Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Law and Order in the United States

covers the legal system and law enforcement in general, including the Justice System (whether criminal or civil), at the federal, state, county and city level, and including international law enforcement as it impacts the United States

See Also:

Cybersecurity

Law including its Enforcement in the United States (at both the Federal and State/Local Level)

YouTube Video: Risk Takers in the Coast Guard

(United States Coast Guard: Whether patrolling or flying search and rescue missions, the United States coast guard is always ready to put to serve and protect. The coast guardsmen stationed in Florida battle dangerous conditions every day to enforce the law, and save lives.)

YouTube Video: A History of the United States Supreme Court. This video covers the history of the Supreme Court from the its earliest ruling until the end of the 20th century. The court has changed over time and this video tells that story.

Pictured: LEFT: Logo of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); RIGHT: the Scale of Justice

Law is a system of rules that are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior.

Laws can be made by a collective legislature or by a single legislator, resulting in statutes, by the executive through decrees and regulations, or by judges through binding precedent, normally in common law jurisdictions.

Private individuals can create legally binding contracts, including arbitration agreements that may elect to accept alternative arbitration to the normal court process.

The formation of laws themselves may be influenced by a constitution, written or tacit, and the rights encoded therein. The law shapes politics, economics, history and society in various ways and serves as a mediator of relations between people.

A general distinction can be made between (a) civil law jurisdictions, in which the legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates their laws, and (b) common law systems, where judicial-made precedent is accepted as binding law.

The adjudication of the law is generally divided into two main areas referred to as (i) Criminal law and (ii) Civil law. Criminal law deals with conduct that is considered harmful to social order and in which the guilty party may be imprisoned or fined. Civil law (not to be confused with civil law jurisdictions above) deals with the resolution of lawsuits (disputes) between individuals or organizations.

Law provides a rich source of scholarly inquiry into legal history, philosophy, economic analysis and sociology. Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice.

Law enforcement in the United States is one of three major components of criminal justice system of the United States, along with courts and corrections. Although each component operates semi-independently, the three collectively form a chain leading from investigation of suspected criminal activity to administration of criminal punishment.

Also, courts are vested with the power to make legal determinations regarding the conduct of the other two components.Law enforcement operates primarily through governmental police agencies. The law-enforcement purposes of these agencies are the investigation of suspected criminal activity, referral of the results of investigations to the courts, and the temporary detention of suspected criminals pending judicial action.

Law enforcement agencies, to varying degrees at different levels of government and in different agencies, are also commonly charged with the responsibilities of deterring criminal activity and preventing the successful commission of crimes in progress.

Other law enforcement duties may include the service and enforcement of warrants, writs, and other orders of the courts.

Law enforcement agencies are also involved in providing first response to emergencies and other threats to public safety; the protection of certain public facilities and infrastructure; the maintenance of public order; the protection of public officials; and the operation of some correctional facilities (usually at the local level).

Federal Law Enforcement in the United States:

The federal government of the United States empowers a wide range of law enforcement agencies to maintain law and public order related to matters affecting the country as a whole.

Click on any of the following links for amplification on Federal Law Enforcement

State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies:

Click Here for an Alphabetical listing of state and local law enforcement agencies in the United States

Laws can be made by a collective legislature or by a single legislator, resulting in statutes, by the executive through decrees and regulations, or by judges through binding precedent, normally in common law jurisdictions.

Private individuals can create legally binding contracts, including arbitration agreements that may elect to accept alternative arbitration to the normal court process.

The formation of laws themselves may be influenced by a constitution, written or tacit, and the rights encoded therein. The law shapes politics, economics, history and society in various ways and serves as a mediator of relations between people.

A general distinction can be made between (a) civil law jurisdictions, in which the legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates their laws, and (b) common law systems, where judicial-made precedent is accepted as binding law.

The adjudication of the law is generally divided into two main areas referred to as (i) Criminal law and (ii) Civil law. Criminal law deals with conduct that is considered harmful to social order and in which the guilty party may be imprisoned or fined. Civil law (not to be confused with civil law jurisdictions above) deals with the resolution of lawsuits (disputes) between individuals or organizations.

Law provides a rich source of scholarly inquiry into legal history, philosophy, economic analysis and sociology. Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice.

Law enforcement in the United States is one of three major components of criminal justice system of the United States, along with courts and corrections. Although each component operates semi-independently, the three collectively form a chain leading from investigation of suspected criminal activity to administration of criminal punishment.

Also, courts are vested with the power to make legal determinations regarding the conduct of the other two components.Law enforcement operates primarily through governmental police agencies. The law-enforcement purposes of these agencies are the investigation of suspected criminal activity, referral of the results of investigations to the courts, and the temporary detention of suspected criminals pending judicial action.

Law enforcement agencies, to varying degrees at different levels of government and in different agencies, are also commonly charged with the responsibilities of deterring criminal activity and preventing the successful commission of crimes in progress.

Other law enforcement duties may include the service and enforcement of warrants, writs, and other orders of the courts.

Law enforcement agencies are also involved in providing first response to emergencies and other threats to public safety; the protection of certain public facilities and infrastructure; the maintenance of public order; the protection of public officials; and the operation of some correctional facilities (usually at the local level).

Federal Law Enforcement in the United States:

The federal government of the United States empowers a wide range of law enforcement agencies to maintain law and public order related to matters affecting the country as a whole.

Click on any of the following links for amplification on Federal Law Enforcement

State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies:

Click Here for an Alphabetical listing of state and local law enforcement agencies in the United States

United States Department of Justice , including the Attorney General who heads up the Department of Justice

Pictured: Department of Justice: LEFT: Seal; RIGHT: Robert F. Kennedy Department of Justice Building

- YouTube Video of the Department of Justice*

- YouTube Video: An Inside Look at the Department of Justice

- YouTube Video: DOJ & Administration Officials Announced New Charges and Progress in Paycheck Protection Program

Pictured: Department of Justice: LEFT: Seal; RIGHT: Robert F. Kennedy Department of Justice Building

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the U.S. government, responsible for the enforcement of the law and administration of justice in the United States, equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries.

The Department is headed by the United States Attorney General (see below) who is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate and is a member of the Cabinet.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification: ___________________________________________________________________________

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) leads the United States Department of Justice (above) and is the chief lawyer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all legal matters. The attorney general is a statutory member of the Cabinet of the United States.

Under the Appointments Clause of the United States Constitution, the officeholder is nominated by the president of the United States, then appointed with the advice and consent of the United States Senate.

The attorney general is supported by the Office of the Attorney General, which includes executive staff and several deputies.

Merrick Garland has been the United States attorney general since March 11, 2021.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Attorney General:

The Department is headed by the United States Attorney General (see below) who is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate and is a member of the Cabinet.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification: ___________________________________________________________________________

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) leads the United States Department of Justice (above) and is the chief lawyer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all legal matters. The attorney general is a statutory member of the Cabinet of the United States.

Under the Appointments Clause of the United States Constitution, the officeholder is nominated by the president of the United States, then appointed with the advice and consent of the United States Senate.

The attorney general is supported by the Office of the Attorney General, which includes executive staff and several deputies.

