Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

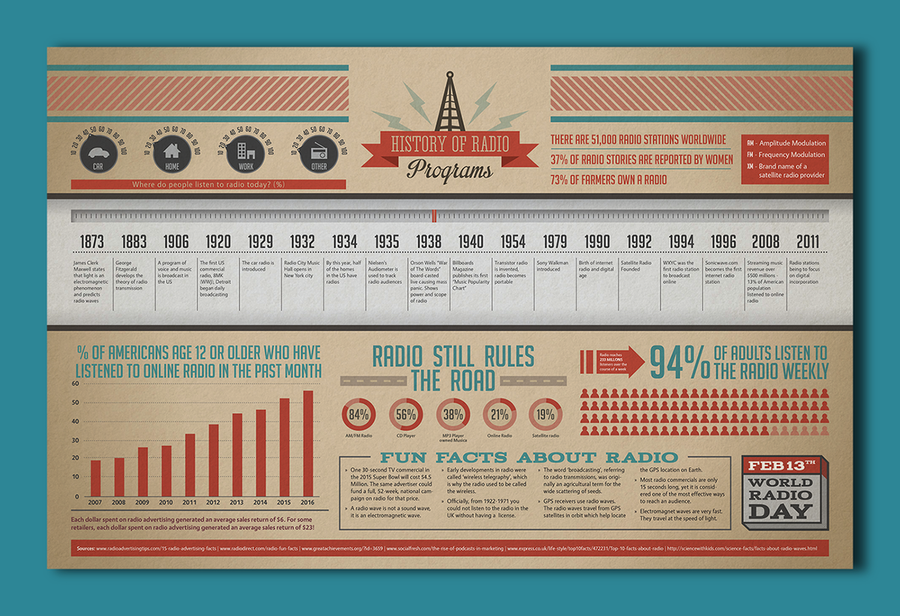

Below, we cover Radio, including FM and AM, Talk vs. Music (in all popular musical formats), Land or Satellite, with Commercials vs. Paid Radio, focusing on the United States

Radio Stations in the United States, including a List by State

as well as a Listing of Radio Formats

YouTube Video of KSHE 95 Morning Show DJ Lern being interviewed

YouTube Video: Mark and Brian (KLOS DJs) talk with Keith Richards

YouTube Video: Howard Stern and Madonna - Exclusive Video Highlights

Pictured Below, Top to Bottom:

KSHE 95 FM (St. Louis) radio morning rock show (L-R) DJs Lern, UMan and Carl the Intern

KLOS 95.5 FM: (Los Angeles) "Breakfast with the Beatles" host Chris Carter in the KLOS-FM studio in 2008.

WDHA 105.5 FM (New Jersey): Terrie Carr, left, and fellow WDHA deejay Curtis Kay are familiar voices to North Jersey rock fans.

Click here for a listing of Radio Stations by State within the United States.

Radio broadcasting in the United States is a major mass medium. Unlike radio in most other countries, American radio has historically relied primarily on commercial advertising sponsorship on for-profit stations.

The arrival of television in the 1950s forced radio into a niche role, as leading participants moved into the much larger field of television. In the 21st century, radio has been adjusting to the arrival of the Internet and Internet radio.

For a Listing of Radio Formats by format, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

Radio broadcasting in the United States is a major mass medium. Unlike radio in most other countries, American radio has historically relied primarily on commercial advertising sponsorship on for-profit stations.

The arrival of television in the 1950s forced radio into a niche role, as leading participants moved into the much larger field of television. In the 21st century, radio has been adjusting to the arrival of the Internet and Internet radio.

For a Listing of Radio Formats by format, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

- List of formats

- See also:

Golden Age of Radio

YouTube Video of the Golden Age of Radio

YouTube Video: War of the Worlds: The Panic Broadcast | PBS America

The old-time radio era, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Radio, was an era of radio programming in the United States during which radio was the dominant electronic home entertainment medium.

It began with the birth of commercial radio broadcasting in the early 1920s and lasted until the 1950s, when television superseded radio as the medium of choice for scripted programming. The last few scripted radio dramas and full-service radio stations ended in 1962.

During this period radio was the only broadcast medium, and people regularly tuned into their favorite radio programs, and families gathered to listen to the home radio in the evening. According to a 1947 C. E. Hooper survey, 82 out of 100 Americans were found to be radio listeners.

A variety of new entertainment formats and genres were created for the new medium, many of which later migrated to television: radio plays, mystery serials, soap operas, quiz shows, talent shows, variety hours, situation comedies, play-by-play sports, children's shows, cooking shows.

Since this era, radio programming has shifted to a more narrow format of news, talk, sports and music.

Origins:

The broadcasts of live drama, comedy, music and news that characterize the Golden Age of Radio had a precedent in the Théâtrophone, commercially introduced in Paris in 1890 and available as late as 1932. It allowed subscribers to eavesdrop on live stage performances and hear news reports by means of a network of telephone lines. The development of radio eliminated the wires and subscription charges from this concept.

Boy learning how to build his own radio circa 1922.On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden is said to have broadcast the first radio program, consisting of some violin playing and passages from the Bible. While Fessenden's role as an inventor and early radio experimenter is not in dispute, several contemporary radio researchers have questioned whether the Christmas Eve broadcast took place, or whether the date was in fact several weeks earlier.

The first apparent published reference to the event was made in 1928 by H.P. Davis, Vice President of Westinghouse, in a lecture given at Harvard University. In 1932 Fessenden cited the Christmas Eve 1906 broadcast event in a letter he wrote to Vice President S.M. Kinter of Westinghouse. Fessenden's wife Helen recounts the broadcast in her book Fessenden: Builder of Tomorrows (1940), eight years after Fessenden's death.

The issue of whether the 1906 Fessenden broadcast actually happened is discussed in Donna Halper's article "In Search of the Truth About Fessenden" and also in James O'Neal's essays. An annotated argument supporting Fessenden as the world's first radio broadcaster was offered in 2006 by Dr. John S. Belrose, Radioscientist Emeritus at the Communications Research Centre Canada, in his essay "Fessenden's 1906 Christmas Eve broadcast."

It was not until after the Titanic catastrophe in 1912 that radio for mass communication came into vogue, inspired first by the work of amateur ("ham") radio operators. Radio was especially important during World War I as it was vital for air and naval operations.

World War I brought about major developments in radio, superseding the Morse code of the wireless telegraph with the vocal communication of the wireless telephone, through advancements in vacuum tube technology and the introduction of the transceiver.

After the war, numerous radio stations were born in the United States and set the standard for later radio programs. The first radio news program was broadcast on August 31, 1920 on the station 8MK in Detroit; owned by The Detroit News, the station covered local election results.

This was followed in 1920 with the first commercial radio station in the United States, KDKA, being established in Pittsburgh. The first regular entertainment programs were broadcast in 1922, and on March 10, Variety carried the front-page headline: "Radio Sweeping Country: 1,000,000 Sets in Use." A highlight of this time was the first Rose Bowl being broadcast on January 1, 1923 on the Los Angeles station KHJ.

Radio networks:

Several radio networks broadcast in the United States, airing programs nationwide. Their distribution made the golden age of radio possible. The networks declined in the early 1960s; Mutual and NBC both closed down their radio operations in the 1990s, while ABC lasted until 2007 when it was bought by Citadel Broadcasting, which was in turn merged with Cumulus Media on September 16, 2011.

As of November 14, 2013, Mutual, ABC and NBC's radio assets now reside with Cumulus Media's Westwood One division through numerous mergers and acquisitions since the mid-1980s. CBS still operates its network as of 2016, which is expected to close down mid 2017 as its radio assets are in the process of being integrated with Entercom as of February 2, 2017.

The major networks were:

Types of programs:

During the Golden Age of Radio, new forms of entertainment were created for the new medium, which later migrated to television and other media, including:

In addition, the capability of the new medium to get information to people created the format of modern radio news: headlines, remote reporting, sidewalk interviews (such as Vox Pop), panel discussions, weather reports, farm reports.

The earliest radio programs of the 1920s were largely unsponsored; radio stations were a service designed to sell radio receivers. By the late 1920s, radio had reached critical mass and saturated the market, necessitating a change in business model. The sponsored musical feature soon became most popular program format.

Most early radio sponsorship came in the form of selling the naming rights to the program, as evidenced by such programs as The A&P Gypsies, Champion Spark Plug Hour, The Clicquot Club Eskimos, and King Biscuit Time. Commercials as they are known in the modern era were still relatively uncommon and considered intrusive.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the leading orchestras were heard often through big band remotes, and NBC's Monitor continued such remotes well into the 1950s by broadcasting live music from New York City jazz clubs to rural America.

