Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

This Page primarily covers the Economy of the United States, including how the United States impacts, and is impacted by, the Global Economy

The Economy of the United States and The World

YouTube Video: An Overview of Macroeconomics by University of California, Berkely, CA

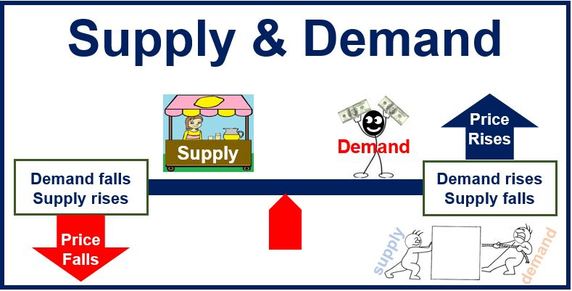

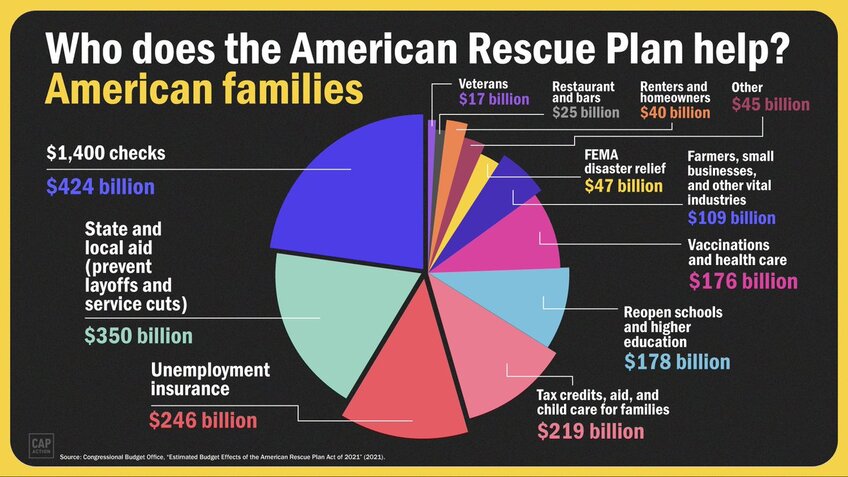

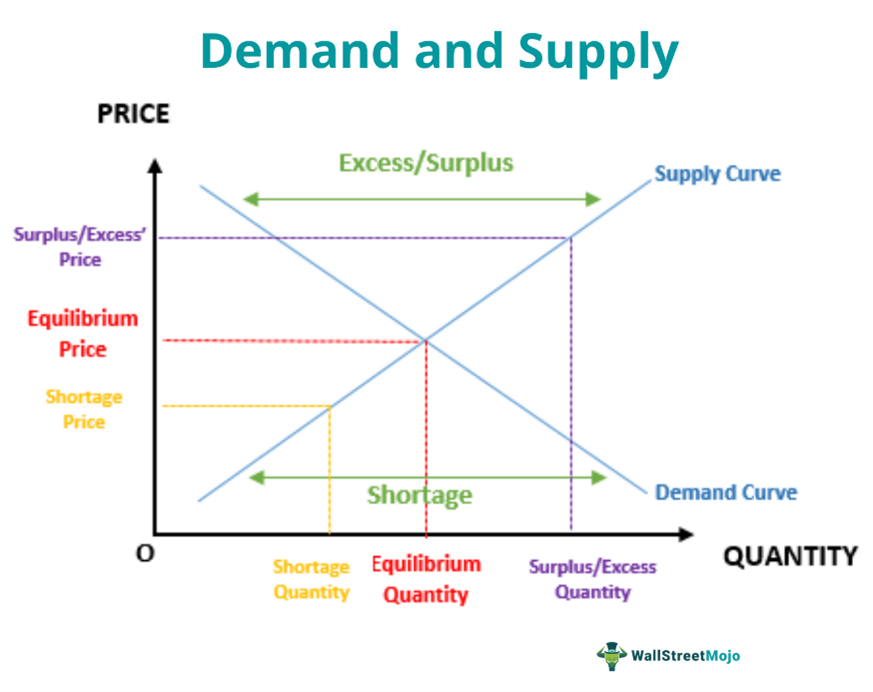

Pictured: The Role of Supply and Demand

An economy is the production, distribution, or trade, and economic consumption of goods and services by a country. Understood in its broadest sense, 'The economic is defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the production, use and management of resources'.

Economic agents can be individuals, businesses, organizations, or governments. Economic transactions occur when two parties agree to the value or price of the transacted good or service, commonly expressed in a certain currency, but monetary transactions are only a small part of the economic domain.

Economic activity is spurred by production which uses natural resources, labor, and capital. It has changed over time due to

A given economy is the result of a set of processes that involves its culture, values, education, technological evolution, history, social organization, political structure and legal systems, as well as its geography, natural resource endowment, and ecology, as main factors.

These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions. In other words, the economic domain is a social domain of human practices and transactions. It does not stand alone.

A market-based economy is where goods and services are produced and exchanged according to demand and supply between participants (economic agents) by barter or a medium of exchange with a credit or debit value accepted within the network, such as a unit of currency.

A command-based economy is where political agents directly control what is produced and how it is sold and distributed.

A green economy is low-carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive. In a green economy, growth in income and employment are driven by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency, and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

The Economy of the United States:

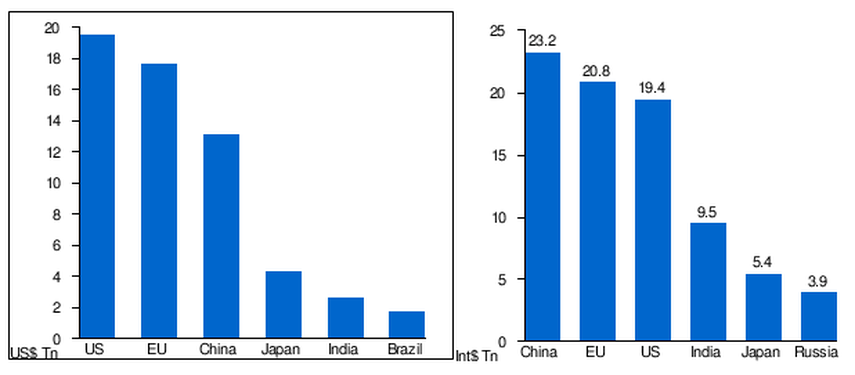

The United States is the world's largest national economy in nominal terms and second largest according to purchasing power parity (PPP), representing 22% of nominal global GDP and 17% of gross world product (GWP).

The United States' GDP was estimated to be $17.914 trillion as of Q2 2015. The U.S. dollar is the currency most used in international transactions and is the world's foremost reserve currency. Several countries use it as their official currency, and in many others it is the de facto currency.

The United States has a mixed economy and has maintained a stable overall GDP growth rate, a moderate unemployment rate, and high levels of research and capital investment.

Its seven largest trading partners are Canada, China, Mexico, Japan, Germany, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

The US has abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, and high productivity. It has the world's ninth-highest per capita GDP (nominal) and tenth-highest per capita GDP (PPP) as of 2013.

Americans have the highest average household and employee income among OECD nations, and in 2010 had the fourth highest median household income, down from second highest in 2007. It has been the world's largest national economy (not including colonial empires) since at least the 1890s.

The U.S. is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas.

It is one of the largest trading nations in the world as well as the world's second largest manufacturer, representing a fifth of the global manufacturing output. The US not only has the largest internal market for goods, but also dominates the trade in services. US total trade amounted to $4.93T in 2012. Of the world's 500 largest companies, 128 are headquartered in the US.

The United States has one of the world's largest and most influential financial markets. The New York Stock Exchange is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization. Foreign investments made in the US total almost $2.4 trillion, while American investments in foreign countries total over $3.3 trillion.

The economy of the U.S. leads in international ranking on venture capital and Global Research and Development funding. Consumer spending comprises 71% of the US economy in 2013.

The United States has the largest consumer market in the world, with a household final consumption expenditure five times larger than Japan's. The labor market has attracted immigrants from all over the world and its net migration rate is among the highest in the world. The U.S. is one of the top-performing economies in studies such as the Ease of Doing Business Index, the Global Competitiveness Report, and others.

The US economy went through an economic downturn following the financial crisis of 2007–08, with output as late as 2013 still below potential according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The economy, however, began to recover in the second half of 2009, and as of November 2015, unemployment had declined from a high of 10% to 5%. In December 2014, public debt was slightly more than 100% of GDP. Domestic financial assets totaled $131 trillion and domestic financial liabilities totaled $106 trillion.

The World Economy:

The world economy or global economy is the economy of the world, considered as the international exchange of goods and services that is expressed in monetary units of account (money).

In some contexts, the two terms are distinguished: the "international" or "global economy" being measured separately and distinguished from national economies while the "world economy" is simply an aggregate of the separate countries' measurements. Beyond the minimum standard concerning value in production, use, and exchange the definitions, representations, models, and valuations of the world economy vary widely. It is inseparable from the geography and ecology of Earth.