Merrick Garland has been the United States attorney general since March 11, 2021.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Attorney General:

- History

- Presidential transition

- List of attorneys general

- Living former U.S. attorneys general

- Line of succession

- See also:

- Official website

- List of living former members of the United States Cabinet

- Executive Order 13787 for "Providing an Order of Succession Within the Department of Justice"

Forensic Science, including Ten Modern Forensic Science Technologies

YouTube Video about Forensic Science

YouTube Video Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS)

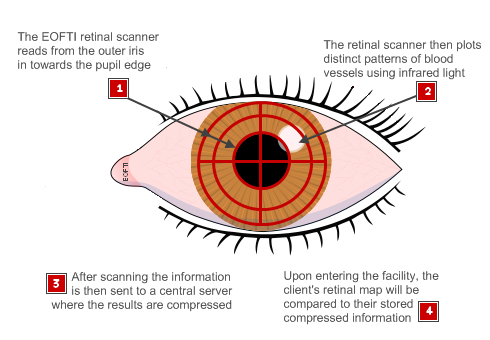

Pictured: Retinal (Eye) Scanning Illustrated

Forensic science is the application of science to criminal and civil laws. Forensic scientists collect, preserve, and analyze scientific evidence during the course of an investigation.

While some forensic scientists travel to the scene to collect the evidence themselves, others occupy a laboratory role, performing analysis on objects brought to them by other individuals.

In addition to their laboratory role, forensic scientists testify as expert witnesses in both criminal and civil cases and can work for either the prosecution or the defense. While any field could technically be forensic, certain sections have developed over time to encompass the majority of forensically related cases.

For amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

___________________________________________________________________________

10 Modern Forensic Science Technologies:

As technology infiltrates every aspect of our lives, it is no wonder that solving crimes has become almost futuristic in its advances. From retinal scanning to trace evidence chemistry, actual forensic technologies are so advanced at helping to solve crimes that they seem like something from a science fiction thriller.

With all this forensic technology, its no wonder that this field is one of the fastest growing in the U.S. Shows like CSI and NCIS have made most of the forensic science techniques used today common knowledge. You might think that virtually the whole gamut of forensic technology is old hat to today’s savvy viewer. In fact, there are a number of incredibly cool forensic technologies that you probably never knew existed.

10 COOL TECHNOLOGIES USED IN FORENSIC SCIENCE

METHODOLOGY FOR THE FEATURED FORENSIC SCIENCE TECHNOLOGIES

When deciding which technologies to include on this list, a number of factors were taken into consideration.

Sources:

Writer: Willow Dawn Becker: Willow is a blogger, parent, former educator and regular contributor to www.forensicscolleges.com. When she's not writing about forensic science, you'll find her blogging about education online, or enjoying the beauty of Oregon.

While some forensic scientists travel to the scene to collect the evidence themselves, others occupy a laboratory role, performing analysis on objects brought to them by other individuals.

In addition to their laboratory role, forensic scientists testify as expert witnesses in both criminal and civil cases and can work for either the prosecution or the defense. While any field could technically be forensic, certain sections have developed over time to encompass the majority of forensically related cases.

For amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

- History

- Subdivisions

- Questionable techniques

- Litigation science

- International demographics

- Examples in popular culture

- Controversies

- Forensic science and humanitarian work

- See also:

- American Academy of Forensic Sciences

- Association of Firearm and Tool Mark Examiners

- Ballistic fingerprinting

- Bloodstain pattern analysis

- Computer forensics

- Crime

- Computational forensics

- Diplomatics (Forensic paleography)

- Fingerprint

- Footprints

- Forensic accounting

- Forensic animation

- Forensic anthropology

- Forensic biology

- Forensic chemistry

- Forensic economics

- Forensic engineering

- Forensic entomology

- Forensic facial reconstruction

- Forensic identification

- Forensic linguistics

- Forensic materials engineering

- Forensic photography

- Forensic polymer engineering

- Forensic profiling

- Forensic psychiatry

- Forensic psychology

- Forensic seismology

- Forensic social work

- Forensic video analysis

- Glove prints

- Marine forensics

- Offender profiling

- Questioned document examination

- Retrospective diagnosis

- RSID

- Scenes of Crime Officer

- Skid mark

- Trace evidence

- Profiling (information science)

- Wildlife Forensic Science

___________________________________________________________________________

10 Modern Forensic Science Technologies:

As technology infiltrates every aspect of our lives, it is no wonder that solving crimes has become almost futuristic in its advances. From retinal scanning to trace evidence chemistry, actual forensic technologies are so advanced at helping to solve crimes that they seem like something from a science fiction thriller.

With all this forensic technology, its no wonder that this field is one of the fastest growing in the U.S. Shows like CSI and NCIS have made most of the forensic science techniques used today common knowledge. You might think that virtually the whole gamut of forensic technology is old hat to today’s savvy viewer. In fact, there are a number of incredibly cool forensic technologies that you probably never knew existed.

10 COOL TECHNOLOGIES USED IN FORENSIC SCIENCE

- Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) : When broken glass is involved in a crime, putting together even tiny pieces can be key to finding important clues like the direction of bullets, the force of impact or the type of weapon used in a crime. Through its highly sensitive isotopic recognition ability, the LA-ICP-MS machine breaks glass samples of almost any size down to their atomic structure. Then, forensic scientists are able to match even the smallest shard of glass found on clothing to a glass sample from a crime scene. In order to work with this type of equipment in conjunction with forensic investigation, a Bachelor’s Degree in Forensic Science is usually necessary.

- Alternative Light Photography : For a forensic nurse, being able to quickly ascertain how much physical damage a patient has suffered can be the difference between life and death. Although they have many tools at their disposal to help make these calls quickly and accurately, Alternative Light Photography is one of the coolest tools to help see damage even before it is visible on the skin. A camera such as the Omnichrome uses blue light and orange filters to clearly show bruising below the skin’s surface. In order to use this equipment, you would need a MSN in Forensic Nursing.

- High-Speed Ballistics Photography : You might not think of it right away as a tool for forensic scientists, but ballistics specialists often use high-speed cameras in order to understand how bullet holes, gunshot wounds and glass shatters are created. Virtually anyone, from a crime scene investigator to a firearms examiner, can operate a high-speed camera without any additional education or training. Being able to identify and match bullet trajectories, impact marks and exit wounds must be done by someone with at least a Bachelor’s of Science in Forensic Science.

- Video Spectral Comparator 2000 : For crime scene investigators and forensic scientists, this is one of the most valuable forensic technologies available anywhere. With this machine, scientists and investigators can look at a piece of paper and see obscured or hidden writing, determine quality of paper and origin and “lift” indented writing. It is sometimes possible to complete these analyses even after a piece of paper has been so damaged by water or fire that it looks unintelligible to the naked eye. In order to run this equipment, at least a Bachelors degree in Forensic Science or a Master’s Degree in Document Analysis is usually required.

- Digital Surveillance For Xbox (XFT Device) : Most people don’t consider a gaming system a potential place for hiding illicit data, which is why criminals have come to use them so much. In one of the most ground-breaking forensic technologies for digital forensic specialists, the XFT is being developed to allow authorities visual access to hidden files on the Xbox hard drive. The XFT is also set up to record access sessions to be replayed in real time during court hearings. In order to be able to access and interpret this device, a Bachelor’s Degree in Computer Forensics is necessary.

- 3D Forensic Facial Reconstruction : Although this forensic technology is not considered the most reliable, it is definitely one of the most interesting available to forensic pathologists, forensic anthropologists and forensic scientists. In this technique, 3D facial reconstruction software takes a real-life human remains and extrapolates a possible physical appearance. In order to run this type of program, you should have a Bachelor’s Degree in Forensic Science, a Master’s Degree in Forensic Anthropology or a Medical Degree with an emphasis on Forensic Examination and Pathology.

- DNA Sequencer : Most people are familiar with the importance of DNA testing in the forensic science lab. Still, most people don’t know exactly what DNA sequencers are and how they may be used. Most forensic scientists and crime lab technicians use what’s called DNA profiling to identify criminals and victims using trace evidence like hair or skin samples. In cases where those samples are highly degraded, however, they often turn to the more powerful DNA sequencer, which allows them to analyze old bones or teeth to determine the specific ordering of a person’s DNA nucleobases, and generate a “read” or a unique DNA pattern that can help identify that person as a possible suspect or criminal.

