Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

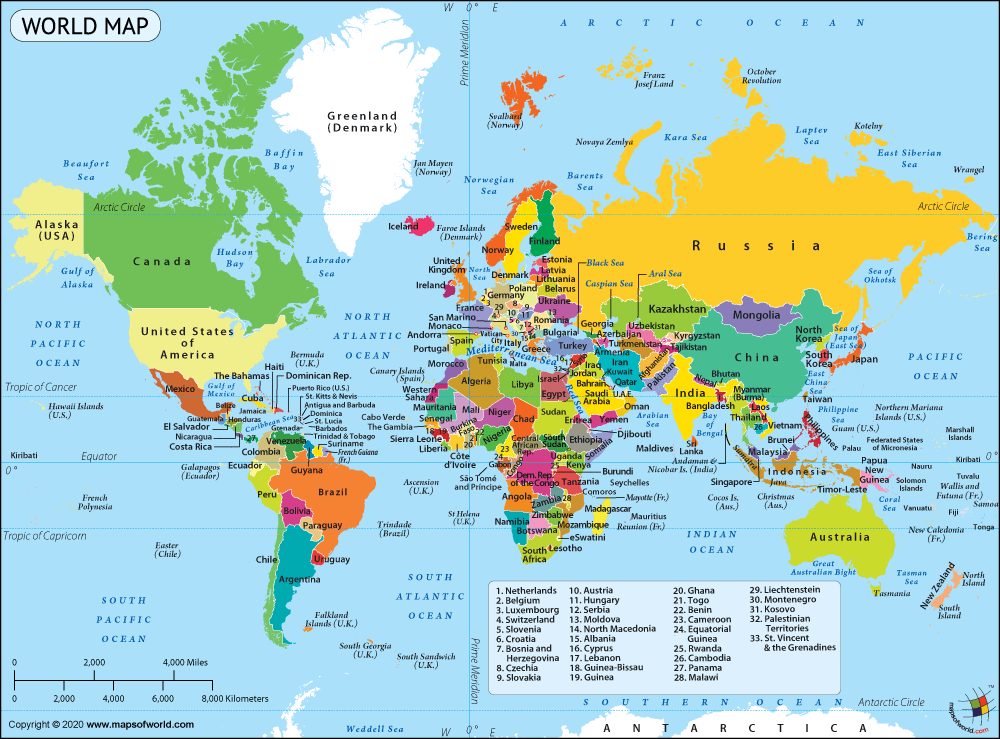

Nations

around the World, and including sovereign states along with various forms of rule (e.g., democracy, monarchy, theocracy, autocracy, etc.)

(Click on "Politics" to concerning how democracy works in the United States)

(Click on "Democracy in the United States" for Federal, State and Local Governments in the United States)

Nations around the World:

- YouTube Video: Cultures of the World | A fun overview of the world cultures for kids

- YouTube Video: THE BIRTH OF A NATION: Official HD Trailer

- YouTube Video: Matriarchal Societies Around the World | Infographics about Female Rulers

A nation is a large type of social organization where a collective identity has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as:

Some nations are constructed around ethnicity (see ethnic nationalism) while others are bound by political constitutions (see civic nationalism and multiculturalism).

A nation is generally more overtly political than an ethnic group. Benedict Anderson defines a nation as "an imagined political community […] imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”.

Anthony D Smith defines nations as cultural-political communities that have become conscious of their autonomy, unity and particular interests.

The consensus among scholars is that nations are socially constructed, historically contingent, and organizationally flexible. Throughout history, people have had an attachment to their kin group and traditions, territorial authorities and their homeland, but nationalism – the belief that state and nation should align as a nation state – did not become a prominent ideology until the end of the 18th century.

Etymology and terminology:

The English word nation came from the Latin natio, supine of verb nascar « to birth » (supine : natum), through French. In Latin, natio represents the children of the same birth and also a human group of same origin. By Cicero, natio is used for "people". Old French word nacion – meaning "birth" (naissance), "place of origin" –, which in turn originates from the Latin word natio (nātĭō) literally meaning "birth". Black's Law Dictionary defines a nation as follows:

nation, n. (14c)

1. A large group of people having a common origin, language, and tradition and usu. constituting a political entity. • When a nation is coincident with a state, the term nation-state is often used....

...

2. A community of people inhabiting a defined territory and organized under an independent government; a sovereign political state....

The word "nation" is sometimes used as synonym for:

Thus the phrase "nations of the world" could be referring to the top-level governments (as in the name for the United Nations), various large geographical territories, or various large ethnic groups of the planet.

Depending on the meaning of "nation" used, the term "nation state" could be used to distinguish larger states from small city states, or could be used to distinguish multinational states from those with a single ethnic group.

Medieval nations:

The existence of Medieval nations:

See also: Nationalism in the Middle Ages

Susan Reynolds has argued that many European medieval kingdoms were nations in the modern sense, except that political participation in nationalism was available only to a limited prosperous and literate class. On the other hand, Adrian Hastings claims England's Anglo-Saxon kings mobilized mass nationalism in their struggle to repel Norse invasions. He argues that Alfred the Great, in particular, drew on biblical language in his law code and that during his reign selected books of the Bible were translated into Old English to inspire Englishmen to fight to turn back the Norse invaders.

Hastings argues for a strong renewal of English nationalism (following a hiatus after the Norman conquest) beginning with the translation of the complete bible into English by the Wycliffe circle in the 1380s, positing that the frequency and consistency in usage of the word nation from the early fourteenth century onward strongly suggest English nationalism and the English nation have been continuous since that time.

However, John Breuilly criticizes the assumption that continued usage of a term such as 'English' means continuity in its meaning. Patrick J. Geary agrees, arguing names were adapted to different circumstances by different powers and could convince people of continuity, even if radical discontinuity was the lived reality.

Florin Curta cites Medieval Bulgarian nation as another possible example. Danubian Bulgaria was founded in 680-681 as a continuation of Great Bulgaria. After the adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 864 it became one of the cultural centres of Slavic Europe. Its leading cultural position was consolidated with the invention of the Cyrillic script in its capital Preslav on the eve of the 10th century.

Hugh Poulton argues the development of Old Church Slavonic literacy in the country had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighboring cultures and stimulated the development of a distinct ethnic identity. A symbiosis was carried out between the numerically weak Bulgars and the numerous Slavic tribes in that broad area from the Danube to the north, to the Aegean Sea to the south, and from the Adriatic Sea to the west, to the Black Sea to the east, who accepted the common ethnonym "Bulgarians".

During the 10th century the Bulgarians established a form of national identity that was far from modern nationalism but helped them to survive as a distinct entity through the centuries.

Anthony Kaldellis asserts in Hellenism in Byzantium (2008) that what is called the Byzantine Empire was the Roman Empire transformed into a nation-state in the Middle Ages.

Azar Gat also argues China, Korea and Japan were nations by the time of the European Middle Ages.

Criticisms:

In contrast, Geary rejects the conflation of early medieval and contemporary group identities as a myth, arguing it is a mistake to conclude continuity based on the recurrence of names.

He criticizes historians for failing to recognize the differences between earlier ways of perceiving group identities and more contemporary attitudes, stating they are "trapped in the very historical process we are attempting to study".

Similarly, Sami Zubaida notes that many states and empires in history ruled over ethnically diverse populations, and "shared ethnicity between ruler and ruled did not always constitute grounds for favour or mutual support". He goes on to argue ethnicity was never the primary basis of identification for the members of these multinational empires.

Use of term nationes by medieval universities and other medieval institutions:

Main article: Nation (university)

A significant early use of the term nation, as natio, occurred at Medieval universities to describe the colleagues in a college or students, above all at the University of Paris, who were all born within a pays, spoke the same language and expected to be ruled by their own familiar law.

