Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Herein, we cover

Politics,

in support of the freedoms that our Founding Fathers envisioned and implemented through the American Constitution calling for representative Democracy for All!

See Also Web Pages:

"Our Free Press"

"American Democracy"

Politics, including Politics in the United States

- YouTube Video: 10 Signs You Should Become A Politician

- YouTube Video: How to Win an Election: Political Campaign

- YouTube Video: The wildest political moments of 2019

Politics (from Greek: Πολιτικά, politiká, 'affairs of the cities') is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The academic study of politics is referred to as political science.

It may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and non-violent, or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but also often carries a negative connotation. For example, abolitionist Wendell Phillips declared that "we do not play politics; anti-slavery is no half-jest with us."

The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or limitedly, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it.

A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation with other political subjects, making laws, and exercising force, including warfare against adversaries. Politics is exercised on a wide range of social levels, from clans and tribes of traditional societies, through modern local governments, companies and institutions up to sovereign states, to the international level.

In modern nation states, people often form political parties to represent their ideas. Members of a party often agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support the same changes to law and the same leaders. An election is usually a competition between different parties.

A political system is a framework which defines acceptable political methods within a society. The history of political thought can be traced back to early antiquity, with seminal works such as Plato's Republic, Aristotle's Politics, Chanakya's Arthashastra and Chanakya Niti (3rd century BCE), as well as the works of Confucius.

Etymology:

The English politics has its roots in the name of Aristotle's classic work, Politiká, which introduced the Greek term politiká (Πολιτικά, 'affairs of the cities'). In the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition would be rendered in Early Modern English as Polettiques which would become Politics in Modern English.

The singular politic first attested in English in 1430, coming from Middle French politique—itself taking from politicus, a Latinization of the Greek πολιτικός (politikos) from πολίτης (polites, 'citizen') and πόλις (polis, 'city').

Definitions:

Approaches:

There are several ways in which approaching politics has been conceptualized.

Extensive and limited:

Adrian Leftwich has differentiated views of politics based on how extensive or limited their perception of what accounts as 'political' is. The extensive view sees politics as present across the sphere of human social relations, while the limited view restricts it to certain contexts.

For example, in a more restrictive way, politics may be viewed as primarily about governance, while a feminist perspective could argue that sites which have been viewed traditionally as non-political, should indeed be viewed as political as well.

This latter position is encapsulated in the slogan the personal is political, which disputes the distinction between private and public issues. Instead, politics may be defined by the use of power, as has been argued by Robert A. Dahl.

Moralism and realism:

Some perspectives on politics view it empirically as an exercise of power, while other see it as a social function with a normative basis. This distinction has been called the difference between political moralism and political realism.

For moralists, politics is closely linked to ethics, and is at its extreme in utopian thinking. For example, according to Hannah Arendt, the view of Aristotle was that "to be political…meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through violence;" while according to Bernard Crick "[p]olitics is the way in which free societies are governed. Politics is politics and other forms of rule are something else."

In contrast, for realists, represented by those such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Harold Lasswell, politics is based on the use of power, irrespective of the ends being pursued.

Conflict and co-operation:

Agonism argues that politics essentially comes down to conflict between conflicting interests. Political scientist Elmer Schattschneider argued that "at the root of all politics is the universal language of conflict," while for Carl Schmitt the essence of politics is the distinction of 'friend' from foe'.

This is in direct contrast to the more co-operative views of politics by Aristotle and Crick. However, a more mixed view between these extremes is provided by Irish author Michael Laver, who noted that: Politics is about the characteristic blend of conflict and co-operation that can be found so often in human interactions. Pure conflict is war. Pure co-operation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.

Political science:

Main article: Political science

The study of politics is called political science, or politology. It comprises numerous subfields, including:

Furthermore, political science is related to, and draws upon, the fields of

Comparative politics is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields, all of them from an intrastate perspective.

International relations deals with the interaction between nation-states as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations. Political philosophy is more concerned with contributions of various classical and contemporary thinkers and philosophers.

Political science is methodologically diverse and appropriates many methods originating in psychology, social research, and cognitive neuroscience.

Approaches include

Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, experimental research, and model building.

Political system:

Main article: Political system

See also: Systems theory in political science

The political system defines the process for making official government decisions. It is usually compared to the legal system, economic system, cultural system, and other social systems.

According to David Easton, "A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society." Each political system is embedded in a society with its own political culture, and they in turn shape their societies through public policy. The interactions between different political systems are the basis for global politics.

Forms of government:

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and republics (usually presidential, semi-presidential, or parliamentary).

The separation of powers describes the degree of horizontal integration between the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, and other independent institutions.

Source of power:

The source of power determines the difference between democracies, oligarchies, and autocracies.

In a democracy, political legitimacy is based on popular sovereignty. Forms of democracy include representative democracy, direct democracy, and demarchy. These are separated by the way decisions are made, whether by elected representatives, referenda, or by citizen juries.

Democracies can be either republics or constitutional monarchies.

Oligarchy is a power structure where a minority rules. These may be in the form of:

Autocracies are either dictatorships (including military dictatorships) or absolute monarchies.

Vertical integration: In terms of level of vertical integration, political systems can be divided into (from least to most integrated) confederations, federations, and unitary states.

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism).

In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body.

Federations were formed first in Switzerland, then in the United States in 1776, in Canada in 1867 and in Germany in 1871 and in 1901, Australia. Compared to a federation, a confederation has less centralized power.

State:

All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic polity, the sovereign state. The state has been defined by Max Weber as a political entity that has monopoly on violence within its territory, while the Montevideo Convention holds that states need to have a defined territory; a permanent population; a government; and a capacity to enter into international relations.

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small. Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.

While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state.

In some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.

Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved. A central tenet of anarchism is the advocacy of society without states. The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought, ranging from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.

In Marxism, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and wither away. A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society.

Constitutions:

Constitutions are written documents that specify and limit the powers of the different branches of government. Although a constitution is a written document, there is also an unwritten constitution.

The unwritten constitution is continually being written by the legislative and judiciary branch of government; this is just one of those cases in which the nature of the circumstances determines the form of government that is most appropriate.

England did set the fashion of written constitutions during the Civil War but after the Restoration abandoned them to be taken up later by the American Colonies after their emancipation and then France after the Revolution and the rest of Europe including the European colonies.

Constitutions often set out separation of powers, dividing the government into the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary (together referred to as the trias politica), in order to achieve checks and balances within the state. Additional independent branches may also be created, including civil service commissions, election commissions, and supreme audit institutions.

Political culture:

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system is embedded in a particular political culture. Lucian Pye's definition is that "Political culture is the set of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments, which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behavior in the political system".

Trust is a major factor in political culture, as its level determines the capacity of the state to function. Postmaterialism is the degree to which a political culture is concerned with issues which are not of immediate physical or material concern, such as human rights and environmentalism. Religion has also an impact on political culture.