- Forensic Carbon-14 Dating : Carbon dating has long been used to identify the age of unknown remains for anthropological and archaeological findings. Since the amount of radiocarbon (which is calculated in a Carbon-14 dating) has increased and decreased to distinct levels over the past 50 years, it is now possible to use this technique to identify forensic remains using this same tool. The only people in the forensic science field that have ready access to Carbon-14 Dating equipment are forensic scientists, usually with a Master’s Degree in Forensic Anthropology or Forensic Archaeology.

- Magnetic Fingerprinting and Automated Fingerprint Identification (AFIS) : With these forensic technologies, crime scene investigators, forensic scientists and police officers can quickly and easily compare a fingerprint at a crime scene with an extensive virtual database. In addition, the incorporation of magnetic fingerprinting dust and no-touch wanding allows investigators to get a perfect impression of fingerprints at a crime scene without contamination. While using AFIS requires only an Associates Degree in Law Enforcement, magnetic fingerprinting usually requires a Bachelor’s Degree in Forensic Science or Crime Scene Investigation.

- Link Analysis Software for Forensic Accountants : When a forensic accountant is trying to track illicit funds through a sea of paperwork, link analysis software is an invaluable tool to help highlight strange financial activity. This software combines observations of unusual digital financial transactions, customer profiling and statistics to generate probabilities of illegal behavior. In order to accurately understand and interpret findings with this forensic technology, a Master’s Degree in Forensic Accounting is necessary.

METHODOLOGY FOR THE FEATURED FORENSIC SCIENCE TECHNOLOGIES

When deciding which technologies to include on this list, a number of factors were taken into consideration.

- Relevance to the Topic of Forensic Technology: The said technology must be actively used in the field of Forensic Science and can be taught at the college level. Widely regarded technologies were considered first, while more experimental technologies were included only on the basis of reputable peer-reviewed documentation.

- Novelty in the Field of Forensic Science: More experimental technologies were given higher priority based on whether the technology gave advanced information that is not readily available by using other technologies. These “cutting-edge” technologies were thoroughly vetted to ensure that they have become accepted techniques by leaders in the field.

- Reliability of Technology: Finally, only techniques used with more than 80% reliability were included in this list. Factors that affect reliability included case closure rate, successful conviction rate and correct identification rate.

Sources:

Writer: Willow Dawn Becker: Willow is a blogger, parent, former educator and regular contributor to www.forensicscolleges.com. When she's not writing about forensic science, you'll find her blogging about education online, or enjoying the beauty of Oregon.

The American Mafia, including a List of Italian Mafia Crime Families in the United States

YouTube Video of the Movie Trailer for Goodfellas (1990)

Pictured: Movie Posters from two of the greatest Mafia Movies of all time: (L) "The Godfather" (1972); "Goodfellas" (1990)

The American Mafia (commonly shortened to the Mafia or the Mob, though “the Mob" can refer to other organized crime groups) or Italian-American Mafia, is a highly organized Italian-American criminal society.

The organization is often referred to by members as Cosa Nostra (Italian pronunciation: our thing) and by the government as La Cosa Nostra (LCN).

The organization's name is derived from the original Mafia or Cosa nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, and it originally emerged as an offshoot of the Sicilian Mafia; however, the organization eventually encompassed or absorbed other Italian-American gangsters and Italian-American crime groups (such as the American Camorra) living in the United States and Canada that are not of Sicilian origin. It is often colloquially referred to as the Italian Mafia or Italian Mob, though these terms may also apply to the separate yet related organized crime groups in Italy.

The Mafia in the United States emerged in impoverished Italian immigrant neighborhoods or ghettos in New York's East Harlem (or Italian Harlem), Lower East Side, and Brooklyn. It also emerged in other areas of the East Coast of the United States and several other major metropolitan areas (such as New Orleans and Chicago) during the late 19th century and early 20th century, following waves of Italian immigration especially from Sicily and other regions of Southern Italy.

The Mafie has its roots in the Sicilian Mafia but is a separate organization in the United States. Neapolitan, Calabrian, and other Italian criminal groups in the U.S., as well as independent Italian-American criminals, eventually merged with Sicilian Mafiosi to create the modern pan-Italian Mafia in North America.

Today, the American Mafia cooperates in various criminal activities with Italian organized crime groups, such as the Sicilian Mafia, the Camorra of Naples, and 'Ndrangheta of Calabria. The most important unit of the American Mafia is that of a "family," as the various criminal organizations that make up the Mafia are known. Despite the name of "family" to describe the various units, they are not familial groupings.

The Mafia is currently most active in the northeastern United States, especially in New York City, Philadelphia, New Jersey, Buffalo and New England, in areas such as Boston, Providence and Hartford.

The Mafia is also heavily active in Chicago and other large Midwestern cities such as Detroit, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Cleveland, St. Louis, Kansas City as well as in New Orleans, Florida, Las Vegas and Los Angeles, with smaller families, associates, and crews in other parts of the country.

At the Mafia's peak, there were at least 26 cities around the United States with Cosa Nostra families, with many more offshoots and associates in other cities. There are five main New York City Mafia families, known as the Five Families: the Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Bonanno, and Colombo families.

At its peak, the Mafia dominated organized crime in the United States. Each crime family has its own territory (except for the Five Families) and operates independently, while nationwide coordination is overseen by the Commission, which consists of the bosses of each of the strongest families.

Today, most of the Mafia's activities are contained to the northeastern United States and Chicago, where they continue to dominate organized crime, despite the increasing numbers of other crime groups.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The American Mafia:

List of Italian-American Mafia Families in the United States

According to the 2004 New Jersey State Commission of Investigation there were 24 active Mafia families in the United States. In 2004, author Thomas Milhorn reported that the Mafia was active in 26 cities across the United States:

Northeastern United States:

New York:

Southern United States:

Alabama:

Western United States:

California:

The organization is often referred to by members as Cosa Nostra (Italian pronunciation: our thing) and by the government as La Cosa Nostra (LCN).

The organization's name is derived from the original Mafia or Cosa nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, and it originally emerged as an offshoot of the Sicilian Mafia; however, the organization eventually encompassed or absorbed other Italian-American gangsters and Italian-American crime groups (such as the American Camorra) living in the United States and Canada that are not of Sicilian origin. It is often colloquially referred to as the Italian Mafia or Italian Mob, though these terms may also apply to the separate yet related organized crime groups in Italy.

The Mafia in the United States emerged in impoverished Italian immigrant neighborhoods or ghettos in New York's East Harlem (or Italian Harlem), Lower East Side, and Brooklyn. It also emerged in other areas of the East Coast of the United States and several other major metropolitan areas (such as New Orleans and Chicago) during the late 19th century and early 20th century, following waves of Italian immigration especially from Sicily and other regions of Southern Italy.

The Mafie has its roots in the Sicilian Mafia but is a separate organization in the United States. Neapolitan, Calabrian, and other Italian criminal groups in the U.S., as well as independent Italian-American criminals, eventually merged with Sicilian Mafiosi to create the modern pan-Italian Mafia in North America.

Today, the American Mafia cooperates in various criminal activities with Italian organized crime groups, such as the Sicilian Mafia, the Camorra of Naples, and 'Ndrangheta of Calabria. The most important unit of the American Mafia is that of a "family," as the various criminal organizations that make up the Mafia are known. Despite the name of "family" to describe the various units, they are not familial groupings.