In 1383 and 1384, while studying theology at Paris, Jean Gerson was elected twice as a procurator for the French natio. The University of Prague adopted the division of students into nationes: from its opening in 1349 the studium generale which consisted of Bohemian, Bavarian, Saxon and Polish nations.

In a similar way, the nationes were segregated by the Knights Hospitaller of Jerusalem, who maintained at Rhodes the hostels from which they took their name "where foreigners eat and have their places of meeting, each nation apart from the others, and a Knight has charge of each one of these hostels, and provides for the necessities of the inmates according to their religion", as the Spanish traveller Pedro Tafur noted in 1436.

Early modern nations:

See also: Nation state

In his article, "The Mosaic Moment: An Early Modernist Critique of the Modernist Theory of Nationalism", Philip S. Gorski argues that the first modern nation-state was the Dutch Republic, created by a fully modern political nationalism rooted in the model of biblical nationalism.

In a 2013 article "Biblical nationalism and the sixteenth-century states", Diana Muir Appelbaum expands Gorski's argument to apply to a series of new, Protestant, sixteenth-century nation states. A similar, albeit broader, argument was made by Anthony D. Smith in his books, Chosen Peoples: Sacred Sources of National Identity and Myths and Memories of the Nation.

In her book Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity, Liah Greenfeld argued that nationalism was invented in England by 1600. According to Greenfeld, England was “the first nation in the world".

Social science:

There are three notable perspectives on how nations developed:

Proponents of modernization theory describe nations as "imagined communities", a term coined by Benedict Anderson. A nation is an imagined community in the sense that the material conditions exist for imagining extended and shared connections and that it is objectively impersonal, even if each individual in the nation experiences themselves as subjectively part of an embodied unity with others.

For the most part, members of a nation remain strangers to each other and will likely never meet. Nationalism is consequently seen as an "invented tradition" in which shared sentiment provides a form of collective identity and binds individuals together in political solidarity.

A nation's foundational "story" may be built around a combination of ethnic attributes, values and principles, and may be closely connected to narratives of belonging.

Scholars in the 19th and early 20th century offered constructivist criticisms of primordial theories about nations. A prominent lecture by Ernest Renan, "What is a Nation?", argues that a nation is "a daily referendum", and that nations are based as much on what the people jointly forget as on what they remember.

Carl Darling Buck argued in a 1916 study, "Nationality is essentially subjective, an active sentiment of unity, within a fairly extensive group, a sentiment based upon real but diverse factors, political, geographical, physical, and social, any or all of which may be present in this or that case, but no one of which must be present in all cases."

In the late 20th century, many social scientists argued that there were two types of nations, the civic nation of which French republican society was the principal example and the ethnic nation exemplified by the German peoples.

The German tradition was conceptualized as originating with early 19th-century philosophers, like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and referred to people sharing a common language, religion, culture, history, and ethnic origins, that differentiate them from people of other nations.

On the other hand, the civic nation was traced to the French Revolution and ideas deriving from 18th-century French philosophers. It was understood as being centred in a willingness to "live together", this producing a nation that results from an act of affirmation. This is the vision, among others, of Ernest Renan.

Debate about a potential future of nations:

See also:

There is an ongoing debate about the future of nations − about whether this framework will persist as is and whether there are viable or developing alternatives

The theory of the clash of civilizations lies in direct contrast to cosmopolitan theories about an ever more-connected world that no longer requires nation states. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world.

The theory was originally formulated in a 1992 lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?", in response to Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy and capitalist free market economics had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world.

Specifically, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man, argued that the world had reached a Hegelian "end of history".

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had reverted only to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural and religious lines.

Postnationalism is the process or trend by which nation states and national identities lose their importance relative to supranational and global entities. Several factors contribute to its aspects including:

However attachment to citizenship and national identities often remains important.

Jan Zielonka of the University of Oxford states that "the future structure and exercise of political power will resemble the medieval model more than the Westphalian one" with the latter being about "concentration of power, sovereignty and clear-cut identity" and neo-medievalism meaning "overlapping authorities, divided sovereignty, multiple identities and governing institutions, and fuzzy borders".

See also:

Some nations are constructed around ethnicity (see ethnic nationalism) while others are bound by political constitutions (see civic nationalism and multiculturalism).

A nation is generally more overtly political than an ethnic group. Benedict Anderson defines a nation as "an imagined political community […] imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”.

Anthony D Smith defines nations as cultural-political communities that have become conscious of their autonomy, unity and particular interests.

The consensus among scholars is that nations are socially constructed, historically contingent, and organizationally flexible. Throughout history, people have had an attachment to their kin group and traditions, territorial authorities and their homeland, but nationalism – the belief that state and nation should align as a nation state – did not become a prominent ideology until the end of the 18th century.

Etymology and terminology:

The English word nation came from the Latin natio, supine of verb nascar « to birth » (supine : natum), through French. In Latin, natio represents the children of the same birth and also a human group of same origin. By Cicero, natio is used for "people". Old French word nacion – meaning "birth" (naissance), "place of origin" –, which in turn originates from the Latin word natio (nātĭō) literally meaning "birth". Black's Law Dictionary defines a nation as follows:

nation, n. (14c)

1. A large group of people having a common origin, language, and tradition and usu. constituting a political entity. • When a nation is coincident with a state, the term nation-state is often used....

...

2. A community of people inhabiting a defined territory and organized under an independent government; a sovereign political state....

The word "nation" is sometimes used as synonym for:

- State (polity) or sovereign state: a government that controls a specific territory, which may or may not be associated with any particular ethnic group

- Country: a geographic territory, which may or may not have an affiliation with a government or ethnic group

Thus the phrase "nations of the world" could be referring to the top-level governments (as in the name for the United Nations), various large geographical territories, or various large ethnic groups of the planet.

Depending on the meaning of "nation" used, the term "nation state" could be used to distinguish larger states from small city states, or could be used to distinguish multinational states from those with a single ethnic group.

Medieval nations:

The existence of Medieval nations:

See also: Nationalism in the Middle Ages

Susan Reynolds has argued that many European medieval kingdoms were nations in the modern sense, except that political participation in nationalism was available only to a limited prosperous and literate class. On the other hand, Adrian Hastings claims England's Anglo-Saxon kings mobilized mass nationalism in their struggle to repel Norse invasions. He argues that Alfred the Great, in particular, drew on biblical language in his law code and that during his reign selected books of the Bible were translated into Old English to inspire Englishmen to fight to turn back the Norse invaders.

Hastings argues for a strong renewal of English nationalism (following a hiatus after the Norman conquest) beginning with the translation of the complete bible into English by the Wycliffe circle in the 1380s, positing that the frequency and consistency in usage of the word nation from the early fourteenth century onward strongly suggest English nationalism and the English nation have been continuous since that time.

However, John Breuilly criticizes the assumption that continued usage of a term such as 'English' means continuity in its meaning. Patrick J. Geary agrees, arguing names were adapted to different circumstances by different powers and could convince people of continuity, even if radical discontinuity was the lived reality.

Florin Curta cites Medieval Bulgarian nation as another possible example. Danubian Bulgaria was founded in 680-681 as a continuation of Great Bulgaria. After the adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 864 it became one of the cultural centres of Slavic Europe. Its leading cultural position was consolidated with the invention of the Cyrillic script in its capital Preslav on the eve of the 10th century.

Hugh Poulton argues the development of Old Church Slavonic literacy in the country had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighboring cultures and stimulated the development of a distinct ethnic identity. A symbiosis was carried out between the numerically weak Bulgars and the numerous Slavic tribes in that broad area from the Danube to the north, to the Aegean Sea to the south, and from the Adriatic Sea to the west, to the Black Sea to the east, who accepted the common ethnonym "Bulgarians".

During the 10th century the Bulgarians established a form of national identity that was far from modern nationalism but helped them to survive as a distinct entity through the centuries.