Political dysfunction:

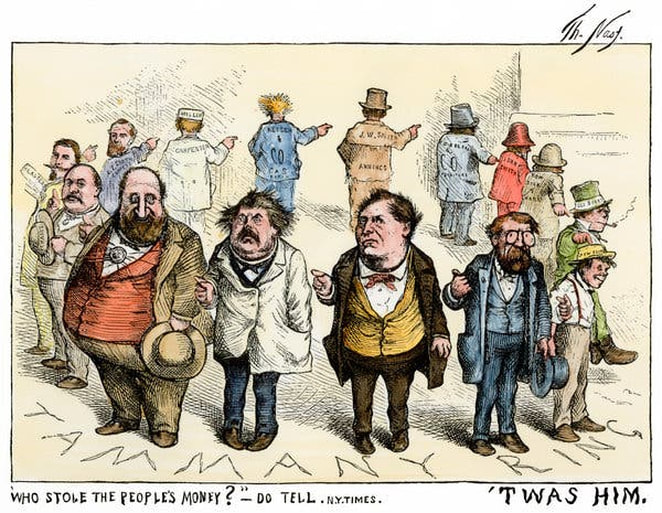

Political corruption:

Main article: Political corruption

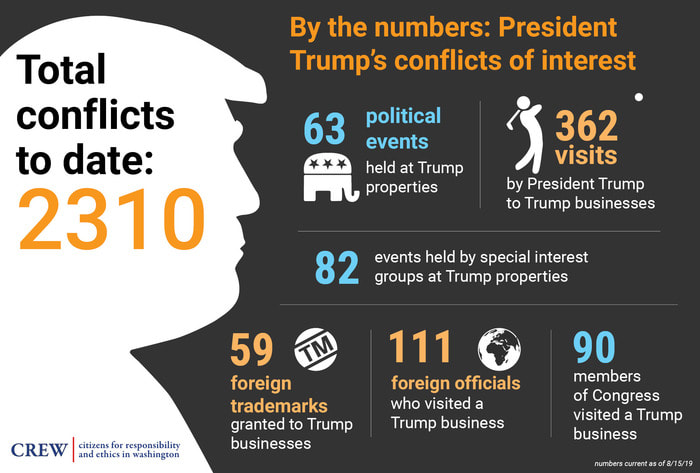

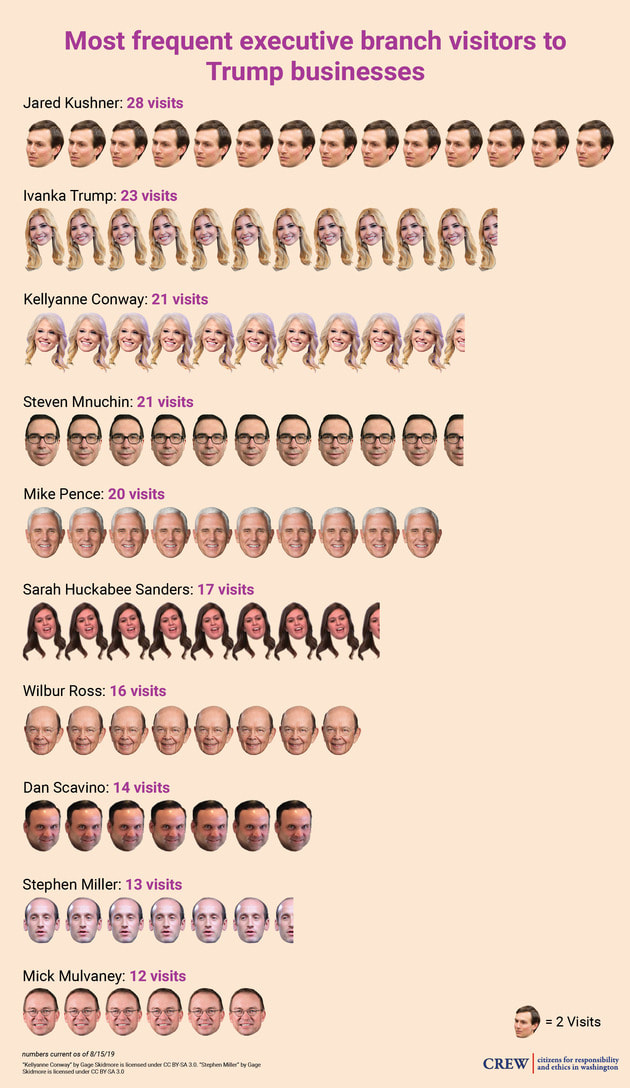

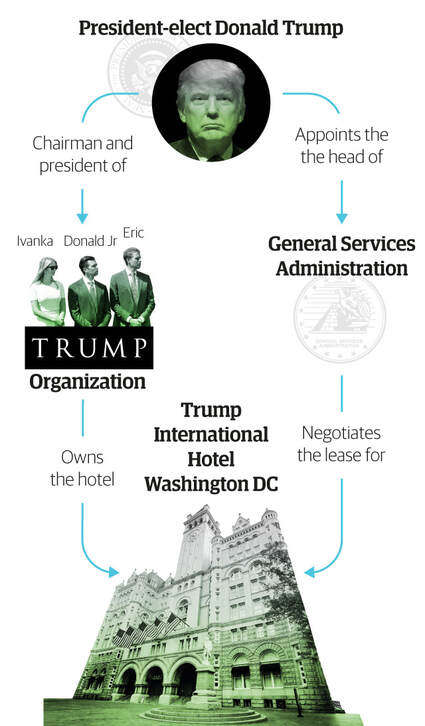

Political corruption is the use of powers for illegitimate private gain, conducted by government officials or their network contacts. Forms of political corruption include bribery, cronyism, nepotism, and political patronage.

Forms of political patronage, in turn, includes clientelism, earmarking, pork barreling, slush funds, and spoils systems; as well as political machines, which is a political system that operates for corrupt ends.

When corruption is embedded in political culture, this may be referred to as patrimonialism or neopatrimonialism. A form of government that is built on corruption is called a kleptocracy ('rule of thieves').

Political conflict:

Main article: Political conflict

Political conflict entails the use of political violence to achieve political ends. As noted by Carl von Clausewitz, "War is a mere continuation of politics by other means." Beyond just inter-state warfare, this may include civil war; wars of national liberation; or asymmetric warfare, such as guerrilla war or terrorism.

When a political system is overthrown, the event is called a revolution: it is a political revolution if it does not go further; or a social revolution if the social system is also radically altered. However, these may also be nonviolent revolutions.

Levels of politics:

Macropolitics:

Main article: Global politics

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g. international relations).

Global politics (or world politics) covers all aspects of politics that affect multiple political systems, in practice meaning any political phenomenon crossing national borders. This can include:

An important element is international relations: the relations between nation-states may be peaceful when they are conducted through diplomacy, or they may be violent, which is described as war.

States that are able to exert strong international influence are referred to as superpowers, whereas less-powerful ones may be called regional or middle powers. The international system of power is called the world order, which is affected by the balance of power that defines the degree of polarity in the system. Emerging powers are potentially destabilizing to it, especially if they display revanchism or irredentism.

Politics inside the limits of political systems, which in contemporary context correspond to national borders, are referred to as domestic politics. This includes most forms of public policy, such as social policy, economic policy, or law enforcement, which are executed by the state bureaucracy.