The Mafia is currently most active in the northeastern United States, especially in New York City, Philadelphia, New Jersey, Buffalo and New England, in areas such as Boston, Providence and Hartford.

The Mafia is also heavily active in Chicago and other large Midwestern cities such as Detroit, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Cleveland, St. Louis, Kansas City as well as in New Orleans, Florida, Las Vegas and Los Angeles, with smaller families, associates, and crews in other parts of the country.

At the Mafia's peak, there were at least 26 cities around the United States with Cosa Nostra families, with many more offshoots and associates in other cities. There are five main New York City Mafia families, known as the Five Families: the Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Bonanno, and Colombo families.

At its peak, the Mafia dominated organized crime in the United States. Each crime family has its own territory (except for the Five Families) and operates independently, while nationwide coordination is overseen by the Commission, which consists of the bosses of each of the strongest families.

Today, most of the Mafia's activities are contained to the northeastern United States and Chicago, where they continue to dominate organized crime, despite the increasing numbers of other crime groups.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The American Mafia:

- Usage of the term Mafia

- History

- Structure

- Rituals

- Cooperation with the U.S. government

- Law enforcement and the Mafia

- In popular culture

- See also:

- March 14, 1891 lynchings

- Atlantic City Conference

- Havana Conference

- Irish Mob

- Jewish-American organized crime

- Greek mafia

- Sicilian mafia

- Timeline of organized crime

- Triad ("Chinese Mafia")

- Unione Corse ("Corsican Mafia")

- Yakuza

- Gangrule, American Mafia history

- Italian Mafia Terms Defined

- The 26 Original American Mafia Families – AmericanMafia.com

- Mafia Today daily updated mafia news site and Mafia resource

List of Italian-American Mafia Families in the United States

According to the 2004 New Jersey State Commission of Investigation there were 24 active Mafia families in the United States. In 2004, author Thomas Milhorn reported that the Mafia was active in 26 cities across the United States:

Northeastern United States:

New York:

- The Five Families – operate in New York City, the New York Metropolitan area, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Florida, California and Nevada.

- Buffalo crime family (Magaddino family)

- Rochester crime family – defunct

- Philadelphia crime family (Bruno family)

- Bufalino crime family (Pittston, Wilkes-Barre, Scranton and the Wyoming Valley area) – nearly defunct

- Pittsburgh crime family (LaRocca family)

- Patriarca crime family (Boston/Providence and Connecticut areas)

- Detroit Partnership (Zerilli family)

- Kansas City crime family (Civella family)

- St. Louis crime family (Giordano family)

- Cleveland crime family (Porrello family)

- Milwaukee crime family (Balistrieri family)

Southern United States:

Alabama:

- Birmingham crime family – defunct since 1938

- Trafficante crime family (Tampa area)

- The Five Families of New York have crews operating in South Florida

- Bonanno crime family – is operating in South Florida

- Colombo crime family's Florida faction – is operating in South Florida

- Gambino crime family's Florida faction – is operating in South Florida and the Tampa Bay Area.

- Genovese crime family – is operating in South Florida. See soldier Albert Facchiano

- Lucchese crime family – is operating in South Florida and Central Florida Counties of Pasco and Pinellas.

- New Orleans crime family (Marcello family) – nearly defunct

- Dallas crime family (Civello family) – defunct

- Houston crime family – defunct

Western United States:

California:

- Dragna crime family (Los Angeles area)

- San Francisco crime family (Lanza family) – defunct

- San Jose crime family (Cerrito family) – defunct

- Las Vegas is considered open territory allowing all crime families to operate in the city's Casinos. Since the 1930s, the Los Angeles families, the Five Families of New York and the Midwest families have owned and operated in Casinos in the Las Vegas Strip.

- Denver crime family (Smaldone family) – defunct

- Seattle crime family (Colacurcio family)

Crime in the United States, including Organized Crime Groups

YouTube Video of the Movie Trailer from "The Untouchables" (1987)

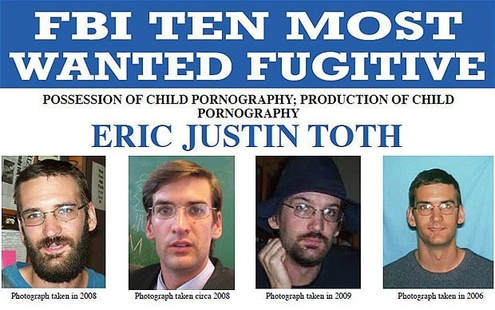

Pictured: 'Child pornographer' replaces Osama bin Laden on FBI 10 Most Wanted List (April 10, 2002)

Click here for a List of Organized Crime Groups in the United States.

Crime in the United States has been recorded since colonization. Crime rates have varied over time, with a sharp rise after 1963, reaching a broad peak between the 1970s and early 1990s. Since then, crime has declined significantly in the United States, and current crime rates are approximately the same as those of the 1960s.

Statistics on specific crimes are indexed in the annual Uniform Crime Reports by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and by annual National Crime Victimization Surveys by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

In addition to the primary Uniform Crime Report known as Crime in the United States, the FBI publishes annual reports on the status of law enforcement in the United States. The report's definitions of specific crimes are considered standard by many American law enforcement agencies.

According to the FBI, index crime in the United States includes violent crime and property crime. Violent crime consists of four criminal offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault; property crime consists of burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, and arson.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Crime in the United States:

Crime in the United States has been recorded since colonization. Crime rates have varied over time, with a sharp rise after 1963, reaching a broad peak between the 1970s and early 1990s. Since then, crime has declined significantly in the United States, and current crime rates are approximately the same as those of the 1960s.

Statistics on specific crimes are indexed in the annual Uniform Crime Reports by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and by annual National Crime Victimization Surveys by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

In addition to the primary Uniform Crime Report known as Crime in the United States, the FBI publishes annual reports on the status of law enforcement in the United States. The report's definitions of specific crimes are considered standard by many American law enforcement agencies.

According to the FBI, index crime in the United States includes violent crime and property crime. Violent crime consists of four criminal offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault; property crime consists of burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, and arson.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Crime in the United States:

- Crime over time

- Arrests

- Characteristics of offenders

- Crime victimology

- Incarceration

- International comparison

- Geography of crime

- Number and growth of criminal laws

- See also:

- Incarceration in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- National Crime Information Center Interstate Identification Index

- United States cities by crime rate

- List of U.S. states by homicide rate

- Strict liability (criminal) § United States

- Contempt of court § United States

- 15 Most Wanted by U.S. Marshals

- The FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives

- Surviving Crime

- Latest Crime Stats Released (FBI)

- DEA Fugitives, Major International Fugitives

- New York State's 100 Most Wanted Fugitives

- All Most Wanted - official website of the Los Angeles Police Department

- Nationmaster - Worldwide statistics

- Open data on US violent crime

- Top 10 cities in USA with lowest recorded crime rates

- U. S. Crime and Imprisonment Statistics Total and by State from 1960 - Current

Gangs in the United States

YouTube Video of the Movie Trailer "The Wild One": The Fight Scene (1953)*

* --"Wild One" 1953

Pictured: Street Gangs & Human Trafficking - A Growing Threat

Gangs in the United States include several types of groups, including the following:

Approximately 1.4 million people were part of gangs as of 2011, and more than 33,000 gangs were active in the United States.

Many American gangs began, and still exist, in urban areas. In many cases, national street gangs originated in major cities such as New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Miami and they later migrated to other American cities.

Reasons for Joining:

People join gangs for various reasons, including:

Studies aimed at preventing youth involvement in gangs have identified additional "risk factors" for joining, including:

Gang membership was also associated with:

Activities and Types of Gangs:

American gangs are responsible for an average of 48% of violent crime in most jurisdictions, and up to 90% in other jurisdictions. Major urban areas and their suburban surroundings experience the majority of gang activity, particularly gang-related violent crime.

