Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Our Free Press

Covers the Media in the United States as protected by the First Amendment, whether broadcast, cable, Internet or in Print.

See Also:

Politics in the United States

Democracy in the USA

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

YouTube Video: President Trump's "fake news" claims create real danger by Anderson Cooper, CNN

Pictured: Top: Tweet from Donald Trump attacking the Free Press; Bottom: Five benefits of the First Amendment including (L-R) Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Religion, Freedom of Assembly and Free to Petition

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Congress from making any law respecting an establishment of religion, prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the right to peaceably assemble, or to petition for a governmental redress of grievances.

The first amendment was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights was originally proposed to assuage Anti-Federalist opposition to Constitutional ratification. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by the Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today.

Beginning with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court applied the First Amendment to states—a process known as incorporation—through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court drew on Thomas Jefferson's correspondence to call for "a wall of separation between church and State", though the precise boundary of this separation remains in dispute. Speech rights were expanded significantly in a series of 20th and 21st-century court decisions which protected various forms of political speech, anonymous speech, campaign financing, pornography, and school speech; these rulings also defined a series of exceptions to First Amendment protections.

The Supreme Court overturned English common law precedent to increase the burden of proof for defamation and libel suits, most notably in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). Commercial speech, however, is less protected by the First Amendment than political speech, and is therefore subject to greater regulation.

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In Near v. Minnesota (1931) and New York Times v. United States (1971), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected against prior restraint—pre-publication censorship—in almost all cases. The Petition Clause protects the right to petition all branches and agencies of government for action. In addition to the right of assembly guaranteed by this clause, the Court has also ruled that the amendment implicitly protects freedom of association.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the First Amendment to the United States Constitution:

The first amendment was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights was originally proposed to assuage Anti-Federalist opposition to Constitutional ratification. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by the Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today.

Beginning with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court applied the First Amendment to states—a process known as incorporation—through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court drew on Thomas Jefferson's correspondence to call for "a wall of separation between church and State", though the precise boundary of this separation remains in dispute. Speech rights were expanded significantly in a series of 20th and 21st-century court decisions which protected various forms of political speech, anonymous speech, campaign financing, pornography, and school speech; these rulings also defined a series of exceptions to First Amendment protections.

The Supreme Court overturned English common law precedent to increase the burden of proof for defamation and libel suits, most notably in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). Commercial speech, however, is less protected by the First Amendment than political speech, and is therefore subject to greater regulation.

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In Near v. Minnesota (1931) and New York Times v. United States (1971), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected against prior restraint—pre-publication censorship—in almost all cases. The Petition Clause protects the right to petition all branches and agencies of government for action. In addition to the right of assembly guaranteed by this clause, the Court has also ruled that the amendment implicitly protects freedom of association.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the First Amendment to the United States Constitution:

- Text

- Background

- Establishment of religion

- Free exercise of religion

- Freedom of speech and of the press

- Petition and assembly

- Freedom of association

- See also:

- Censorship in the United States

- Freedom of thought

- Free speech zones

- Government speech

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution

- List of United States Supreme Court cases involving the First Amendment

- Marketplace of ideas

- Military expression

- Photography is Not a Crime

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

- Cornell Law School – Annotated Constitution

- First Amendment Center – The First Amendment Library

- Cohen, Henry (October 16, 2009). "Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment" (PDF). Legislative Attorney. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

Freedom of the Press in the United States

YouTube Video of the Movie Trailer "The Post" (2018)

Pictured: a Modern Newspaper Printing Press

Freedom of the press in the United States is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment is generally understood to prevent the government from interfering with the distribution of information and opinions.

Nevertheless, freedom of the press is subject to certain restrictions, such as defamation law.

Ranking of the Freedom of the United States compared to other nations:

Freedom House, an independent watchdog organization, ranked the United States 30th out of 197 countries in press freedom in 2014. Its report praised the constitutional protections given American journalists and criticized authorities for placing undue limits on investigative reporting in the name of national security.

Freedom House gives countries a score out of 100, with 0 the most free and 100 the least free. The score is broken down into three separately-weighted categories: legal (out of 30), political (out of 40) and economic (out of 30). The United States scored 6, 10, and 5, respectively, that year for a cumulative score of 21.

In 2014, the U.S. ranked 46th in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. This is a measure of freedom available to the press, which encompasses areas such as government censorship and is not indicative of journalistic quality. Its ranking fell from 20th in 2010 to 42nd in 2012, which was attributed to arrests of journalists covering the Occupy movement.

The U.S. ranked 49th in 2015 and 41st in 2016.

In 2012, Finland and Norway tied for first place worldwide. Canada ranked 10th, Germany tied with Jamaica for 17th and Japan tied with Suriname for 22nd. The UK ranked 28th, Australia 30th and France 38th. Extraterritorial regions of the U.S. ranked 57th.

Notable Exceptions:

In 1798, shortly after the adoption of the Constitution, the governing Federalist Party attempted to stifle criticism with the Alien and Sedition Acts. According to the Sedition Act, criticism of Congress or the President (but not the Vice-President) was a crime; Thomas Jefferson—a non-Federalist—was Vice-President when the act was passed. These restrictions on the press were very unpopular, leading to the party's eventual demise.

Jefferson, who vehemently opposed the acts, was elected president in 1800 and pardoned most of those convicted under them. In his March 4, 1801 inaugural address, he reiterated his longstanding commitment to freedom of speech and of the press: "If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it."

In mid-August 1861, four New York City newspapers (the New York Daily News, The Journal of Commerce, the Day Book and the New York Freeman’s Journal) were given a presentment by a U.S. Circuit Court grand jury for "frequently encouraging the rebels by expressions of sympathy and agreement".

This began a series of federal prosecutions during the Civil War of northern U.S. newspapers which expressed sympathy for Southern causes or criticized the Lincoln administration. Lists of "peace newspapers", published in protest by the New York Daily News, were used to plan retributions. The Bangor Democrat in Maine, was one of these newspapers; assailants believed part of a covert Federal raid destroyed the press and set the building ablaze.

These actions followed executive orders issued by President Abraham Lincoln; his August 7, 1861 order made it illegal (punishable by death) to conduct "correspondence with" or give "intelligence to the enemy, either directly or indirectly".

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which amended it, imposed restrictions on the press during wartime. The acts imposed a fine of $10,000 and up to 20 years' imprisonment for those publishing "... disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States, or the flag ..."

In Schenck v. United States (1919) the Supreme Court upheld the laws, setting the "clear and present danger" standard. Congress repealed both laws in 1921, and Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) revised the clear-and-present-danger test to the significantly less-restrictive "imminent lawless action" test.

In Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court upheld the right of a school principal to review (and suppress) controversial articles in a school newspaper funded by the school and published in its name.

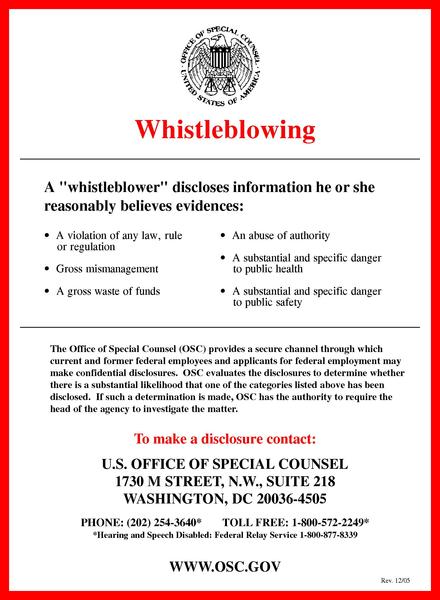

In United States v. Manning (2013), Chelsea Manning was found guilty of six counts of espionage for furnishing classified information to Wikileaks.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Freedom of the Press:

Nevertheless, freedom of the press is subject to certain restrictions, such as defamation law.