Mesopolitics:

Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediary structures within a political system, such as national political parties or movements.

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to attain and maintain political power within government, usually by participating in political campaigns, educational outreach, or protest actions. Parties often espouse an expressed ideology or vision, bolstered by a written platform with specific goals, forming a coalition among disparate interests.

Political parties within a particular political system together form the party system, which can be either multiparty, two-party, dominant-party, or one-party, depending on the level of pluralism. This is affected by characteristics of the political system, including its electoral system.

According to Duverger's law, first-past-the-post systems are likely to lead to two-party systems, while proportional representation systems are more likely to create a multiparty system.

Micropolitics:

Micropolitics describes the actions of individual actors within the political system. This is often described as political participation. Political participation may take many forms, including:

Political values:

Main article: Political philosophy

Democracy:

Main article: Democracy

Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes. The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy.

Democracy makes all forces struggle repeatedly to realize their interests and devolves power from groups of people to sets of rules.

Among modern political theorists, there are three contending conceptions of democracy: aggregative, deliberative, and radical.

Aggregative:

The theory of aggregative democracy claims that the aim of the democratic processes is to solicit the preferences of citizens, and aggregate them together to determine what social policies the society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented.

Different variants of aggregative democracy exist. Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens have given teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections.

According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not "rule" because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

According to the theory of direct democracy, on the other hand, citizens should vote directly, not through their representatives, on legislative proposals. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites.

Most importantly, citizens do not rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter—with half to their left and the other half to their right. This is not a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes.

Anthony Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.

Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision).

He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy.

First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society.

However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation. Similarly, Ronald Dworkin argues that "democracy is a substantive, not a merely procedural, ideal."

Deliberative:

Main article: Deliberative democracy

Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by deliberation.

Unlike aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting.

Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtained through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.

If the decision-makers cannot reach consensus after authentically deliberating on a proposal, then they vote on the proposal using a form of majority rule.

Radical:

Main article: Radical democracy

Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision-making processes.

Equality:

Main article: Social equality

Equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific society or isolated group have the same social status, especially socioeconomic status, including protection of human rights and dignity, and equal access to certain social goods and social services.

Furthermore, it may also include health equality, economic equality and other social securities. Social equality requires the absence of legally enforced social class or caste boundaries and the absence of discrimination motivated by an inalienable part of a person's identity.

To this end there must be equal justice under law, and equal opportunity regardless of, for example, sex, gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, origin, caste or class, income or property, language, religion, convictions, opinions, health or disability.