Gangs are known to engage in traditionally gang-related gambling, drug trafficking, and arms trafficking, white collar crime such as counterfeiting, identity theft, and fraud, and non-traditional activity of human trafficking and prostitution.

Gangs can be categorized based on their ethnic affiliation, their structure, or their membership. Among the gang types defined by the National Gang Intelligence Center are the national street gang, the prison gang, the motorcycle gang, and the local street gang.

Prison gangs:

Main article: Prison gangs in the United States

American prison gangs, like most street gangs, are formed for protection against other gangs. The goal of many street gang members is to gain the respect and protection that comes from being in a prison gang. Prison gangs use street gangs members as their power base for which they recruit new members. For many members, reaching prison gang status shows the ultimate commitment to the gang.

Some prison gangs are transplanted from the street, and in some occasions, prison gangs "outgrow" the penitentiary and engage in criminal activities on the outside. Many prison gangs are racially oriented. Gang umbrella organizations like the Folk Nation and People Nation have originated in prisons.

One notable American prison gang is the Aryan Brotherhood, an organization known for its violence and white supremacist views. Established in the mid-1960s, the gang was not affiliated with the Aryan Nations and allegedly engages in violent crime, drug trafficking, and illegal gambling activities both in and out of prisons. On July 28, 2006, after a six-year federal investigation, four leaders of the gang were convicted of racketeering, murder, and conspiracy charges.

Another significant American prison gang is the Aryan League, which was formed by an alliance between the Aryan Brotherhood and Public Enemy No. 1. Working collaboratively, the gangs engage in drug trafficking, identity theft, and other white collar crime using contacts in the banking system. The gang has used its connections in the banking system to target law enforcement agencies and family members of officers.

There has been a long running racial tension between black and Hispanic prison gangs, as well as significant prison riots in which gangs have targeted each other.

Motorcycle Gangs:

The United States has a significant population of motorcycle gangs, which are groups that use motorcycle clubs as organizational structures for conducting criminal activity. Some motorcycle clubs are exclusively motorcycle gangs, while others are only partially compromised by criminal activity.

The National Gang Intelligence Center reports on all motorcycle clubs with gang activity, while other government agencies, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) focus on motorcycle clubs exclusively dedicated to gang activity. The ATF estimates that approximately 300 exclusively gang-oriented motorcycle clubs exist in the United States.

Organized crime gangs:

Main article: Organized crime

Organized criminal groups are a subtype of gang with a hierarchical leadership structure and in which individuals commit crime for personal gain. For most organized criminal group members, criminal activities constitute their occupation. There are numerous organized criminal groups with operations in the United States (including transnational organized crime groups), including the following:

The activities of organized criminal groups are highly varied, and include drug, weapons, and human trafficking (including prostitution and kidnapping), art theft, murder (including contract killings and assassinations), copyright infringement, counterfeiting, identity theft, money laundering, extortion, illegal gambling, and terrorism.

The complexity and seriousness of the crimes committed by global crime groups pose a threat not only to law enforcement but to democracy and legitimate economic development as well.

American national and local street gangs will collaborate with organized criminal groups.

Juvenile gangs:

Youth gangs are composed of young people, male or female, and like most street gangs, are either formed for protection or for social and economic reasons. Some of the most notorious and dangerous gangs have evolved from youth gangs. During the late 1980s and early 1990s an increase in violence in the United States took place and this was due primarily to an increase in violent acts committed by people under the age of 20.

Due to gangs spreading to suburban and smaller communities youth gangs are now more prevalent and exist in all regions of the United States.

Youth gangs have increasingly been creating problems in school and correctional facilities. However youth gangs are said to be an important social institution for low income youths and young adults because they often serve as cultural, social, and economic functions which are no longer served by the family, school or labor market.

Youth gangs tend to emerge during times of rapid social change and instability. Young people can be attracted to joining a youth gang for a number of reasons. They provide a degree of order and solidarity for their members and make them feel like part of a group or a community.

The diffusion of gang culture to the point where it has been integrated into a larger youth culture has led to widespread adoption by youth of many of the symbols of gang life. For this reason, more and more youth who earlier may have not condoned gang behavior are more willing, even challenged to experiment with gang-like activity.

Youth Gangs may be an ever-present feature of urban culture that change over time in its form, social meaning and antisocial behavior. However, in the United States, youth gangs have taken an especially disturbing form and continue to permeate society.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Gangs in the United States:

- national street gangs,

- local street gangs,

- prison gangs,

- motorcycle clubs,

- and ethnic and organized crime gangs.

Approximately 1.4 million people were part of gangs as of 2011, and more than 33,000 gangs were active in the United States.

Many American gangs began, and still exist, in urban areas. In many cases, national street gangs originated in major cities such as New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Miami and they later migrated to other American cities.

Reasons for Joining:

People join gangs for various reasons, including:

- Profiting from organized crime, which could be a means to obtain food and shelter, or access to luxury goods and services

- Protection from rival gangs or violent crime in general, especially when the police are distrusted or ineffective

- Personal status

- A sense of family, identity, or belonging

- Intimidation by gang members or pressure from friends

- Family tradition

- Excitement of risk-taking

Studies aimed at preventing youth involvement in gangs have identified additional "risk factors" for joining, including:

- Lack of parental supervision

- Family instability

- Family members with violent attitudes

- Being part of a socially marginalized group (e.g. ethnic minority)

- Family poverty

- Lack of youth jobs

- Academic problems (frustration at low performance, low expectations, poor personal relationships with teachers, learning disability)

- Violent crime committed by others against the potential gang member, or friends or family

- Involvement in non-gang illegal activity, especially violent crime or drug use

- Low self-esteem

- Lack of role models

- Hyperactivity

Gang membership was also associated with:

- Early sexual activity

- Illegal gun ownership

Activities and Types of Gangs:

American gangs are responsible for an average of 48% of violent crime in most jurisdictions, and up to 90% in other jurisdictions. Major urban areas and their suburban surroundings experience the majority of gang activity, particularly gang-related violent crime.

Gangs are known to engage in traditionally gang-related gambling, drug trafficking, and arms trafficking, white collar crime such as counterfeiting, identity theft, and fraud, and non-traditional activity of human trafficking and prostitution.

Gangs can be categorized based on their ethnic affiliation, their structure, or their membership. Among the gang types defined by the National Gang Intelligence Center are the national street gang, the prison gang, the motorcycle gang, and the local street gang.

Prison gangs:

Main article: Prison gangs in the United States

American prison gangs, like most street gangs, are formed for protection against other gangs. The goal of many street gang members is to gain the respect and protection that comes from being in a prison gang. Prison gangs use street gangs members as their power base for which they recruit new members. For many members, reaching prison gang status shows the ultimate commitment to the gang.

Some prison gangs are transplanted from the street, and in some occasions, prison gangs "outgrow" the penitentiary and engage in criminal activities on the outside. Many prison gangs are racially oriented. Gang umbrella organizations like the Folk Nation and People Nation have originated in prisons.

One notable American prison gang is the Aryan Brotherhood, an organization known for its violence and white supremacist views. Established in the mid-1960s, the gang was not affiliated with the Aryan Nations and allegedly engages in violent crime, drug trafficking, and illegal gambling activities both in and out of prisons. On July 28, 2006, after a six-year federal investigation, four leaders of the gang were convicted of racketeering, murder, and conspiracy charges.