Ranking of the Freedom of the United States compared to other nations:

Freedom House, an independent watchdog organization, ranked the United States 30th out of 197 countries in press freedom in 2014. Its report praised the constitutional protections given American journalists and criticized authorities for placing undue limits on investigative reporting in the name of national security.

Freedom House gives countries a score out of 100, with 0 the most free and 100 the least free. The score is broken down into three separately-weighted categories: legal (out of 30), political (out of 40) and economic (out of 30). The United States scored 6, 10, and 5, respectively, that year for a cumulative score of 21.

In 2014, the U.S. ranked 46th in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. This is a measure of freedom available to the press, which encompasses areas such as government censorship and is not indicative of journalistic quality. Its ranking fell from 20th in 2010 to 42nd in 2012, which was attributed to arrests of journalists covering the Occupy movement.

The U.S. ranked 49th in 2015 and 41st in 2016.

In 2012, Finland and Norway tied for first place worldwide. Canada ranked 10th, Germany tied with Jamaica for 17th and Japan tied with Suriname for 22nd. The UK ranked 28th, Australia 30th and France 38th. Extraterritorial regions of the U.S. ranked 57th.

Notable Exceptions:

In 1798, shortly after the adoption of the Constitution, the governing Federalist Party attempted to stifle criticism with the Alien and Sedition Acts. According to the Sedition Act, criticism of Congress or the President (but not the Vice-President) was a crime; Thomas Jefferson—a non-Federalist—was Vice-President when the act was passed. These restrictions on the press were very unpopular, leading to the party's eventual demise.

Jefferson, who vehemently opposed the acts, was elected president in 1800 and pardoned most of those convicted under them. In his March 4, 1801 inaugural address, he reiterated his longstanding commitment to freedom of speech and of the press: "If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it."

In mid-August 1861, four New York City newspapers (the New York Daily News, The Journal of Commerce, the Day Book and the New York Freeman’s Journal) were given a presentment by a U.S. Circuit Court grand jury for "frequently encouraging the rebels by expressions of sympathy and agreement".

This began a series of federal prosecutions during the Civil War of northern U.S. newspapers which expressed sympathy for Southern causes or criticized the Lincoln administration. Lists of "peace newspapers", published in protest by the New York Daily News, were used to plan retributions. The Bangor Democrat in Maine, was one of these newspapers; assailants believed part of a covert Federal raid destroyed the press and set the building ablaze.

These actions followed executive orders issued by President Abraham Lincoln; his August 7, 1861 order made it illegal (punishable by death) to conduct "correspondence with" or give "intelligence to the enemy, either directly or indirectly".

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which amended it, imposed restrictions on the press during wartime. The acts imposed a fine of $10,000 and up to 20 years' imprisonment for those publishing "... disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States, or the flag ..."

In Schenck v. United States (1919) the Supreme Court upheld the laws, setting the "clear and present danger" standard. Congress repealed both laws in 1921, and Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) revised the clear-and-present-danger test to the significantly less-restrictive "imminent lawless action" test.

In Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court upheld the right of a school principal to review (and suppress) controversial articles in a school newspaper funded by the school and published in its name.

In United States v. Manning (2013), Chelsea Manning was found guilty of six counts of espionage for furnishing classified information to Wikileaks.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Freedom of the Press:

Media Bias in the United States

YouTube Video: The "this is fine" bias in cable news by Vox Media

Pictured: Two sources of highly reputable political coverage are (L-R) FactCheck.org and Project VoteSmart.org

Media bias in the United States occurs when the media in the United States systematically emphasizes one particular point of view in a way that contravenes the standards of professional journalism.

Claims of media bias in the United States include claims of liberal bias, conservative bias, mainstream bias, and corporate bias. To combat this, a variety of watchdog groups attempt to find the facts behind both biased reporting and unfounded claims of bias. Research about media bias is now a subject of systematic scholarship in a variety of disciplines.

Demographic polling:

A 1956 American National Election Study found that 66% of Americans thought newspapers were fair, including 78% of Republicans and 64% of Democrats.

A 1964 poll by the Roper Organization asked a similar question about network news, and 71% thought network news was fair.

A 1972 poll found that 72% of Americans trusted CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite.

According to Jonathan M. Ladd's Why Americans Hate the Media and How it Matters, "Once, institutional journalists were powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse."

That has changed. Gallup Polls since 1997 have shown that most Americans do not have confidence in the mass media "to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly". According to Gallup, the American public's trust in the media has generally declined in the first decade and a half of the 21st century.

Again according to Ladd, "In the 2008, the portion of Americans expressing 'hardly any' confidence in the press had risen to 45%. A 2004 Chronicle of Higher Education poll found that only 10% of Americans had 'a great deal' of confidence in the 'national news media,'"

In 2011, only 44% of those surveyed had "a great deal" or "a fair amount" of trust and confidence in the mass media. In 2013, a 59% majority reported a perception of media bias, with 46% saying mass media was too liberal and 13% saying it was too conservative.

The perception of bias was highest among conservatives. According to the poll, 78% of conservatives think the mass media is biased, as compared with 44% of liberals and 50% of moderates. Only about 36% view mass media reporting as "just about right".

News Values:

Main article: News values

According to Jonathan M. Ladd, Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters, "The existence of an independent, powerful, widely respected news media establishment is an historical anomaly. Prior to the twentieth century, such an institution had never existed in American history." However, he looks back to the period between 1950 and 1979 as a period where "institutional journalists were powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse."

A number of writers have tried to explain the decline in journalistic standards. One explanation is the 24-hour news cycle, which faces the necessity of generating news even when no news-worthy events occur. Another is the simple fact that bad news sells more newspapers than good news. A third possible factor is the market for "news" that reinforces the prejudices of a target audience.

"In a 2010 paper, Mr. Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, a frequent collaborator and fellow professor at Chicago Booth, found that ideological slants in newspaper coverage typically resulted from what the audience wanted to read in the media they sought out, rather than from the newspaper owners' biases."

Framing:

An important aspect of media bias is framing. A frame is the arrangement of a news story, with the goal of influencing audience to favor one side or the other. The ways in which stories are framed can greatly undermine the standards of reporting such as fairness and balance. Many media outlets are known for their outright bias. Some outlets, such as MSNBC, are known for their liberal views, while others, such as Fox News Channel, are known for their conservative views. How biased media frame stories can change audience reactions.

Corporate bias and power bias:

See also:

Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media proposed a propaganda model to explain systematic biases of U.S. media as a consequence of the pressure to create a stable and profitable business. In this view, corporate interests create five filters that bias news in their favor.

Pro-power and pro-government bias:

Part of the propaganda model is self-censorship through the corporate system (see corporate censorship); that reporters and especially editors share or acquire values that agree with corporate elites in order to further their careers. Those who do not are marginalized or fired.

Such examples have been dramatized in fact-based movie dramas such as Good Night, and Good Luck and The Insider and demonstrated in the documentary The Corporation.

George Orwell originally wrote a preface for his 1945 novel Animal Farm, which focused on the British self-censorship of the time: "The sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary. ... [Things are] kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervened but because of a general tacit agreement that 'it wouldn't do' to mention that particular fact." The preface was not published with most copies of the book.