It is common to limit questions of the world economy exclusively to human economic activity, and the world economy is typically judged in monetary terms, even in cases in which there is no efficient market to help valuate certain goods or services, or in cases in which a lack of independent research or government cooperation makes establishing figures difficult. Typical examples are illegal drugs and other black market goods, which by any standard are a part of the world economy, but for which there is by definition no legal market of any kind.

However, even in cases in which there is a clear and efficient market to establish a monetary value, economists do not typically use the current or official exchange rate to translate the monetary units of this market into a single unit for the world economy, since exchange rates typically do not closely reflect worldwide value, for example in cases where the volume or price of transactions is closely regulated by the government.

World share of GDP (PPP) (World Bank, 2011).

Rather, market valuations in a local currency are typically translated to a single monetary unit using the idea of purchasing power. This is the method used below, which is used for estimating worldwide economic activity in terms of real US dollars or euros. However, the world economy can be evaluated and expressed in many more ways. It is unclear, for example, how many of the world's 7.13 billion people have most of their economic activity reflected in these valuations.

As of 2015, the following 13 countries or regions have reached an economy of at least US$2 trillion by GDP in nominal or PPP terms:

Economic agents can be individuals, businesses, organizations, or governments. Economic transactions occur when two parties agree to the value or price of the transacted good or service, commonly expressed in a certain currency, but monetary transactions are only a small part of the economic domain.

Economic activity is spurred by production which uses natural resources, labor, and capital. It has changed over time due to

- technology (automation, accelerator of process, reduction of cost functions),

- innovation (new products, services, processes, new markets, expands markets, diversification of markets, niche markets, increases revenue functions) such as that which produces intellectual property,

- and changes in industrial relations (for example, child labor being replaced in some parts of the world with universal access to education).

A given economy is the result of a set of processes that involves its culture, values, education, technological evolution, history, social organization, political structure and legal systems, as well as its geography, natural resource endowment, and ecology, as main factors.

These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions. In other words, the economic domain is a social domain of human practices and transactions. It does not stand alone.

A market-based economy is where goods and services are produced and exchanged according to demand and supply between participants (economic agents) by barter or a medium of exchange with a credit or debit value accepted within the network, such as a unit of currency.

A command-based economy is where political agents directly control what is produced and how it is sold and distributed.

A green economy is low-carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive. In a green economy, growth in income and employment are driven by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency, and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

The Economy of the United States:

The United States is the world's largest national economy in nominal terms and second largest according to purchasing power parity (PPP), representing 22% of nominal global GDP and 17% of gross world product (GWP).

The United States' GDP was estimated to be $17.914 trillion as of Q2 2015. The U.S. dollar is the currency most used in international transactions and is the world's foremost reserve currency. Several countries use it as their official currency, and in many others it is the de facto currency.

The United States has a mixed economy and has maintained a stable overall GDP growth rate, a moderate unemployment rate, and high levels of research and capital investment.

Its seven largest trading partners are Canada, China, Mexico, Japan, Germany, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

The US has abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, and high productivity. It has the world's ninth-highest per capita GDP (nominal) and tenth-highest per capita GDP (PPP) as of 2013.

Americans have the highest average household and employee income among OECD nations, and in 2010 had the fourth highest median household income, down from second highest in 2007. It has been the world's largest national economy (not including colonial empires) since at least the 1890s.

The U.S. is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas.

It is one of the largest trading nations in the world as well as the world's second largest manufacturer, representing a fifth of the global manufacturing output. The US not only has the largest internal market for goods, but also dominates the trade in services. US total trade amounted to $4.93T in 2012. Of the world's 500 largest companies, 128 are headquartered in the US.

The United States has one of the world's largest and most influential financial markets. The New York Stock Exchange is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization. Foreign investments made in the US total almost $2.4 trillion, while American investments in foreign countries total over $3.3 trillion.

The economy of the U.S. leads in international ranking on venture capital and Global Research and Development funding. Consumer spending comprises 71% of the US economy in 2013.

The United States has the largest consumer market in the world, with a household final consumption expenditure five times larger than Japan's. The labor market has attracted immigrants from all over the world and its net migration rate is among the highest in the world. The U.S. is one of the top-performing economies in studies such as the Ease of Doing Business Index, the Global Competitiveness Report, and others.

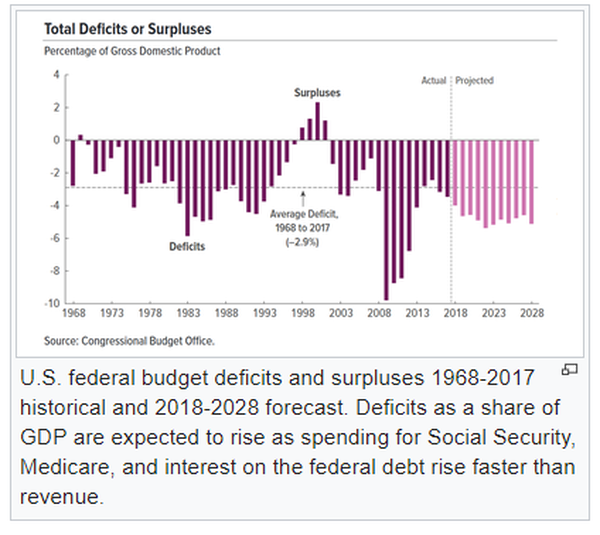

The US economy went through an economic downturn following the financial crisis of 2007–08, with output as late as 2013 still below potential according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The economy, however, began to recover in the second half of 2009, and as of November 2015, unemployment had declined from a high of 10% to 5%. In December 2014, public debt was slightly more than 100% of GDP. Domestic financial assets totaled $131 trillion and domestic financial liabilities totaled $106 trillion.

The World Economy:

The world economy or global economy is the economy of the world, considered as the international exchange of goods and services that is expressed in monetary units of account (money).

In some contexts, the two terms are distinguished: the "international" or "global economy" being measured separately and distinguished from national economies while the "world economy" is simply an aggregate of the separate countries' measurements. Beyond the minimum standard concerning value in production, use, and exchange the definitions, representations, models, and valuations of the world economy vary widely. It is inseparable from the geography and ecology of Earth.

It is common to limit questions of the world economy exclusively to human economic activity, and the world economy is typically judged in monetary terms, even in cases in which there is no efficient market to help valuate certain goods or services, or in cases in which a lack of independent research or government cooperation makes establishing figures difficult. Typical examples are illegal drugs and other black market goods, which by any standard are a part of the world economy, but for which there is by definition no legal market of any kind.

However, even in cases in which there is a clear and efficient market to establish a monetary value, economists do not typically use the current or official exchange rate to translate the monetary units of this market into a single unit for the world economy, since exchange rates typically do not closely reflect worldwide value, for example in cases where the volume or price of transactions is closely regulated by the government.

World share of GDP (PPP) (World Bank, 2011).

Rather, market valuations in a local currency are typically translated to a single monetary unit using the idea of purchasing power. This is the method used below, which is used for estimating worldwide economic activity in terms of real US dollars or euros. However, the world economy can be evaluated and expressed in many more ways. It is unclear, for example, how many of the world's 7.13 billion people have most of their economic activity reflected in these valuations.

As of 2015, the following 13 countries or regions have reached an economy of at least US$2 trillion by GDP in nominal or PPP terms:

- Brazil,

- China,

- France,

- Germany,

- India,

- Indonesia,

- Italy,

- Japan,

- Mexico,

- Russia,

- the United Kingdom,

- the United States,

- and the European Union.

Economics and Monetary Policy of the United States, including the President's Council of Economic Advisors

YouTube Video: Alan Greenspan on Brexit, U.S. Economy, and Inflation (Full Interview)

Pictured: LEFT: Study of Economics, CENTER: Monetary Policy of the United States, RIGHT: Seal of President's Council of Economic Advisors

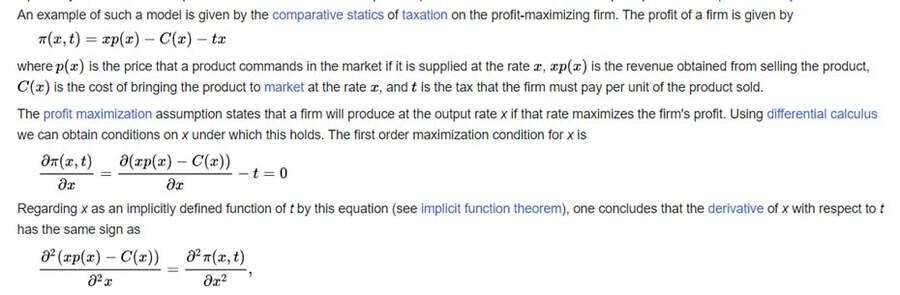

Economics is a social science concerned with the factors that determine the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

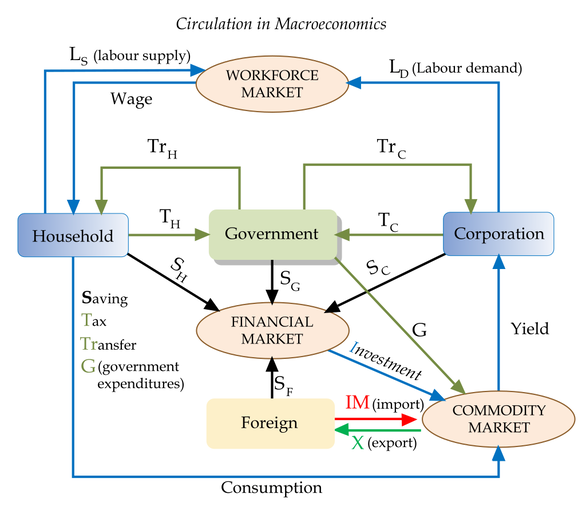

Economics focuses on the behavior and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Consistent with this focus, primary textbooks often distinguish between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Microeconomics examines the behavior of basic elements in the economy, including individual agents and markets, their interactions, and the outcomes of interactions. Individual agents may include, for example, households, firms, buyers, and sellers.