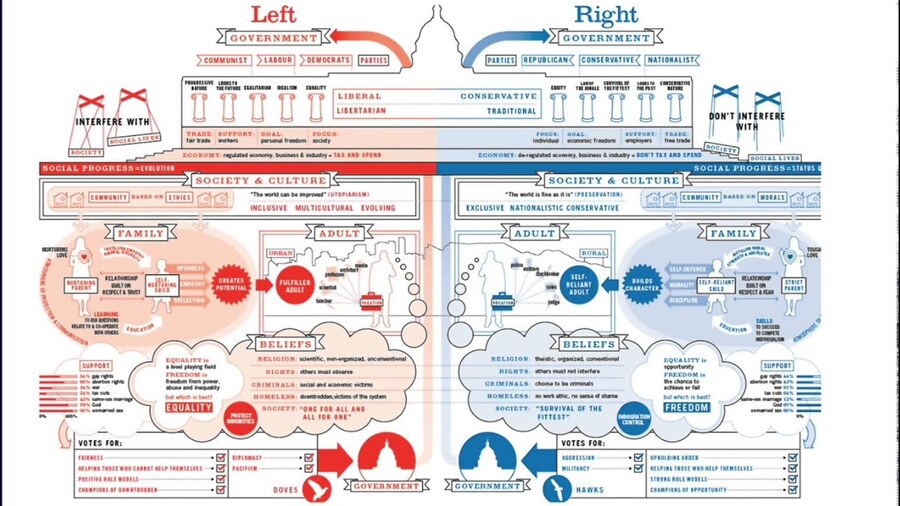

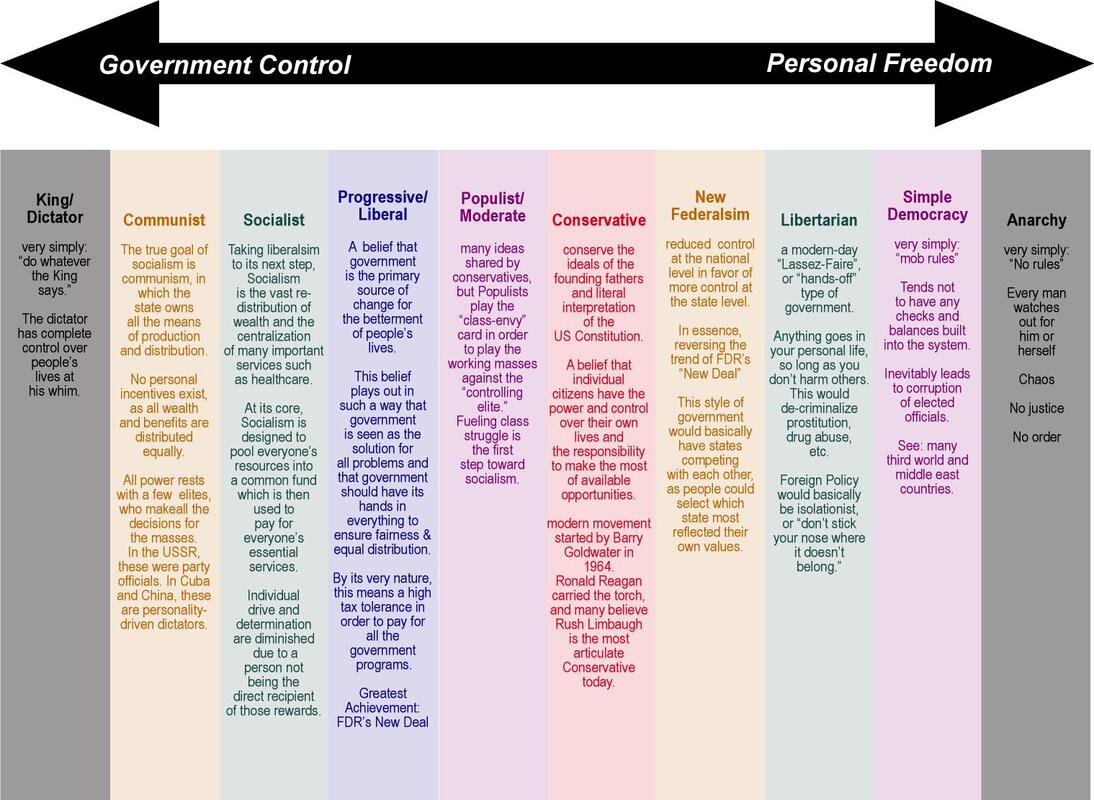

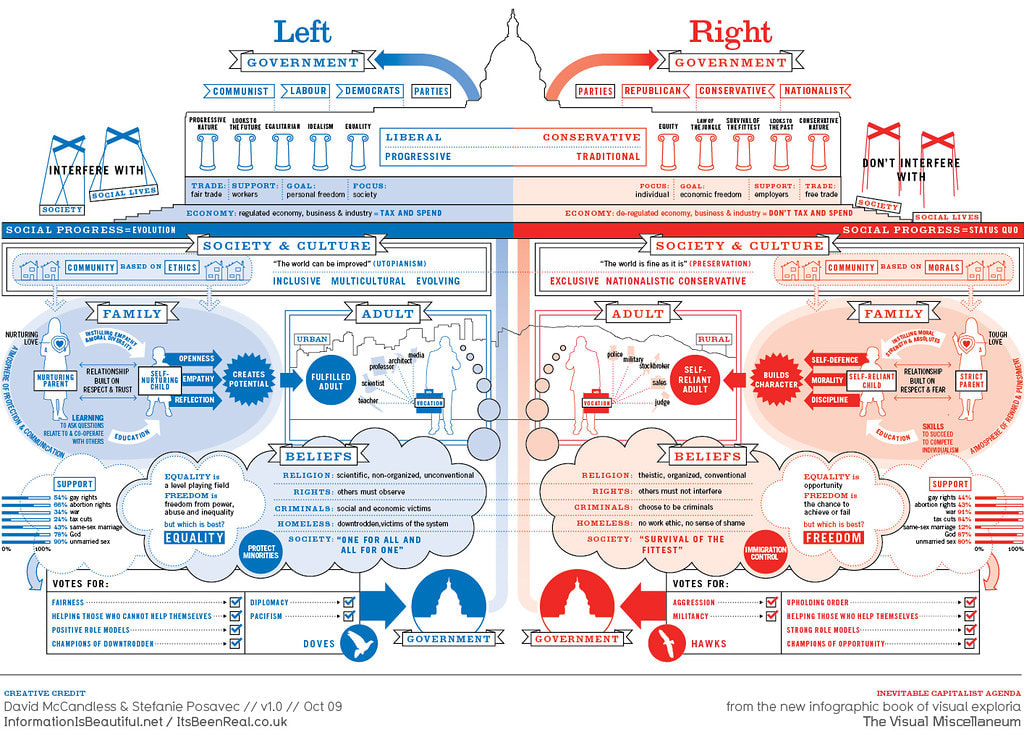

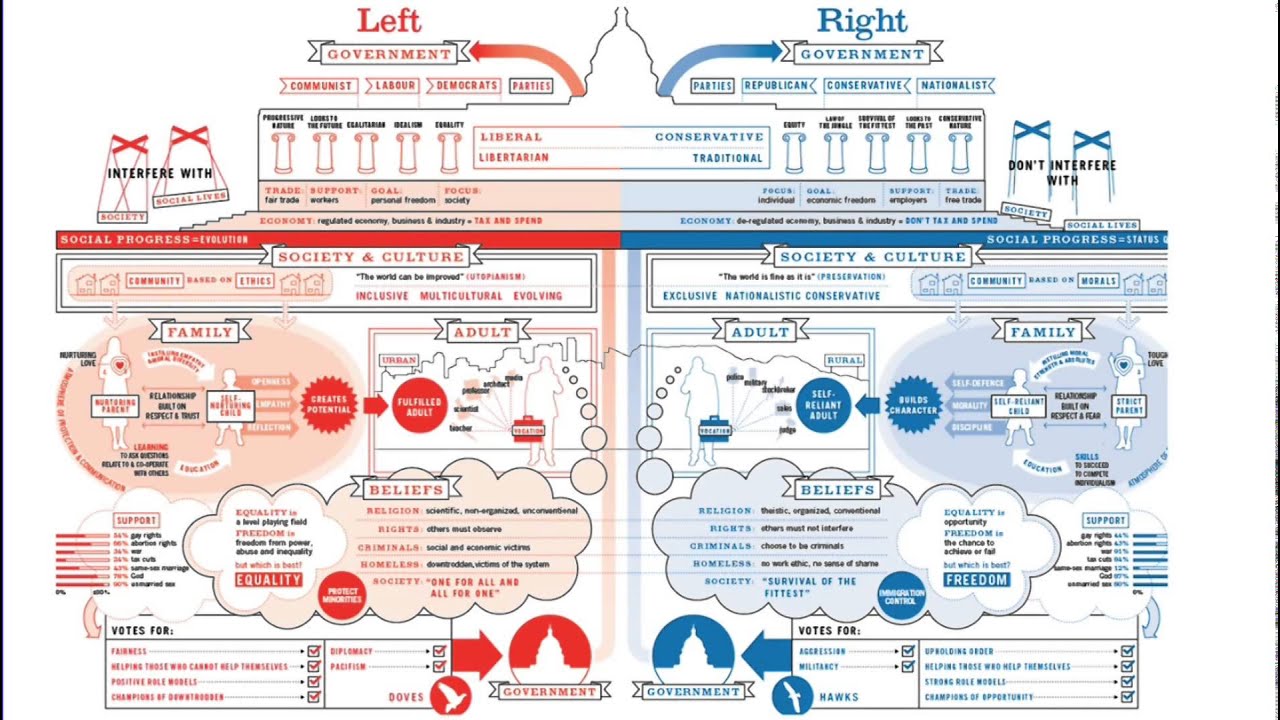

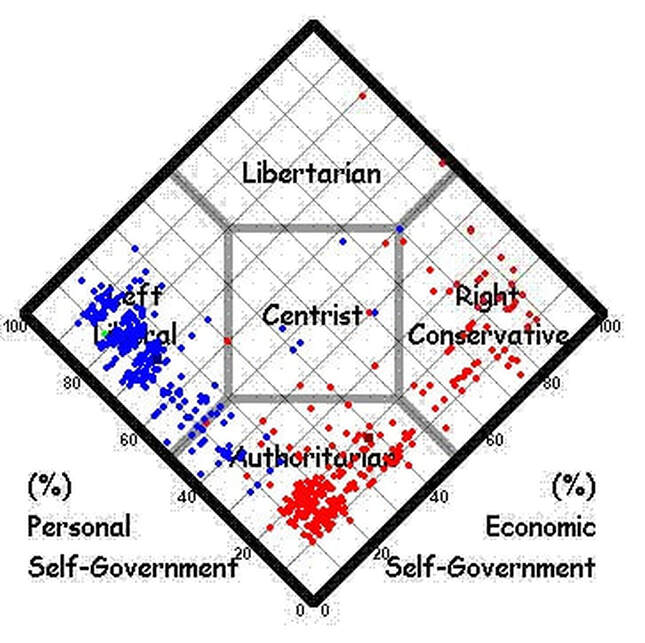

Left–right spectrum:

A common way of understanding politics is through the left–right political spectrum, which ranges from left-wing politics via centrism to right-wing politics. This classification is comparatively recent and dates from the French Revolution, when those members of the National Assembly who supported the republic, the common people and a secular society sat on the left and supporters of the monarchy, aristocratic privilege and the Church sat on the right.