In the propaganda model, advertising revenue is essential for funding most media sources and thus linked with media coverage. For example, according to Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR.org), 'When Al Gore proposed launching a progressive TV network, a Fox News executive told Advertising Age (10/13/03): "The problem with being associated as liberal is that they wouldn't be going in a direction that advertisers are really interested in....

If you go out and say that you are a liberal network, you are cutting your potential audience, and certainly your potential advertising pool, right off the bat." An internal memo from ABC Radio affiliates in 2006 revealed that powerful sponsors had a "standing order that their commercials never be placed on syndicated Air America programming" that aired on ABC affiliates.

The list totaled 90 advertisers and included major corporations such as Wal-Mart, GE, Exxon Mobil, Microsoft, Bank of America, FedEx, Visa, Allstate, McDonald's, Sony and Johnson & Johnson, and government entities such as the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. Navy.

According to Chomsky, U.S. commercial media encourage controversy only within a narrow range of opinion, in order to give the impression of open debate, and do not report on news that falls outside that range.

Herman and Chomsky argue that comparing the journalistic media product to the voting record of journalists is as flawed a logic as implying auto-factory workers design the cars they help produce. They concede that media owners and news makers have an agenda, but that this agenda is subordinated to corporate interests leaning to the right.

It has been argued by some critics, including historian Howard Zinn and Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges, that the corporate media routinely ignore the plight of the impoverished while painting a picture of a prosperous America.

In 2008 George W. Bush's press secretary Scott McClellan published a book in which he confessed to regularly and routinely, but unknowingly, passing on lies to the media, following the instructions of his superiors, lies that the media reported as facts. He characterized the press as, by and large, honest, and intent on telling the truth, but reported that "the national press corps was probably too deferential to the White House", especially on the subject of the war in Iraq.

FAIR reported that between January and August 2014 no representatives for organized labor made an appearance on any of the high-profile Sunday morning talkshows (NBC's Meet the Press, ABC's This Week, Fox News Sunday and CBS's Face the Nation), including episodes that covered topics such as labor rights and jobs, while current or former corporate CEOs made 12 appearances over that same period.

Corporate Control:

Six following six corporate conglomerates own the majority of mass media outlets in the United States:

Such a uniformity of ownership means that stories which are critical of these corporations may often be underplayed in the media. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 enabled this handful of corporations to expand their power, and according to Howard Zinn, such mergers "enabled tighter control of information."

Chris Hedges argues that corporate media control "of nearly everything we read, watch or hear" is an aspect of what political philosopher Sheldon Wolin calls inverted totalitarianism.

In the United States most media are operated for profit, and are usually funded by advertising. Stories critical of advertisers or their interests may be underplayed, while stories favorable to advertisers may be given more coverage.

"InfoTainment":

Main article: Infotainment

Academics such as McKay, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, and Hudson (see below) have described private U.S. media outlets as profit-driven. For the private media, profits are dependent on viewing figures, regardless of whether the viewers found the programs adequate or outstanding. The strong profit-making incentive of the American media leads them to seek a simplified format and uncontroversial position which will be adequate for the largest possible audience.

The market mechanism only rewards media outlets based on the number of viewers who watch those outlets, not by how informed the viewers are, how good the analysis is, or how impressed the viewers are by that analysis.

According to some, the profit-driven quest for high numbers of viewers, rather than high quality for viewers, has resulted in a slide from serious news and analysis to entertainment, sometimes called infotainment:

"Imitating the rhythm of sports reports, exciting live coverage of major political crises and foreign wars was now available for viewers in the safety of their own homes. By the late-1980s, this combination of information and entertainment in news programmes was known as infotainment." [Barbrook, Media Freedom, (London, Pluto Press, 1995) part 14]

Oversimplification:

Kathleen Hall Jamieson claimed in her book The Interplay of Influence: News, Advertising, Politics, and the Internet that most television news stories are made to fit into one of five categories:

Reducing news to these five categories, and tending towards an unrealistic black/white mentality, simplifies the world into easily understood opposites. According to Jamieson, the media provides an oversimplified skeleton of information that is more easily commercialized.

Media Imperialism:

Media Imperialism is a critical theory regarding the perceived effects of globalization on the world's media which is often seen as dominated by American media and culture. It is closely tied to the similar theory of cultural imperialism.

"As multinational media conglomerates grow larger and more powerful many believe that it will become increasingly difficult for small, local media outlets to survive. A new type of imperialism will thus occur, making many nations subsidiary to the media products of some of the most powerful countries or companies." Significant writers and thinkers in this area include Ben Bagdikian, Noam Chomsky, Edward S. Herman and Robert McChesney.

Conservative vs. Liberal Bias:

Conservative Bias:

Certain media outlets such as NewsMax, WorldNetDaily, and Fox News are said by critics to promote a conservative or right-wing agenda.

Rupert Murdoch, the owner and executive co-chairman of 21st Century Fox (the parent of Fox News), self-identifies as a "libertarian". Roy Greenslade of The Guardian, and others, claim that Murdoch has exerted a strong influence over the media he owns, including Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and The Sun.

According to former Fox News producer Charlie Reina, unlike the AP, CBS, or ABC, Fox News's editorial policy is set from the top down in the form of a daily memo: "[F]requently, Reina says, it also contains hints, suggestions and directives on how to slant the day's news—invariably, he said in 2003, in a way that was consistent with the politics and desires of the Bush administration." Fox News responded by denouncing Reina as a "disgruntled employee" with "an ax to grind."

According to Andrew Sullivan, "One alleged news network fed its audience a diet of lies, while contributing financially to the party that benefited from those lies."

Progressive media watchdog group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) has argued that accusations of liberal media bias are part of a conservative strategy, noting an article in the August 20, 1992 Washington Post, in which Republican party chair Rich Bond compared journalists to referees in a sporting match. "If you watch any great coach, what they try to do is 'work the refs.' Maybe the ref will cut you a little slack next time."

A 1998 study from FAIR found that journalists are "mostly centrist in their political orientation"; 30% considered themselves to the left on social issues compared with 9% on the right, while 11% considered themselves to the left on economic issues compared with 19% on the right. The report argued that since journalists considered themselves to be centrists, "perhaps this is why an earlier survey found that they tended to vote for Bill Clinton in large numbers." FAIR uses this study to support the claim that media bias is propagated down from the management, and that individual journalists are relatively neutral in their work.

A report "Examining the 'Liberal Media' Claim: Journalists Views on Politics, Economic Policy and Media Coverage" by FAIR's David Croteau, from 1998, calls into question the assumption that journalists' views are to the left of center in America. The findings were that journalists were "mostly centrist in their political orientation" and more conservative than the general public on economic issues (with a minority being more progressive than the general public on social issues).

Kenneth Tomlinson, while chairman of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, commissioned a $10,000 government study into Bill Moyers' PBS program, NOW.

The results of the study indicated that there was no particular bias on PBS. Tomlinson chose to reject the results of the study, subsequently reducing time and funding for NOW with Bill Moyers, which many including Tomlinson regarded as a "left-wing" program, and then expanded a show hosted by Fox News correspondent Tucker Carlson.

Some board members stated that his actions were politically motivated. Himself a frequent target of claims of bias (in this case, conservative bias), Tomlinson resigned from the CPB board on November 4, 2005.