Anthony Kaldellis asserts in Hellenism in Byzantium (2008) that what is called the Byzantine Empire was the Roman Empire transformed into a nation-state in the Middle Ages.

Azar Gat also argues China, Korea and Japan were nations by the time of the European Middle Ages.

Criticisms:

In contrast, Geary rejects the conflation of early medieval and contemporary group identities as a myth, arguing it is a mistake to conclude continuity based on the recurrence of names.

He criticizes historians for failing to recognize the differences between earlier ways of perceiving group identities and more contemporary attitudes, stating they are "trapped in the very historical process we are attempting to study".

Similarly, Sami Zubaida notes that many states and empires in history ruled over ethnically diverse populations, and "shared ethnicity between ruler and ruled did not always constitute grounds for favour or mutual support". He goes on to argue ethnicity was never the primary basis of identification for the members of these multinational empires.

Use of term nationes by medieval universities and other medieval institutions:

Main article: Nation (university)

A significant early use of the term nation, as natio, occurred at Medieval universities to describe the colleagues in a college or students, above all at the University of Paris, who were all born within a pays, spoke the same language and expected to be ruled by their own familiar law.

In 1383 and 1384, while studying theology at Paris, Jean Gerson was elected twice as a procurator for the French natio. The University of Prague adopted the division of students into nationes: from its opening in 1349 the studium generale which consisted of Bohemian, Bavarian, Saxon and Polish nations.

In a similar way, the nationes were segregated by the Knights Hospitaller of Jerusalem, who maintained at Rhodes the hostels from which they took their name "where foreigners eat and have their places of meeting, each nation apart from the others, and a Knight has charge of each one of these hostels, and provides for the necessities of the inmates according to their religion", as the Spanish traveller Pedro Tafur noted in 1436.

Early modern nations:

See also: Nation state

In his article, "The Mosaic Moment: An Early Modernist Critique of the Modernist Theory of Nationalism", Philip S. Gorski argues that the first modern nation-state was the Dutch Republic, created by a fully modern political nationalism rooted in the model of biblical nationalism.

In a 2013 article "Biblical nationalism and the sixteenth-century states", Diana Muir Appelbaum expands Gorski's argument to apply to a series of new, Protestant, sixteenth-century nation states. A similar, albeit broader, argument was made by Anthony D. Smith in his books, Chosen Peoples: Sacred Sources of National Identity and Myths and Memories of the Nation.

In her book Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity, Liah Greenfeld argued that nationalism was invented in England by 1600. According to Greenfeld, England was “the first nation in the world".

Social science:

There are three notable perspectives on how nations developed:

- Primordialism (perennialism), which reflects popular conceptions of nationalism but has largely fallen out of favour among academics, proposes that there have always been nations and that nationalism is a natural phenomenon.

- Ethnosymbolism explains nationalism as a dynamic, evolving phenomenon and stresses the importance of symbols, myths and traditions in the development of nations and nationalism.

- Modernization theory, which has superseded primordialism as the dominant explanation of nationalism, adopts a constructivist approach and proposes that nationalism emerged due to processes of modernization, such as industrialization, urbanization, and mass education, which made national consciousness possible.

Proponents of modernization theory describe nations as "imagined communities", a term coined by Benedict Anderson. A nation is an imagined community in the sense that the material conditions exist for imagining extended and shared connections and that it is objectively impersonal, even if each individual in the nation experiences themselves as subjectively part of an embodied unity with others.

For the most part, members of a nation remain strangers to each other and will likely never meet. Nationalism is consequently seen as an "invented tradition" in which shared sentiment provides a form of collective identity and binds individuals together in political solidarity.

A nation's foundational "story" may be built around a combination of ethnic attributes, values and principles, and may be closely connected to narratives of belonging.

Scholars in the 19th and early 20th century offered constructivist criticisms of primordial theories about nations. A prominent lecture by Ernest Renan, "What is a Nation?", argues that a nation is "a daily referendum", and that nations are based as much on what the people jointly forget as on what they remember.

Carl Darling Buck argued in a 1916 study, "Nationality is essentially subjective, an active sentiment of unity, within a fairly extensive group, a sentiment based upon real but diverse factors, political, geographical, physical, and social, any or all of which may be present in this or that case, but no one of which must be present in all cases."

In the late 20th century, many social scientists argued that there were two types of nations, the civic nation of which French republican society was the principal example and the ethnic nation exemplified by the German peoples.

The German tradition was conceptualized as originating with early 19th-century philosophers, like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and referred to people sharing a common language, religion, culture, history, and ethnic origins, that differentiate them from people of other nations.

On the other hand, the civic nation was traced to the French Revolution and ideas deriving from 18th-century French philosophers. It was understood as being centred in a willingness to "live together", this producing a nation that results from an act of affirmation. This is the vision, among others, of Ernest Renan.

Debate about a potential future of nations:

See also:

- Clash of Civilizations,

- City-state,

- Virtual community,

- Tribe (Internet),

- Global citizenship,

- Geographic mobility,

- Transnationalism,

- Geo-fence,

- Decentralization,

- Collective problem solving,

- and Sociocultural evolution

There is an ongoing debate about the future of nations − about whether this framework will persist as is and whether there are viable or developing alternatives

The theory of the clash of civilizations lies in direct contrast to cosmopolitan theories about an ever more-connected world that no longer requires nation states. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world.

The theory was originally formulated in a 1992 lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?", in response to Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy and capitalist free market economics had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world.

Specifically, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man, argued that the world had reached a Hegelian "end of history".

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had reverted only to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural and religious lines.

Postnationalism is the process or trend by which nation states and national identities lose their importance relative to supranational and global entities. Several factors contribute to its aspects including:

- economic globalization,

- a rise in importance of multinational corporations,

- the internationalization of financial markets,

- the transfer of socio-political power from national authorities to supranational entities, such as:

- multinational corporations,

- the United Nations and the European Union

- and the advent of new information and culture technologies such as the Internet.

However attachment to citizenship and national identities often remains important.

Jan Zielonka of the University of Oxford states that "the future structure and exercise of political power will resemble the medieval model more than the Westphalian one" with the latter being about "concentration of power, sovereignty and clear-cut identity" and neo-medievalism meaning "overlapping authorities, divided sovereignty, multiple identities and governing institutions, and fuzzy borders".

See also:

- Citizenship

- City network

- Country

- Government

- Identity (social science)

- Imagined Communities

- Invented tradition

- Lists of people by nationality

- Meta-ethnicity

- Multinational state

- National emblem

- National god

- National memory

- Nationalism

- Nationality

- People

- Polity

- Qaum

- Race (human categorization)

- Separatism

- Irredentism

- Society

- Sovereign state

- Stateless nation

- Tribe

- Republic

- Republicanism

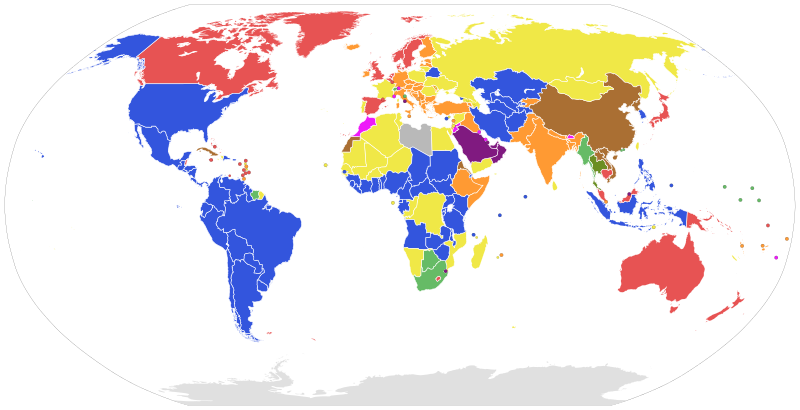

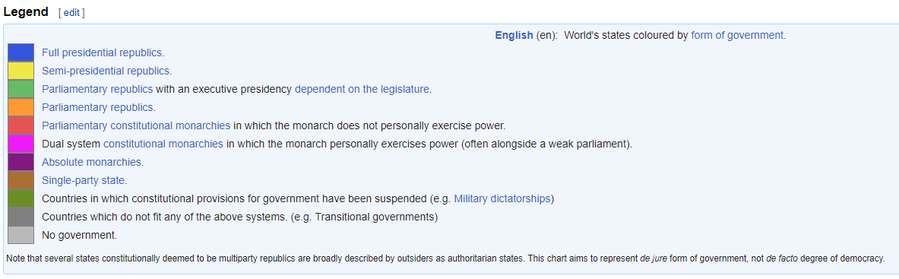

Sovereign States, including a List of Sovereign StatesPictured below: Systems of Governments