Today, the left is generally progressivist, seeking social progress in society. The more extreme elements of the left, named the far-left, tend to support revolutionary means for achieving this. This includes ideologies such as Communism and Marxism. The center-left, on the other hand, advocate for more reformist approaches, for example that of social democracy.

In contrast, the right is generally motivated by conservatism, which seeks to conserve what it sees as the important elements of society. The far-right goes beyond this, and often represents a reactionary turn against progress, seeking to undo it. Examples of such ideologies have included Fascism and Nazism.

The center-right may be less clear-cut and more mixed in this regard, with neoconservatives supporting the spread of democracy, and one-nation conservatives more open to social welfare programs.

According to Norberto Bobbio, one of the major exponents of this distinction, the left believes in attempting to eradicate social inequality—believing it to be unethical or unnatural, while the right regards most social inequality as the result of ineradicable natural inequalities, and sees attempts to enforce social equality as utopian or authoritarian.

Some ideologies, notably Christian Democracy, claim to combine left and right-wing politics; according to Geoffrey K. Roberts and Patricia Hogwood, "In terms of ideology, Christian Democracy has incorporated many of the views held by liberals, conservatives and socialists within a wider framework of moral and Christian principles."

Movements which claim or formerly claimed to be above the left-right divide include Fascist Terza Posizione economic politics in Italy and Peronism in Argentina.

Freedom:

Main article: Political freedom

Political freedom (also known as political liberty or autonomy) is a central concept in political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.

Negative liberty has been described as freedom from oppression or coercion and unreasonable external constraints on action, often enacted through civil and political rights, while positive liberty is the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions, e.g. economic compulsion, in a society.

This capability approach to freedom requires economic, social and cultural rights in order to be realized.

Authoritarianism and libertarianism:

Authoritarianism and libertarianism disagree the amount of individual freedom each person possesses in that society relative to the state. One author describes authoritarian political systems as those where "individual rights and goals are subjugated to group goals, expectations and conformities," while libertarians generally oppose the state and hold the individual as sovereign.

In their purest form, libertarians are anarchists, who argue for the total abolition of the state, of political parties and of other political entities, while the purest authoritarians are, by definition, totalitarians who support state control over all aspects of society.

For instance, classical liberalism (also known as laissez-faire liberalism) is a doctrine stressing individual freedom and limited government. This includes the importance of human rationality, individual property rights, free markets, natural rights, the protection of civil liberties, constitutional limitation of government, and individual freedom from restraint as exemplified in the writings of John Locke, Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, Voltaire, Montesquieu and others.

According to the libertarian Institute for Humane Studies, "the libertarian, or 'classical liberal,' perspective is that individual well-being, prosperity, and social harmony are fostered by 'as much liberty as possible' and 'as little government as necessary.'"

For anarchist political philosopher L. Susan Brown (1993), "liberalism and anarchism are two political philosophies that are fundamentally concerned with individual freedom yet differ from one another in very distinct ways. Anarchism shares with liberalism a radical commitment to individual freedom while rejecting liberalism's competitive property relations.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Politics:

Politics of the United States

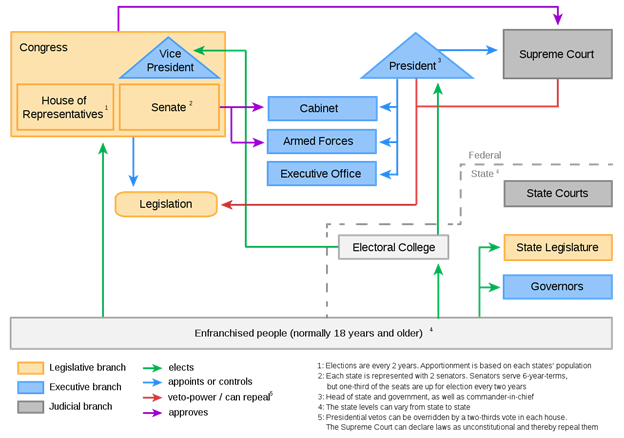

The United States is a federal constitutional republic, in which the President of the United States (the head of state and head of government), Congress, and judiciary share powers reserved to the national government, and the federal government shares sovereignty with the state governments.

The executive branch is headed by the President and is independent of the legislature.

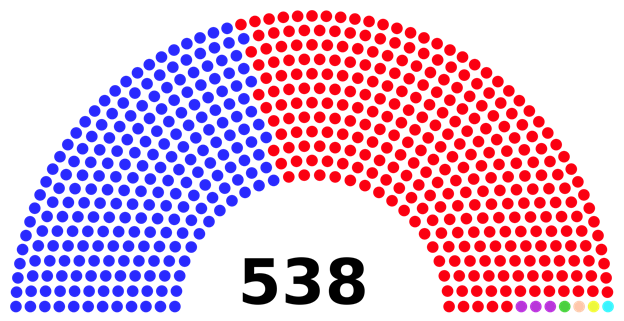

Legislative power is vested in the two chambers of Congress: the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The judicial branch (or judiciary), composed of the Supreme Court and lower federal courts, exercises judicial power. The judiciary's function is to interpret the United States Constitution and federal laws and regulations. This includes resolving disputes between the executive and legislative branches.

The federal government's layout is explained in the Constitution. Two political parties, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, have dominated American politics since the American Civil War, although other parties have also existed.

There are major differences between the political system of the United States and that of most other developed democracies. These include increased power of the upper house of the legislature, a wider scope of power held by the Supreme Court, the separation of powers between the legislature and the executive, and the dominance of only two main parties. The United States is one of the world's developed democracies where third parties have the least political influence.

The federal entity created by the U.S. Constitution is the dominant feature of the American governmental system. However, most residents are also subject to a state government, and also subject to various units of local government. The latter can include counties, municipalities, and special districts.

State government:

States governments have the power to make laws on all subjects that are not granted to the federal government or denied to the states in the U.S. Constitution. These include education, family law, contract law, and most crimes.

Unlike the federal government, which only has those powers granted to it in the Constitution, a state government has inherent powers allowing it to act unless limited by a provision of the state or national constitution.

Like the federal government, state governments have three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The chief executive of a state is its popularly elected governor, who typically holds office for a four-year term (although in some states the term is two years).

Except for Nebraska, which has unicameral legislature, all states have a bicameral legislature, with the upper house usually called the Senate and the lower house called the House of Representatives, the Assembly or something similar. In most states, senators serve four-year terms, and members of the lower house serve two-year terms.

The constitutions of the various states differ in some details but generally follow a pattern similar to that of the federal Constitution, including a statement of the rights of the people and a plan for organizing the government. However, state constitutions are generally more detailed.

Local government:

See also: Urban politics in the United States

There are 89,500 local governments, including 3,033 counties, 19,492 municipalities, 16,500 townships, 13,000 school districts, and 37,000 other special districts. Local governments directly serve the needs of the people, providing everything from police and fire protection to sanitary codes, health regulations, education, public transportation, and housing. Typically local elections are nonpartisan - local activists suspend their party affiliations when campaigning and governing.