Classical music programs on the air included The Voice of Firestone and The Bell Telephone Hour. Texaco sponsored the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts; the broadcasts, now sponsored by the Toll Brothers, continue to this day around the world, and are one of the few examples of live classical music still broadcast on radio.

One of the most notable of all classical music radio programs of the Golden Age of Radio featured the celebrated Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which had been created especially for him. At that time, nearly all classical musicians and critics considered Toscanini the greatest living maestro. Popular songwriters such as George Gershwin were also featured on radio. (Gershwin, in addition to frequent appearances as a guest, also had his own program in 1934.) The New York Philharmonic also had weekly concerts on radio.

There was no dedicated classical music radio station like NPR at that time, so classical music programs had to share the network they were broadcast on with more popular ones, much as in the days of television before the creation of NET and PBS.

Country music also enjoyed popularity. National Barn Dance, begun on Chicago's WLS in 1924, was picked up by NBC Radio in 1933. In 1925, WSM Barn Dance went on the air from Nashville. It was renamed the Grand Ole Opry in 1927 and NBC carried portions from 1944 to 1956. NBC also aired The Red Foley Show from 1951 to 1961, and ABC Radio carried Ozark Jubilee from 1953 to 1961.

Radio attracted top comedy talents from vaudeville and Hollywood for many years, including:

Situational comedies also gained popularity, including:

Radio comedy ran the gamut from the small town humor of Lum and Abner, Herb Shriner and Minnie Pearl to the dialect characterizations of Mel Blanc and the caustic sarcasm of Henry Morgan.

Gags galore were delivered weekly on Stop Me If You've Heard This One and Can You Top This?, panel programs devoted to the art of telling jokes.

Quiz shows were lampooned on It Pays to Be Ignorant, and other memorable parodies were presented by such satirists as Spike Jones, Stoopnagle and Budd, Stan Freberg and Bob and Ray. British comedy reached American shores in a major assault when NBC carried The Goon Show in the mid-1950s.

Some shows originated as stage productions: Clifford Goldsmith's play What a Life was reworked into NBC's popular, long-running The Aldrich Family (1939–1953) with the familiar catchphrases "Henry! Henry Aldrich!," followed by Henry's answer, "Coming, Mother!"

Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway hit, You Can't Take It with You (1936), became a weekly situation comedy heard on Mutual (1944) with Everett Sloane and later on NBC (1951) with Walter Brennan.

Other shows were adapted from comic strips, including

Bob Montana's redheaded teen of comic strips and comic books was heard on radio's Archie Andrews from 1943 to 1953. The Timid Soul was a 1941–1942 comedy based on cartoonist H. T. Webster's famed Caspar Milquetoast character, and Robert L. Ripley's Believe It or Not! was adapted to several different radio formats during the 1930s and 1940s. Conversely, some radio shows gave rise to spinoff comic strips, such as My Friend Irma starring Marie Wilson.

The first soap opera, Clara, Lu, and Em was introduced in 1930 on Chicago's WGN. When daytime serials began in the early 1930s, they became known as soap operas because many were sponsored by soap products and detergents.

The line-up of late afternoon adventure serials included

Badges, rings, decoding devices and other radio premiums offered on these adventure shows were often allied with a sponsor's product, requiring the young listeners to mail in a boxtop from a breakfast cereal or other proof of purchase.

Radio dramas were presented on such programs as the following:

Orson Welles's The Mercury Theatre on the Air and The Campbell Playhouse were considered by many critics to be the finest radio drama anthologies ever presented. They usually starred Welles in the leading role, along with celebrity guest stars such as Margaret Sullavan or Helen Hayes, in adaptations from literature, Broadway, and/or films.

They included such titles as Liliom, Oliver Twist (a title now feared lost), A Tale of Two Cities, Lost Horizon, and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. It was on Mercury Theatre that Welles presented his celebrated-but-infamous 1938 adaptation of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds, formatted to sound like a breaking news program.

Theatre Guild on the Air presented adaptations of classical and Broadway plays. Their Shakespeare adaptations included a one-hour Macbeth starring Maurice Evans and Judith Anderson, and a 90-minute Hamlet, starring John Gielgud. Recordings of many of these programs survive.

During the 1940s, Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, famous for playing Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in films, repeated their characterizations on radio on The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which featured both original stories and episodes directly adapted from Arthur Conan Doyle's stories.

None of the episodes in which Rathbone and Bruce starred on the radio program were filmed with the two actors as Holmes and Watson, so radio became the only medium in which audiences were able to experience Rathbone and Bruce appearing in some of the more famous Holmes stories, such as "The Speckled Band". There were also many dramatizations of Sherlock Holmes stories on radio without Rathbone and Bruce.

During the latter part of his career, celebrated actor John Barrymore starred in a radio program, Streamlined Shakespeare, which featured him in a series of one-hour adaptations of Shakespeare plays, many of which Barrymore never appeared in either on stage or in films, such as Twelfth Night (in which he played both Malvolio and Sir Toby Belch), and Macbeth.

Lux Radio Theatre and The Screen Guild Theater presented adaptations of Hollywood movies, performed before a live audience, usually with cast members from the original films. Suspense, Escape, The Mysterious Traveler and Inner Sanctum Mystery were popular thriller anthology series.

Leading writers who created original material for radio included:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Golden Age of Radio:

It began with the birth of commercial radio broadcasting in the early 1920s and lasted until the 1950s, when television superseded radio as the medium of choice for scripted programming. The last few scripted radio dramas and full-service radio stations ended in 1962.

During this period radio was the only broadcast medium, and people regularly tuned into their favorite radio programs, and families gathered to listen to the home radio in the evening. According to a 1947 C. E. Hooper survey, 82 out of 100 Americans were found to be radio listeners.

A variety of new entertainment formats and genres were created for the new medium, many of which later migrated to television: radio plays, mystery serials, soap operas, quiz shows, talent shows, variety hours, situation comedies, play-by-play sports, children's shows, cooking shows.

Since this era, radio programming has shifted to a more narrow format of news, talk, sports and music.

Origins:

The broadcasts of live drama, comedy, music and news that characterize the Golden Age of Radio had a precedent in the Théâtrophone, commercially introduced in Paris in 1890 and available as late as 1932. It allowed subscribers to eavesdrop on live stage performances and hear news reports by means of a network of telephone lines. The development of radio eliminated the wires and subscription charges from this concept.

Boy learning how to build his own radio circa 1922.On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden is said to have broadcast the first radio program, consisting of some violin playing and passages from the Bible. While Fessenden's role as an inventor and early radio experimenter is not in dispute, several contemporary radio researchers have questioned whether the Christmas Eve broadcast took place, or whether the date was in fact several weeks earlier.

The first apparent published reference to the event was made in 1928 by H.P. Davis, Vice President of Westinghouse, in a lecture given at Harvard University. In 1932 Fessenden cited the Christmas Eve 1906 broadcast event in a letter he wrote to Vice President S.M. Kinter of Westinghouse. Fessenden's wife Helen recounts the broadcast in her book Fessenden: Builder of Tomorrows (1940), eight years after Fessenden's death.

The issue of whether the 1906 Fessenden broadcast actually happened is discussed in Donna Halper's article "In Search of the Truth About Fessenden" and also in James O'Neal's essays. An annotated argument supporting Fessenden as the world's first radio broadcaster was offered in 2006 by Dr. John S. Belrose, Radioscientist Emeritus at the Communications Research Centre Canada, in his essay "Fessenden's 1906 Christmas Eve broadcast."

It was not until after the Titanic catastrophe in 1912 that radio for mass communication came into vogue, inspired first by the work of amateur ("ham") radio operators. Radio was especially important during World War I as it was vital for air and naval operations.

World War I brought about major developments in radio, superseding the Morse code of the wireless telegraph with the vocal communication of the wireless telephone, through advancements in vacuum tube technology and the introduction of the transceiver.

After the war, numerous radio stations were born in the United States and set the standard for later radio programs. The first radio news program was broadcast on August 31, 1920 on the station 8MK in Detroit; owned by The Detroit News, the station covered local election results.

This was followed in 1920 with the first commercial radio station in the United States, KDKA, being established in Pittsburgh. The first regular entertainment programs were broadcast in 1922, and on March 10, Variety carried the front-page headline: "Radio Sweeping Country: 1,000,000 Sets in Use." A highlight of this time was the first Rose Bowl being broadcast on January 1, 1923 on the Los Angeles station KHJ.

Radio networks:

Several radio networks broadcast in the United States, airing programs nationwide. Their distribution made the golden age of radio possible. The networks declined in the early 1960s; Mutual and NBC both closed down their radio operations in the 1990s, while ABC lasted until 2007 when it was bought by Citadel Broadcasting, which was in turn merged with Cumulus Media on September 16, 2011.