A sovereign state is a state with borders where people live, and where a government makes laws and talks to other sovereign states. The people have to follow the laws that the government makes. Most sovereign states are recognized which means other sovereign states agree that it's really a sovereign state. Being recognized makes it easier for a sovereign state to talk to and make agreements (treaties) with other sovereign states. There are hundreds of recognized sovereign states today.

There is no rule to say what exactly makes a state. Usually, the things a state must have are mainly political, not legal. The Czechs and the Poles were seen as separate states during World War I, even though they did not exist as states yet. L.C. Green explained this by saying that "recognition of statehood is a matter of discretion, it is open to any existing state to accept as a state any entity it wishes, regardless of the existence of territory or an established government."

This means that it is up to any state that already exists to treat any other group as a state. This recognition can be direct or implied. When a state does this, it usually means that the group will also be treated as a state for things that happened in the past. Sometimes it means that the state wants diplomatic relations with the other group, but not always.

Sovereignty is a word that is often used wrongly. Lassa Oppenheim said that there is no idea whose meaning is more controversial than sovereignty. No one argues the fact that from the time the idea of sovereignty was first used in political science until now, there has never been one meaning that everyone agreed on. Justice Evatt of the High Court of Australia says that "sovereignty is neither a question of fact, nor a question of law, but a question that does not arise at all."

Although the word sovereignty often includes all types of government, ancient and modern, the modern state has some links to the type of government first seen in the 15th century, when the term "state" also first meant what it does today. Because of this, the word is often used to refer only to modern political systems.

We often use the words "country", "nation", and "state" as if they mean the same thing; but there is actually a difference:

Because the meaning of the words has changed over time and past writers often used the word "state" in a different ways it is difficult to say exactly what a state is. Mikhail Bakunin used the word simply to mean a governing organization.

Other writers used the word "state" to mean any law-making or law enforcement agency. Karl Marx said that the state was what was used by the ruling class of a country to control the rule. According to Max Weber, the state is an organization who are the only people allowed to use violence in a particular area.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Sovereign States: ___________________________________________________________________________

This list of sovereign states provides an overview of sovereign states around the world, with information on their status and recognition of their sovereignty.

Membership within the United Nations system divides the 206 listed states into three categories: 193 member states, 2 observer states, and 11 other states. The sovereignty dispute column indicates states whose sovereignty is undisputed (191 states) and states whose sovereignty is disputed (15 states, out of which there are 5 member states, 1 observer state and 9 other states).

Compiling a list such as this can be a difficult and controversial process, as there is no definition that is binding on all the members of the community of nations concerning the criteria for statehood.

For more information on the criteria used to determine the contents of this list, please see the criteria for inclusion section below. The list is intended to include entities that have been recognized to have de facto status as sovereign states, and inclusion should not be seen as an endorsement of any specific claim to statehood in legal terms.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about a List of Sovereign States:

There is no rule to say what exactly makes a state. Usually, the things a state must have are mainly political, not legal. The Czechs and the Poles were seen as separate states during World War I, even though they did not exist as states yet. L.C. Green explained this by saying that "recognition of statehood is a matter of discretion, it is open to any existing state to accept as a state any entity it wishes, regardless of the existence of territory or an established government."

This means that it is up to any state that already exists to treat any other group as a state. This recognition can be direct or implied. When a state does this, it usually means that the group will also be treated as a state for things that happened in the past. Sometimes it means that the state wants diplomatic relations with the other group, but not always.

Sovereignty is a word that is often used wrongly. Lassa Oppenheim said that there is no idea whose meaning is more controversial than sovereignty. No one argues the fact that from the time the idea of sovereignty was first used in political science until now, there has never been one meaning that everyone agreed on. Justice Evatt of the High Court of Australia says that "sovereignty is neither a question of fact, nor a question of law, but a question that does not arise at all."

Although the word sovereignty often includes all types of government, ancient and modern, the modern state has some links to the type of government first seen in the 15th century, when the term "state" also first meant what it does today. Because of this, the word is often used to refer only to modern political systems.

We often use the words "country", "nation", and "state" as if they mean the same thing; but there is actually a difference:

- A nation is a group of people who are believed to share common customs, origins, and history. However, the adjectives national and international are used about what is strictly a sovereign state, as in national capital, international law.

- A state is the government and other supporting groups of people that have sovereignty over an area of land and population.

Because the meaning of the words has changed over time and past writers often used the word "state" in a different ways it is difficult to say exactly what a state is. Mikhail Bakunin used the word simply to mean a governing organization.

Other writers used the word "state" to mean any law-making or law enforcement agency. Karl Marx said that the state was what was used by the ruling class of a country to control the rule. According to Max Weber, the state is an organization who are the only people allowed to use violence in a particular area.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Sovereign States: ___________________________________________________________________________

This list of sovereign states provides an overview of sovereign states around the world, with information on their status and recognition of their sovereignty.

Membership within the United Nations system divides the 206 listed states into three categories: 193 member states, 2 observer states, and 11 other states. The sovereignty dispute column indicates states whose sovereignty is undisputed (191 states) and states whose sovereignty is disputed (15 states, out of which there are 5 member states, 1 observer state and 9 other states).

Compiling a list such as this can be a difficult and controversial process, as there is no definition that is binding on all the members of the community of nations concerning the criteria for statehood.

For more information on the criteria used to determine the contents of this list, please see the criteria for inclusion section below. The list is intended to include entities that have been recognized to have de facto status as sovereign states, and inclusion should not be seen as an endorsement of any specific claim to statehood in legal terms.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about a List of Sovereign States:

- List of states

- Criteria for inclusion

- See also:

- ISO 3166-1

- Adjectivals and demonyms for countries and nations

- Gallery of country coats of arms

- Gallery of sovereign state flags

- List of countries and capitals in native languages

- List of national capitals in alphabetical order

- List of country-name etymologies

- List of dependent territories

- List of international rankings

- List of micronations

- List of rebel groups that control territory

- List of states with limited recognition

- List of territorial disputes

- Sovereign state

- List of administrative divisions by country

- Template:Clickable world map

- Terra nullius

United Nations and the UN Security Council including a List of Member States, and UN's Specialized Agencies

- YouTube Video about The United Nations: "It's Your World"

- YouTube Video: LIVE: World leaders hold UN Security Council meeting on Ukraine

- YouTube Video: UN General Assembly holds an emergency special meeting on Israel and Gaza

Click here for a List of Member States of the United Nations.

Click here for List of specialized agencies of the United Nations.

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization tasked to promote international co-operation and to create and maintain international order. A replacement for the ineffective League of Nations, the organization was established on 24 October 1945 after World War II in order to prevent another such conflict.

At its founding, the UN had 51 member states; there are now 193. The headquarters of the UN is in Manhattan, New York City, and is subject to extraterritoriality. Further main offices are situated in Geneva, Nairobi, and Vienna.