Macroeconomics analyses the entire economy (meaning aggregated production, consumption, savings, and investment) and issues affecting it, including unemployment of resources (labor, capital, and land), inflation, economic growth, and the public policies that address these issues (monetary, fiscal, and other policies).

Other broad distinctions within economics include those between positive economics, describing "what is", and normative economics, advocating "what ought to be"; between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioral economics; and between mainstream economics and heterodox economics.

Besides the traditional concern in production, distribution, and consumption in an economy, economic analysis may be applied throughout society, as in business, finance, health care, and government.

Economic analyses may also be applied to such diverse subjects as:

Education, for example, requires time, effort, and expenses, plus the foregone income and experience, yet these losses can be weighted against future benefits education may bring to the agent or the economy.

At the turn of the 21st century, the expanding domain of economics in the social sciences has been described as economic imperialism. The ultimate goal of economics is to improve the living conditions of people in their everyday life.

For more about Economics, click here.

___________________________________________________________________________

Monetary policy of the United States:

Monetary policy concerns the actions of a central bank or other regulatory authorities that determine the size and rate of growth of the money supply.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve is in charge of monetary policy, and implements it primarily by performing operations that influence short-term interest rates.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification about Monetary policy of the United States:

President's Council of Economic Advisers

The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) is an agency within the Executive Office of the President that advises the President of the United States on economic policy. The CEA provides much of the objective empirical research for the White House and prepares the annual Economic Report of the President.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

Economics focuses on the behavior and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Consistent with this focus, primary textbooks often distinguish between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Microeconomics examines the behavior of basic elements in the economy, including individual agents and markets, their interactions, and the outcomes of interactions. Individual agents may include, for example, households, firms, buyers, and sellers.

Macroeconomics analyses the entire economy (meaning aggregated production, consumption, savings, and investment) and issues affecting it, including unemployment of resources (labor, capital, and land), inflation, economic growth, and the public policies that address these issues (monetary, fiscal, and other policies).

Other broad distinctions within economics include those between positive economics, describing "what is", and normative economics, advocating "what ought to be"; between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioral economics; and between mainstream economics and heterodox economics.

Besides the traditional concern in production, distribution, and consumption in an economy, economic analysis may be applied throughout society, as in business, finance, health care, and government.

Economic analyses may also be applied to such diverse subjects as:

- crime,

- education,

- family,

- law,

- politics,

- religion,

- social institutions,

- war,

- science,

- and the environment.

Education, for example, requires time, effort, and expenses, plus the foregone income and experience, yet these losses can be weighted against future benefits education may bring to the agent or the economy.

At the turn of the 21st century, the expanding domain of economics in the social sciences has been described as economic imperialism. The ultimate goal of economics is to improve the living conditions of people in their everyday life.

For more about Economics, click here.

___________________________________________________________________________

Monetary policy of the United States:

Monetary policy concerns the actions of a central bank or other regulatory authorities that determine the size and rate of growth of the money supply.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve is in charge of monetary policy, and implements it primarily by performing operations that influence short-term interest rates.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification about Monetary policy of the United States:

- Money supply

- Structure of modern US institutions

- Federal Reserve

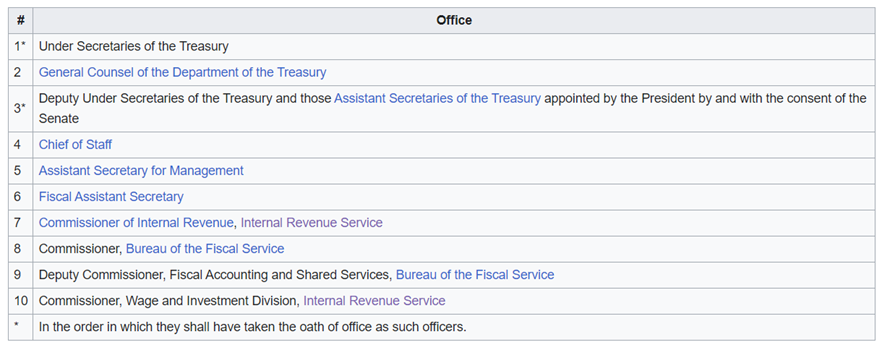

U.S. Treasury

Private commercial banks

- Federal Reserve

- Money creation

- Significant effects

- Uncertainties

- Opinions of the Federal Reserve

- See also:

President's Council of Economic Advisers

The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) is an agency within the Executive Office of the President that advises the President of the United States on economic policy. The CEA provides much of the objective empirical research for the White House and prepares the annual Economic Report of the President.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

Economic History of the United States (Since 1950)

YouTube Video: The United States in 1950 (A Simpler Time?)

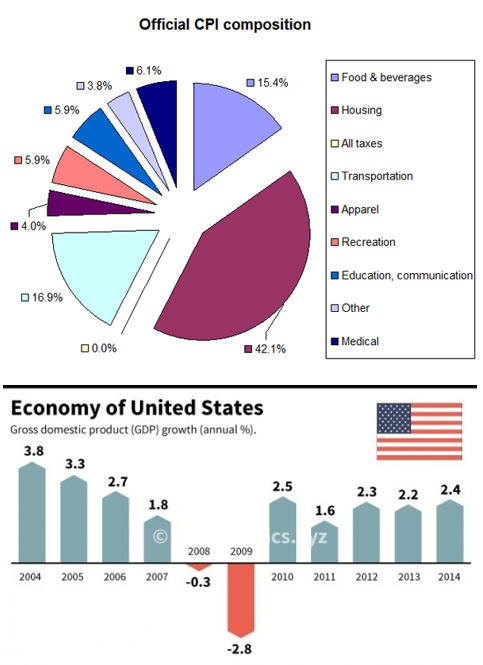

Pictured: TOP: Chart of Consumer Price Index (CPI) Composition.

BOTTOM: The economy of the United States as a measure of growth based on the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The Economic History of the United States is about characteristics of and important developments in the U.S. economy. The emphasis is on economic performance and how it was affected by new technologies, the change of size in economic sectors and the effects of legislation and government policy. Specialized teams and business history are covered in American business history.

The period from the end of World War II to the early 1970s was a golden era of economic growth. $200 billion in war bonds matured, and the G.I. Bill financed a well-educated work force.

The middle class swelled, as did GDP and productivity. This growth was distributed fairly evenly across the economic classes, which some attribute to the strength of labor unions in this period—labor union membership peaked historically in the U.S. during the 1950s, in the midst of this massive economic growth.

Much of the growth came from the movement of low income farm workers into better paying jobs in the towns and cities—a process largely completed by 1960. Congress created the Council of Economic Advisors, to promote high employment, high profits and low inflation.

The Eisenhower administration (1953–1961) supported an activist contracyclical approach that helped to establish Keynesianism as a bipartisan economic policy for the nation.

Especially important in formulating the CEA response to the recession—accelerating public works programs, easing credit, and reducing taxes—were Arthur F. Burns and Neil H. Jacoby. "I am now a Keynesian in economics", proclaimed Republican President Richard Nixon in 1969.

Although this period brought economic expansion to the country as a whole, it was not recession proof. The recessions of 1953, 1958, and 1960 saw a drastic decline in GDP.

The "Baby Boom" saw a dramatic increase in fertility in the period 1942–1957; it was caused by delayed marriages and childbearing during depression years, a surge in prosperity, a demand for suburban single-family homes (as opposed to inner city apartments) and new optimism about the future. The boom crested about 1957, then slowly declined

Click on any of the following for major developments impacting the United States since 1950:

The period from the end of World War II to the early 1970s was a golden era of economic growth. $200 billion in war bonds matured, and the G.I. Bill financed a well-educated work force.