Regarding the claims of a left-wing bias, Moyers asserted in a Broadcasting & Cable interview that "If reporting on what's happening to ordinary people thrown overboard by circumstances beyond their control and betrayed by Washington officials is liberalism, I stand convicted."

Sinclair Broadcast Group, which owns broadcast stations affiliated with the major television networks, has been known for requiring its stations to run reports and editorials that promote conservative viewpoints. Its rapid growth through station group acquisitions—especially during the lead-up to the 2016 presidential elections—had provided an increasingly large platform for its views.

Several authors have written books on conservative bias in the media, including:

Reviewer John Moe sums up Alterman's views: "The conservatives in the newspapers, television, talk radio, and the Republican party are lying about liberal bias and repeating the same lies long enough that they've taken on a patina of truth. Further, the perception of such a bias has cowed many media outlets into presenting more conservative opinions to counterbalance a bias, which does not, in fact, exist."

Liberal Bias:

See also: Liberal bias in academia

Some critics of the media say liberal (or left wing) bias exists within a wide variety of media channels, especially within the mainstream media, including network news shows of CBS, ABC, and NBC, cable channels CNN, MSNBC and the former Current TV, as well as major newspapers, news-wires, and radio outlets, especially CBS News, Newsweek, and The New York Times.

These arguments intensified when it was revealed that the Democratic Party received a total donation of $1,020,816, given by 1,160 employees of the three major broadcast television networks (NBC, CBS, ABC), while the Republican Party received only $142,863 via 193 donations from employees of these same organizations. Both of these figures represent donations made in 2008.

A study cited frequently by those who make claims of liberal media bias in American journalism is The Media Elite, a 1986 book co-authored by political scientists Robert Lichter, Stanley Rothman, and Linda Lichter. They surveyed journalists at national media outlets such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the broadcast networks.

The survey found that the large majority of journalists were Democratic voters whose attitudes were well to the left of the general public on a variety of topics, including issues such as abortion, affirmative action, social services, and gay rights.

The authors compared journalists' attitudes to their coverage of issues such as the safety of nuclear power, school busing to promote racial integration, and the energy crisis of the 1970s and concluded firstly that journalists' coverage of controversial issues reflected their own attitudes and education, and secondly that the predominance of political liberals in newsrooms pushed news coverage in a liberal direction.

The authors suggested this tilt as a mostly unconscious process of like-minded individuals projecting their shared assumptions onto their interpretations of reality, a variation of confirmation bias.

Jim A. Kuypers of Dartmouth College investigated the issue of media bias in the 2002 book Press Bias and Politics. In this study of 116 mainstream U.S. papers, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle, Kuypers stated that the mainstream press in America tends to favor liberal viewpoints.

They argued that reporters who they thought were expressing moderate or conservative points of view were often labeled as holding a minority point of view. Kuypers said he found liberal bias in the reporting of a variety of issues including race, welfare reform, environmental protection, and gun control.

According to the Media Research Center, and David Brady of the Hoover Institute, conservative individuals and groups are more often labeled as such, than liberal individuals and groups.

A 2005 study by political scientists Tim Groseclose of UCLA and Jeff Milyo of the University of Missouri at Columbia attempted to quantify bias among news outlets using statistical models, and found a liberal bias. The authors wrote that "all of the news outlets we examine[d], except Fox News's Special Report and the Washington Times, received scores to the left of the average member of Congress." The study concluded that news pages of The Wall Street Journal were more liberal than The New York Times, and the news reporting of PBS was to the right of most mainstream media.

The report also stated that the news media showed a fair degree of centrism, since all but one of the outlets studied were, from an ideological point of view, between the average Democrat and average Republican in Congress. In a blog post, Mark Liberman, professor of computer science and the director of Linguistic Data Consortium at the University of Pennsylvania, critiqued the statistical model used in this study.

The model used by Groseclose and Milyo assumed that conservative politicians do not care about the ideological position of think tanks they cite, while liberal politicians do. Liberman characterized the unsupported assumption as preposterous and argued that it led to implausible conclusions.

A 2014 Gallup poll found that a plurality of Americans believe the media is biased to favor liberal politics. According to the poll, 44% of Americans feel that news media are "too liberal" (70% of self-identified conservatives, 35% of self-identified moderates, and 15% of self-identified liberals), while 19% believe them to be "too conservative" (12% of self-identified conservatives, 18% of self-identified moderates, and 33% of self-identified liberals), and 34% "just about right" (49% of self-identified liberals, 44% of self-identified moderates, and 16% of self-identified conservatives).

A 2008 joint study by the Joan Shorenstein Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University and the Project for Excellence in Journalism found that viewers believe a liberal media bias can be found in television news on networks such as CNN.

These findings concerning a perception of liberal bias in television news—particularly at CNN—were also reported by other sources. The study was met with criticism from media outlets and academics, including the Wall Street Journal, and progressive media watchdog Media Matters. Criticism from Media Matters included:

Authors:

Several authors have written books on liberal bias in the media, including

Racial Bias:

See also: Representation of African Americans in media

Political activist and one-time presidential candidate Rev. Jesse Jackson said in 1985 that the news media portray black people as "less intelligent than we are."

The IQ Controversy, the Media and Public Policy, a book published by Stanley Rothman and Mark Snyderman, claimed to document bias in media coverage of scientific findings regarding race and intelligence. Snyderman and Rothman stated that media reports often either erroneously reported that most experts believe that the genetic contribution to IQ is absolute or that most experts believe that genetics plays no role at all.

According to Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow, in 1986, many stories of the crack crisis broke out in the media. In these stories, African Americans were featured as "crack whores." The deaths of NBA player Len Bias and NFL player Don Rogers due to cocaine overdose only added to the media frenzy. Alexander claims in her book: "Between October 1988 and October 1989, the Washington Post alone ran 1,565 stories about the 'drug scourge.'"

One example of this double standard is the comparison of the deaths of Michael Brown and Dillon Taylor. On August 9, 2014, news broke out that Brown, a young, unarmed African American man, was shot and killed by a white policeman. This story spread throughout news media, explaining that the incident had to do with race. Only two days later, Taylor, another young, unarmed man, was shot and killed by a policeman. This story, however, did not get as highly publicized as Brown's. However unlike Brown's case, Taylor was white and Hispanic, while the police officer is black.

Research has shown that African Americans are over-represented in news reports on crime and that within those stories they are more likely to be shown as the perpetrators of the crime than as the persons reacting to or suffering from it. This perception that African Americans are over-represented in crime reporting persists even though crime statistics indicate that the percentage of African Americans who are convicted of crimes, and the percentage of African Americans who are victims of crimes, are both larger than the percentages for other racial and ethnic groups.

One of the most striking examples of racial bias was the portrayal of African Americans in the 1992 riots in Los Angeles. The media presented the riots as being an African American problem, deeming African Americans solely responsible for the riots. However, according to reports, only 36% of those arrested during the riots were African American. Some 60% of the rioters and looters were Hispanics and whites, facts that were not reported by the media.

Conversely, multiple commentators and newspaper articles have cited examples of the national media under-reporting interracial hate crimes when they involve white victims as compared to when they involve African Americans victims.

Jon Ham, a vice president of the conservative John Locke Foundation, wrote that "local officials and editors often claim that mentioning the black-on-white nature of the event might inflame passion, but they never have those same qualms when it's white-on-black."

According to David Niven, of Ohio State University, research shows that American media show bias on only two issues: race and gender equality.