About 28% of the people live in cities of 100,000 or more population. City governments are chartered by states, and their charters detail the objectives and powers of the municipal government.

For most big cities, cooperation with both state and federal organizations is essential to meeting the needs of their residents. Types of city governments vary widely across the nation. However, almost all have a central council, elected by the voters, and an executive officer, assisted by various department heads, to manage the city's affairs. Cities in the West and South usually have nonpartisan local politics.

There are three general types of city government: the mayor-council, the commission, and the council-manager. These are the pure forms; many cities have developed a combination of two or three of them.

Mayor-Council:

This is the oldest form of city government in the United States and, until the beginning of the 20th century, was used by nearly all American cities. Its structure is like that of the state and national governments, with an elected mayor as chief of the executive branch and an elected council that represents the various neighborhoods forming the legislative branch.

The mayor appoints heads of city departments and other officials, sometimes with the approval of the council. He or she has the power of veto over ordinances (the laws of the city) and often is responsible for preparing the city's budget. The council passes city ordinances, sets the tax rate on property, and apportions money among the various city departments. As cities have grown, council seats have usually come to represent more than a single neighborhood.

The Commission:

This combines both the legislative and executive functions in one group of officials, usually three or more in number, elected city-wide. Each commissioner supervises the work of one or more city departments. Commissioners also set policies and rules by which the city is operated. One is named chairperson of the body and is often called the mayor, although his or her power is equivalent to that of the other commissioners.

Council-Manager:

The city manager is a response to the increasing complexity of urban problems that need management ability not often possessed by elected public officials. The answer has been to entrust most of the executive powers, including law enforcement and provision of services, to a highly trained and experienced professional city manager.

The council-manager plan has been adopted by a large number of cities. Under this plan, a small, elected council makes the city ordinances and sets policy, but hires a paid administrator, also called a city manager, to carry out its decisions. The manager draws up the city budget and supervises most of the departments. Usually, there is no set term; the manager serves as long as the council is satisfied with his or her work.

County government:

The county is a subdivision of the state, sometimes (but not always) containing two or more townships and several villages. New York City is so large that it is divided into five separate boroughs, each a county in its own right.

On the other hand, Arlington County, Virginia, the United States' smallest county, located just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., is both an urbanized and suburban area, governed by a unitary county administration. In other cities, both the city and county governments have merged, creating a consolidated city–county government.

In most U.S. counties, one town or city is designated as the county seat, and this is where the government offices are located and where the board of commissioners or supervisors meets. In small counties, boards are chosen by the county; in the larger ones, supervisors represent separate districts or townships. The board collects taxes for state and local governments; borrows and appropriates money; fixes the salaries of county employees; supervises elections; builds and maintains highways and bridges; and administers national, state, and county welfare programs.

In very small counties, the executive and legislative power may lie entirely with a sole commissioner, who is assisted by boards to supervise taxes and elections. In some New England states, counties do not have any governmental function and are simply a division of land.

Town and village government:

Thousands of municipal jurisdictions are too small to qualify as city governments. These are chartered as towns and villages and deal with local needs such as paving and lighting the streets, ensuring a water supply, providing police and fire protection, and waste management.

In many states of the US, the term town does not have any specific meaning; it is simply an informal term applied to populated places (both incorporated and unincorporated municipalities). Moreover, in some states, the term town is equivalent to how civil townships are used in other states.

The government is usually entrusted to an elected board or council, which may be known by a variety of names: town or village council, board of selectmen, board of supervisors, board of commissioners. The board may have a chairperson or president who functions as chief executive officer, or there may be an elected mayor. Governmental employees may include a clerk, treasurer, police and fire officers, and health and welfare officers.

One unique aspect of local government, found mostly in the New England region of the United States, is the town meeting. Once a year, sometimes more often if needed, the registered voters of the town meet in open session to elect officers, debate local issues, and pass laws for operating the government.

As a body, they decide on road construction and repair, construction of public buildings and facilities, tax rates, and the town budget. The town meeting, which has existed for more than three centuries in some places, is often cited as the purest form of direct democracy, in which the governmental power is not delegated, but is exercised directly and regularly by all the people.

Suffrage:

Main article: Voting rights in the United States

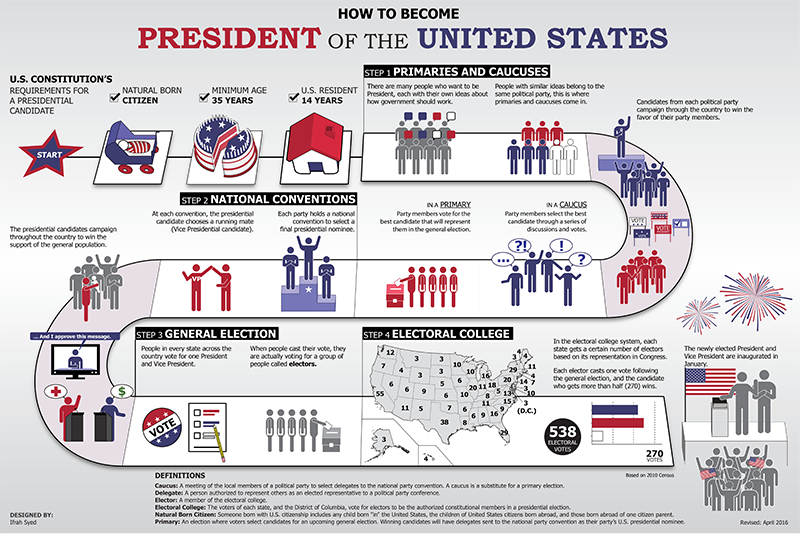

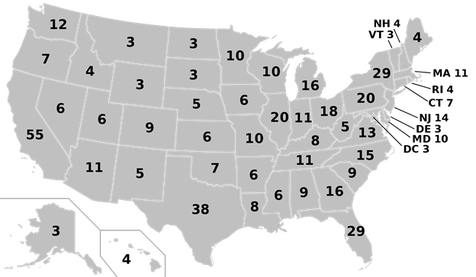

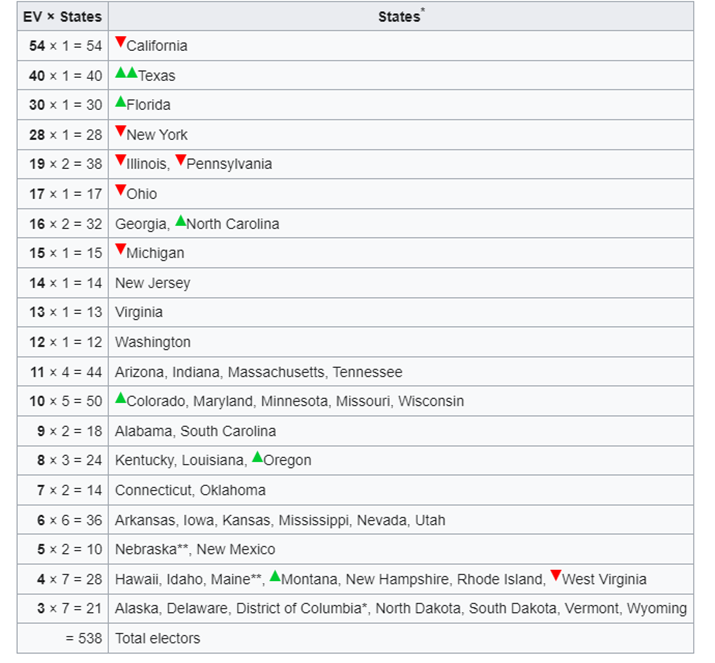

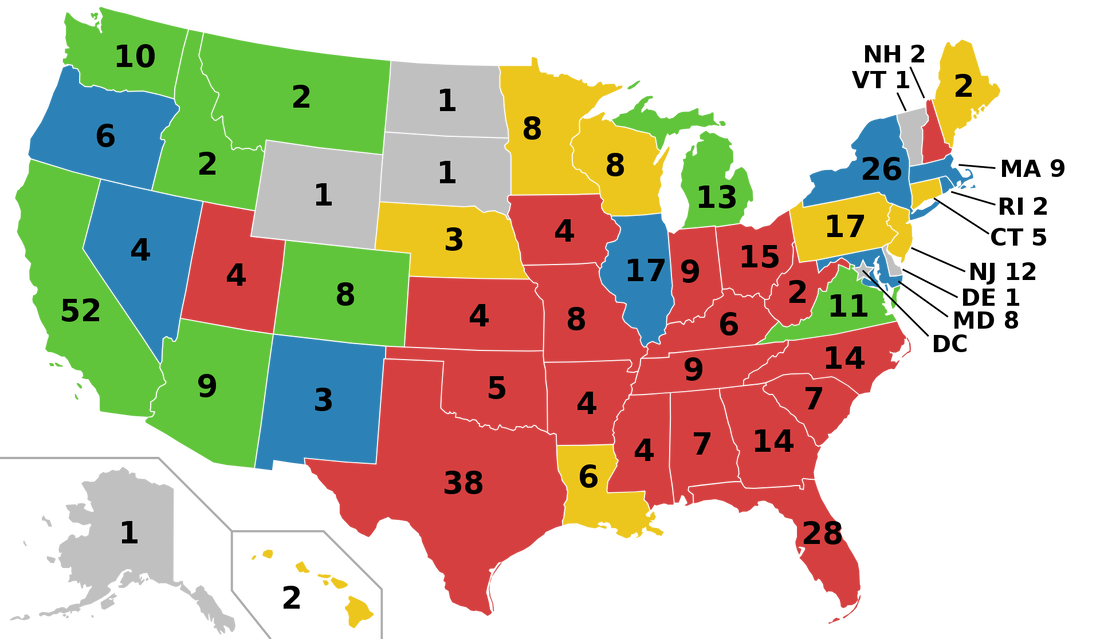

Suffrage is nearly universal for citizens 18 years of age and older. All states and the District of Columbia contribute to the electoral vote for President. However, the District, and other U.S. holdings like Puerto Rico and Guam, lack representation in Congress. These constituencies do not have the right to choose any political figure outside their respective areas. Each commonwealth, territory, or district can only elect a non-voting delegate to serve in the House of Representatives.

Voting rights are sometimes restricted as a result of felony conviction, but such laws vary widely by state. Election of the president is an indirect suffrage: voters vote for electors who comprise the United States Electoral College and who, in turn vote for President.

These presidential electors were originally expected to exercise their own judgement. In modern practice, though, they are expected to vote as pledged and some faithless electors have not.

Unincorporated areas:

Some states contain unincorporated areas, which are areas of land not governed by any local authorities and rather just by the county, state and federal governments. Residents of unincorporated areas only need to pay taxes to the county, state and federal governments as opposed to the municipal government as well. A notable example of this is Paradise, Nevada, an unincorporated area where many of the casinos commonly associated with Las Vegas are situated.

Unorganized territories:

Main article: Unorganized territory

The United States also possesses a number of unorganized territories. These are areas of land which are not under the jurisdiction of any state, and do not have a government established by Congress through an organic act. The unorganized territories of the U.S. are:

American Samoa is the only one with a native resident population, and is governed by a local authority. Despite the fact that an organic act was not passed in Congress, American Samoa established its own constitution in 1967, and has self governed ever since.