The middle class swelled, as did GDP and productivity. This growth was distributed fairly evenly across the economic classes, which some attribute to the strength of labor unions in this period—labor union membership peaked historically in the U.S. during the 1950s, in the midst of this massive economic growth.

Much of the growth came from the movement of low income farm workers into better paying jobs in the towns and cities—a process largely completed by 1960. Congress created the Council of Economic Advisors, to promote high employment, high profits and low inflation.

The Eisenhower administration (1953–1961) supported an activist contracyclical approach that helped to establish Keynesianism as a bipartisan economic policy for the nation.

Especially important in formulating the CEA response to the recession—accelerating public works programs, easing credit, and reducing taxes—were Arthur F. Burns and Neil H. Jacoby. "I am now a Keynesian in economics", proclaimed Republican President Richard Nixon in 1969.

Although this period brought economic expansion to the country as a whole, it was not recession proof. The recessions of 1953, 1958, and 1960 saw a drastic decline in GDP.

The "Baby Boom" saw a dramatic increase in fertility in the period 1942–1957; it was caused by delayed marriages and childbearing during depression years, a surge in prosperity, a demand for suburban single-family homes (as opposed to inner city apartments) and new optimism about the future. The boom crested about 1957, then slowly declined

Click on any of the following for major developments impacting the United States since 1950:

- Agriculture

- Aircraft and air transportation industries

- Interstate highway system

- Mainframe computers

- Liberal programs

- Military and space spending

Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

YouTube Video: Introduction to the Congressional Budget Office

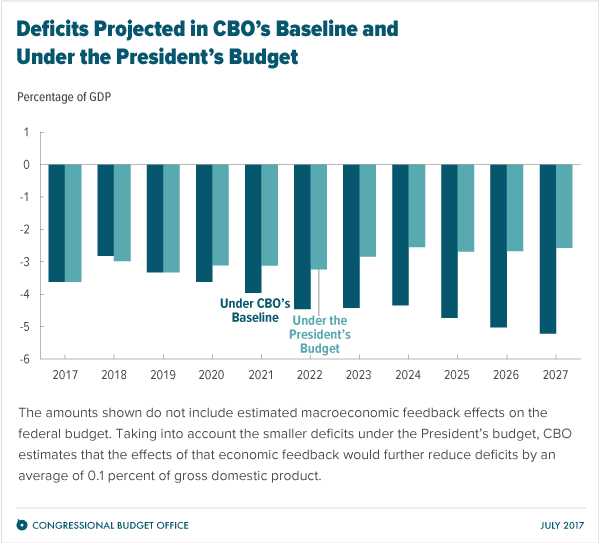

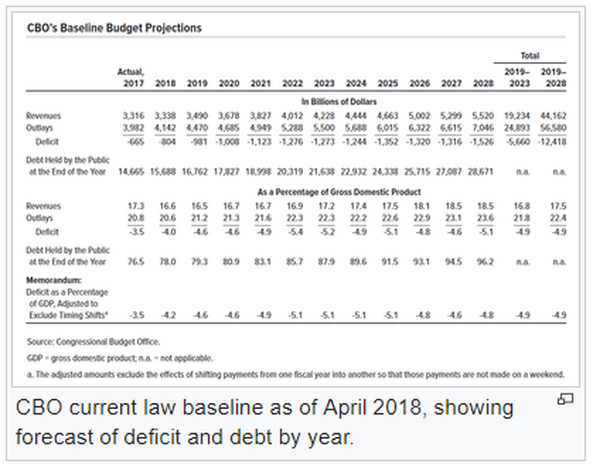

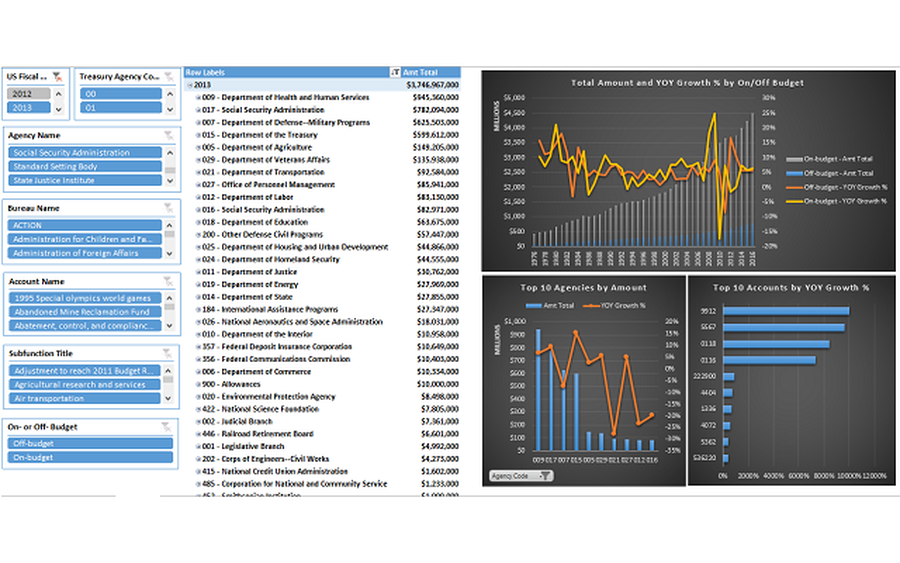

Pictured below: An Analysis of the President’s 2018 Budget

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is a federal agency within the legislative branch of the United States government that provides budget and economic information to Congress.

Inspired by California's Legislative Analyst's Office that manages the state budget in a strictly nonpartisan fashion, the CBO was created as a nonpartisan agency by the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

There is a consensus among economists that "the CBO has historically issued credible forecasts of the effects of both Democratic and Republican legislative proposals."

Mission:

The Congressional Budget Office is nonpartisan, and produces "independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process." Each year, the agency releases reports and cost estimates for proposed legislation, without issuing any policy recommendations.

With respect to estimating spending for Congress, the Congressional Budget Office serves a purpose parallel to that of the Joint Committee on Taxation for estimating revenue for Congress, the Department of the Treasury for estimating revenues for the Executive branch. This includes projections on the effect on national debt and cost estimates for legislation.

Operations:

Section 202(e) of the Budget Act requires the CBO to submit periodic reports about fiscal policy to the House and Senate budget committees to provide baseline projections of the federal budget. This is currently done by preparation of an annual Economic and Budget Outlook plus a mid-year update.

The agency also each year issues An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for the upcoming fiscal year per a standing request of the Senate Committee on Appropriations.

These three series are designated essential titles distributed to Federal Depository Libraries and are available for purchase from the Government Publishing Office. The CBO often provides testimony in response to requests from various Congressional committees and issues letters responding to queries made by members of Congress.

Departmental Divisions:

The Congressional Budget Office is divided into eight divisions:

Click on the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Congressional Budget Office (CBO):

Inspired by California's Legislative Analyst's Office that manages the state budget in a strictly nonpartisan fashion, the CBO was created as a nonpartisan agency by the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

There is a consensus among economists that "the CBO has historically issued credible forecasts of the effects of both Democratic and Republican legislative proposals."

Mission:

The Congressional Budget Office is nonpartisan, and produces "independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process." Each year, the agency releases reports and cost estimates for proposed legislation, without issuing any policy recommendations.

With respect to estimating spending for Congress, the Congressional Budget Office serves a purpose parallel to that of the Joint Committee on Taxation for estimating revenue for Congress, the Department of the Treasury for estimating revenues for the Executive branch. This includes projections on the effect on national debt and cost estimates for legislation.

Operations:

Section 202(e) of the Budget Act requires the CBO to submit periodic reports about fiscal policy to the House and Senate budget committees to provide baseline projections of the federal budget. This is currently done by preparation of an annual Economic and Budget Outlook plus a mid-year update.

The agency also each year issues An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for the upcoming fiscal year per a standing request of the Senate Committee on Appropriations.

These three series are designated essential titles distributed to Federal Depository Libraries and are available for purchase from the Government Publishing Office. The CBO often provides testimony in response to requests from various Congressional committees and issues letters responding to queries made by members of Congress.