Coverage of Electoral Politics:

Main article: Political handicapping

In the 19th century, many American newspapers made no pretense to lack of bias, openly advocating one or another political party. Big cities would often have competing newspapers supporting various political parties. To some extent this was mitigated by a separation between news and editorial. News reporting was expected to be relatively neutral or at least factual, whereas editorial was openly the opinion of the publisher. Editorials might also be accompanied by an editorial cartoon, which would frequently lampoon the publisher's opponents.

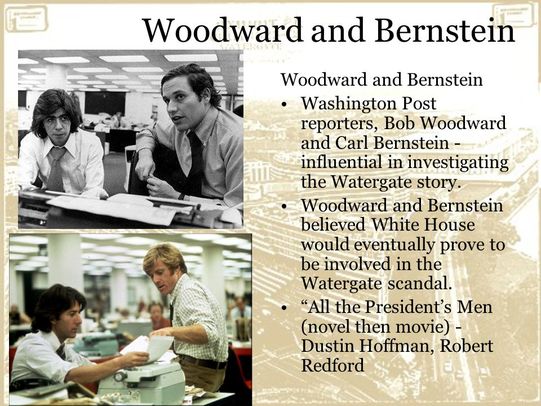

In an editorial for The American Conservative, Pat Buchanan wrote that reporting by "the liberal media establishment" on the Watergate scandal "played a central role in bringing down a president." Richard Nixon later complained, "I gave them a sword and they ran it right through me."

Nixon's Vice-President Spiro Agnew attacked the media in a series of speeches—two of the most famous having been written by White House aides William Safire and Buchanan himself—as "elitist" and "liberal." However, the media had also strongly criticized his Democratic predecessor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, for his handling of the Vietnam War, which culminated in him not seeking a second term.

In 2004, Steve Ansolabehere, Rebecca Lessem and Jim Snyder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzed the political orientation of endorsements by U.S. newspapers. They found an upward trend in the average propensity to endorse a candidate, and in particular an incumbent one.

There were also some changes in the average ideological slant of endorsements: while in the 1940s and in the 1950s there was a clear advantage to Republican candidates, this advantage continuously eroded in subsequent decades, to the extent that in the 1990s the authors found a slight Democratic lead in the average endorsement choice.

Riccardo Puglisi of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looks at the editorial choices of the New York Times from 1946 to 1997. He finds that the Times displays Democratic partisanship, with some watchdog aspects. This is the case, because during presidential campaigns the Times systematically gives more coverage to Democratic topics of civil rights, health care, labor and social welfare, but only when the incumbent president is a Republican.

These topics are classified as Democratic ones, because Gallup polls show that on average U.S. citizens think that Democratic candidates would be better at handling problems related to them. According to Puglisi, in the post-1960 period the Timesdisplays a more symmetric type of watchdog behavior, just because during presidential campaigns it also gives more coverage to the typically Republican issue of Defense when the incumbent President is a Democrat, and less so when the incumbent is a Republican.

John Lott and Kevin Hassett of the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute studied the coverage of economic news by looking at a panel of 389 U.S. newspapers from 1991 to 2004, and at a sub-sample of the two ten newspapers and the Associated Press from 1985 to 2004. For each release of official data about a set of economic indicators, the authors analyze how newspapers decide to report on them, as reflected by the tone of the related headlines.

The idea is to check whether newspapers display partisan bias, by giving more positive or negative coverage to the same economic figure, as a function of the political affiliation of the incumbent President. Controlling for the economic data being released, the authors find that there are between 9.6 and 14.7% fewer positive stories when the incumbent President is a Republican.

According to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, a liberal watchdog group, Democratic candidate John Edwards was falsely maligned and was not given coverage commensurate with his standing in presidential campaign coverage because his message questioned corporate power.

A 2000 meta-analysis of research in 59 quantitative studies of media bias in American presidential campaigns from 1948 through 1996 found that media bias tends to cancel out, leaving little or no net bias. The authors conclude "It is clear that the major source of bias charges is the individual perceptions of media consumers and, in particular, media consumers of a particularly ideological bent."

It has also been acknowledged that media outlets have often used horse-race journalism with the intent of making elections more competitive. This form of political coverage involves diverting attention away from stronger candidates and hyping so-called dark horse contenders who seem more unlikely to win when the election cycle begins.

Benjamin Disraeli used the term " dark horse" to describe horse racing in 1831 in The Young Duke, writing, "a dark horse which had never been thought of and which the careless St. James had never even observed in the list, rushed past the grandstand in sweeping triumph."

Political analyst Larry Sabato stated in his 2006 book Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections that Disraeli's description of dark horses "now fits in neatly with the media's trend towards horse-race journalism and penchant for using sports analogies to describe presidential politics."

Often in contrast with national media, political science scholars seek to compile long-term data and research on the impact of political issues and voting in U.S. presidential elections, producing in-depth articles breaking down the issues.

2000 Presidential Election:

During the course of the 2000 presidential election, some pundits accused the mainstream media of distorting facts in an effort to help Texas Governor George W. Bush win the 2000 Presidential Election after Bush and Al Gore officially launched their campaigns in 1999.

Peter Hart and Jim Naureckas, two commentators for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), called the media "serial exaggerators" and argued that several media outlets were constantly exaggerating criticism of Gore, like falsely claiming that Gore lied when he claimed he spoke in an overcrowded science class in Sarasota, Florida, and giving Bush a pass on certain issues, such as the fact that Bush wildly exaggerated how much money he signed into the annual Texas state budget to help the uninsured during his second debate with Gore in October 2000.

In the April 2000 issue of Washington Monthly, columnist Robert Parry also argued that several media outlets exaggerated Gore's supposed claim that he "discovered" the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York during a campaign speech in Concord, New Hampshire on November 30, 1999, when he had only claimed he "found" it after it was already evacuated in 1978 because of chemical contamination.

Rolling Stone columnist Eric Boehlert also argued that media outlets exaggerated criticism of Gore as early as July 22, 1999, when Gore, known for being an environmentalist, had a friend release 500 million gallons of water into a drought stricken river to help keep his boat afloat for a photo shot; media outlets, however, exaggerated the actual number of gallons that were released and claimed it was 4 billion.

2008 Presidential election:

In the 2008 presidential election, media outlets were accused of discrediting Barack Obama's opponents in an effort to help him win the Democratic nomination and later the Presidential election. At the February debate, Tim Russert of NBC News was criticized for what some perceived as disproportionately tough questioning of Democratic presidential contender Hillary Clinton.

Among the questions, Russert had asked Clinton, but not Obama, to provide the name of the new Russian President (Dmitry Medvedev). This was later parodied on Saturday Night Live. In October 2007, liberal commentators accused Russert of harassing Clinton over the issue of supporting drivers' licenses for illegal immigrants.

On April 16, 2008 ABC News hosted a debate in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Moderators Charles Gibson and George Stephanopoulos were criticized by viewers, bloggers and media critics for the poor quality of their questions. Many viewers said they considered some of the questions irrelevant when measured against the importance of the faltering economy or the Iraq war.

Included in that category were continued questions about Obama's former pastor, Clinton's assertion that she had to duck sniper fire in Bosnia more than a decade ago, and Obama's not wearing an American flag pin. The moderators focused on campaign gaffes and some believed they focused too much on Obama. Stephanopoulos defended their performance, saying "Senator Obama was the front-runner" and the questions were "not inappropriate or irrelevant at all."

In an op-ed published on April 27, 2008, in The New York Times, Elizabeth Edwards wrote that the media covered much more of "the rancor of the campaign" and "amount of money spent" than "the candidates' priorities, policies and principles."