As of November 14, 2013, Mutual, ABC and NBC's radio assets now reside with Cumulus Media's Westwood One division through numerous mergers and acquisitions since the mid-1980s. CBS still operates its network as of 2016, which is expected to close down mid 2017 as its radio assets are in the process of being integrated with Entercom as of February 2, 2017.

The major networks were:

- National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Red Network a development by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), 1926

- NBC Blue Network, launched 1927, divested under antitrust law and became the American Broadcasting Company in 1945

- Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), 1927

- Mutual Broadcasting System, 1934. Mutual was initially run as a cooperative in which the flagship stations owned the network, not the other way around as was the case with the Big Three.

Types of programs:

During the Golden Age of Radio, new forms of entertainment were created for the new medium, which later migrated to television and other media, including:

- radio plays, mystery, adventure and detective serials,

- soap operas,

- quiz shows,

- variety hours,

- talent shows,

- situation comedies,

- children's shows,

- as well as live musical concerts

- and play by play sports broadcasts.

In addition, the capability of the new medium to get information to people created the format of modern radio news: headlines, remote reporting, sidewalk interviews (such as Vox Pop), panel discussions, weather reports, farm reports.

The earliest radio programs of the 1920s were largely unsponsored; radio stations were a service designed to sell radio receivers. By the late 1920s, radio had reached critical mass and saturated the market, necessitating a change in business model. The sponsored musical feature soon became most popular program format.

Most early radio sponsorship came in the form of selling the naming rights to the program, as evidenced by such programs as The A&P Gypsies, Champion Spark Plug Hour, The Clicquot Club Eskimos, and King Biscuit Time. Commercials as they are known in the modern era were still relatively uncommon and considered intrusive.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the leading orchestras were heard often through big band remotes, and NBC's Monitor continued such remotes well into the 1950s by broadcasting live music from New York City jazz clubs to rural America.

Classical music programs on the air included The Voice of Firestone and The Bell Telephone Hour. Texaco sponsored the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts; the broadcasts, now sponsored by the Toll Brothers, continue to this day around the world, and are one of the few examples of live classical music still broadcast on radio.

One of the most notable of all classical music radio programs of the Golden Age of Radio featured the celebrated Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which had been created especially for him. At that time, nearly all classical musicians and critics considered Toscanini the greatest living maestro. Popular songwriters such as George Gershwin were also featured on radio. (Gershwin, in addition to frequent appearances as a guest, also had his own program in 1934.) The New York Philharmonic also had weekly concerts on radio.

There was no dedicated classical music radio station like NPR at that time, so classical music programs had to share the network they were broadcast on with more popular ones, much as in the days of television before the creation of NET and PBS.

Country music also enjoyed popularity. National Barn Dance, begun on Chicago's WLS in 1924, was picked up by NBC Radio in 1933. In 1925, WSM Barn Dance went on the air from Nashville. It was renamed the Grand Ole Opry in 1927 and NBC carried portions from 1944 to 1956. NBC also aired The Red Foley Show from 1951 to 1961, and ABC Radio carried Ozark Jubilee from 1953 to 1961.

Radio attracted top comedy talents from vaudeville and Hollywood for many years, including:

- Abbott and Costello,

- Fred Allen,

- Jack Benny,

- Victor Borge,

- Fanny Brice,

- Billie Burke,

- Bob Burns,

- Judy Canova,

- Eddie Cantor,

- Jimmy Durante,

- Phil Harris,

- Bob Hope,

- Groucho Marx,

- Jean Shepherd,

- Red Skelton,

- and Ed Wynn.

Situational comedies also gained popularity, including:

- Amos 'n' Andy,

- Burns and Allen,

- Easy Aces,

- Ethel and Albert,

- Fibber McGee and Molly,

- The Goldbergs,

- The Great Gildersleeve,

- The Halls of Ivy (which featured screen star Ronald Colman and his wife Benita Hume),

- Meet Corliss Archer,

- Meet Millie,

- and Our Miss Brooks.

Radio comedy ran the gamut from the small town humor of Lum and Abner, Herb Shriner and Minnie Pearl to the dialect characterizations of Mel Blanc and the caustic sarcasm of Henry Morgan.

Gags galore were delivered weekly on Stop Me If You've Heard This One and Can You Top This?, panel programs devoted to the art of telling jokes.

Quiz shows were lampooned on It Pays to Be Ignorant, and other memorable parodies were presented by such satirists as Spike Jones, Stoopnagle and Budd, Stan Freberg and Bob and Ray. British comedy reached American shores in a major assault when NBC carried The Goon Show in the mid-1950s.

Some shows originated as stage productions: Clifford Goldsmith's play What a Life was reworked into NBC's popular, long-running The Aldrich Family (1939–1953) with the familiar catchphrases "Henry! Henry Aldrich!," followed by Henry's answer, "Coming, Mother!"

Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway hit, You Can't Take It with You (1936), became a weekly situation comedy heard on Mutual (1944) with Everett Sloane and later on NBC (1951) with Walter Brennan.

Other shows were adapted from comic strips, including

- Blondie,

- Dick Tracy,

- Gasoline Alley,

- The Gumps,

- Li'l Abner,

- Little Orphan Annie,

- Popeye the Sailor,

- Red Ryder,

- Reg'lar Fellers,

- Terry and the Pirates

- and Tillie the Toiler.

Bob Montana's redheaded teen of comic strips and comic books was heard on radio's Archie Andrews from 1943 to 1953. The Timid Soul was a 1941–1942 comedy based on cartoonist H. T. Webster's famed Caspar Milquetoast character, and Robert L. Ripley's Believe It or Not! was adapted to several different radio formats during the 1930s and 1940s. Conversely, some radio shows gave rise to spinoff comic strips, such as My Friend Irma starring Marie Wilson.

The first soap opera, Clara, Lu, and Em was introduced in 1930 on Chicago's WGN. When daytime serials began in the early 1930s, they became known as soap operas because many were sponsored by soap products and detergents.

The line-up of late afternoon adventure serials included

- Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders,

- The Cisco Kid,

- Jack Armstrong,

- the All-American Boy,

- Captain Midnight,

- and The Tom Mix Ralston Straight Shooters.

Badges, rings, decoding devices and other radio premiums offered on these adventure shows were often allied with a sponsor's product, requiring the young listeners to mail in a boxtop from a breakfast cereal or other proof of purchase.

Radio dramas were presented on such programs as the following:

- 26 by Corwin,

- NBC Short Story,

- Arch Oboler's Plays,

- Quiet, Please,

- and CBS Radio Workshop.

Orson Welles's The Mercury Theatre on the Air and The Campbell Playhouse were considered by many critics to be the finest radio drama anthologies ever presented. They usually starred Welles in the leading role, along with celebrity guest stars such as Margaret Sullavan or Helen Hayes, in adaptations from literature, Broadway, and/or films.

They included such titles as Liliom, Oliver Twist (a title now feared lost), A Tale of Two Cities, Lost Horizon, and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. It was on Mercury Theatre that Welles presented his celebrated-but-infamous 1938 adaptation of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds, formatted to sound like a breaking news program.

Theatre Guild on the Air presented adaptations of classical and Broadway plays. Their Shakespeare adaptations included a one-hour Macbeth starring Maurice Evans and Judith Anderson, and a 90-minute Hamlet, starring John Gielgud. Recordings of many of these programs survive.

During the 1940s, Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, famous for playing Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in films, repeated their characterizations on radio on The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which featured both original stories and episodes directly adapted from Arthur Conan Doyle's stories.

None of the episodes in which Rathbone and Bruce starred on the radio program were filmed with the two actors as Holmes and Watson, so radio became the only medium in which audiences were able to experience Rathbone and Bruce appearing in some of the more famous Holmes stories, such as "The Speckled Band". There were also many dramatizations of Sherlock Holmes stories on radio without Rathbone and Bruce.

During the latter part of his career, celebrated actor John Barrymore starred in a radio program, Streamlined Shakespeare, which featured him in a series of one-hour adaptations of Shakespeare plays, many of which Barrymore never appeared in either on stage or in films, such as Twelfth Night (in which he played both Malvolio and Sir Toby Belch), and Macbeth.

Lux Radio Theatre and The Screen Guild Theater presented adaptations of Hollywood movies, performed before a live audience, usually with cast members from the original films. Suspense, Escape, The Mysterious Traveler and Inner Sanctum Mystery were popular thriller anthology series.