Departmental Divisions:

The Congressional Budget Office is divided into eight divisions:

- Budget Analysis

- Financial Analysis

- Health, Retirement, and Long-Term Analysis

- Macroeconomic Analysis

- Management, Business, and Information Services

- Microeconomic Studies

- National Security

- Tax Analysis

Click on the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Congressional Budget Office (CBO):

Causes of Income Inequality in the United States and their impact on America's Shrinking Middle Class

YouTube Video; Is America Dreaming?: Understanding Social Mobility (by the Brookings Institution)

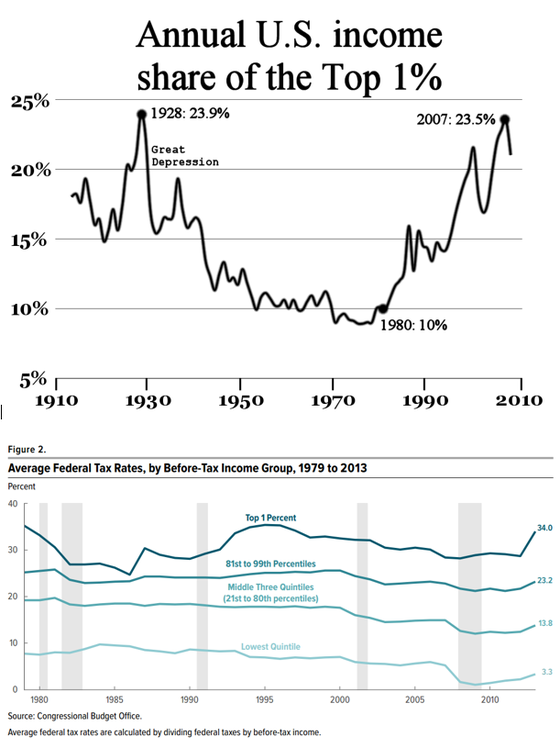

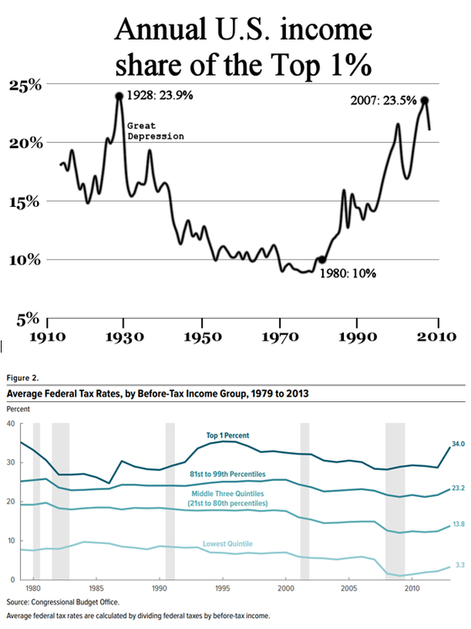

Pictured Below:

TOP CHART: “Annual U.S. Income share of the Top 1% Income Earners”

BOTTOM CHART: Distribution of US federal taxes from 1979 to 2013, based on CBO Estimates. (Courtesy of US Congressional Budget Office, publication 44604)

YouTube Video; Is America Dreaming?: Understanding Social Mobility (by the Brookings Institution)

Pictured Below:

TOP CHART: “Annual U.S. Income share of the Top 1% Income Earners”

BOTTOM CHART: Distribution of US federal taxes from 1979 to 2013, based on CBO Estimates. (Courtesy of US Congressional Budget Office, publication 44604)

As Reported By PEW Research Center (12/9/2015): "No longer the majority and falling behind financially"

"After more than four decades of serving as the nation’s economic majority, the American middle class is now matched in number by those in the economic tiers above and below it. In early 2015, 120.8 million adults were in middle-income households, compared with 121.3 million in lower- and upper-income households combined, a demographic shift that could signal a tipping point, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data..."

Click here for more from the PEW Research Center: "The American Middle Class Is Losing Ground"

Causes of income inequality in the United States describes why changes in the country's income distribution are occurring. This topic is subject to extensive ongoing research, media attention, and political interest, as it involves how the national income of the country is split among its people at various income levels.

Overview:

Income inequality in the United States has grown significantly since the early 1970s, after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions. The U.S. consistently exhibits higher rates of income inequality than most developed nations, arguably due to the nation's relatively enhanced support of free market capitalism.

According to the CBO and others, "the precise reasons for the [recent] rapid growth in income at the top are not well understood", but "in all likelihood," an "interaction of multiple factors" was involved. "Researchers have offered several potential rationales."[16][19] Some of these rationales conflict, some overlap. They include:

Paul Krugman put several of these factors into context in January 2015: "Competition from emerging-economy exports has surely been a factor depressing wages in wealthier nations, although probably not the dominant force.

More important, soaring incomes at the top were achieved, in large part, by squeezing those below: by cutting wages, slashing benefits, crushing unions, and diverting a rising share of national resources to financial wheeling and dealing...Perhaps more important still, the wealthy exert a vastly disproportionate effect on policy. And elite priorities — obsessive concern with budget deficits, with the supposed need to slash social programs — have done a lot to deepen (wage stagnation and income inequality)"

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Causes of Income Inequality:

"After more than four decades of serving as the nation’s economic majority, the American middle class is now matched in number by those in the economic tiers above and below it. In early 2015, 120.8 million adults were in middle-income households, compared with 121.3 million in lower- and upper-income households combined, a demographic shift that could signal a tipping point, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data..."

Click here for more from the PEW Research Center: "The American Middle Class Is Losing Ground"

Causes of income inequality in the United States describes why changes in the country's income distribution are occurring. This topic is subject to extensive ongoing research, media attention, and political interest, as it involves how the national income of the country is split among its people at various income levels.

Overview:

Income inequality in the United States has grown significantly since the early 1970s, after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions. The U.S. consistently exhibits higher rates of income inequality than most developed nations, arguably due to the nation's relatively enhanced support of free market capitalism.

According to the CBO and others, "the precise reasons for the [recent] rapid growth in income at the top are not well understood", but "in all likelihood," an "interaction of multiple factors" was involved. "Researchers have offered several potential rationales."[16][19] Some of these rationales conflict, some overlap. They include:

- the globalization hypothesis – low skilled American workers have been losing ground in the face of competition from low-wage workers in Asia and other "emerging" economies;

- skill-biased technological change – the rapid pace of progress in information technology has increased the demand for the highly skilled and educated so that income distribution favored brains rather than brawn;

- the superstar hypothesis – modern technologies of communication often turn competition into a tournament in which the winner is richly rewarded, while the runners-up get far less than in the past;

- immigration of less-educated workers – relatively high levels of immigration of low skilled workers since 1965 may have reduced wages for American-born high school dropouts;

- changing institutions and norms – Unions were a balancing force, helping ensure wages kept up with productivity and that neither executives nor shareholders were unduly rewarded. Further, societal norms placed constraints on executive pay. This changed as union power declined (the share of unionized workers fell significantly during the Great Divergence, from over 30% to around 12%) and CEO pay skyrocketed (rising from around 40 times the average workers pay in the 1970s to over 350 times in the early 2000s).

- policy, politics and race – movement conservatives increased their influence over the Republican Party beginning in the 1970s, moving it politically rightward. Combined with the Party's expanded political power (enabled by a shift of southern white Democrats to the Republican Party following the passage of Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s), this resulted in more regressive tax laws, anti-labor policies, and further limited expansion of the welfare state relative to other developed nations (e.g., the unique absence of universal healthcare).

Paul Krugman put several of these factors into context in January 2015: "Competition from emerging-economy exports has surely been a factor depressing wages in wealthier nations, although probably not the dominant force.

More important, soaring incomes at the top were achieved, in large part, by squeezing those below: by cutting wages, slashing benefits, crushing unions, and diverting a rising share of national resources to financial wheeling and dealing...Perhaps more important still, the wealthy exert a vastly disproportionate effect on policy. And elite priorities — obsessive concern with budget deficits, with the supposed need to slash social programs — have done a lot to deepen (wage stagnation and income inequality)"

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Causes of Income Inequality:

Income Inequality in the United States

YouTube Video: U.S. Income Equality Keeps Getting Worse*

*-CNN article excerpted in text below Picture:

From CNN, 12/22/16 by Heather Long

"Inequality in America is getting uglier."

"The gap between the "haves" and "have nots" is widening, according to the latest data out this week.

The rich are money-making machines. Today, the top mega wealthy -- the top 1% -- earn an average of $1.3 million a year. It's more than three times as much as the 1980s, when the rich "only" made $428,000, on average, according to economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman.

Meanwhile, the bottom 50% of the American population earned an average of $16,000 in pre-tax income in 1980. That hasn't changed in over three decades.

As if that's not depressing enough, living the American Dream is also getting harder to do.

Millennials, born in the 1980s, only have a 50% likelihood -- a coin toss chance -- of earning more money than their parents did, according to new research released this month from the Equality of Opportunity Project.

It wasn't always this way. In the 1940s, almost everyone in America grew up to be better off financially than their parents. While money isn't the only definition of success, more wealth typically leads to bigger houses, grander vacations, fancier cars and more opportunities to advance.

Children's prospects of achieving the 'American Dream' of earning more than their parents have fallen from 90% to 50% over the past half century," the researchers wrote in their report." : Click here for fully article.

___________________________________________________________________________

Income inequality in the United States has increased significantly since the 1970s after several decades of stability, meaning the share of the nation's income received by higher income households has increased.

This trend is evident with income measured both before taxes (market income) as well as after taxes and transfer payments. Income inequality has fluctuated considerably since measurements began around 1915, moving in an arc between peaks in the 1920s and 2000s, with a 30-year period of relatively lower inequality between 1950–1980.

Measured for all households, U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed countries before taxes and transfers, but is among the highest after taxes and transfers, meaning the U.S. shifts relatively less income from higher income households to lower income households.