Author Erica Jong commented that "our press has become a sea of triviality, meanness and irrelevant chatter." A Gallup poll released on May 29, 2008 also estimated that more Americans felt the media was being harder on Clinton than they were on Obama.

In a joint study by the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University and the Project for Excellence in Journalism, the authors found disparate treatment by the three major cable networks of Republican and Democratic candidates during the earliest five months of presidential primaries in 2007: "The CNN programming studied tended to cast a negative light on Republican candidates—by a margin of three-to-one.

Four-in-ten stories (41%) were clearly negative while just 14% were positive and 46% were neutral. The network provided negative coverage of all three main candidates with McCain faring the worst (63% negative) and Romney faring a little better than the others only because a majority of his coverage was neutral. It's not that Democrats, other than Obama, fared well on CNN either.

Nearly half of the Illinois Senator's stories were positive (46%), vs. just 8% that were negative. But both Clinton and Edwards ended up with more negative than positive coverage overall. So while coverage for Democrats overall was a bit more positive than negative, that was almost all due to extremely favorable coverage for Obama."

A poll of likely 2008 United States presidential election voters released on March 14, 2007 by Zogby International reports that 83 percent of those surveyed believe that there is a bias in the media, with 64 percent of respondents of the opinion that this bias favors liberals and 28 percent of respondents believing that this bias is conservative.

In August 2008 the Washington Post ombudsman wrote that the Post had published almost three times as many page 1 stories about Obama than it had about John McCain since Obama won the Democratic party nomination that June. In September 2008 a Rasmussen poll found that 68 percent of voters believed that "most reporters try to help the candidate they want to win."

Forty-nine (49) percent of respondents stated that the reporters were helping Obama to get elected, while only 14 percent said the same regarding McCain. A further 51 percent said that the press was actively "trying to hurt" Republican Vice Presidential nominee Sarah Palin with negative coverage.

In October 2008, Washington Post media correspondent Howard Kurtz reported that Palin was again on the cover of Newsweek, "but with the most biased campaign headline I've ever seen."

After the election was over, Washington Post ombudsman Deborah Howell reviewed the Post's coverage and concluded that it was slanted in favor of Obama. "The Post provided a lot of good campaign coverage, but readers have been consistently critical of the lack of probing issues coverage and what they saw as a tilt toward Democrat Barack Obama. My surveys, which ended on Election Day, show that they are right on both counts."

Over the course of the campaign, the Post printed 594 "issues stories" and 1,295 "horse-race stories." There were more positive opinion pieces on Obama than McCain (32 to 13) and more negative pieces about McCain than Obama (58 to 32). Overall, more news stories were dedicated to Obama than McCain. Howell said that the results of her survey were comparable to those reported by the Project for Excellence in Journalism for the national media. (That report, issued on October 22, 2008, found that "coverage of McCain has been heavily unfavorable," with 57% of the stories issued after the conventions being negative and only 14% being positive.

For the same period, 36% of the stories on Obama were positive, 35% were neutral or mixed, and 29% were negative. While rating the Post's biographical stories as generally quite good, she concluded that "Obama deserved tougher scrutiny than he got, especially of his undergraduate years, his start in Chicago and his relationship with Antoin 'Tony' Rezko, who was convicted this year of influence-peddling in Chicago. The Post did nothing on Obama's acknowledged drug use as a teenager."

Various critics, particularly Hudson, have shown concern over the link between the news media's reporting and what they see as the trivialized nature of American elections.

Hudson argued that America's news media elections coverage damages the democratic process. He argues that elections are centered on candidates, whose advancement depends on funds, personality and sound-bites, rather than serious political discussion or policies offered by parties. His argument is that it is on the media which Americans are dependent for information about politics (this is of course true almost by definition) and that they are therefore greatly influenced by the way the media report, which concentrates on short sound-bites, gaffes by candidates, and scandals.

The reporting of elections avoids complex issues or issues which are time-consuming to explain. Of course, important political issues are generally both complex and time-consuming to explain, so are avoided.

Hudson blames this style of media coverage, at least partly, for trivialized elections:

"The bites of information voters receive from both print and electronic media are simply insufficient for constructive political discourse. ... candidates for office have adjusted their style of campaigning in response to this tabloid style of media coverage. ... modern campaigns are exercises in image manipulation. ... Elections decided on sound bites, negative campaign commercials, and sensationalized exposure of personal character flaws provide no meaningful direction for government".

2016 Presidental Election:

Beginning in the middle of May 2016, Donald Trump attacked CNN and other media outlets that he believes is spreading "fake news" and "is totally against him"

Post Election Coverage:

As of December 2017, President Trump has continued to call media outlets "fake news".

Coverage of Foreign Issues:

In addition to philosophical or economic biases, there are also subject biases, including criticism of media coverage about foreign policy issues as being overly centered in Washington, D.C.. Coverage is variously cited as being: 'Beltway centrism', framed in terms of domestic politics and established policy positions, only following Washington's 'Official Agendas', and mirroring only a 'Washington Consensus'.

Regardless of the criticism, according to the Columbia Journalism Review, "No news subject generates more complaints about media objectivity than the Middle East in general and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in particular."

Coverage of the Vietnam War:

Main article: U.S. news media and the Vietnam War

Coverage of the Arab–Israeli conflict:

Main article: Media coverage of the Arab–Israeli conflict

Pro-Israel media:

Stephen Zunes wrote that "mainstream and conservative Jewish organizations have mobilized considerable lobbying resources, financial contributions from the Jewish community, and citizen pressure on the news media and other forums of public discourse in support of the Israeli government."

According to CUNY professor of journalism Eric Alterman, debate among Middle East pundits, "is dominated by people who cannot imagine criticizing Israel". In 2002, he listed 56 columnists and commentators who can be counted on to support Israel "reflexively and without qualification." Alterman only identified five pundits who consistently criticize Israeli behavior or endorse pro-Arab positions.

Journalists described as pro-Israel by Mearsheimer and Walt include: the New York Times' William Safire, A.M. Rosenthal, David Brooks, and Thomas Friedman (although they say that the latter is sometimes critical of areas of Israel policy); the Washington Post's Jim Hoagland, Robert Kagan, Charles Krauthammer and George Will; and the Los Angeles Times' Max Boot, Jonah Goldberg and Jonathan Chait.

The 2007 book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy argued that there is a media bias in favor of Israel. It stated that a former spokesman for the Israeli Consulate in New York said that: "Of course, a lot of self-censorship goes on. Journalists, editors, and politicians are going to think twice about criticizing Israel if they know they are going to get thousands of angry calls in a matter of hours. The Jewish lobby is good at orchestrating pressure."

Journalist Michael Massing wrote in 2006 that "Jewish organizations are quick to detect bias in the coverage of the Middle East, and quick to complain about it. That's especially true of late. As The Forward observed in late April [2002], 'rooting out perceived anti-Israel bias in the media has become for many American Jews the most direct and emotional outlet for connecting with the conflict 6,000 miles away.'"

The Forward related how one individual felt: "'There's a great frustration that American Jews want to do something,' said Ira Youdovin, executive vice president of the Chicago Board of Rabbis. 'In 1947, some number would have enlisted in the Haganah,' he said, referring to the pre-state Jewish armed force. 'There was a special American brigade. Nowadays you can't do that. The battle here is the hasbarah war,' Youdovin said, using a Hebrew term for public relations. 'We're winning, but we're very much concerned about the bad stuff.'"