The organization is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from its member states. Its objectives include maintaining international peace and security, promoting human rights, fostering social and economic development, protecting the environment, and providing humanitarian aid in cases of famine, natural disaster, and armed conflict. The UN is the largest, most familiar, most internationally represented and most powerful intergovernmental organization in the world.

The UN Charter was drafted at a conference between April–June 1945 in San Francisco, and was signed on 26 June 1945 at the conclusion of the conference; this charter took effect 24 October 1945, and the UN began operation. The UN's mission to preserve world peace was complicated in its early decades by the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union and their respective allies.

The organization participated in major actions in Korea and the Congo, as well as approving the creation of the state of Israel in 1947. The organization's membership grew significantly following widespread decolonization in the 1960s, and by the 1970s its budget for economic and social development programs far outstripped its spending on peacekeeping. After the end of the Cold War, the UN took on major military and peacekeeping missions across the world with varying degrees of success.

The UN has six principal organs:

UN System agencies include:

The UN's most prominent officer is the Secretary-General, an office held by Portuguese António Guterres since 2017.

Non-governmental organizations may be granted consultative status with ECOSOC and other agencies to participate in the UN's work.

The organization won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, and a number of its officers and agencies have also been awarded the prize.

Other evaluations of the UN's effectiveness have been mixed. Some commentators believe the organization to be an important force for peace and human development, while others have called the organization ineffective, corrupt, or biased.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United Nations:

United Nations Security Council:

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations, charged with the maintenance of international peace and security as well as accepting new members to the United Nations and approving any changes to its United Nations Charter.

Its powers include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of international sanctions, and the authorization of military action through Security Council resolutions; it is the only UN body with the authority to issue binding resolutions to member states.

The Security Council held its first session on 17 January 1946.

Like the UN as a whole, the Security Council was created following World War II to address the failings of a previous international organization, the League of Nations, in maintaining world peace.

In its early decades, the Security Council was largely paralyzed by the Cold War division between the US and USSR and their respective allies, though it authorized interventions in the Korean War and the Congo Crisis and peacekeeping missions in the Suez Crisis, Cyprus, and West New Guinea.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, UN peacekeeping efforts increased dramatically in scale, and the Security Council authorized major military and peacekeeping missions in Kuwait, Namibia, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Security Council consists of fifteen members. The great powers that were the victors of World War II—the Soviet Union (now represented by the Russian Federation), the United Kingdom, France, the Republic of China (now represented by the People's Republic of China), and the United States—serve as the body's five permanent members.

These permanent members can veto any substantive Security Council resolution, including those on the admission of new member states or candidates for Secretary-General.

The Security Council also has 10 non-permanent members, elected on a regional basis to serve two-year terms. The body's presidency rotates monthly among its members.

Security Council resolutions are typically enforced by UN peacekeepers, military forces voluntarily provided by member states and funded independently of the main UN budget.

As of 2016, 103,510 peacekeepers and 16,471 civilians were deployed on sixteen peacekeeping operations and one special political mission.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the NATO Security Council:

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; French: Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 78th session, its powers, composition, functions, and procedures are set out in Chapter IV of the United Nations Charter.

The UNGA is responsible for the UN budget, appointing the non-permanent members to the Security Council, appointing the UN secretary-general, receiving reports from other parts of the UN system, and making recommendations through resolutions. It also establishes numerous subsidiary organs to advance or assist in its broad mandate. The UNGA is the only UN organ where all member states have equal representation.

The General Assembly meets under its President or the UN secretary-general in annual sessions at the General Assembly Building, within the UN headquarters in New York City.

The main part of these meetings generally runs from September through part of January until all issues are addressed, which is often before the next session starts. It can also reconvene for special and emergency special sessions. The first session was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of the 51 founding nations.

Most questions are decided in the General Assembly by a simple majority. Each member country has one vote. Voting on certain important questions—namely recommendations on peace and security; budgetary concerns; and the election, admission, suspension, or expulsion of members—is by a two-thirds majority of those present and voting. Apart from the approval of budgetary matters, including the adoption of a scale of assessment, Assembly resolutions are not binding on the members.

The Assembly may make recommendations on any matters within the scope of the UN, except matters of peace and security under the Security Council's consideration.

During the 1980s, the Assembly became a forum for "North-South dialogue" between industrialized nations and developing countries on a range of international issues. These issues came to the fore because of the phenomenal growth and changing makeup of the UN membership. In 1945, the UN had 51 members, which by the 21st century nearly quadrupled to 193, of which more than two-thirds are developing countries.

Because of their numbers, developing countries are often able to determine the agenda of the Assembly (using coordinating groups like the G77), the character of its debates, and the nature of its decisions. For many developing countries, the UN is the source of much of their diplomatic influence and the principal outlet for their foreign relations initiatives.

Although the resolutions passed by the General Assembly do not have the binding forces over the member nations (apart from budgetary measures), pursuant to its Uniting for Peace resolution of November 1950 (resolution 377 (V)), the Assembly may also take action if the Security Council fails to act, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member, in a case where there appears to be a threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression.

The Assembly can consider the matter immediately with a view to making recommendations to Members for collective measures to maintain or restore international peace and security.

Membership:

Main article: Member states of the United Nations

All 193 members of the United Nations are members of the General Assembly, with the addition of the Holy See and Palestine as observer states as well as the European Union (since 1974). Further, the United Nations General Assembly may grant observer status to an international organization or entity, which entitles the entity to participate in the work of the United Nations General Assembly, though with limitations.

Agenda:

The agenda for each session is planned up to seven months in advance and begins with the release of a preliminary list of items to be included in the provisional agenda. This is refined into a provisional agenda 60 days before the opening of the session.

After the session begins, the final agenda is adopted in a plenary meeting which allocates the work to the various main committees, who later submit reports back to the Assembly for adoption by consensus or by vote.

Items on the agenda are numbered. Regular plenary sessions of the General Assembly in recent years have initially been scheduled to be held over the course of just three months; however, additional workloads have extended these sessions until just short of the next session.

The routinely scheduled portions of the sessions normally commence on "the Tuesday of the third week in September, counting from the first week that contains at least one working day", per the UN Rules of Procedure. The last two of these Regular sessions were routinely scheduled to recess exactly three months afterward in early December but were resumed in January and extended until just before the beginning of the following sessions.

Resolutions:

See also:

The General Assembly votes on many resolutions brought forth by sponsoring states. These are generally statements symbolizing the sense of the international community about an array of world issues.

Most General Assembly resolutions are not enforceable as a legal or practical matter, because the General Assembly lacks enforcement powers with respect to most issues. The General Assembly has the authority to make final decisions in some areas such as the United Nations budget.

The General Assembly can also refer an issue to the Security Council to put in place a binding resolution.

Resolution numbering scheme:

From the First to the Thirtieth General Assembly sessions, all General Assembly resolutions were numbered consecutively, with the resolution number followed by the session number in Roman numbers (for example, Resolution 1514 (XV), which was the 1514th numbered resolution adopted by the Assembly, and was adopted at the Fifteenth Regular Session (1960)).

Beginning in the Thirty-First Session, resolutions are numbered by individual session (for example Resolution 41/10 represents the 10th resolution adopted at the Forty-First Session).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the General Assembly:

Click here for List of specialized agencies of the United Nations.

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization tasked to promote international co-operation and to create and maintain international order. A replacement for the ineffective League of Nations, the organization was established on 24 October 1945 after World War II in order to prevent another such conflict.

At its founding, the UN had 51 member states; there are now 193. The headquarters of the UN is in Manhattan, New York City, and is subject to extraterritoriality. Further main offices are situated in Geneva, Nairobi, and Vienna.