Leading writers who created original material for radio included:

- Norman Corwin,

- Carlton E. Morse,

- David Goodis,

- Archibald MacLeish,

- Arthur Miller,

- Arch Oboler,

- Wyllis Cooper,

- Rod Serling,

- Jay Bennett,

- and Irwin Shaw.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The Golden Age of Radio:

- Broadcast production methods

- History of professional radio recordings in the United States

- Recording media

- Availability of recordings

- Copyright status

- Legacy

- Museums

- See also:

- List of old-time radio programs

- List of old-time American radio people

- List of U.S. radio programs

- List of radio soap operas

- Antique radio

- Audio theater

- Carl Amari

- Classic Radio Theatre

- Hollywood 360

- The WGN Radio Theatre

- Chuck Schaden

- Music radio

- Radio comedy

- Radio drama

- Soap opera

- When Radio Was

- Radio Days (Woody Allen film dramatizing old-time radio)

- Remember WENN (AMC television series set at an old-time radio station in Pittsburgh)

- Gunsmoke series on WRCW Radio

- Old Time Radio on-line archive at Archive.org

- Old Time Radio on Way Back When

FM Radio Broadcasting

YouTube Video: How a Radio Station Works

Pictured: FM Broadcasting Studio

FM Radio broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting using frequency modulation (FM) technology.

Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, it is used worldwide to provide high-fidelity sound over broadcast radio.

FM broadcasting is capable of better sound quality than AM broadcasting, the chief competing radio broadcasting technology, so it is used for most music broadcasts. FM radio stations use the VHF frequencies.

The term "FM band" describes the frequency band in a given country which is dedicated to FM broadcasting.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about FM Radio Broadcasting:

Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, it is used worldwide to provide high-fidelity sound over broadcast radio.

FM broadcasting is capable of better sound quality than AM broadcasting, the chief competing radio broadcasting technology, so it is used for most music broadcasts. FM radio stations use the VHF frequencies.

The term "FM band" describes the frequency band in a given country which is dedicated to FM broadcasting.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about FM Radio Broadcasting:

- Broadcast bands

- Modulation characteristics

- Reception distance

- Adoption of FM broadcasting in the United States

- FM broadcasting switch-off

- Small-scale use of the FM broadcast band

- See also:

- FM broadcasting by country

- FM broadcasting (technical)

- Lists

- History

- U.S. Patent 1,941,066

- U.S. Patent 3,708,623 Compatible Four Channel FM System

- Introduction to FM MPX

- Stereo Multiplexing for Dummies Graphs that show waveforms at different points in the FM Multiplex process

- Factbook list of stations worldwide

- Invention History – The Father of FM

- Audio Engineering Society

- FM Broadcast and TV Broadcast Aural Subcarriers - Clifton Laboratories

AM Radio Broadcasting

YouTube Video of the First Radio Broadcast (1906)

YouTube Video of Jack Benny radio show 5/23/43 Parachute Jump

Pictured: “650 WSM AM Broadcasting from the Ryman.” (Nashville, TN)

AM broadcasting is a radio broadcasting technology, which employs amplitude modulation (AM) transmissions. It was the first method developed for making audio radio transmissions, and is still used worldwide, primarily for medium wave (also known as "AM band") transmissions, but also on the longwave and shortwave radio bands.

The earliest experimental AM transmissions were begun in the early 1900s. However, widespread AM broadcasting was not established until the 1920s, following the development of vacuum tube receivers and transmitters.

AM radio remained the dominant method of broadcasting for the next 30 years, a period called the "Golden Age of Radio", until television broadcasting became widespread in the 1950s and received most of the programming previously carried by radio.

Subsequently, AM radio's audiences have also greatly shrunk due to competition from FM (frequency modulation) radio, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), satellite radio, HD (digital) radio and Internet streaming.

AM transmissions are much more susceptible to interference than FM and digital signals, and often have limited audio fidelity. Thus, AM broadcasters tend to specialise in spoken-word formats, such as talk radio, all news and sports, leaving the broadcasting of music mainly to FM and digital stations.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about AM Broadcasting:

The earliest experimental AM transmissions were begun in the early 1900s. However, widespread AM broadcasting was not established until the 1920s, following the development of vacuum tube receivers and transmitters.

AM radio remained the dominant method of broadcasting for the next 30 years, a period called the "Golden Age of Radio", until television broadcasting became widespread in the 1950s and received most of the programming previously carried by radio.

Subsequently, AM radio's audiences have also greatly shrunk due to competition from FM (frequency modulation) radio, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), satellite radio, HD (digital) radio and Internet streaming.

AM transmissions are much more susceptible to interference than FM and digital signals, and often have limited audio fidelity. Thus, AM broadcasters tend to specialise in spoken-word formats, such as talk radio, all news and sports, leaving the broadcasting of music mainly to FM and digital stations.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about AM Broadcasting:

- History

- Technical information

- See also:

- Amplitude modulation

- Amplitude Modulation Signalling System, a digital system for adding low bitrate information to an AM broadcast signal.

- MW DXing, the hobby of receiving distant AM radio stations on the mediumwave band.

- History of radio

- Extended AM broadcast band

- CAM-D, a hybrid digital radio format for AM broadcasting

- List of 50 kW AM radio stations in the United States

- Lists of radio stations in North America

- Oldest radio station

Radio Formats, including a List of Formats

YouTube Video: Welcome to the KSHE 95 Real Rock Museum

A radio format or programming format (not to be confused with broadcast programming) describes the overall content broadcast on a radio station.

In countries where radio spectrum use is legally regulated (such as by OFCOM in the UK), formats may have a legal status where stations are licensed to transmit only specific formats.

Radio formats are frequently employed as a marketing tool, and are subject to frequent change. Music radio, old time radio, all-news radio, sports radio, talk radio and weather radio describe the operation of different genres of radio format and each format can often be sub-divided into many specialty formats.

List of formats:

Formats constantly evolve and each format can often be sub-divided into many specialty formats. Some of the following formats are available only regionally or through specialized venues such as satellite radio or Internet radio.

Music-oriented formats:

Pop/Adult Contemporary:

Rock/Alternative/Indie:

Country:

Urban/Rhythmic:

Dance/Electronic:

Jazz/Blues/Standards:

Easy Listening/New Age:

Folk/Singer-Songwriters:

Latin:

International:

Christian/Gospel:

Classical:

Seasonal/Holiday/Happening:

Miscellaneous:

Spoken word formats:

In countries where radio spectrum use is legally regulated (such as by OFCOM in the UK), formats may have a legal status where stations are licensed to transmit only specific formats.

Radio formats are frequently employed as a marketing tool, and are subject to frequent change. Music radio, old time radio, all-news radio, sports radio, talk radio and weather radio describe the operation of different genres of radio format and each format can often be sub-divided into many specialty formats.

List of formats:

Formats constantly evolve and each format can often be sub-divided into many specialty formats. Some of the following formats are available only regionally or through specialized venues such as satellite radio or Internet radio.

Music-oriented formats:

Pop/Adult Contemporary:

- Contemporary hit radio (CHR), occasionally still informally known as top-40 / hot hits)

- Adult contemporary music (AC)

- Adult/variety hits - Broad variety of pop hits spanning multiple eras and formats; Jack FM, Bob FM.

- Classic hits – 1970s/1980s-centered (previously 1960s-1970s) pop music

- Hot adult contemporary (Hot AC)

- Lite adult contemporary (Lite AC)

- Modern adult contemporary (Modern AC)

- Oldies – Late 1950s to early 1970s pop music

- Soft adult contemporary (soft AC)

Rock/Alternative/Indie:

- Active rock

- Adult album alternative (or just adult alternative) (AAA or Triple-A)

- Album rock / album-oriented rock (AOR)

- Alternative rock

- Classic alternative

- Classic rock

- Mainstream rock

- Modern rock

- Progressive rock

- Psychedelic rock

- Rock

- Soft rock

Country:

- Americana

- Bluegrass

- Country music:

- Classic country (exclusively older music)

- New country/Young country/Hot country (top 40 country with some non-country pop and no older music)

- Mainstream country (top 40 country with some older music)

- Traditional country (mix of old and new music)

Urban/Rhythmic:

- Classic hip-hop

- Quiet storm (most often a "daypart" late night format at urban and urban AC stations, i.e. 7 p.m.-12 a.m. midnight)

- Rhythmic adult contemporary

- Rhythmic contemporary (Rhythmic Top 40)

- Rhythmic oldies

- Urban:

- Urban contemporary (mostly rap, hip hop, soul, and contemporary R&B artists)

- Urban adult contemporary (Urban AC) – R&B (both newer and older), soul and sometimes gospel music, without hip hop and rap

- Urban oldies (sometimes called "classic soul", "R&B oldies", or "old school")

- Soul music

Dance/Electronic:

- Dance (dance top-40)

- Space music

Jazz/Blues/Standards:

Easy Listening/New Age:

- Adult standards / nostalgia (pre-rock)

- Beautiful music

- Easy Listening

- Middle of the road (MOR)

Folk/Singer-Songwriters:

- Folk music

Latin:

- Hispanic rhythmic

- Ranchera

- Regional Mexican (Banda, corridos, ranchera, conjunto, mariachi, norteño, etc.)