A 2003 Boston Globe article on the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America media watchdog group by Mark Jurkowitz argued that: "To its supporters, CAMERA is figuratively – and perhaps literally – doing God's work, battling insidious anti-Israeli bias in the media. But its detractors see CAMERA as a myopic and vindictive special interest group trying to muscle its views into media coverage."

Pro-Palestine media:

Several sources indicate that increased support of Palestine and increased bias against Israel by international media are correlated to spikes in anti-semitic acts. According to Gary Weiss, due to intimidation of international journalists by Palestine and bias in American mainstream media, American media have "become part of the Hamas war machine".

Coverage of the Iraq War:

Main article: Media coverage of the Iraq War

Suggestions of insufficiently critical media coverage. In 2003, a study released by Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting stated the network news disproportionately focused on pro-war sources and left out many anti-war sources. According to the study, 64% of total sources were in favor of the Iraq War while total anti-war sources made up 10% of the media (only 3% of US sources were anti-war). The study stated that "viewers were more than six times as likely to see a pro-war source as one who was anti-war; with U.S. guests alone, the ratio increases to 25 to 1."

In February 2004, a study was released by the liberal national media watchdog group FAIR. According to the study, which took place during October 2003, current or former government or military officials accounted for 76 percent of all 319 sources for news stories about Iraq which aired on network news channels.

On March 23, 2006, the US designated the Hezbollah affiliated media, Al-Nour Radio and Al-Manar TV station, as "terrorist entities" through legislative language as well as support of a letter to President Bush signed by 51 senators.

Suggestions of overly critical media coverage:

Some critics believe that, on the contrary, the American media have been too critical of U.S. forces. Rick Mullen, a former journalist, Vietnam veteran, and U.S. Marine Corps reserve officer, has suggested that American media coverage has been unfair, and has failed to send a message adequately supportive of U.S. forces.

Mullen calls for a lesser reporting of transgressions by US forces (condemning "American media pouncing on every transgression"), and a more extensive reporting of US forces' positive actions, which Mullen feels are inadequately reported (condemning the media for "ignoring the legions of good and noble deeds by US and coalition forces"). Mullen compares critical media reports to the 9/11 terrorist attacks:

"I have got used to our American media pouncing on every transgression by U.S. Forces while ignoring the legions of good and noble deeds performed by U.S. and coalition forces in both Iraq and Afghanistan... This sort of thing is akin to the evening news focusing on the few bad things that happen in Los Angeles or London and ignoring the millions of good news items each day... I am sure that you are aware that it is not the enemy's objective to defeat us on the battlefield but to defeat our national will to prevail.

That battle is fought in the living rooms of America and England and the medium used is the TV news and newspapers. The enemy is not stupid. As on 9/11, they plan to use our "systems" against us, the news media being the most important "system" in their pursuit to break our national will." —Rick Mullen, Letter to The London Times, 2006.

News sources:

A widely cited public opinion study documented a correlation between news source and certain misconceptions about the Iraq war. Conducted by the Program on International Policy Attitudes in October 2003, the poll asked Americans whether they believed statements about the Iraq war that were known to be false. Respondents were also asked for their primary news source: Fox News, CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN, "Print sources," or NPR.

By cross referencing the respondents to their primary news source, the study showed that more Fox News watchers held those misconceptions about the Iraq war. Director of Program on International Policy (PIPA) Stephen Kull said, "While we cannot assert that these misconceptions created the support for going to war with Iraq, it does appear likely that support for the war would be substantially lower if fewer members of the public had these misperceptions."

Bias in entertainment media:

Primetime Propaganda: The True Hollywood Story of How the Left Took Over Your TV, a 2011 book by Ben Shapiro, argues that producers, executives and writers in the entertainment industry are using television to promote a liberal political agenda.

The claims include both blatant and subtle liberal agendas in entertainment shows, discrimination against conservatives in the industry, and misleading advertisers regarding the value of liberal leaning market segments. As one part of the evidence, he presents statements from taped interviews made by celebrities and T.V. show creators from Hollywood whom he interviewed for the book.

Some comic strips have been accused of bias. The Doonesbury comic strip has a liberal point of view. In 2004 a conservative letter writing campaign was successful in convincing Continental Features, a company that prints many Sunday comics sections, to refuse to print the strip, causing Doonesbury to disappear from the Sunday comics in 38 newspapers.

Of the 38, only one editor, Troy Turner, executive editor of the Anniston Star in Alabama, continued to run the Sunday Doonesbury, albeit necessarily in black and white. Mallard Fillmore by Bruce Tinsley and Prickly City by Scott Stantis are both conservative in their views.

In older strips, Li'l Abner by Al Capp routinely parodied Southern Democrats through the character of Senator Jack S. Phogbound, but later adopted a strongly conservative stance.

Pogo by Walt Kelly caricatured a wide range of political figures including Joseph McCarthy, Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, George Wallace, Robert F. Kennedy, and Eugene McCarthy.

Little Orphan Annie espoused a strong anti-union pro-business stance in the story "Eonite" from 1935, where union agitators destroy a business that would have benefited the entire human race.

Causes of the Perception of Bias:

Jonathan M. Ladd, who has conducted intensive studies of media trust and media bias, concluded that the primary cause of belief in media bias is media telling their audience that particular media are biased.

People who are told that a medium is biased tend to believe that it is biased, and this belief is unrelated to whether that medium is actually biased or not. The only other factor with as strong an influence on belief that media is biased is extensive coverage of celebrities. A majority of people see such media as biased, while at the same time preferring media with extensive coverage of celebrities.

Watchdog Groups:

Reporters Without Borders has said that the media in the United States lost a great deal of freedom between the 2004 and 2006 indices, citing the Judith Miller case and similar cases and laws restricting the confidentiality of sources as the main factors. They also cite the fact that reporters who question the American "war on terror" are sometimes regarded as suspicious.

They rank the U.S. as 53rd out of 168 countries in freedom of the press, comparable to Japan and Uruguay, but below all but one European Union country (Poland) and below most OECD countries (countries that accept democracy and free markets). In the 2008 ranking, the U.S. moved up to 36, between Taiwan and Macedonia, but still far below its ranking in the late 20th century as a world leader in having a free and unbiased press.

Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), is a self-described progressive media watch group.

Media Matters for America, another self-described progressive media watch group, dedicates itself to "monitoring, analyzing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media."

Conservative organizations Accuracy In Media and Media Research Center argue that the media has a liberal bias, and are dedicated to publicizing that opinion. The Media Research Center, for example, was founded with the specific intention to "prove ... that liberal bias in the media does exist and undermines traditional American values".

Groups such as FactCheck argue that the media frequently gets the facts wrong because they rely on biased sources of information. This includes using information provided to them from both parties.

After the Press is a news blog that follows the press to stories of national interest across America and shows the side of the story that mainstream media does not air.[

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Media Bias in the United States:

Claims of media bias in the United States include claims of liberal bias, conservative bias, mainstream bias, and corporate bias. To combat this, a variety of watchdog groups attempt to find the facts behind both biased reporting and unfounded claims of bias. Research about media bias is now a subject of systematic scholarship in a variety of disciplines.

Demographic polling:

A 1956 American National Election Study found that 66% of Americans thought newspapers were fair, including 78% of Republicans and 64% of Democrats.

A 1964 poll by the Roper Organization asked a similar question about network news, and 71% thought network news was fair.