Another significant American prison gang is the Aryan League, which was formed by an alliance between the Aryan Brotherhood and Public Enemy No. 1. Working collaboratively, the gangs engage in drug trafficking, identity theft, and other white collar crime using contacts in the banking system. The gang has used its connections in the banking system to target law enforcement agencies and family members of officers.

There has been a long running racial tension between black and Hispanic prison gangs, as well as significant prison riots in which gangs have targeted each other.

Motorcycle Gangs:

The United States has a significant population of motorcycle gangs, which are groups that use motorcycle clubs as organizational structures for conducting criminal activity. Some motorcycle clubs are exclusively motorcycle gangs, while others are only partially compromised by criminal activity.

The National Gang Intelligence Center reports on all motorcycle clubs with gang activity, while other government agencies, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) focus on motorcycle clubs exclusively dedicated to gang activity. The ATF estimates that approximately 300 exclusively gang-oriented motorcycle clubs exist in the United States.

Organized crime gangs:

Main article: Organized crime

Organized criminal groups are a subtype of gang with a hierarchical leadership structure and in which individuals commit crime for personal gain. For most organized criminal group members, criminal activities constitute their occupation. There are numerous organized criminal groups with operations in the United States (including transnational organized crime groups), including the following:

- the Sinaloa Cartel,

- American Mafia,

- Jewish Mafia,

- Triad Society,

- Russian Mafia,

- Yakuza,

- Korean Mafia,

- Sicilian Mafia,

- Irish Mob,

- and Albanian Mafia.

The activities of organized criminal groups are highly varied, and include drug, weapons, and human trafficking (including prostitution and kidnapping), art theft, murder (including contract killings and assassinations), copyright infringement, counterfeiting, identity theft, money laundering, extortion, illegal gambling, and terrorism.

The complexity and seriousness of the crimes committed by global crime groups pose a threat not only to law enforcement but to democracy and legitimate economic development as well.

American national and local street gangs will collaborate with organized criminal groups.

Juvenile gangs:

Youth gangs are composed of young people, male or female, and like most street gangs, are either formed for protection or for social and economic reasons. Some of the most notorious and dangerous gangs have evolved from youth gangs. During the late 1980s and early 1990s an increase in violence in the United States took place and this was due primarily to an increase in violent acts committed by people under the age of 20.

Due to gangs spreading to suburban and smaller communities youth gangs are now more prevalent and exist in all regions of the United States.

Youth gangs have increasingly been creating problems in school and correctional facilities. However youth gangs are said to be an important social institution for low income youths and young adults because they often serve as cultural, social, and economic functions which are no longer served by the family, school or labor market.

Youth gangs tend to emerge during times of rapid social change and instability. Young people can be attracted to joining a youth gang for a number of reasons. They provide a degree of order and solidarity for their members and make them feel like part of a group or a community.

The diffusion of gang culture to the point where it has been integrated into a larger youth culture has led to widespread adoption by youth of many of the symbols of gang life. For this reason, more and more youth who earlier may have not condoned gang behavior are more willing, even challenged to experiment with gang-like activity.

Youth Gangs may be an ever-present feature of urban culture that change over time in its form, social meaning and antisocial behavior. However, in the United States, youth gangs have taken an especially disturbing form and continue to permeate society.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Gangs in the United States:

- Demographics

- History

- See also:

- Crime in the United States

- National Gang Threat Assessment report by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- "Street Gang Alliance Guide" (Chicago, IL: Stream by Chicago Gang History)

"Donald Trump linked to Russian and Italian Mafias, Fusion GPS Founder claims in testimony" (by Newsweek January 19, 2018) including The Russian Mafia (Wikipedia)

YouTube Video: Report: "Russian Mob Money Helped Build Donald Trump Business Empire" (Reported By Brian Williams on The 11th Hour on MSNBC)

Pictured: Testimony from Fusion GPS co-founder Glenn Simpson alleges that President Donald Trump, shown with Russian President Vladimir Putin, had ties to the Russian mafia during his real estate development days. A transcript detailing Simpson's testimony was released Thursday.

Newsweek Article:

"Donald Trump had links to the Russian mafia during his time as a real estate developer, according to the founder of the company behind the infamous dossier alleging ties between the president and Russia.

Related: Read full text: Trump dossier started because Trump said some weird things about Putin, says Fusion GPS

Glenn Simpson, whose company Fusion GPS was hired to investigate the president, told the House Intelligence Committee in November that Trump had connections to Italian and Russian organized crime, according to a transcript released Thursday.

"We also had sort of more broadly learned that Mr. Trump had longtime associations with Italian organized crime figures," Simpson said. “And as we pieced together the early years of his biography, it seemed as if during the early part of his career he had connections to a lot of Italian Mafia figures, and then gradually during the ’90s became associated with Russian mafia figures.”

Simpson commissioned former British spy Christopher Steele to look into Trump because the president, he said, allegedly had “gone over [to Russia] a bunch of times, he said some weird things about Putin, but doesn't seem to have gotten any business deals.”

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Simpson was hired to probe the president by a conservative website, The Washington Free Beacon. After the Beacon moved on, the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton's campaign then stepped in to keep paying for the investigation. In 2016, Steele later handed over his findings included in the dossier to the FBI.

“We also increasingly saw that Mr. Trump’s business career had evolved over the prior decade into a lot of projects in overseas places, particularly in the former Soviet Union, that were very opaque, and that he had made a number of trips to Russia but said he’d never done a business deal there,” Simpson said. “And I found that mysterious.”

The dossier was one of the findings that raised questions about Trump's relationship with the Kremlin and whether Russia interfered in the 2016 presidential election.

During his testimony, Simpson said members of the Russian mafia were buying the president's properties. Democratic Representative Adam Schiff asked Simpson whether the Russian government knew about Trump's business dealings. Simpson responded with a "yes."

"If people who seem to be associated with the Russian mafia are buying Trump properties or arranging for other people to buy Trump properties, it does raise a question about whether they're doing it on behalf of the government," he later said.

During his testimony, Simpson urged the committee to continue its investigation into the president.

"I think that the evidence that has developed over the last year, since President Trump took office, is that there is a well-established pattern of surreptitious contacts that occurred last year that supports the broad allegation of some sort of an undisclosed political or financial relationship between the Trump Organization and people in Russia," he said."

[End of Newsweek Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

The Russian Mafia (Wikipedia)

[Your Web Host: note that I am excerpting those portions that are related to the activities of the Russian Mafia in the United States]

Russian organized crime, or Russian mafia, is the most powerful mafia organization in the world.

The Russian Mafia is a collective of various organized crime elements originating in the former Soviet Union.

Organized crime in Russia began in the imperial period of the Tsars, but it was not until the Soviet era that vory v zakone ("thieves-in-law") emerged as leaders of prison groups in gulags (Soviet prison labor camps), and their honor code became more defined.

With the end of World War II, the death of Joseph Stalin, and the fall of the Soviet Union, more gangs emerged in a flourishing black market, exploiting the unstable governments of the former Republics, and at its highest point, even controlling as much as two-thirds of the Russian economy.

Louis Freeh, former director of the FBI, said that the Russian mafia posed the greatest threat to U.S. national security in the mid-1990s.

In modern times, there are as many as 6,000 different groups, with more than 200 of them having a global reach.

Criminals of these various groups are either former prison members, corrupt officials and business leaders, people with ethnic ties, or people from the same region with shared criminal experiences and leaders.

However, the existence of such groups has been debated. In December 2009, Timur Lakhonin, the head of the Russian National Central Bureau of Interpol, stated "Certainly, there is crime involving our former compatriots abroad, but there is no data suggesting that an organized structure of criminal groups comprising former Russians exists abroad", while in August 2010, Alain Bauer, a French criminologist, said that it "is one of the best structured criminal organizations in Europe, with a quasi-military operation."