The organization is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from its member states. Its objectives include maintaining international peace and security, promoting human rights, fostering social and economic development, protecting the environment, and providing humanitarian aid in cases of famine, natural disaster, and armed conflict. The UN is the largest, most familiar, most internationally represented and most powerful intergovernmental organization in the world.

The UN Charter was drafted at a conference between April–June 1945 in San Francisco, and was signed on 26 June 1945 at the conclusion of the conference; this charter took effect 24 October 1945, and the UN began operation. The UN's mission to preserve world peace was complicated in its early decades by the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union and their respective allies.

The organization participated in major actions in Korea and the Congo, as well as approving the creation of the state of Israel in 1947. The organization's membership grew significantly following widespread decolonization in the 1960s, and by the 1970s its budget for economic and social development programs far outstripped its spending on peacekeeping. After the end of the Cold War, the UN took on major military and peacekeeping missions across the world with varying degrees of success.

The UN has six principal organs:

- the General Assembly (the main deliberative assembly);

- the Security Council (See Next Topic: for deciding certain resolutions for peace and security);

- the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC; for promoting international economic and social co-operation and development);

- the Secretariat (for providing studies, information, and facilities needed by the UN);

- the International Court of Justice (the primary judicial organ);

- and the UN Trusteeship Council (inactive since 1994).

UN System agencies include:

- the World Bank Group,

- the World Health Organization,

- the World Food Program,

- UNESCO,

- and UNICEF.

The UN's most prominent officer is the Secretary-General, an office held by Portuguese António Guterres since 2017.

Non-governmental organizations may be granted consultative status with ECOSOC and other agencies to participate in the UN's work.

The organization won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, and a number of its officers and agencies have also been awarded the prize.

Other evaluations of the UN's effectiveness have been mixed. Some commentators believe the organization to be an important force for peace and human development, while others have called the organization ineffective, corrupt, or biased.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United Nations:

- History

- Background

1942 "Declaration of United Nations" by the Allies of World War II

Founding

Cold War era

Post-Cold War

- Background

- Structure

- General Assembly

Security Council

Secretariat

International Court of Justice

Economic and Social Council

Specialized agencies

- General Assembly

- Membership

- Group of 77

- Objectives

- Funding

- Evaluations, awards, and criticism

- See also:

- International relations

- List of current Permanent Representatives to the United Nations

- Model United Nations

- United Nations in popular culture

- United Nations television film series

- World Summit on the Information Society

- List of country groupings

- List of multilateral free-trade agreements

- Official websites

- Other

- Searchable archive of UN discussions and votes

- United Nations Association of the UK – independent policy authority on the UN

- Website of the Global Policy Forum, an independent think tank on the UN

- UN Watch – NGO monitoring UN activities

- Works by or about United Nations at Internet Archive

- Works by United Nations at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

United Nations Security Council:

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations, charged with the maintenance of international peace and security as well as accepting new members to the United Nations and approving any changes to its United Nations Charter.

Its powers include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of international sanctions, and the authorization of military action through Security Council resolutions; it is the only UN body with the authority to issue binding resolutions to member states.

The Security Council held its first session on 17 January 1946.

Like the UN as a whole, the Security Council was created following World War II to address the failings of a previous international organization, the League of Nations, in maintaining world peace.

In its early decades, the Security Council was largely paralyzed by the Cold War division between the US and USSR and their respective allies, though it authorized interventions in the Korean War and the Congo Crisis and peacekeeping missions in the Suez Crisis, Cyprus, and West New Guinea.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, UN peacekeeping efforts increased dramatically in scale, and the Security Council authorized major military and peacekeeping missions in Kuwait, Namibia, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Security Council consists of fifteen members. The great powers that were the victors of World War II—the Soviet Union (now represented by the Russian Federation), the United Kingdom, France, the Republic of China (now represented by the People's Republic of China), and the United States—serve as the body's five permanent members.

These permanent members can veto any substantive Security Council resolution, including those on the admission of new member states or candidates for Secretary-General.

The Security Council also has 10 non-permanent members, elected on a regional basis to serve two-year terms. The body's presidency rotates monthly among its members.

Security Council resolutions are typically enforced by UN peacekeepers, military forces voluntarily provided by member states and funded independently of the main UN budget.

As of 2016, 103,510 peacekeepers and 16,471 civilians were deployed on sixteen peacekeeping operations and one special political mission.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the NATO Security Council:

- History

- Role

- Members

- Meeting locations

- Subsidiary organs/bodies

- United Nations peacekeepers

- Criticism and evaluations

- Membership reform

- See also:

- Reform of the United Nations

- United Nations Department of Political Affairs, provides secretarial support to the Security Council

- United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee, a standing committee of the Security Council

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; French: Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 78th session, its powers, composition, functions, and procedures are set out in Chapter IV of the United Nations Charter.

The UNGA is responsible for the UN budget, appointing the non-permanent members to the Security Council, appointing the UN secretary-general, receiving reports from other parts of the UN system, and making recommendations through resolutions. It also establishes numerous subsidiary organs to advance or assist in its broad mandate. The UNGA is the only UN organ where all member states have equal representation.

The General Assembly meets under its President or the UN secretary-general in annual sessions at the General Assembly Building, within the UN headquarters in New York City.

The main part of these meetings generally runs from September through part of January until all issues are addressed, which is often before the next session starts. It can also reconvene for special and emergency special sessions. The first session was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of the 51 founding nations.

Most questions are decided in the General Assembly by a simple majority. Each member country has one vote. Voting on certain important questions—namely recommendations on peace and security; budgetary concerns; and the election, admission, suspension, or expulsion of members—is by a two-thirds majority of those present and voting. Apart from the approval of budgetary matters, including the adoption of a scale of assessment, Assembly resolutions are not binding on the members.

The Assembly may make recommendations on any matters within the scope of the UN, except matters of peace and security under the Security Council's consideration.

During the 1980s, the Assembly became a forum for "North-South dialogue" between industrialized nations and developing countries on a range of international issues. These issues came to the fore because of the phenomenal growth and changing makeup of the UN membership. In 1945, the UN had 51 members, which by the 21st century nearly quadrupled to 193, of which more than two-thirds are developing countries.

Because of their numbers, developing countries are often able to determine the agenda of the Assembly (using coordinating groups like the G77), the character of its debates, and the nature of its decisions. For many developing countries, the UN is the source of much of their diplomatic influence and the principal outlet for their foreign relations initiatives.

Although the resolutions passed by the General Assembly do not have the binding forces over the member nations (apart from budgetary measures), pursuant to its Uniting for Peace resolution of November 1950 (resolution 377 (V)), the Assembly may also take action if the Security Council fails to act, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member, in a case where there appears to be a threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression.

The Assembly can consider the matter immediately with a view to making recommendations to Members for collective measures to maintain or restore international peace and security.

Membership:

Main article: Member states of the United Nations

All 193 members of the United Nations are members of the General Assembly, with the addition of the Holy See and Palestine as observer states as well as the European Union (since 1974). Further, the United Nations General Assembly may grant observer status to an international organization or entity, which entitles the entity to participate in the work of the United Nations General Assembly, though with limitations.

Agenda:

The agenda for each session is planned up to seven months in advance and begins with the release of a preliminary list of items to be included in the provisional agenda. This is refined into a provisional agenda 60 days before the opening of the session.

After the session begins, the final agenda is adopted in a plenary meeting which allocates the work to the various main committees, who later submit reports back to the Assembly for adoption by consensus or by vote.

Items on the agenda are numbered. Regular plenary sessions of the General Assembly in recent years have initially been scheduled to be held over the course of just three months; however, additional workloads have extended these sessions until just short of the next session.

The routinely scheduled portions of the sessions normally commence on "the Tuesday of the third week in September, counting from the first week that contains at least one working day", per the UN Rules of Procedure. The last two of these Regular sessions were routinely scheduled to recess exactly three months afterward in early December but were resumed in January and extended until just before the beginning of the following sessions.