Measured for working-age households, market income inequality is comparatively high (rather than moderate) and the level of redistribution is moderate (not low). These comparisons indicate Americans shift from reliance on market income to reliance on income transfers later in life and less than households in other developed countries do.

The U.S. ranks around the 30th percentile in income inequality globally, meaning 70% of countries have a more equal income distribution. U.S. federal tax and transfer policies are progressive and therefore reduce income inequality measured after taxes and transfers. Tax and transfer policies together reduced income inequality slightly more in 2011 than in 1979.

While there is strong evidence that it has increased since the 1970s, there is active debate in the United States regarding the appropriate measurement, causes, effects and solutions to income inequality.

The two major political parties have different approaches to the issue, with Democrats historically emphasizing that economic growth should result in shared prosperity (i.e., a pro-labor argument advocating income redistribution), while Republicans tend to downplay the validity or feasibility of positively influencing the issue (i.e., a pro-capital argument against redistribution).

Overview:

U.S. income inequality has grown significantly since the early 1970s, after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions. The U.S. consistently exhibits higher rates of income inequality than most developed nations due to the nation's enhanced support of free market capitalism and less progressive spending on social services.

The top 1% of income earners received approximately 20% of the pre-tax income in 2013, versus approximately 10% from 1950 to 1980. The top 1% is not homogeneous, with the very top income households pulling away from others in the top 1%. For example, the top 0.1% of households received approximately 10% of the pre-tax income in 2013, versus approximately 3–4% between 1951–1981.

According to IRS data, adjusted gross income (AGI) of approximately $430,000 was required to be in the top 1% in 2013.

Most of the growth in income inequality has been between the middle class and top earners, with the disparity widening the further one goes up in the income distribution. The bottom 50% earned 20% of the nation's pre-tax income in 1979; this fell steadily to 14% by 2007 and 13% by 2014. Income for the middle 40% group, a proxy for the middle class, fell from 45% in 1979 to 41% in both 2007 and 2014.

To put this change into perspective, if the US had the same income distribution it had in 1979, each family in the bottom 80% of the income distribution would have $11,000 more per year in income on average, or $916 per month. Half of the U.S. population lives in poverty or is low-income, according to U.S. Census data.

The trend of rising income inequality is also apparent after taxes and transfers. A 2011 study by the CBO found that the top earning 1 percent of households increased their income by about 275% after federal taxes and income transfers over a period between 1979 and 2007, compared to a gain of just under 40% for the 60 percent in the middle of America's income distribution.

U.S. federal tax and transfer policies are progressive and therefore substantially reduce income inequality measured after taxes and transfers. They became moderately less progressive between 1979 and 2007, but slightly more progressive measured between 1979 and 2011. Income transfers had a greater impact on reducing inequality than taxes from 1979 to 2011.

Americans are not generally aware of the extent of inequality or recent trends. There is a direct relationship between actual income inequality and the public's views about the need to address the issue in most developed countries, but not in the U.S., where income inequality is worse but the concern is lower.

The U.S. was ranked the 6th worst among 173 countries (4th percentile) on income equality measured by the Gini index.

There is significant and ongoing debate as to the causes, economic effects, and solutions regarding income inequality. While before-tax income inequality is subject to market factors (e.g., globalization, trade policy, labor policy, and international competition), after-tax income inequality can be directly affected by tax and transfer policy. U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed nations before taxes and transfers, but is among the worst after taxes and transfers. Income inequality may contribute to slower economic growth, reduced income mobility, higher levels of household debt, and greater risk of financial crises and deflation.

Labor (workers) and capital (owners) have always battled over the share of the economic pie each obtains. The influence of the labor movement has waned in the U.S. since the 1960s along with union participation and more pro-capital laws. The share of total worker compensation has declined from 58% of national income (GDP) in 1970 to nearly 53% in 2013, contributing to income inequality. This has led to concerns that the economy has shifted too far in favor of capital, via a form of corporatism, corpocracy or neoliberalism.

Although some have spoken out in favor of moderate inequality as a form of incentive, others have warned against the current high levels of inequality, including Yale Nobel prize for economics winner Robert J. Shiller, (who called rising economic inequality "the most important problem that we are facing now today"), former Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan, ("This is not the type of thing which a democratic society – a capitalist democratic society – can really accept without addressing"), and President Barack Obama (who referred to the widening income gap as the "defining challenge of our time").

after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions.

For more about Income Inequality in the United States, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

"Inequality in America is getting uglier."

"The gap between the "haves" and "have nots" is widening, according to the latest data out this week.

The rich are money-making machines. Today, the top mega wealthy -- the top 1% -- earn an average of $1.3 million a year. It's more than three times as much as the 1980s, when the rich "only" made $428,000, on average, according to economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman.

Meanwhile, the bottom 50% of the American population earned an average of $16,000 in pre-tax income in 1980. That hasn't changed in over three decades.

As if that's not depressing enough, living the American Dream is also getting harder to do.

Millennials, born in the 1980s, only have a 50% likelihood -- a coin toss chance -- of earning more money than their parents did, according to new research released this month from the Equality of Opportunity Project.

It wasn't always this way. In the 1940s, almost everyone in America grew up to be better off financially than their parents. While money isn't the only definition of success, more wealth typically leads to bigger houses, grander vacations, fancier cars and more opportunities to advance.

Children's prospects of achieving the 'American Dream' of earning more than their parents have fallen from 90% to 50% over the past half century," the researchers wrote in their report." : Click here for fully article.

___________________________________________________________________________

Income inequality in the United States has increased significantly since the 1970s after several decades of stability, meaning the share of the nation's income received by higher income households has increased.

This trend is evident with income measured both before taxes (market income) as well as after taxes and transfer payments. Income inequality has fluctuated considerably since measurements began around 1915, moving in an arc between peaks in the 1920s and 2000s, with a 30-year period of relatively lower inequality between 1950–1980.

Measured for all households, U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed countries before taxes and transfers, but is among the highest after taxes and transfers, meaning the U.S. shifts relatively less income from higher income households to lower income households.

Measured for working-age households, market income inequality is comparatively high (rather than moderate) and the level of redistribution is moderate (not low). These comparisons indicate Americans shift from reliance on market income to reliance on income transfers later in life and less than households in other developed countries do.

The U.S. ranks around the 30th percentile in income inequality globally, meaning 70% of countries have a more equal income distribution. U.S. federal tax and transfer policies are progressive and therefore reduce income inequality measured after taxes and transfers. Tax and transfer policies together reduced income inequality slightly more in 2011 than in 1979.

While there is strong evidence that it has increased since the 1970s, there is active debate in the United States regarding the appropriate measurement, causes, effects and solutions to income inequality.

The two major political parties have different approaches to the issue, with Democrats historically emphasizing that economic growth should result in shared prosperity (i.e., a pro-labor argument advocating income redistribution), while Republicans tend to downplay the validity or feasibility of positively influencing the issue (i.e., a pro-capital argument against redistribution).

Overview:

U.S. income inequality has grown significantly since the early 1970s, after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions. The U.S. consistently exhibits higher rates of income inequality than most developed nations due to the nation's enhanced support of free market capitalism and less progressive spending on social services.

The top 1% of income earners received approximately 20% of the pre-tax income in 2013, versus approximately 10% from 1950 to 1980. The top 1% is not homogeneous, with the very top income households pulling away from others in the top 1%. For example, the top 0.1% of households received approximately 10% of the pre-tax income in 2013, versus approximately 3–4% between 1951–1981.

According to IRS data, adjusted gross income (AGI) of approximately $430,000 was required to be in the top 1% in 2013.

Most of the growth in income inequality has been between the middle class and top earners, with the disparity widening the further one goes up in the income distribution. The bottom 50% earned 20% of the nation's pre-tax income in 1979; this fell steadily to 14% by 2007 and 13% by 2014. Income for the middle 40% group, a proxy for the middle class, fell from 45% in 1979 to 41% in both 2007 and 2014.

To put this change into perspective, if the US had the same income distribution it had in 1979, each family in the bottom 80% of the income distribution would have $11,000 more per year in income on average, or $916 per month. Half of the U.S. population lives in poverty or is low-income, according to U.S. Census data.

The trend of rising income inequality is also apparent after taxes and transfers. A 2011 study by the CBO found that the top earning 1 percent of households increased their income by about 275% after federal taxes and income transfers over a period between 1979 and 2007, compared to a gain of just under 40% for the 60 percent in the middle of America's income distribution.

U.S. federal tax and transfer policies are progressive and therefore substantially reduce income inequality measured after taxes and transfers. They became moderately less progressive between 1979 and 2007, but slightly more progressive measured between 1979 and 2011. Income transfers had a greater impact on reducing inequality than taxes from 1979 to 2011.

Americans are not generally aware of the extent of inequality or recent trends. There is a direct relationship between actual income inequality and the public's views about the need to address the issue in most developed countries, but not in the U.S., where income inequality is worse but the concern is lower.