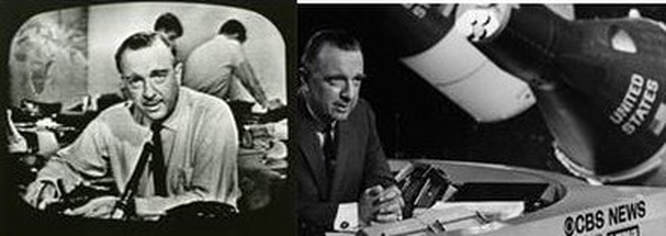

A 1972 poll found that 72% of Americans trusted CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite.

According to Jonathan M. Ladd's Why Americans Hate the Media and How it Matters, "Once, institutional journalists were powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse."

That has changed. Gallup Polls since 1997 have shown that most Americans do not have confidence in the mass media "to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly". According to Gallup, the American public's trust in the media has generally declined in the first decade and a half of the 21st century.

Again according to Ladd, "In the 2008, the portion of Americans expressing 'hardly any' confidence in the press had risen to 45%. A 2004 Chronicle of Higher Education poll found that only 10% of Americans had 'a great deal' of confidence in the 'national news media,'"

In 2011, only 44% of those surveyed had "a great deal" or "a fair amount" of trust and confidence in the mass media. In 2013, a 59% majority reported a perception of media bias, with 46% saying mass media was too liberal and 13% saying it was too conservative.

The perception of bias was highest among conservatives. According to the poll, 78% of conservatives think the mass media is biased, as compared with 44% of liberals and 50% of moderates. Only about 36% view mass media reporting as "just about right".

News Values:

Main article: News values

According to Jonathan M. Ladd, Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters, "The existence of an independent, powerful, widely respected news media establishment is an historical anomaly. Prior to the twentieth century, such an institution had never existed in American history." However, he looks back to the period between 1950 and 1979 as a period where "institutional journalists were powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse."

A number of writers have tried to explain the decline in journalistic standards. One explanation is the 24-hour news cycle, which faces the necessity of generating news even when no news-worthy events occur. Another is the simple fact that bad news sells more newspapers than good news. A third possible factor is the market for "news" that reinforces the prejudices of a target audience.

"In a 2010 paper, Mr. Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, a frequent collaborator and fellow professor at Chicago Booth, found that ideological slants in newspaper coverage typically resulted from what the audience wanted to read in the media they sought out, rather than from the newspaper owners' biases."

Framing:

An important aspect of media bias is framing. A frame is the arrangement of a news story, with the goal of influencing audience to favor one side or the other. The ways in which stories are framed can greatly undermine the standards of reporting such as fairness and balance. Many media outlets are known for their outright bias. Some outlets, such as MSNBC, are known for their liberal views, while others, such as Fox News Channel, are known for their conservative views. How biased media frame stories can change audience reactions.

Corporate bias and power bias:

See also:

Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media proposed a propaganda model to explain systematic biases of U.S. media as a consequence of the pressure to create a stable and profitable business. In this view, corporate interests create five filters that bias news in their favor.

Pro-power and pro-government bias:

Part of the propaganda model is self-censorship through the corporate system (see corporate censorship); that reporters and especially editors share or acquire values that agree with corporate elites in order to further their careers. Those who do not are marginalized or fired.

Such examples have been dramatized in fact-based movie dramas such as Good Night, and Good Luck and The Insider and demonstrated in the documentary The Corporation.

George Orwell originally wrote a preface for his 1945 novel Animal Farm, which focused on the British self-censorship of the time: "The sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary. ... [Things are] kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervened but because of a general tacit agreement that 'it wouldn't do' to mention that particular fact." The preface was not published with most copies of the book.

In the propaganda model, advertising revenue is essential for funding most media sources and thus linked with media coverage. For example, according to Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR.org), 'When Al Gore proposed launching a progressive TV network, a Fox News executive told Advertising Age (10/13/03): "The problem with being associated as liberal is that they wouldn't be going in a direction that advertisers are really interested in....

If you go out and say that you are a liberal network, you are cutting your potential audience, and certainly your potential advertising pool, right off the bat." An internal memo from ABC Radio affiliates in 2006 revealed that powerful sponsors had a "standing order that their commercials never be placed on syndicated Air America programming" that aired on ABC affiliates.

The list totaled 90 advertisers and included major corporations such as Wal-Mart, GE, Exxon Mobil, Microsoft, Bank of America, FedEx, Visa, Allstate, McDonald's, Sony and Johnson & Johnson, and government entities such as the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. Navy.

According to Chomsky, U.S. commercial media encourage controversy only within a narrow range of opinion, in order to give the impression of open debate, and do not report on news that falls outside that range.

Herman and Chomsky argue that comparing the journalistic media product to the voting record of journalists is as flawed a logic as implying auto-factory workers design the cars they help produce. They concede that media owners and news makers have an agenda, but that this agenda is subordinated to corporate interests leaning to the right.

It has been argued by some critics, including historian Howard Zinn and Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges, that the corporate media routinely ignore the plight of the impoverished while painting a picture of a prosperous America.

In 2008 George W. Bush's press secretary Scott McClellan published a book in which he confessed to regularly and routinely, but unknowingly, passing on lies to the media, following the instructions of his superiors, lies that the media reported as facts. He characterized the press as, by and large, honest, and intent on telling the truth, but reported that "the national press corps was probably too deferential to the White House", especially on the subject of the war in Iraq.

FAIR reported that between January and August 2014 no representatives for organized labor made an appearance on any of the high-profile Sunday morning talkshows (NBC's Meet the Press, ABC's This Week, Fox News Sunday and CBS's Face the Nation), including episodes that covered topics such as labor rights and jobs, while current or former corporate CEOs made 12 appearances over that same period.

Corporate Control:

Six following six corporate conglomerates own the majority of mass media outlets in the United States:

Such a uniformity of ownership means that stories which are critical of these corporations may often be underplayed in the media. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 enabled this handful of corporations to expand their power, and according to Howard Zinn, such mergers "enabled tighter control of information."

Chris Hedges argues that corporate media control "of nearly everything we read, watch or hear" is an aspect of what political philosopher Sheldon Wolin calls inverted totalitarianism.

In the United States most media are operated for profit, and are usually funded by advertising. Stories critical of advertisers or their interests may be underplayed, while stories favorable to advertisers may be given more coverage.

"InfoTainment":

Main article: Infotainment

Academics such as McKay, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, and Hudson (see below) have described private U.S. media outlets as profit-driven. For the private media, profits are dependent on viewing figures, regardless of whether the viewers found the programs adequate or outstanding. The strong profit-making incentive of the American media leads them to seek a simplified format and uncontroversial position which will be adequate for the largest possible audience.

The market mechanism only rewards media outlets based on the number of viewers who watch those outlets, not by how informed the viewers are, how good the analysis is, or how impressed the viewers are by that analysis.

According to some, the profit-driven quest for high numbers of viewers, rather than high quality for viewers, has resulted in a slide from serious news and analysis to entertainment, sometimes called infotainment:

"Imitating the rhythm of sports reports, exciting live coverage of major political crises and foreign wars was now available for viewers in the safety of their own homes. By the late-1980s, this combination of information and entertainment in news programmes was known as infotainment." [Barbrook, Media Freedom, (London, Pluto Press, 1995) part 14]

Oversimplification:

Kathleen Hall Jamieson claimed in her book The Interplay of Influence: News, Advertising, Politics, and the Internet that most television news stories are made to fit into one of five categories:

- Appearance versus reality

- Little guys versus big guys

- Good versus evil