- Rock en español

- Romántica (Spanish AC)

- Spanish sub-formats:

- Tejano music (Texas/Mexican music)

- Also see: Ranchera, Regional Mexican, Romántica, and Tropical

- Tropical (salsa, merengue, cumbia, etc.)

International:

- Caribbean (reggae, soca, merengue, cumbia, salsa, etc.)

- Indian music

- Polka

- World music

Christian/Gospel:

- Christian music:

- Christian rock

- Contemporary Christian (which is also known as CCM)

- Urban Gospel

Classical:

Seasonal/Holiday/Happening:

- Christmas music (usually seasonal, mainly December)

Miscellaneous:

- Eclectic

- Freeform radio (DJ-selected)

Spoken word formats:

- All-news radio

- Children's

- Christian radio

- College radio

- Comedy radio

- Educational

- Ethnic/International

- Experimental

- Full-service (talk and variety music)

- Old time radio

- Radio audiobooks

- Radio documentary

- Radio drama

- Sports (Sports talk)

- News/Talk

- Weather radio

- See Also:

List of Radio Stations in the United States by Format

YouTube Video: Best Kept Secret in Radio | Lulu Miller | TEDxCharlottesville

Pictured: Station Logos by Format -- Clockwise from Upper Left: Country Music, Hip Hop Music, News/Sports/Talk, and St. Louis Cardinals Radio Network

Below, you will find an alphabetical List of Radio Stations in the United States by Format:

A

A

- ► Adult album alternative radio stations in the United States (121 P)

- ► Adult contemporary radio stations in the United States (2 C, 448 P)

- ► Adult hits radio stations in the United States (3 C, 111 P)

- ► Adult standards radio stations in the United States (137 P)

- ► All news radio stations in the United States (21 P)

- ► Children's radio stations in the United States (1 C, 9 P)

- ► Christian radio stations in the United States (13 C, 954 P)

- ► Christmas radio stations in the United States (7 P)

- ► Classic country radio stations in the United States (185 P)

- ► Classic hip-hop radio stations in the United States (21 P)

- ► Classic hits radio stations in the United States (1 C, 437 P)

- ► Classical music radio stations in the United States (2 C, 204 P)

- ► College radio stations in the United States (52 C, 2 P)

- ► Comedy radio stations in the United States (8 P)

- ► Community radio stations in the United States (2 C, 232 P)

- ► Contemporary Christian radio stations in the United States (291 P)

- ► Contemporary hit radio stations in the United States (2 C, 466 P)

- ► Country radio stations in the United States (3 C, 1,360 P)

- ► Gospel radio stations in the United States (1 C, 147 P)

- ► Hawaiian-music formatted radio stations (13 P)

- ► High school radio stations in the United States (93 P)

- ► Hot adult contemporary radio stations in the United States (2 C, 229 P)

- ► Jazz radio stations in the United States (2 C, 85 P)

- ► Oldies radio stations in the United States (1 C, 387 P)

- ► Public radio stations in the United States (9 C, 39 P)

- ► Radio reading services of the United States (15 P)

- ► Religious radio stations in the United States (2 C, 353 P)

- ► Rhythmic contemporary radio stations in the United States (1 C, 139 P)

- ► Rock radio stations in the United States (7 C, 2 P)

- ►List of urban-format radio stations in the United States

- ► Soft adult contemporary radio stations in the United States (27 P)

- ► Sports radio stations in the United States (8 C, 467 P)

- ► Talk radio stations in the United States (1 C, 185 P)

Radio Personalities including a List of Most-listened to Radio Personalities

YouTube Video of Howard Stern Interviews John Stamos

* -- Howard Stern Show

Pictured Clockwise from Upper Left: Steve Harvey Morning Show; NPR’s Morning Edition Host Steve Inskeep; Chris Thile (Prairie Home Companion) ; Don Imus

A radio personality (American English) or radio presenter (British English), commonly referred to as a "disc jockey" or "DJ" for short, is a person who has an on-air position in radio broadcasting.

A radio personality that hosts a radio show is also known as a radio host. Radio personalities who introduce and play individual selections of recorded music are known as disc jockeys. The term has evolved to also describe a person who mixes a continuous flow of recorded music in real time. Broadcast radio personalities may include talk radio hosts, AM/FM radio show hosts, and satellite radio program hosts.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Radio Personalities:

- Notable radio personalities

- Description

- History

- Types of radio personalities

- Salary in the US

- Career opportunities

- Training

- Education

- Job requirements

- See also:

List of the Most Popular Radio Personalities:

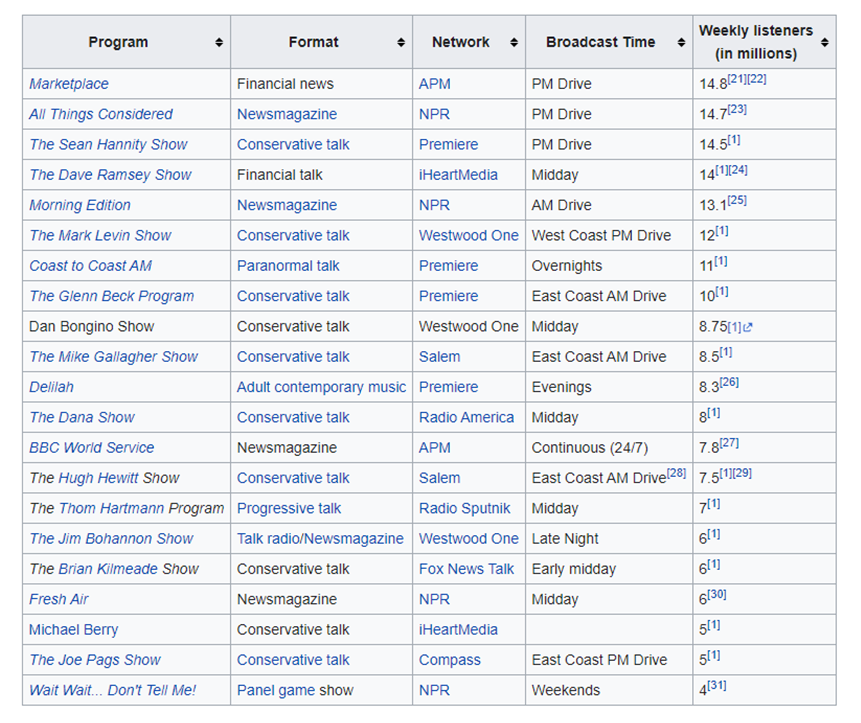

In the United States, the most popular radio listeners is gauged by Nielsen and others for both commercial radio and public radio. Nielsen and similar services provide estimates by regional market and by standard daypart, but does not compile nationwide information by host.

Because there are significant gaps in Nielsen's coverage in rural areas, and because there are only a few markets where the company's proprietary data can be compared against competing ratings measurers, there is a great deal of estimation and interpolation when attempting to compile a list of the most-listened-to radio programs in the United States. Nielsen itself admits the task of measuring individual shows would be too complicated and difficult for them to manage.

Talkers Magazine, an American trade publication focusing on talk radio, formerly compiled a list of the most-listened-to commercial long-form talk shows in the United States, based primarily on Nielsen data and estimated to the nearest 250,000 listeners. In addition to Talkers' independent analyses, radio companies of all formats include estimates of audience in news releases. The nature of news releases allows radio companies to inflate their listener totals by obscuring the difference between listeners at any given time, cumulative listenership over a time frame, and potential audience.

Popular radio shows in the United States:

The total listenership for terrestrial radio as of January 2017 was 256 million, up from 230 million in 2005:

- Sirius XM Radio has a base of 30.6 million subscribers as of 2016.

- American Top 40 attracts over 20 million listeners per week.

- Rush Limbaugh's show has been the number one commercial talk show since at least 1987 when record keeping began.

- NPR's Morning Edition and All Things Considered are the two most popular news programs.

- Tom Kent self-estimates his listenership at over 23 million weekly listeners over all of his network's programs, which span the classic hits, adult hits and hot adult contemporary formats.