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Russian Mafia and its activities in the United States:

"Donald Trump had links to the Russian mafia during his time as a real estate developer, according to the founder of the company behind the infamous dossier alleging ties between the president and Russia.

Related: Read full text: Trump dossier started because Trump said some weird things about Putin, says Fusion GPS

Glenn Simpson, whose company Fusion GPS was hired to investigate the president, told the House Intelligence Committee in November that Trump had connections to Italian and Russian organized crime, according to a transcript released Thursday.

"We also had sort of more broadly learned that Mr. Trump had longtime associations with Italian organized crime figures," Simpson said. “And as we pieced together the early years of his biography, it seemed as if during the early part of his career he had connections to a lot of Italian Mafia figures, and then gradually during the ’90s became associated with Russian mafia figures.”

Simpson commissioned former British spy Christopher Steele to look into Trump because the president, he said, allegedly had “gone over [to Russia] a bunch of times, he said some weird things about Putin, but doesn't seem to have gotten any business deals.”

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Simpson was hired to probe the president by a conservative website, The Washington Free Beacon. After the Beacon moved on, the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton's campaign then stepped in to keep paying for the investigation. In 2016, Steele later handed over his findings included in the dossier to the FBI.

“We also increasingly saw that Mr. Trump’s business career had evolved over the prior decade into a lot of projects in overseas places, particularly in the former Soviet Union, that were very opaque, and that he had made a number of trips to Russia but said he’d never done a business deal there,” Simpson said. “And I found that mysterious.”

The dossier was one of the findings that raised questions about Trump's relationship with the Kremlin and whether Russia interfered in the 2016 presidential election.

During his testimony, Simpson said members of the Russian mafia were buying the president's properties. Democratic Representative Adam Schiff asked Simpson whether the Russian government knew about Trump's business dealings. Simpson responded with a "yes."

"If people who seem to be associated with the Russian mafia are buying Trump properties or arranging for other people to buy Trump properties, it does raise a question about whether they're doing it on behalf of the government," he later said.

During his testimony, Simpson urged the committee to continue its investigation into the president.

"I think that the evidence that has developed over the last year, since President Trump took office, is that there is a well-established pattern of surreptitious contacts that occurred last year that supports the broad allegation of some sort of an undisclosed political or financial relationship between the Trump Organization and people in Russia," he said."

[End of Newsweek Article]

___________________________________________________________________________

The Russian Mafia (Wikipedia)

[Your Web Host: note that I am excerpting those portions that are related to the activities of the Russian Mafia in the United States]

Russian organized crime, or Russian mafia, is the most powerful mafia organization in the world.

The Russian Mafia is a collective of various organized crime elements originating in the former Soviet Union.

Organized crime in Russia began in the imperial period of the Tsars, but it was not until the Soviet era that vory v zakone ("thieves-in-law") emerged as leaders of prison groups in gulags (Soviet prison labor camps), and their honor code became more defined.

With the end of World War II, the death of Joseph Stalin, and the fall of the Soviet Union, more gangs emerged in a flourishing black market, exploiting the unstable governments of the former Republics, and at its highest point, even controlling as much as two-thirds of the Russian economy.

Louis Freeh, former director of the FBI, said that the Russian mafia posed the greatest threat to U.S. national security in the mid-1990s.

In modern times, there are as many as 6,000 different groups, with more than 200 of them having a global reach.

Criminals of these various groups are either former prison members, corrupt officials and business leaders, people with ethnic ties, or people from the same region with shared criminal experiences and leaders.

However, the existence of such groups has been debated. In December 2009, Timur Lakhonin, the head of the Russian National Central Bureau of Interpol, stated "Certainly, there is crime involving our former compatriots abroad, but there is no data suggesting that an organized structure of criminal groups comprising former Russians exists abroad", while in August 2010, Alain Bauer, a French criminologist, said that it "is one of the best structured criminal organizations in Europe, with a quasi-military operation."

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Russian Mafia and its activities in the United States:

Law of the United States including the LexisNexis Legal Database

YouTube Video: Lexis Practice Advisor® Overview - Show Me How Video Series

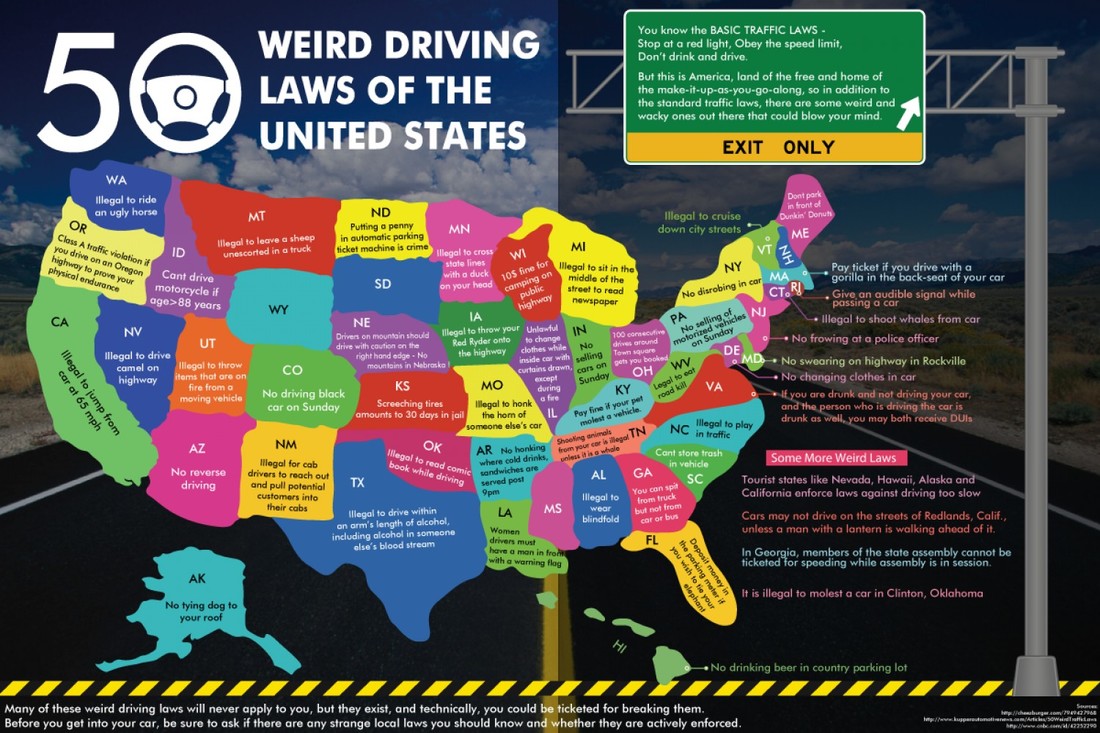

Pictured below: 50 Weird Driving Laws of the United States

LexisNexis Group is a corporation providing computer-assisted legal research as well as business research and risk management services. During the 1970s, LexisNexis pioneered the electronic accessibility of legal and journalistic documents.

As of 2006, the company has the world's largest electronic database for legal and public-records related information.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the LexisNexis Group:

Law of the United States comprises many levels of codified forms of law, of which the most important is the United States Constitution, the foundation of the federal government of the United States.

The Constitution sets out the boundaries of federal law, which consists of acts of Congress, treaties ratified by the Senate, regulations promulgated by the executive branch, and case law originating from the federal judiciary.

The United States Code is the official compilation and codification of general and permanent federal statutory law.

Federal law and treaties, so long as they are in accordance with the Constitution, preempt conflicting state and territorial laws in the 50 U.S. states and in the territories.

