consumers, consistent with economic efficiency, but this topic is treated in competition law. Consumer protection can also be asserted via non-government organizations and individuals as consumer activism.

Consumer Protection in the United States:

In the United States a variety of laws at both the federal and state levels regulate consumer affairs. Among them are the following Federal agencies:

Federal consumer protection laws are mainly enforced by the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Food and Drug Administration, and the U.S. Department of Justice.

At the state level, many states have adopted the Uniform Deceptive Trade Practices Act including, but not limited to, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, and Nebraska. The deceptive trade practices prohibited by the Uniform Act can be roughly subdivided into conduct involving either a) unfair or fraudulent business practice and b) untrue or misleading advertising.

The Uniform Act contains a private remedy with attorneys fees for prevailing parties where the losing party "willfully engaged in the trade practice knowing it to be deceptive". Uniform Act §3(b).

Missouri has a similar statute called the Merchandising Practices Act. This statute allows local prosecutors or the Attorney General to press charges against people who knowingly use deceptive business practices in a consumer transaction and authorizes consumers to hire a private attorney to bring an action seeking their actual damages, punitive damages, and attorney's fees.

Also, the majority of states have a Department of Consumer Affairs devoted to regulating certain industries and protecting consumers who use goods and services from those industries.

For example, in California, the California Department of Consumer Affairs regulates about 2.3 million professionals in over 230 different professions, through its forty regulatory entities. In addition, California encourages its consumers to act as private attorneys general through the liberal provisions of its Consumers Legal Remedies Act.

California has the strongest consumer protection laws of any US state, partly because of rigorous advocacy and lobbying by groups such as Utility Consumers' Action Network, Consumer Federation of California, and Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. For example, California provides for "cooling off" periods giving consumers the right to cancel contracts within a certain time period for several specified types of transactions, such as home secured transactions, and warranty and repair services contracts.

Other states have been the leaders in specific aspects of consumer protection. For example, Florida, Delaware, and Minnesota have legislated requirements that contracts be written at reasonable readability levels as a large proportion of contracts cannot be understood by most consumers who sign them.

Consumer Protection Laws in the United States:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Consumer Protection:

United States antitrust law:

United States antitrust law is a collection of federal and state government laws that regulates the conduct and organization of business corporations, generally to promote fair competition for the benefit of consumers. (The concept is called competition law in other English-speaking countries.)

The main statutes are the Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914 and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. These Acts, first, restrict the formation of cartels and prohibit other collusive practices regarded as being in restraint of trade.

Second, they restrict the mergers and acquisitions of organizations that could substantially lessen competition. Third, they prohibit the creation of a monopoly and the abuse of monopoly power.

The Federal Trade Commission, the U.S. Department of Justice, state governments and private parties who are sufficiently affected may all bring actions in the courts to enforce the antitrust laws. The scope of antitrust laws, and the degree to which they should interfere in an enterprise's freedom to conduct business, or to protect smaller businesses, communities and consumers, are strongly debated.

One view, mostly closely associated with the "Chicago School of economics" suggests that antitrust laws should focus solely on the benefits to consumers and overall efficiency, while a broad range of legal and economic theory sees the role of antitrust laws as also controlling economic power in the public interest.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about United States Antitrust Laws:

United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC):

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government, established in 1914 by the Federal Trade Commission Act. Its principal mission is the promotion of consumer protection and the elimination and prevention of anti-competitive business practices, such as coercive monopoly.

The Federal Trade Commission Act was one of President Woodrow Wilson's major acts against trusts. Trusts and trust-busting were significant political concerns during the Progressive Era.

Since its inception, the FTC has enforced the provisions of the Clayton Act, a key antitrust statute, as well as the provisions of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 41 et seq.

Over time, the FTC has been delegated with the enforcement of additional business regulation statutes and has promulgated a number of regulations (codified in Title 16 of the Code of Federal Regulations).

For more about the Federal Trade Commission, click here.

___________________________________________________________________________

Breakup of the Bell System.

The breakup of the Bell System was mandated on January 8, 1982, by an agreed consent decree providing that AT&T Corporation would, as had been initially proposed by AT&T, relinquish control of the Bell Operating Companies that had provided local telephone service in the United States and Canada up until that point.

This effectively took the monopoly that was the Bell System and split it into entirely separate companies that would continue to provide telephone service. AT&T would continue to be a provider of long distance service, while the now-independent Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs) would provide local service, and would no longer be directly supplied with equipment from AT&T subsidiary Western Electric.

This divestiture was initiated by the filing in 1974 by the United States Department of Justice of an antitrust lawsuit against AT&T. AT&T was, at the time, the sole provider of telephone service throughout most of the United States.

Furthermore, most telephonic equipment in the United States was produced by its subsidiary, Western Electric. This vertical integration led AT&T to have almost total control over communication technology in the country, which led to the antitrust case, United States v. AT&T. The plaintiff in the court complaint asked the court to order AT&T to divest ownership of Western Electric.

Feeling that it was about to lose the suit, AT&T proposed an alternative — the breakup of the biggest corporation in American history. It proposed that it retain control of Western Electric, Yellow Pages, the Bell trademark, Bell Labs, and AT&T Long Distance.

It also proposed that it be freed from a 1956 antitrust consent decree, then administered by Judge Vincent Pasquale Biunno in the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, that barred it from participating in the general sale of computers

In return, it proposed to give up ownership of the local operating companies. This last concession, it argued, would achieve the Government's goal of creating competition in supplying telephone equipment and supplies to the operative companies.

The settlement was finalized on January 8, 1982, with some changes ordered by the decree court: the regional holding companies got the Bell trademark, Yellow Pages, and about half of Bell Labs.

Effective January 1, 1984, the Bell System’s many member companies were variously merged into seven independent "Regional Holding Companies", also known as Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs), or "Baby Bells". This divestiture reduced the book value of AT&T by approximately 70%

Click here for more about the Breakup of the Bell System.

The laws are designed to prevent the businesses that engage in fraud or specified unfair practices from gaining an advantage over competitors. They may also provide additional protection for those most vulnerable in society.