Until the development of portable people meters, Arbitron (Nielsen's predecessor in the radio measurement business) did not have the capability to measure individual airings of a program the way Nielsen Ratings can for television, and as such, it only measures in three-month moving averages each month. Portable people meters are currently only available in the largest markets Arbitron serves. Thus, it is impossible under current survey techniques to determine the listenership of an individual event such as the Super Bowl.

For most of its existence, Talkers Magazine compiled Arbitron's data, along with other sources, to estimate the minimum weekly audiences of various commercial long-form talk radio shows; its list was updated monthly until the magazine unceremoniously dropped the feature in 2016, then resumed publication in 2017.

The 2017 reintroduction also incorporates off-air distribution methods (particularly those that are Internet-based) but not satellite radio, as Talkers could not access data for that medium; as a result, the estimates for most shows increased dramatically when compared to the 2015 methodology. NPR and APM compile Arbitron's data for its public radio shows and releases analysis through press releases.

Included is a list of the most-listened-to radio shows in the United States according to weekly cumulative listenership, followed by a selection of shows of various formats that are most-listened-to within their category. (Unless otherwise noted, the Talkers "non-scientific" estimate is the source.

Click here to view the List of Most Popular Radio Shows

[Web Host: The following first of three FM radio stations is the stations I have listened to over the years, depending. KSHE95 is my "companion" as I work on this project, probably averaging 5-8 hours a day. As for DJs, I have no favorites as they are all great! KSHE's musical format is very close to my own musical tastes. AND, frequently they will play a musical artist/group that reminds me to add them to the "Popular Musical Artists"web page! KSHE recently celebrated its 55th anniversary!]

KSHE 95, "Real Rock Radio"

YouTube Video: KSHE 95 Lauren "Lern" Elwell of KSHE'95

YouTube Video: Movin On Original Recording KSHE Classic Really Cool Stuff

Pictured: KSHE's Logo

Click here for "Real Rock Museum" Video.

Click here for Current Airstaff.

Click here for Real Rock News.

Click here for Concert Calendar.

Click here for KSHE Schtuff Store

KSHE95 is a mainstream rock radio station licensed to Crestwood, Missouri which serves the Greater St. Louis area. KSHE transmits on 94.7 MHz and currently uses the slogan "KSHE 95, Real Rock Radio".

The station's studios have been located in the Powerhouse building at St. Louis Union Station since the 1990s, while the transmitter is located in Shrewsbury. KSHE is owned by Emmis Communications and has been since 1984.

KSHE recently announced its first HD Radio subchannel, which will broadcast a 24-hour version of longtime personality John Ulett's "KSHE Klassics" show.

History:

After working as an engineer for 20 years with the Pulitzer stations, KSD and KSD-TV, Ed Ceries invested his life savings and his considerable engineering efforts in building his own FM station, which he called KSHE. He literally built some of the equipment himself, and on February 11, 1961, the station signed on from the basement of the Ceries' home in suburban Crestwood.

The station called itself "The Lady of FM," and had a classical music format. For a while, all the announcers were women. Most of the basement was used for the station operations, with the Associated Press Teletype installed next to the clothes washer. The record library room doubled as an administrative office where Mrs. Ceries also did her ironing. Listener loyalty was strong, and at times they would come to the station with copies of classical selections they thought were better than the ones being played on KSHE.

Unfortunately, advertisers were not convinced FM radio—particularly classical music on FM radio—had much of an audience. After the first year, the format was adjusted to contain about 90% middle-of-the-road music and 10% classical, with nine daily news broadcasts. In 1964, the station was sold to Century Broadcasting.

New general manager Howard Grafman was convinced by his friend Ron Elz to adopt a new format that Elz had heard on a trip to San Francisco on KMPX: album-oriented rock, with high latitude given to individual DJs as to what to play.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, KSHE was influential in the growth of many midwestern bands such as Styx, Cheap Trick, REO Speedwagon and Head East. KSHE had a wide and varied play list, which popularized such rock artists as Lake from Germany, Stingray from South Africa, and rising bands from Australia and New Zealand like Midnight Oil and Split Enz, as well as playing the classics from the more well-known rock legends. The very first song played on KSHE in 1967 was Jefferson Airplane's "White Rabbit".

KSHE sometimes played music nonstop for hours without station identification, which eventually was brought to the attention of the FCC and warnings from the agency to identify as required.

In late 1967, '68 and most of '69 they would play whole albums in the late afternoon and late at night any day of the week. Albums played in their entirety included such titles as The Firesign Theatre's Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Him, The Who's Tommy, Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band's Let's Make Up and Be Friendly, Arlo Guthrie's Alice's Restaurant, and Iron Butterfly's In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida, just to name a few.

KSHE would frequently play concept albums in their entirety, as well as entire album sides from favorites such as Rush. Sunday evenings were dedicated to playing seven albums from seven different artists on a show called the Seventh Day starting in the late 1970s, a program that continues to this day. The albums usually were played from 7:00 pm until after midnight. The Seventh Day concept was later used by other stations around the country.

It's rumored that on a Saturday in 1969, Bob Seger hitchhiked from Detroit to St. Louis to perform an hour-long concert which was simulcast on KSHE and the then-new UHF TV station KDNL, after which he hitchhiked back to Detroit.

Instead of the broadcast convention of reading news ripped from the Associated Press or United Press International wire machine ("rip and read"), early KSHE newscasts introduced news topics by preceding the story with rock music excerpts that had lyrics introducing or commenting on the topic.

KSHE created a virtual museum on its website as a way of celebrating its 40th birthday. It contains video clips, audio clips, pictures and memorabilia. The first inductees (2007) were Rush, Kiss, Ted Nugent, and REO Speedwagon.

In March 2010, KSHE held its annual March Bandness—the third-longest version of this contest in the US. Along with the typical classic rock, KSHE's format also includes standard modern rock.

KSHE also has various sub-genres for various times of day, such as: Hair Band Doran (DJ: Mike Doran) from 8pm-9pm weekdays (previously called '80s at 8 under the previous DJ, Katy Kruze) and Monday Night Metal with Tom "Real Rock" Terbrock on Tuesday nights from 9 pm to midnight (originally on Monday night at 10 pm with Radio/Radical Rich from the mid-'80s until 1987 when it was moved to Tuesday night, until it was canceled in the mid-'90s; returning with Terbrock in the summer of 2006). At 5 pm each weekday, KSHE plays "The Daily Dose", two Led Zeppelin songs presented with trivia about their creation or notable performances of the songs.

Mascot:

The station mascot is a sunglasses-and-headphones-wearing pig named "Sweetmeat," the likeness of which originally appeared on the cover of Blodwyn Pig's 1969 album 'Ahead Rings Out'.

The cover of Blodwyn Pig's 1969 debut album, "Ahead Rings Out," which inspired the Sweetmeat character.Like the pig pictured on the LP cover, Sweetmeat first appeared with a joint in his mouth. This "controversial" detail disappeared in the early '80s in favor of an updated, cartoon "rocker" pig. In recent years, the station has returned to using the original image, along with the original KSHE-95 text logo.

At top, the cartoon Sweetmeat used in the 1980s; at bottom, "vintage" Sweetmeat used as of June 2013.Sweetmeat also inspired the name of Austin, Texas Christian Punk/Thrash band One Bad Pig.

See Also:

Click here for Current Airstaff.

Click here for Real Rock News.

Click here for Concert Calendar.

Click here for KSHE Schtuff Store

KSHE95 is a mainstream rock radio station licensed to Crestwood, Missouri which serves the Greater St. Louis area. KSHE transmits on 94.7 MHz and currently uses the slogan "KSHE 95, Real Rock Radio".

The station's studios have been located in the Powerhouse building at St. Louis Union Station since the 1990s, while the transmitter is located in Shrewsbury. KSHE is owned by Emmis Communications and has been since 1984.

KSHE recently announced its first HD Radio subchannel, which will broadcast a 24-hour version of longtime personality John Ulett's "KSHE Klassics" show.

History:

After working as an engineer for 20 years with the Pulitzer stations, KSD and KSD-TV, Ed Ceries invested his life savings and his considerable engineering efforts in building his own FM station, which he called KSHE. He literally built some of the equipment himself, and on February 11, 1961, the station signed on from the basement of the Ceries' home in suburban Crestwood.

The station called itself "The Lady of FM," and had a classical music format. For a while, all the announcers were women. Most of the basement was used for the station operations, with the Associated Press Teletype installed next to the clothes washer. The record library room doubled as an administrative office where Mrs. Ceries also did her ironing. Listener loyalty was strong, and at times they would come to the station with copies of classical selections they thought were better than the ones being played on KSHE.