The U.S. was ranked the 6th worst among 173 countries (4th percentile) on income equality measured by the Gini index.

There is significant and ongoing debate as to the causes, economic effects, and solutions regarding income inequality. While before-tax income inequality is subject to market factors (e.g., globalization, trade policy, labor policy, and international competition), after-tax income inequality can be directly affected by tax and transfer policy. U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed nations before taxes and transfers, but is among the worst after taxes and transfers. Income inequality may contribute to slower economic growth, reduced income mobility, higher levels of household debt, and greater risk of financial crises and deflation.

Labor (workers) and capital (owners) have always battled over the share of the economic pie each obtains. The influence of the labor movement has waned in the U.S. since the 1960s along with union participation and more pro-capital laws. The share of total worker compensation has declined from 58% of national income (GDP) in 1970 to nearly 53% in 2013, contributing to income inequality. This has led to concerns that the economy has shifted too far in favor of capital, via a form of corporatism, corpocracy or neoliberalism.

Although some have spoken out in favor of moderate inequality as a form of incentive, others have warned against the current high levels of inequality, including Yale Nobel prize for economics winner Robert J. Shiller, (who called rising economic inequality "the most important problem that we are facing now today"), former Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan, ("This is not the type of thing which a democratic society – a capitalist democratic society – can really accept without addressing"), and President Barack Obama (who referred to the widening income gap as the "defining challenge of our time").

after several decades of stability, and has been the subject of study of many scholars and institutions.

For more about Income Inequality in the United States, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

- History

- Causes

- Effects: Economic

- Effects: Socio-economic mobility

- Effects on democracy and society

- Public attitudes

- States and cities

- International comparisons

- Policy responses

- Overview

- Resources available to children

- Affordable higher education

- Public welfare and infrastructure spending

- Taxes on the wealthy

- Reduce tax expenditures

- Corporate tax reform

- Minimum wages

- Maximum wage implementation

- Subsidies and income guarantees

- Rent-seeking limits

- Economic democracy

- Monetary policy

- Measurement approaches

- Wealth inequality

- See also:

- American Dream

- Economic inequality

- Economic mobility

- Economy of the United States

- Educational attainment in the United States

- High-net-worth individual

- Homelessness in the United States

- Inequality for All – 2013 documentary film presented by Robert Reich

- Income inequality metrics

- Legatum Prosperity Index

- List of countries by income equality

- List of countries by inequality-adjusted HDI

- Median income per household member

- Middle-class squeeze

- Occupy Movement

- Racial inequality in the United States

- Second Bill of Rights

- Socio-economic mobility in the United States

- The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap – book

- The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better – book

- Social justice

- Tax policy and economic inequality in the United States

Widening Gap in Income between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of Americans

YouTube Video by Robert Reich*: "Inequality for All"

* -- Robert Reich, Chancellor's Professor of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley; Former Secretary of Labor

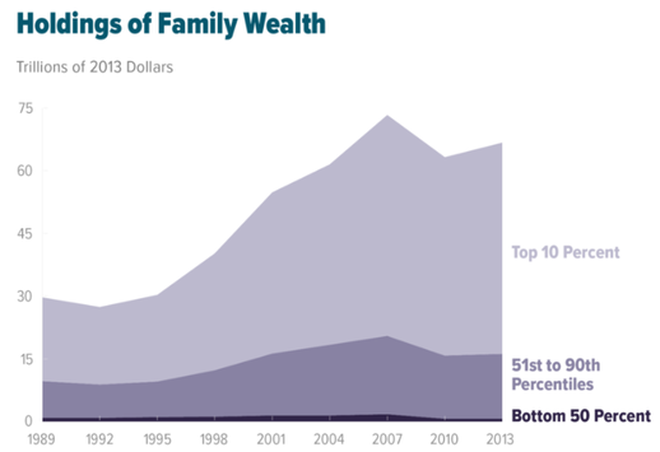

Pictured: CBO Chart, U.S. Holdings of Family Wealth 1989 to 2013. The top 10% of families held 76% of the wealth in 2013, while the bottom 50% of families held 1%. Inequality worsened from 1989 to 2013.

Wealth inequality in the United States (also known as the wealth gap) is the unequal distribution of assets among residents of the United States.

Wealth includes the values of homes, automobiles, personal valuables, businesses, savings, and investments.

However, according to the federal reserve, "For most households, pensions and Social Security are the most important sources of income during retirement, and the promised benefit stream constitutes a sizable fraction of household wealth" and "including pensions and Social Security in net worth makes the distribution more even".

Just prior to President Obama's 2014 State of the Union Address, media reported that the top wealthiest 1% possess 40% of the nation’s wealth; the bottom 80% own 7%; similarly, but later, the media reported, the "richest 1 percent in the United States now own more additional income than the bottom 90 percent".

The gap between the top 10% and the middle class is over 1,000%; that increases another 1,000% for the top 1%. The average employee "needs to work more than a month to earn what the CEO earns in one hour." Although different from income inequality, the two are related.

In Inequality for All—a 2013 documentary with Robert Reich in which he argued that income inequality is the defining issue for the United States—Reich states that 95% of economic gains went to the top 1% net worth (HNWI) since 2009 when the recovery allegedly started.

More recently, in 2017, an Oxfam study found that eight rich people, six of them Americans, own as much combined wealth as "half the human race".

A 2011 study found that US citizens across the political spectrum dramatically underestimate the current US wealth inequality and would prefer a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth.

Wealth is usually not used for daily expenditures or factored into household budgets, but combined with income it comprises the family's total opportunity "to secure a desired stature and standard of living, or pass their class status along to one's children".

Moreover, "wealth provides for both short- and long-term financial security, bestows social prestige, and contributes to political power, and can be used to produce more wealth."

Hence, wealth possesses a psychological element that awards people the feeling of agency, or the ability to act. The accumulation of wealth grants more options and eliminates restrictions about how one can live life. Dennis Gilbert asserts that the standard of living of the working and middle classes is dependent upon income and wages, while the rich tend to rely on wealth, distinguishing them from the vast majority of Americans.

A September 2014 study by Harvard Business School declared that the growing disparity between the very wealthy and the lower and middle classes is no longer sustainable.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Wealth Inequality in the United States:

Wealth includes the values of homes, automobiles, personal valuables, businesses, savings, and investments.

However, according to the federal reserve, "For most households, pensions and Social Security are the most important sources of income during retirement, and the promised benefit stream constitutes a sizable fraction of household wealth" and "including pensions and Social Security in net worth makes the distribution more even".

Just prior to President Obama's 2014 State of the Union Address, media reported that the top wealthiest 1% possess 40% of the nation’s wealth; the bottom 80% own 7%; similarly, but later, the media reported, the "richest 1 percent in the United States now own more additional income than the bottom 90 percent".

The gap between the top 10% and the middle class is over 1,000%; that increases another 1,000% for the top 1%. The average employee "needs to work more than a month to earn what the CEO earns in one hour." Although different from income inequality, the two are related.

In Inequality for All—a 2013 documentary with Robert Reich in which he argued that income inequality is the defining issue for the United States—Reich states that 95% of economic gains went to the top 1% net worth (HNWI) since 2009 when the recovery allegedly started.

More recently, in 2017, an Oxfam study found that eight rich people, six of them Americans, own as much combined wealth as "half the human race".

A 2011 study found that US citizens across the political spectrum dramatically underestimate the current US wealth inequality and would prefer a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth.

Wealth is usually not used for daily expenditures or factored into household budgets, but combined with income it comprises the family's total opportunity "to secure a desired stature and standard of living, or pass their class status along to one's children".

Moreover, "wealth provides for both short- and long-term financial security, bestows social prestige, and contributes to political power, and can be used to produce more wealth."

Hence, wealth possesses a psychological element that awards people the feeling of agency, or the ability to act. The accumulation of wealth grants more options and eliminates restrictions about how one can live life. Dennis Gilbert asserts that the standard of living of the working and middle classes is dependent upon income and wages, while the rich tend to rely on wealth, distinguishing them from the vast majority of Americans.

A September 2014 study by Harvard Business School declared that the growing disparity between the very wealthy and the lower and middle classes is no longer sustainable.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Wealth Inequality in the United States:

- Statistics

- Wealth and income

- Wealth inequality and child poverty

- Causes of wealth inequality

- Racial disparities

- Effect on democracy

- See also:

- Affluence in the United States

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

- Donor Class

- Monetary policy

- Net worth

- "Occupy" protests

- Occupy Wall Street

- Oligarchy

- Plutocracy

- Pareto principle

- Power elite

- Redistribution of wealth

- Tax Policy and Economic Inequality in the United States

- The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap

- Wealth concentration

- Wealth in the United States

- We are the 99%

Economic Globalization

YouTube: The Link Between Globalization and Political Instability

(Video by Stanford Graduate School of Business)

Pictured below: The Impact of Globalization On Economic Growth (See below)

The Impact of Globalization On Economic Growth by The Balance

Globalization has impacted nearly every aspect of modern life. While some U.S. citizens may not be able to locate Beijing, China on a map, they certainly purchase an overwhelming number of goods that were manufactured there.