Resolutions:

See also:

The General Assembly votes on many resolutions brought forth by sponsoring states. These are generally statements symbolizing the sense of the international community about an array of world issues.

Most General Assembly resolutions are not enforceable as a legal or practical matter, because the General Assembly lacks enforcement powers with respect to most issues. The General Assembly has the authority to make final decisions in some areas such as the United Nations budget.

The General Assembly can also refer an issue to the Security Council to put in place a binding resolution.

Resolution numbering scheme:

From the First to the Thirtieth General Assembly sessions, all General Assembly resolutions were numbered consecutively, with the resolution number followed by the session number in Roman numbers (for example, Resolution 1514 (XV), which was the 1514th numbered resolution adopted by the Assembly, and was adopted at the Fifteenth Regular Session (1960)).

Beginning in the Thirty-First Session, resolutions are numbered by individual session (for example Resolution 41/10 represents the 10th resolution adopted at the Forty-First Session).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the General Assembly:

- History

- Budget

- Elections

- Sessions

- Subsidiary organs

- Seating

- Reform and UNPA

- Sidelines of the General Assembly

- See also:

- History of the United Nations

- List of current permanent representatives to the United Nations

- Reform of the United Nations

- United Nations Interpretation Service

- United Nations System

- United Nations General Assembly

- Verbatim record of the 1st session of the UN General Assembly, Jan. 1946

- UN Democracy: hyper linked transcripts of the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council

- UN General Assembly – Documentation Research Guide

- Council on Foreign Relations: The Role of the UN General Assembly

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), including its Member States

- YouTube Video: Why Does NATO Matter? | Velshi & Ruhle | MSNBC

- YouTube Video: Israel-Hamas war tops agenda at NATO defence ministers' meeting in Brussels

- YouTube Video: NATO Secretary General with the President of Ukraine 🇺🇦 Volodymyr Zelenskyy, 11 OCT 2023

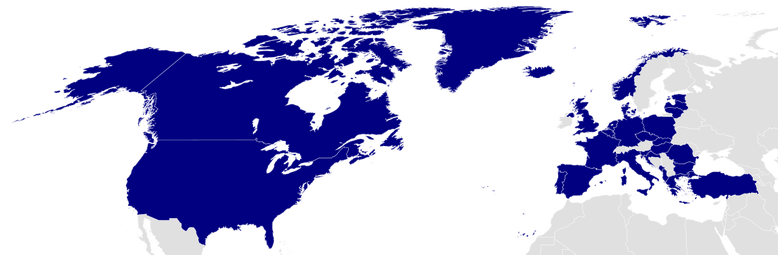

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 29 North American and European countries.

The alliance is based on the North Atlantic Treaty that was signed on 4 April 1949. NATO constitutes a system of collective defense whereby its independent member states agree to mutual defende in response to an attack by any external party.

NATO Headquarters are located in Haren, Brussels, Belgium, while the headquarters of Allied Command Operations is near Mons, Belgium.

NATO was little more than a political association until the Korean War galvanized the organization's member states, and an integrated military structure was built up under the direction of two US Supreme Commanders. The course of the Cold War led to a rivalry with nations of the Warsaw Pact which formed in 1955.

Doubts over the strength of the relationship between the European states and the United States ebbed and flowed, along with doubts over the credibility of the NATO defense against a prospective Soviet invasion—doubts that led to the development of the independent French nuclear deterrent and the withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure in 1966 for 30 years.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany in 1989, the organization conducted its first military interventions in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 and later Yugoslavia in 1999 during the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Politically, the organization sought better relations with former Warsaw Pact countries, several of which joined the alliance in 1999 and 2004.

Article 5 of the North Atlantic treaty, requiring member states to come to the aid of any member state subject to an armed attack, was invoked for the first and only time after the September 11 attacks, after which troops were deployed to Afghanistan under the NATO-led ISAF.

The organization has operated a range of additional roles since then, including sending trainers to Iraq, assisting in counter-piracy operations and in 2011 enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1973.

The less potent Article 4, which merely invokes consultation among NATO members, has been invoked five times following incidents in the Iraq War, Syrian Civil War, and annexation of Crimea.

Since its founding, the admission of new member states has increased the alliance from the original 12 countries to 29. The most recent member state to be added to NATO is Montenegro on 5 June 2017.

NATO currently recognizes Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Macedonia and Ukraine as aspiring members. An additional 21 countries participate in NATO's Partnership for Peace program, with 15 other countries involved in institutionalized dialogue programs. The combined military spending of all NATO members constitutes over 70% of the global total.

Members' defense spending is supposed to amount to at least 2% of GDP by 2024.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO):

NATO Member States:

NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) is an international alliance that consists of 29 member states from North America and Europe. It was established at the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949. Article Five of the treaty states that if an armed attack occurs against one of the member states, it should be considered an attack against all members, and other members shall assist the attacked member, with armed forces if necessary.

Of the 29 member countries, two are located in North America (Canada and the United States) and 27 are European countries while Turkey is in Eurasia. All members have militaries, except for Iceland which does not have a typical army (but does, however, have a coast guard and a small unit of civilian specialists for NATO operations).

Three of NATO's members are nuclear weapons states: France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. NATO has 12 original founding member nation states, and from 18 February 1952 to 6 May 1955, it added three more member nations, and a fourth on 30 May 1982.

After the end of the Cold War, NATO added 13 more member nations (10 former Warsaw Pact members and three former Yugoslav republics) from 12 March 1999 to 5 June 2017.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Member States of NATO:

The alliance is based on the North Atlantic Treaty that was signed on 4 April 1949. NATO constitutes a system of collective defense whereby its independent member states agree to mutual defende in response to an attack by any external party.

NATO Headquarters are located in Haren, Brussels, Belgium, while the headquarters of Allied Command Operations is near Mons, Belgium.

NATO was little more than a political association until the Korean War galvanized the organization's member states, and an integrated military structure was built up under the direction of two US Supreme Commanders. The course of the Cold War led to a rivalry with nations of the Warsaw Pact which formed in 1955.

Doubts over the strength of the relationship between the European states and the United States ebbed and flowed, along with doubts over the credibility of the NATO defense against a prospective Soviet invasion—doubts that led to the development of the independent French nuclear deterrent and the withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure in 1966 for 30 years.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany in 1989, the organization conducted its first military interventions in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 and later Yugoslavia in 1999 during the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Politically, the organization sought better relations with former Warsaw Pact countries, several of which joined the alliance in 1999 and 2004.

Article 5 of the North Atlantic treaty, requiring member states to come to the aid of any member state subject to an armed attack, was invoked for the first and only time after the September 11 attacks, after which troops were deployed to Afghanistan under the NATO-led ISAF.

The organization has operated a range of additional roles since then, including sending trainers to Iraq, assisting in counter-piracy operations and in 2011 enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1973.

The less potent Article 4, which merely invokes consultation among NATO members, has been invoked five times following incidents in the Iraq War, Syrian Civil War, and annexation of Crimea.

Since its founding, the admission of new member states has increased the alliance from the original 12 countries to 29. The most recent member state to be added to NATO is Montenegro on 5 June 2017.

NATO currently recognizes Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Macedonia and Ukraine as aspiring members. An additional 21 countries participate in NATO's Partnership for Peace program, with 15 other countries involved in institutionalized dialogue programs. The combined military spending of all NATO members constitutes over 70% of the global total.