Unfortunately, advertisers were not convinced FM radio—particularly classical music on FM radio—had much of an audience. After the first year, the format was adjusted to contain about 90% middle-of-the-road music and 10% classical, with nine daily news broadcasts. In 1964, the station was sold to Century Broadcasting.

New general manager Howard Grafman was convinced by his friend Ron Elz to adopt a new format that Elz had heard on a trip to San Francisco on KMPX: album-oriented rock, with high latitude given to individual DJs as to what to play.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, KSHE was influential in the growth of many midwestern bands such as Styx, Cheap Trick, REO Speedwagon and Head East. KSHE had a wide and varied play list, which popularized such rock artists as Lake from Germany, Stingray from South Africa, and rising bands from Australia and New Zealand like Midnight Oil and Split Enz, as well as playing the classics from the more well-known rock legends. The very first song played on KSHE in 1967 was Jefferson Airplane's "White Rabbit".

KSHE sometimes played music nonstop for hours without station identification, which eventually was brought to the attention of the FCC and warnings from the agency to identify as required.

In late 1967, '68 and most of '69 they would play whole albums in the late afternoon and late at night any day of the week. Albums played in their entirety included such titles as The Firesign Theatre's Waiting for the Electrician or Someone Like Him, The Who's Tommy, Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band's Let's Make Up and Be Friendly, Arlo Guthrie's Alice's Restaurant, and Iron Butterfly's In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida, just to name a few.

KSHE would frequently play concept albums in their entirety, as well as entire album sides from favorites such as Rush. Sunday evenings were dedicated to playing seven albums from seven different artists on a show called the Seventh Day starting in the late 1970s, a program that continues to this day. The albums usually were played from 7:00 pm until after midnight. The Seventh Day concept was later used by other stations around the country.

It's rumored that on a Saturday in 1969, Bob Seger hitchhiked from Detroit to St. Louis to perform an hour-long concert which was simulcast on KSHE and the then-new UHF TV station KDNL, after which he hitchhiked back to Detroit.

Instead of the broadcast convention of reading news ripped from the Associated Press or United Press International wire machine ("rip and read"), early KSHE newscasts introduced news topics by preceding the story with rock music excerpts that had lyrics introducing or commenting on the topic.

KSHE created a virtual museum on its website as a way of celebrating its 40th birthday. It contains video clips, audio clips, pictures and memorabilia. The first inductees (2007) were Rush, Kiss, Ted Nugent, and REO Speedwagon.

In March 2010, KSHE held its annual March Bandness—the third-longest version of this contest in the US. Along with the typical classic rock, KSHE's format also includes standard modern rock.

KSHE also has various sub-genres for various times of day, such as: Hair Band Doran (DJ: Mike Doran) from 8pm-9pm weekdays (previously called '80s at 8 under the previous DJ, Katy Kruze) and Monday Night Metal with Tom "Real Rock" Terbrock on Tuesday nights from 9 pm to midnight (originally on Monday night at 10 pm with Radio/Radical Rich from the mid-'80s until 1987 when it was moved to Tuesday night, until it was canceled in the mid-'90s; returning with Terbrock in the summer of 2006). At 5 pm each weekday, KSHE plays "The Daily Dose", two Led Zeppelin songs presented with trivia about their creation or notable performances of the songs.

Mascot:

The station mascot is a sunglasses-and-headphones-wearing pig named "Sweetmeat," the likeness of which originally appeared on the cover of Blodwyn Pig's 1969 album 'Ahead Rings Out'.

The cover of Blodwyn Pig's 1969 debut album, "Ahead Rings Out," which inspired the Sweetmeat character.Like the pig pictured on the LP cover, Sweetmeat first appeared with a joint in his mouth. This "controversial" detail disappeared in the early '80s in favor of an updated, cartoon "rocker" pig. In recent years, the station has returned to using the original image, along with the original KSHE-95 text logo.

At top, the cartoon Sweetmeat used in the 1980s; at bottom, "vintage" Sweetmeat used as of June 2013.Sweetmeat also inspired the name of Austin, Texas Christian Punk/Thrash band One Bad Pig.

See Also:

American comedy radio programs

YouTube Video of Mel Blanc, "The Man of a 1000 Voices", on the David Letterman Show

Pictured: Amos & Andy and George Burns & Gracie Allen

Presented alphabetically, this category contains American radio programs mostly devoted to comedy, either routines performed by the host or guests or recorded comedy material presented by the host.

Radio Shock Jocks

YouTube Video of the Best of Howard Stern

YouTube Video: Mark and Brian - LIVE In LA

Pictured Below Shock Jocks (L) Howard Stern (R) Don Imus

A shock jock is a type of radio broadcaster or disc jockey who entertains listeners or attracts attention using humor and/or melodramatic exaggeration that some portion of the listening audience may find offensive.

The term is usually used pejoratively to describe provocative or irreverent broadcasters whose mannerisms, statements and actions are typically offensive to many members of the community. It is a popular term, generally not used within the radio industry.

A shock jock is considered to be the radio equivalent of the tabloid newspaper, for which entertaining readers is as important as, or more important than, providing factual information. Within the radio industry, a radio station that relies primarily on shock jocks for its programming is said to have a hot talk format.

The term has been used in two broad (but sometimes overlapping) contexts:

Background:

The idea of an entertainer who breaks taboos or who is deliberately offensive is not a new one. Despite the claims of decency activists, blue comedians have existed throughout history; notoriously offensive performers (George Carlin, Petronius, Benny Bell, Le Pétomane, Redd Foxx and Lenny Bruce for example).

African-American Ralph Waldo Petey Greene (1931–1984), who started broadcasting in 1966, has been called the original radio shock jock by some, although the term was not used until 1986, two years after Greene's death. Greene was an influence on Howard Stern, whose radio shows in the 1980s led to the first widespread use of the term "shock jock".

Shock jocks also tend to push the envelope of decency in their market, and may appear to show a lack of regard for communications regulations (e.g., FCC rules in the U.S.) regarding content.

But nearly all American broadcasters have strict policies against content that is likely to draw indecency forfeitures, and air personalities are often contractually obligated to avoid broadcasting such content. Indecency fines are, in fact, rarely issued by U.S. regulators—no broadcaster has been issued a forfeiture for indecent content since 2003, although several earlier cases are in appeals court.

Popular envelope-pushing subjects for shock jocks include sexual (especially kinky) and/or scatological (toilet humor) topics, or just unabashed innuendo. Shock jocks may have sex workers as guests.

Many shock jocks have been fired as a result of such punishments as regulatory fines, loss of advertisers, or simply social and political outrage. On the other hand, it is also not uncommon for such broadcasters to be quickly rehired by another station or network.

Shock jocks in the United States have been censored under additional pressure from the United States government since the introduction of the Broadcast Decency Enforcement Act of 2005, which increased the fines on radio stations for violating decency guidelines by nearly 20 times.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Shock Jocks:

The term is usually used pejoratively to describe provocative or irreverent broadcasters whose mannerisms, statements and actions are typically offensive to many members of the community. It is a popular term, generally not used within the radio industry.

A shock jock is considered to be the radio equivalent of the tabloid newspaper, for which entertaining readers is as important as, or more important than, providing factual information. Within the radio industry, a radio station that relies primarily on shock jocks for its programming is said to have a hot talk format.

The term has been used in two broad (but sometimes overlapping) contexts:

- The radio announcer who deliberately makes outrageous, controversial, or shocking statements, or does boundary-pushing stunts to improve ratings.

- The political radio announcer who has an emotional outburst in response to a controversial government policy decision.

Background:

The idea of an entertainer who breaks taboos or who is deliberately offensive is not a new one. Despite the claims of decency activists, blue comedians have existed throughout history; notoriously offensive performers (George Carlin, Petronius, Benny Bell, Le Pétomane, Redd Foxx and Lenny Bruce for example).

African-American Ralph Waldo Petey Greene (1931–1984), who started broadcasting in 1966, has been called the original radio shock jock by some, although the term was not used until 1986, two years after Greene's death. Greene was an influence on Howard Stern, whose radio shows in the 1980s led to the first widespread use of the term "shock jock".

Shock jocks also tend to push the envelope of decency in their market, and may appear to show a lack of regard for communications regulations (e.g., FCC rules in the U.S.) regarding content.

But nearly all American broadcasters have strict policies against content that is likely to draw indecency forfeitures, and air personalities are often contractually obligated to avoid broadcasting such content. Indecency fines are, in fact, rarely issued by U.S. regulators—no broadcaster has been issued a forfeiture for indecent content since 2003, although several earlier cases are in appeals court.