According to a 2010 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco report, approximately 35.6 percent of all clothing and shoes sold in the United States were actually manufactured in China, compared to just 3.4 percent made domestically. Below is a look beyond the everyday implications of globalization and towards the economic implications that impact international investors.

Globalization Benefits World Economies:

Most economists agree that globalization provides a net benefit to individual economies around the world, by making markets more efficient, increasing competition, limiting military conflicts, and spreading wealth more equally around the world.

However, the general public tends to assume that the costs associated with globalization outweigh the benefits, especially in the short-term, which has caused problems we’ll explore in the next section on protectionism.

The Milken Institute’s Globalization of the World Economy report highlights many of the benefits associated with globalization while outlining some of the associated risks that governments and investors should consider.

But, in aggregate, there is a consensus among economists that globalization provides a net benefit to nations around the world and therefore should be embraced on the whole by governments and individuals.

Some of the benefits of globalization include:

Some of the risks of globalization include:

Tariffs & Other Forms of Protectionism:

The 2008 economic crisis led many politicians to question the merits of globalization. Since then, global capital flows fell from $11 trillion in 2007 to a third of that figure in 2012. While some of that may be cyclical in nature, many countries implemented tariffs and other forms of protectionism designed to contain risk in their financial systems and make crises less damaging, although this comes at the cost of forgoing the benefits we’ve seen.

In the U.S. and Europe, new banking regulations were introduced that limited capital flows in order to reduce the risk of contagion. Tariffs have also been put in place to protect domestic industries seen as vital, such as the 127% U.S. tariff on Chinese paper clips or Japan’s 778% tariff on imported rice.

In developing countries, these figures are even worse, with Brazil’s tariffs being some four times higher than America’s and three times higher than China’s.

The election of Donald Trump in the United States and the British vote to leave the European Union - known as the 'Brexit' - have also contributed to the anti-globalization movement.

These trends have been driven by anti-immigration sentiments in Europe, although elections occurring in the past year have proven to be largely pro-globalization rather than anti-globalization.

Globalization may be inevitable over the long-run, but there are many bumps along the road in the short-run. These bumps are often spurred by economic crises or some of the negative consequences of globalization, but in the end, the world has always managed to learn that protectionism can make a bad situation worse.

The Bottom Line:

Globalization has impacted nearly every aspect of modern life and continues to be a growing force in the global economy. While there are a few drawbacks to globalization, most economists agree that it's a force that's both unstoppable and net beneficial to the world economy.

There have always been periods of protectionism and nationalism in the past, but globalization continues to be the most widely accepted solution to ensuring consistent economic growth around the world.

[End of Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

Economic globalization is one of the three main dimensions of globalization commonly found in academic literature, with the two others being political globalization and cultural globalization, as well as the general term of globalization.

Economic globalization refers to the free movement of goods, capital, services, technology and information. It is the increasing economic integration and interdependence of national, regional, and local economies across the world through an intensification of cross-border movement of goods, services, technologies and capital.

Whereas globalization is a broad set of processes concerning multiple networks of economic, political, and cultural interchange, contemporary economic globalization is propelled by the rapid growing significance of information in all types of productive activities and marketization, and by developments in science and technology.

Economic globalization primarily comprises the globalization of production, finance, markets, technology, organizational regimes, institutions, corporations, and labor.

While economic globalization has been expanding since the emergence of trans-national trade, it has grown at an increased rate due to an increase in communication and technological advances under the framework of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and World Trade Organization, which made countries gradually cut down trade barriers and open up their current accounts and capital accounts.

This recent boom has been largely supported by developed economies integrating with majority world through foreign direct investment and lowering costs of doing business, the reduction of trade barriers, and in many cases cross border migration

While globalization has radically increased incomes and economic growth in developing countries and lowered consumer prices in developed countries, it also changes the power balance between developing and developed countries and affects the culture of each affected country.

And the shifting location of goods production has caused many jobs to cross borders, requiring some workers in developed countries to change careers.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Economic Globalization:

Globalization has impacted nearly every aspect of modern life. While some U.S. citizens may not be able to locate Beijing, China on a map, they certainly purchase an overwhelming number of goods that were manufactured there.

According to a 2010 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco report, approximately 35.6 percent of all clothing and shoes sold in the United States were actually manufactured in China, compared to just 3.4 percent made domestically. Below is a look beyond the everyday implications of globalization and towards the economic implications that impact international investors.

Globalization Benefits World Economies:

Most economists agree that globalization provides a net benefit to individual economies around the world, by making markets more efficient, increasing competition, limiting military conflicts, and spreading wealth more equally around the world.

However, the general public tends to assume that the costs associated with globalization outweigh the benefits, especially in the short-term, which has caused problems we’ll explore in the next section on protectionism.

The Milken Institute’s Globalization of the World Economy report highlights many of the benefits associated with globalization while outlining some of the associated risks that governments and investors should consider.

But, in aggregate, there is a consensus among economists that globalization provides a net benefit to nations around the world and therefore should be embraced on the whole by governments and individuals.

Some of the benefits of globalization include:

- Foreign Direct Investment. Foreign direct investment (“FDI”) tends to increase at a much greater rate than the growth in world trade, helping boost technology transfer, industrial restructuring, and the growth of global companies.

- Technological Innovation. Increased competition from globalization helps stimulate new technology development, particularly with the growth in FDI, which helps improve economic output by making processes more efficient.

- Economies of Scale. Globalization enables large companies to realize economies of scale that reduce costs and prices, which in turn supports further economic growth, although this can hurt many small businesses attempting to compete domestically.

Some of the risks of globalization include:

- Interdependence. Globalization leads to the interdependence between nations, which could cause regional or global instabilities if local economic fluctuations end up impacting a large number of countries relying on them.

- National Sovereignty. Some see the rise of nation-states, multinational or global firms and other international organizations as a threat to sovereignty. Ultimately, this could cause some leaders to become nationalistic or xenophobic.

- Equity Distribution. The benefits of globalization can be unfairly skewed towards rich nations or individuals, creating greater inequalities and leading to potential conflicts both nationally and internationally as a result.

Tariffs & Other Forms of Protectionism:

The 2008 economic crisis led many politicians to question the merits of globalization. Since then, global capital flows fell from $11 trillion in 2007 to a third of that figure in 2012. While some of that may be cyclical in nature, many countries implemented tariffs and other forms of protectionism designed to contain risk in their financial systems and make crises less damaging, although this comes at the cost of forgoing the benefits we’ve seen.

In the U.S. and Europe, new banking regulations were introduced that limited capital flows in order to reduce the risk of contagion. Tariffs have also been put in place to protect domestic industries seen as vital, such as the 127% U.S. tariff on Chinese paper clips or Japan’s 778% tariff on imported rice.

In developing countries, these figures are even worse, with Brazil’s tariffs being some four times higher than America’s and three times higher than China’s.

The election of Donald Trump in the United States and the British vote to leave the European Union - known as the 'Brexit' - have also contributed to the anti-globalization movement.

These trends have been driven by anti-immigration sentiments in Europe, although elections occurring in the past year have proven to be largely pro-globalization rather than anti-globalization.

Globalization may be inevitable over the long-run, but there are many bumps along the road in the short-run. These bumps are often spurred by economic crises or some of the negative consequences of globalization, but in the end, the world has always managed to learn that protectionism can make a bad situation worse.

The Bottom Line:

Globalization has impacted nearly every aspect of modern life and continues to be a growing force in the global economy. While there are a few drawbacks to globalization, most economists agree that it's a force that's both unstoppable and net beneficial to the world economy.

There have always been periods of protectionism and nationalism in the past, but globalization continues to be the most widely accepted solution to ensuring consistent economic growth around the world.

[End of Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

Economic globalization is one of the three main dimensions of globalization commonly found in academic literature, with the two others being political globalization and cultural globalization, as well as the general term of globalization.

Economic globalization refers to the free movement of goods, capital, services, technology and information. It is the increasing economic integration and interdependence of national, regional, and local economies across the world through an intensification of cross-border movement of goods, services, technologies and capital.

Whereas globalization is a broad set of processes concerning multiple networks of economic, political, and cultural interchange, contemporary economic globalization is propelled by the rapid growing significance of information in all types of productive activities and marketization, and by developments in science and technology.

Economic globalization primarily comprises the globalization of production, finance, markets, technology, organizational regimes, institutions, corporations, and labor.

While economic globalization has been expanding since the emergence of trans-national trade, it has grown at an increased rate due to an increase in communication and technological advances under the framework of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and World Trade Organization, which made countries gradually cut down trade barriers and open up their current accounts and capital accounts.

This recent boom has been largely supported by developed economies integrating with majority world through foreign direct investment and lowering costs of doing business, the reduction of trade barriers, and in many cases cross border migration