Members' defense spending is supposed to amount to at least 2% of GDP by 2024.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO):

- History

- Military operations

- Participating countries

- Structures

- See also:

- NATO portal

- Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition

- Ranks and insignia of NATO

- Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union

- Official website

- Collected news:

- History:

- "Timeline: Nato – A brief look at some of the key dates in the organisation's history" by The Guardian's Simon Jeffery on 11 February 2003

- Historic films:

- The short film Big Picture: Why NATO? is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film Big Picture: NATO Maneuvers is available for free download at the Internet Archive

NATO Member States:

NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) is an international alliance that consists of 29 member states from North America and Europe. It was established at the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949. Article Five of the treaty states that if an armed attack occurs against one of the member states, it should be considered an attack against all members, and other members shall assist the attacked member, with armed forces if necessary.

Of the 29 member countries, two are located in North America (Canada and the United States) and 27 are European countries while Turkey is in Eurasia. All members have militaries, except for Iceland which does not have a typical army (but does, however, have a coast guard and a small unit of civilian specialists for NATO operations).

Three of NATO's members are nuclear weapons states: France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. NATO has 12 original founding member nation states, and from 18 February 1952 to 6 May 1955, it added three more member nations, and a fourth on 30 May 1982.

After the end of the Cold War, NATO added 13 more member nations (10 former Warsaw Pact members and three former Yugoslav republics) from 12 March 1999 to 5 June 2017.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Member States of NATO:

- Founding and changes in membership

- Member states by date of membership

- Military personnel

- Military expenditures

Representative Democracies, e.g., The United States, which is a Federal Republic

- YouTube Video: What is Representative Democracy?

- YouTube Video: For the People? Representative Government in America

- YouTube Video: The German Bundestag: The Heart of Democracy

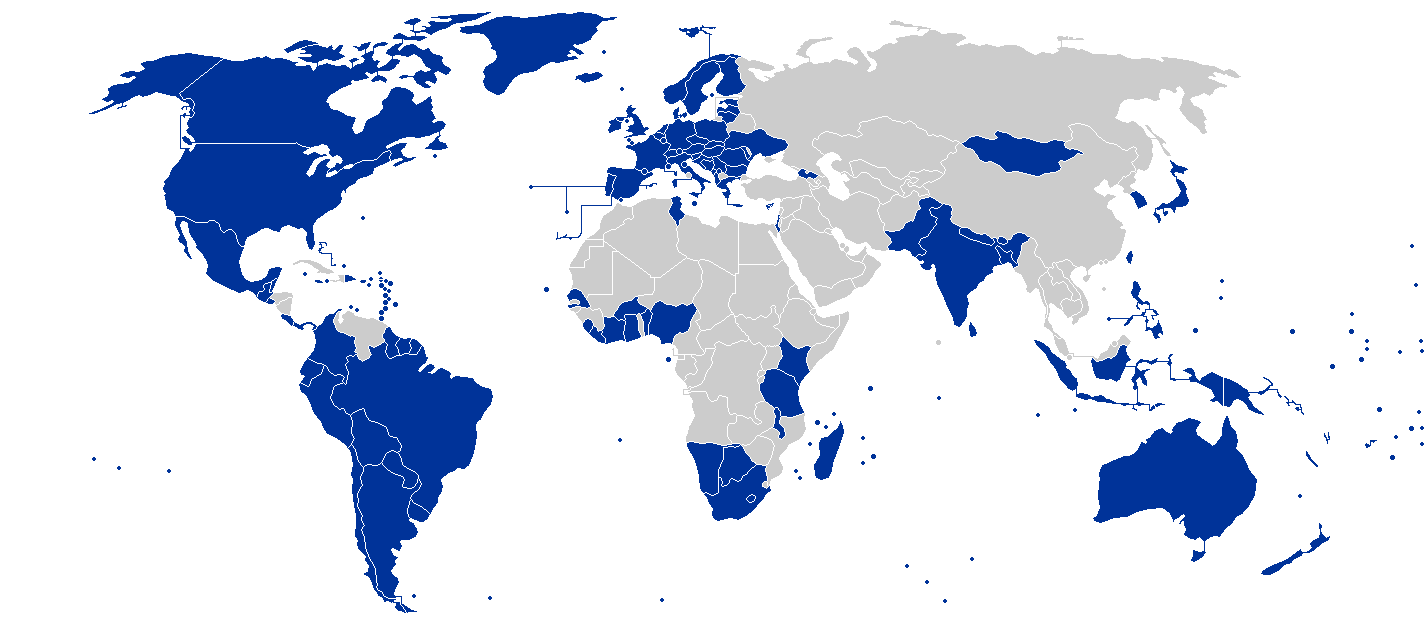

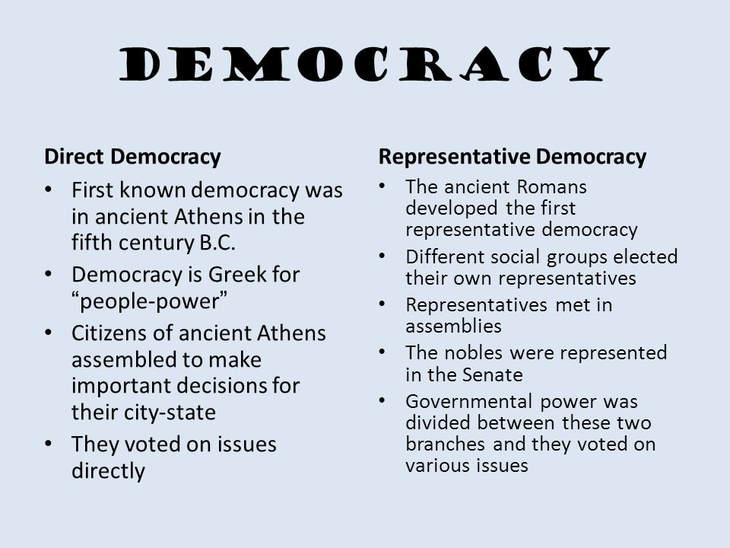

Representative democracy (also indirect democracy, representative republic, representative government or psephocracy) is a type of democracy founded on the principle of elected officials representing a group of people, as opposed to direct democracy.

Nearly all modern Western-style democracies are types of representative democracies; for example, the United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy, France is a unitary state, and the United States is a federal republic.

It is an element of both the parliamentary and the presidential systems of government and is typically used in a lower chamber such as the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, Lok Sabha of India, and may be curtailed by constitutional constraints such as an upper chamber.

It has been described by some political theorists including Robert A. Dahl, Gregory Houston and Ian Liebenberg as polyarchy. In it the power is in the hands of the representatives who are elected by the people.

Powers of Representatives:

Representatives are elected by the public, as in national elections for the national legislature. Elected representatives may hold the power to select other representatives, presidents, or other officers of the government or of the legislature, as the Prime Minister in the latter case. (indirect representation).

The power of representatives is usually curtailed by a constitution (as in a constitutional democracy or a constitutional monarchy) or other measures to balance representative power:

Theorists such as Edmund Burke believe that part of the duty of a representative was not simply to communicate the wishes of the electorate but also to use their own judgement in the exercise of their powers, even if their views are not reflective of those of a majority of voters:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Representative Democracy:

Nearly all modern Western-style democracies are types of representative democracies; for example, the United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy, France is a unitary state, and the United States is a federal republic.

It is an element of both the parliamentary and the presidential systems of government and is typically used in a lower chamber such as the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, Lok Sabha of India, and may be curtailed by constitutional constraints such as an upper chamber.

It has been described by some political theorists including Robert A. Dahl, Gregory Houston and Ian Liebenberg as polyarchy. In it the power is in the hands of the representatives who are elected by the people.

Powers of Representatives:

Representatives are elected by the public, as in national elections for the national legislature. Elected representatives may hold the power to select other representatives, presidents, or other officers of the government or of the legislature, as the Prime Minister in the latter case. (indirect representation).

The power of representatives is usually curtailed by a constitution (as in a constitutional democracy or a constitutional monarchy) or other measures to balance representative power:

- An independent judiciary, which may have the power to declare legislative acts unconstitutional (e.g. constitutional court, supreme court).