Popular envelope-pushing subjects for shock jocks include sexual (especially kinky) and/or scatological (toilet humor) topics, or just unabashed innuendo. Shock jocks may have sex workers as guests.

Many shock jocks have been fired as a result of such punishments as regulatory fines, loss of advertisers, or simply social and political outrage. On the other hand, it is also not uncommon for such broadcasters to be quickly rehired by another station or network.

Shock jocks in the United States have been censored under additional pressure from the United States government since the introduction of the Broadcast Decency Enforcement Act of 2005, which increased the fines on radio stations for violating decency guidelines by nearly 20 times.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Shock Jocks:

- Notable incidents in North America

- See also:

Howard Stern, "Shock Jock"

- YouTube Video: Seth Rogen’s Best Moments on the Stern Show

- YouTube Video: Stern Show Guests’ Most Dangerous On-Set Stories

- YouTube Video: Howard Stern Remembers Ray Liotta

Howard Allan Stern (born January 12, 1954) is an American radio and television personality, comedian, and author. He is best known for his radio show, The Howard Stern Show, which gained popularity when it was nationally syndicated on terrestrial radio from 1986 to 2005. He has broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio since 2006.

Stern landed his first radio jobs while at Boston University. From 1976 to 1982, he developed his on-air personality through morning positions at:

Stern worked afternoons at WFAN in New York City from 1982 until his firing in 1985. In 1985, he began a 20-year run at WXRK in New York City; his morning show entered syndication in 1986 and aired in 60 markets and attracted 20 million listeners at its peak. In recent years, Stern's photography has been featured in Hamptons and WHIRL magazines.

From 2012 to 2015, Stern served as a judge on America's Got Talent.

Stern has won numerous industry awards, including Billboard's Nationally Syndicated Air Personality of the Year eight consecutive times, and he is the first to have the number one morning show in New York City and Los Angeles simultaneously.

Stern became the most fined radio host when the Federal Communications Commission issued fines totaling $2.5 million to station owners for content it deemed indecent. Stern became one of the highest-paid radio figures after signing a five-year deal with Sirius in 2004 worth $500 million.

Stern has described himself as the "King of All Media" since 1992 for his successes outside radio. He hosted and produced numerous late-night television shows, pay-per-view events, and home videos. Two of his books, Private Parts (1993) and Miss America (1995), entered The New York Times Best Seller list at number one and sold over one million copies.

The former was made into a biographical comedy film in 1997 that had Stern and his radio show staff star as themselves. It topped the US box office in its opening week and grossed $41.2 million domestically. Stern performs on its soundtrack, which charted the Billboard 200 at number one and was certified platinum for one million copies sold.

Stern's third book, Howard Stern Comes Again, was released in 2019.

For more about Howard Stern, click here.

Stern landed his first radio jobs while at Boston University. From 1976 to 1982, he developed his on-air personality through morning positions at:

- WRNW in Briarcliff Manor, New York;

- WCCC in Hartford, Connecticut;

- WLLZ in Detroit, Michigan;

- and WWDC in Washington, D.C.

Stern worked afternoons at WFAN in New York City from 1982 until his firing in 1985. In 1985, he began a 20-year run at WXRK in New York City; his morning show entered syndication in 1986 and aired in 60 markets and attracted 20 million listeners at its peak. In recent years, Stern's photography has been featured in Hamptons and WHIRL magazines.

From 2012 to 2015, Stern served as a judge on America's Got Talent.

Stern has won numerous industry awards, including Billboard's Nationally Syndicated Air Personality of the Year eight consecutive times, and he is the first to have the number one morning show in New York City and Los Angeles simultaneously.

Stern became the most fined radio host when the Federal Communications Commission issued fines totaling $2.5 million to station owners for content it deemed indecent. Stern became one of the highest-paid radio figures after signing a five-year deal with Sirius in 2004 worth $500 million.

Stern has described himself as the "King of All Media" since 1992 for his successes outside radio. He hosted and produced numerous late-night television shows, pay-per-view events, and home videos. Two of his books, Private Parts (1993) and Miss America (1995), entered The New York Times Best Seller list at number one and sold over one million copies.

The former was made into a biographical comedy film in 1997 that had Stern and his radio show staff star as themselves. It topped the US box office in its opening week and grossed $41.2 million domestically. Stern performs on its soundtrack, which charted the Billboard 200 at number one and was certified platinum for one million copies sold.

Stern's third book, Howard Stern Comes Again, was released in 2019.

For more about Howard Stern, click here.

Sirius XM Radio

- YouTube Video of SIRIUS XM streaming satellite radio review

- YouTube Video: How to use features of the SiriusXM All Access package

- YouTube Video: Sirius XM Radio User Guide

Sirius XM Holdings Inc. is an American broadcasting company headquartered in Midtown Manhattan, New York City that provides satellite radio and online radio services operating in the United States. It was formed by the 2008 merger of Sirius Satellite Radio and XM Satellite Radio, merging them into SiriusXM Radio.

The company also has a 70% equity interest in Sirius XM Canada, an affiliate company that provides Sirius and XM service in Canada. On 21 May 2013, Sirius XM Holdings, Inc. was incorporated, and in January 2020, Sirius XM reorganized their corporate structure, which made Sirius XM Radio Inc. a direct, wholly owned subsidiary of Sirius XM Holdings, Inc.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the merger of XM Satellite Radio and Sirius Satellite Radio, Inc. on 29 July 2008, 17 months after the companies first proposed it. The merger created a company with 18.5 million subscribers, and the deal was valued at US$3.3 billion, not including debt.

The proposed merger was opposed by those who felt it would create a monopoly. Sirius and XM argued that a merger was the only way that satellite radio could survive.

In September 2018, the company agreed to purchase the streaming music service Pandora, and this transaction was completed on 1 February 2019. Since then, SiriusXM has grown to be the largest audio entertainment company in North America

As of 11 April 2021, Sirius XM had approximately 34.9 million subscribers.

Sirius XM Radio is a primary entry point for the Emergency Alert System.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Sirius XM Satellite Radio:

The company also has a 70% equity interest in Sirius XM Canada, an affiliate company that provides Sirius and XM service in Canada. On 21 May 2013, Sirius XM Holdings, Inc. was incorporated, and in January 2020, Sirius XM reorganized their corporate structure, which made Sirius XM Radio Inc. a direct, wholly owned subsidiary of Sirius XM Holdings, Inc.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the merger of XM Satellite Radio and Sirius Satellite Radio, Inc. on 29 July 2008, 17 months after the companies first proposed it. The merger created a company with 18.5 million subscribers, and the deal was valued at US$3.3 billion, not including debt.

The proposed merger was opposed by those who felt it would create a monopoly. Sirius and XM argued that a merger was the only way that satellite radio could survive.

In September 2018, the company agreed to purchase the streaming music service Pandora, and this transaction was completed on 1 February 2019. Since then, SiriusXM has grown to be the largest audio entertainment company in North America

As of 11 April 2021, Sirius XM had approximately 34.9 million subscribers.

Sirius XM Radio is a primary entry point for the Emergency Alert System.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Sirius XM Satellite Radio:

- Pre-merger

- Merger

- Post-merger

- Programming

- Canadian counterparts

- Technical

- Milestones

- See also

- Sirius Satellite Radio, former company

- XM Satellite Radio, former company

- 1worldspace, former company

- List of Sirius XM Radio channels

- Official website

- Business data for Sirius XM Holdings:

List of Most Listened-To Radio Programs

- YouTube Video: Obama Warns Trump Against Relying On Executive Power | Morning Edition | NPR

- YouTube Video from the David Ramsey Show: Are You Ready to Take Control of Your Money?

- YouTube Video: THE JACK BENNY SHOW COMEDY OLD TIME RADIO SHOWS

In the United States, radio listenership is gauged by Nielsen and others for both commercial radio and public radio. Nielsen and similar services provide estimates by regional market and by standard daypart, but do not compile nationwide information by host.

Because there are significant gaps in Nielsen's coverage in rural areas, and because there are only a few markets where the company's proprietary data can be compared against competing ratings tabulators, there is a great deal of estimation and interpolation when attempting to compile a list of the most-listened-to radio programs in the United States.

In 2009, Arbitron, the American radio industry's largest audience-measurement company at the time (since subsumed into its television counterpart Nielsen), said that "the job of determining number of listeners for (any particular program or host) is too complicated, expensive and difficult for them to bother with."

In contrast, because most UK radio broadcasts are distributed consistently and nationwide, the complications of measuring audiences that are present in American radio are not present for British radio.

Talkers Magazine, an American trade publication focusing on talk radio, formerly compiled a list of the most-listened-to commercial long-form talk shows in the United States, based primarily on Nielsen data.