However, the scope of federal preemption is limited because the scope of federal power is not universal. In the dual-sovereign system of American federalism (actually tripartite because of the presence of Indian reservations), states are the plenary sovereigns, each with their own constitution, while the federal sovereign possesses only the limited supreme authority enumerated in the Constitution.

Indeed, states may grant their citizens broader rights than the federal Constitution as long as they do not infringe on any federal constitutional rights. Thus, most U.S. law (especially the actual "living law" of contract, tort, property, criminal, and family law experienced by the majority of citizens on a day-to-day basis) consists primarily of state law, which can and does vary greatly from one state to the next.

At both the federal and state levels, with the exception of the state of Louisiana, the law of the United States is largely derived from the common law system of English law, which was in force at the time of the American Revolutionary War. However, American law has diverged greatly from its English ancestor both in terms of substance and procedure, and has incorporated a number of civil law innovations.

General Overview:

Sources of law:

In the United States, the law is derived from five sources:

Constitutionality:

Where Congress enacts a statute that conflicts with the Constitution, the Supreme Court may find that law unconstitutional and declare it invalid.

Notably, a statute does not disappear automatically merely because it has been found unconstitutional; it must be deleted by a subsequent statute. Many federal and state statutes have remained on the books for decades after they were ruled to be unconstitutional.

However, under the principle of stare decisis, no sensible lower court will enforce an unconstitutional statute, and any court that does so will be reversed by the Supreme Court.

Conversely, any court that refuses to enforce a constitutional statute (where such constitutionality has been expressly established in prior cases) will risk reversal by the Supreme Court.

American common law:

The United States and most Commonwealth countries are heirs to the common law legal tradition of English law. Certain practices traditionally allowed under English common law were expressly outlawed by the Constitution, such as bills of attainder and general search warrants.

As common law courts, U.S. courts have inherited the principle of stare decisis. American judges, like common law judges elsewhere, not only apply the law, they also make the law, to the extent that their decisions in the cases before them become precedent for decisions in future cases.

The actual substance of English law was formally "received" into the United States in several ways:

First, all U.S. states except Louisiana have enacted "reception statutes" which generally state that the common law of England (particularly judge-made law) is the law of the state to the extent that it is not repugnant to domestic law or indigenous conditions.

Some reception statutes impose a specific cutoff date for reception, such as the date of a colony's founding, while others are deliberately vague. Thus, contemporary U.S. courts often cite pre-Revolution cases when discussing the evolution of an ancient judge-made common law principle into its modern form, such as the heightened duty of care traditionally imposed upon common carriers.

Second, a small number of important British statutes in effect at the time of the Revolution have been independently reenacted by U.S. states. Two examples that many lawyers will recognize are the Statute of Frauds (still widely known in the U.S. by that name) and the Statute of 13 Elizabeth (the ancestor of the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act). Such English statutes are still regularly cited in contemporary American cases interpreting their modern American descendants.

However, it is important to understand that despite the presence of reception statutes, much of contemporary American common law has diverged significantly from English common law. The reason is that although the courts of the various Commonwealth nations are often influenced by each other's rulings, American courts rarely follow post-Revolution Commonwealth rulings unless there is no American ruling on point, the facts and law at issue are nearly identical, and the reasoning is strongly persuasive.

Early on, American courts, even after the Revolution, often did cite contemporary English cases. This was because appellate decisions from many American courts were not regularly reported until the mid-19th century; lawyers and judges, as creatures of habit, used English legal materials to fill the gap.

But citations to English decisions gradually disappeared during the 19th century as American courts developed their own principles to resolve the legal problems of the American people.

The number of published volumes of American reports soared from eighteen in 1810 to over 8,000 by 1910.

By 1879 one of the delegates to the California constitutional convention was already complaining: "Now, when we require them to state the reasons for a decision, we do not mean they shall write a hundred pages of detail. We [do] not mean that they shall include the small cases, and impose on the country all this fine judicial literature, for the Lord knows we have got enough of that already."

Today, in the words of Stanford law professor Lawrence Friedman: "American cases rarely cite foreign materials. Courts occasionally cite a British classic or two, a famous old case, or a nod to Blackstone; but current British law almost never gets any mention." Foreign law has never been cited as binding precedent, but as a reflection of the shared values of Anglo-American civilization or even Western civilization in general.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Law in the United States: See also:

As of 2006, the company has the world's largest electronic database for legal and public-records related information.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the LexisNexis Group:

- History

- Legal content offerings

- Censorship

- Other products

- Sheshunoff | Pratt

- Reception

- Awards and recognition

- See also:

Law of the United States comprises many levels of codified forms of law, of which the most important is the United States Constitution, the foundation of the federal government of the United States.

The Constitution sets out the boundaries of federal law, which consists of acts of Congress, treaties ratified by the Senate, regulations promulgated by the executive branch, and case law originating from the federal judiciary.

The United States Code is the official compilation and codification of general and permanent federal statutory law.

Federal law and treaties, so long as they are in accordance with the Constitution, preempt conflicting state and territorial laws in the 50 U.S. states and in the territories.

However, the scope of federal preemption is limited because the scope of federal power is not universal. In the dual-sovereign system of American federalism (actually tripartite because of the presence of Indian reservations), states are the plenary sovereigns, each with their own constitution, while the federal sovereign possesses only the limited supreme authority enumerated in the Constitution.

Indeed, states may grant their citizens broader rights than the federal Constitution as long as they do not infringe on any federal constitutional rights. Thus, most U.S. law (especially the actual "living law" of contract, tort, property, criminal, and family law experienced by the majority of citizens on a day-to-day basis) consists primarily of state law, which can and does vary greatly from one state to the next.

At both the federal and state levels, with the exception of the state of Louisiana, the law of the United States is largely derived from the common law system of English law, which was in force at the time of the American Revolutionary War. However, American law has diverged greatly from its English ancestor both in terms of substance and procedure, and has incorporated a number of civil law innovations.

General Overview:

Sources of law:

In the United States, the law is derived from five sources:

- constitutional law,

- statutory law,

- treaties,

- administrative regulations,

- and the common law (which includes case law).

Constitutionality:

Where Congress enacts a statute that conflicts with the Constitution, the Supreme Court may find that law unconstitutional and declare it invalid.

Notably, a statute does not disappear automatically merely because it has been found unconstitutional; it must be deleted by a subsequent statute. Many federal and state statutes have remained on the books for decades after they were ruled to be unconstitutional.

However, under the principle of stare decisis, no sensible lower court will enforce an unconstitutional statute, and any court that does so will be reversed by the Supreme Court.

Conversely, any court that refuses to enforce a constitutional statute (where such constitutionality has been expressly established in prior cases) will risk reversal by the Supreme Court.

American common law:

The United States and most Commonwealth countries are heirs to the common law legal tradition of English law. Certain practices traditionally allowed under English common law were expressly outlawed by the Constitution, such as bills of attainder and general search warrants.

As common law courts, U.S. courts have inherited the principle of stare decisis. American judges, like common law judges elsewhere, not only apply the law, they also make the law, to the extent that their decisions in the cases before them become precedent for decisions in future cases.

The actual substance of English law was formally "received" into the United States in several ways:

First, all U.S. states except Louisiana have enacted "reception statutes" which generally state that the common law of England (particularly judge-made law) is the law of the state to the extent that it is not repugnant to domestic law or indigenous conditions.

Some reception statutes impose a specific cutoff date for reception, such as the date of a colony's founding, while others are deliberately vague. Thus, contemporary U.S. courts often cite pre-Revolution cases when discussing the evolution of an ancient judge-made common law principle into its modern form, such as the heightened duty of care traditionally imposed upon common carriers.