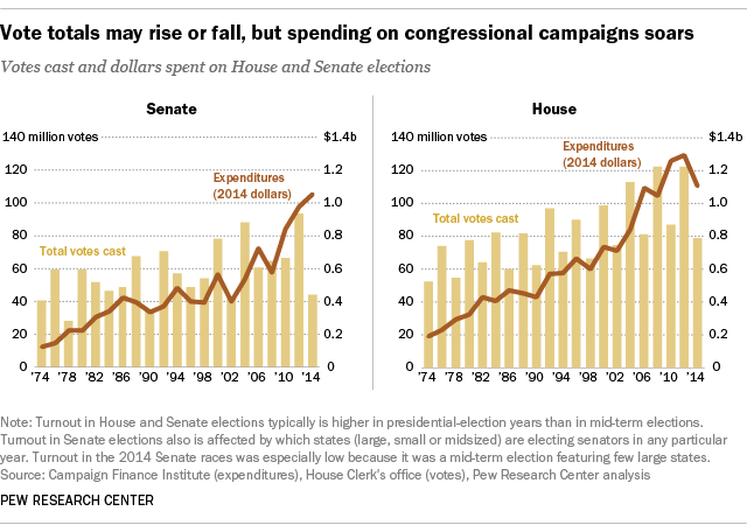

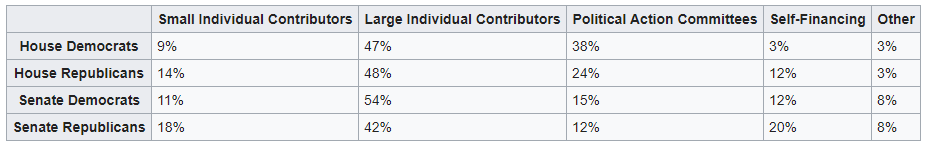

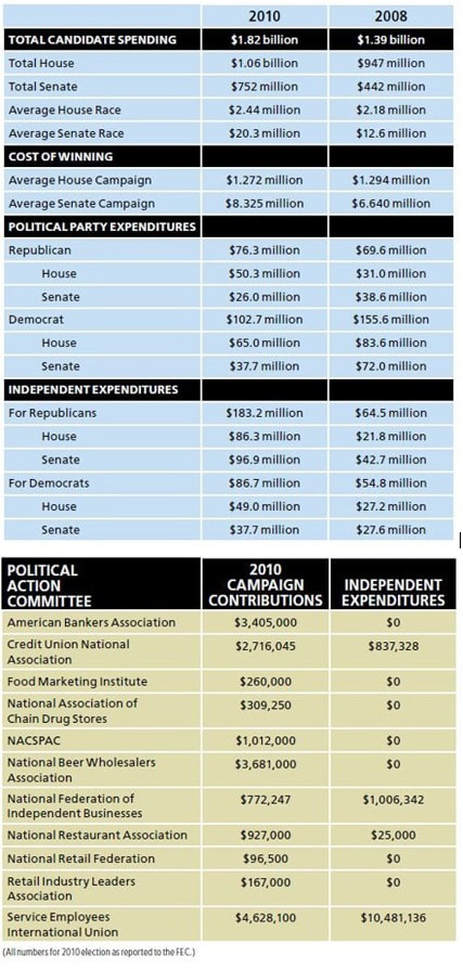

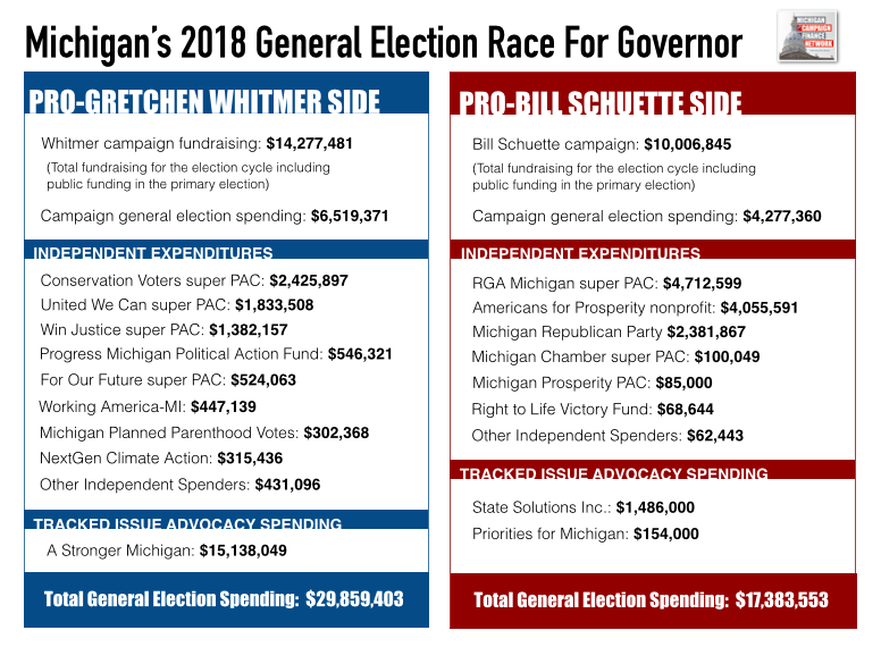

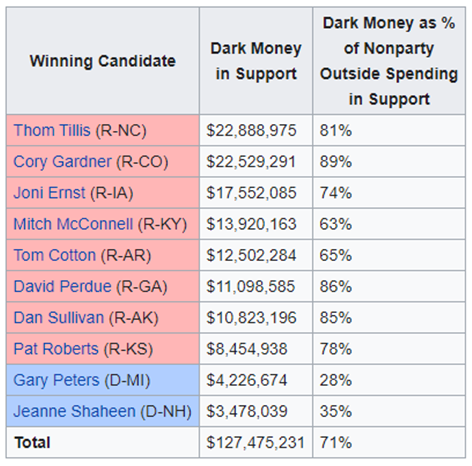

Campaign finance:

Main article: Campaign finance in the United States

Successful participation, especially in federal elections, requires large amounts of money, especially for television advertising. This money is very difficult to raise by appeals to a mass base, although in the 2008 election, candidates from both parties had success with raising money from citizens over the Internet., as had Howard Dean with his Internet appeals.

Both parties generally depend on wealthy donors and organizations - traditionally the Democrats depended on donations from organized labor while the Republicans relied on business donations. Since 1984, however, the Democrats' business donations have surpassed those from labor organizations.

This dependency on donors is controversial, and has led to laws limiting spending on political campaigns being enacted (see campaign finance reform). Opponents of campaign finance laws cite the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech, and challenge campaign finance laws because they attempt to circumvent the people's constitutionally guaranteed rights.

Even when laws are upheld, the complication of compliance with the First Amendment requires careful and cautious drafting of legislation, leading to laws that are still fairly limited in scope, especially in comparison to those of other countries such as the United Kingdom, France or Canada.

Political culture:

Colonial origins:

Main articles: Colonial history of the United States and Thirteen Colonies

The American political culture is deeply rooted in the colonial experience and the American Revolution. The colonies were unique within the European world for their vibrant political culture, which attracted ambitious young men into politics. At the time, American suffrage was the most widespread in the world, with every man who owned a certain amount of property allowed to vote.

Despite this, fewer than 1% of British men could vote, most white American men were eligible. While the roots of democracy were apparent, deference was typically shown to social elites in colonial elections, although this declined sharply with the American Revolution.

In each colony a wide range of public and private business was decided by elected bodies, especially the assemblies and county governments. Topics of public concern and debate included land grants, commercial subsidies, and taxation, as well as the oversight of roads, poor relief, taverns, and schools.

Americans spent a great deal of time in court, as private lawsuits were very common. Legal affairs were overseen by local judges and juries, with a central role for trained lawyers. This promoted the rapid expansion of the legal profession, and dominant role of lawyers in politics was apparent by the 1770s, with notable individuals including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, among many others.

The American colonies were unique in world context because of the growth of representation of different interest groups. Unlike Europe, where the royal court, aristocratic families and the established church were in control, the American political culture was open to merchants, landlords, petty farmers, artisans, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Quakers, Germans, Scotch Irish, Yankees, Yorkers, and many other identifiable groups.

Over 90% of the representatives elected to the legislature lived in their districts, unlike England where it was common to have a member of Parliament and absentee member of Parliament. Finally, and most dramatically, the Americans were fascinated by and increasingly adopted the political values of Republicanism, which stressed equal rights, the need for virtuous citizens, and the evils of corruption, luxury, and aristocracy.

None of the colonies had political parties of the sort that formed in the 1790s, but each had shifting factions that vied for power.

American ideology:

Republicanism, along with a form of classical liberalism remains the dominant ideology. Central documents include the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Constitution (1787), the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (1787-1790s), the Bill of Rights (1791), and Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address" (1863), among others.

Among the core tenets of this ideology are the following:

At the time of the United States' founding, the economy was predominantly one of agriculture and small private businesses, and state governments left welfare issues to private or local initiative. As in the UK and other industrialized countries, laissez-faire ideology was largely discredited during the Great Depression.

Between the 1930s and 1970s, fiscal policy was characterized by the Keynesian consensus, a time during which modern American liberalism dominated economic policy virtually unchallenged. Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, laissez-faire ideology has once more become a powerful force in American politics. While the American welfare state expanded more than threefold after WWII, it has been at 20% of GDP since the late 1970s.

Today, modern American liberalism, and modern American conservatism are engaged in a continuous political battle, characterized by what the Economist describes as "greater divisiveness [and] close, but bitterly fought elections."

Before World War II, the United States pursued a noninterventionist policy of in foreign affairs by not taking sides in conflicts between foreign powers. The country abandoned this policy when it became a superpower, and the country mostly supports internationalism.

Political parties and elections:

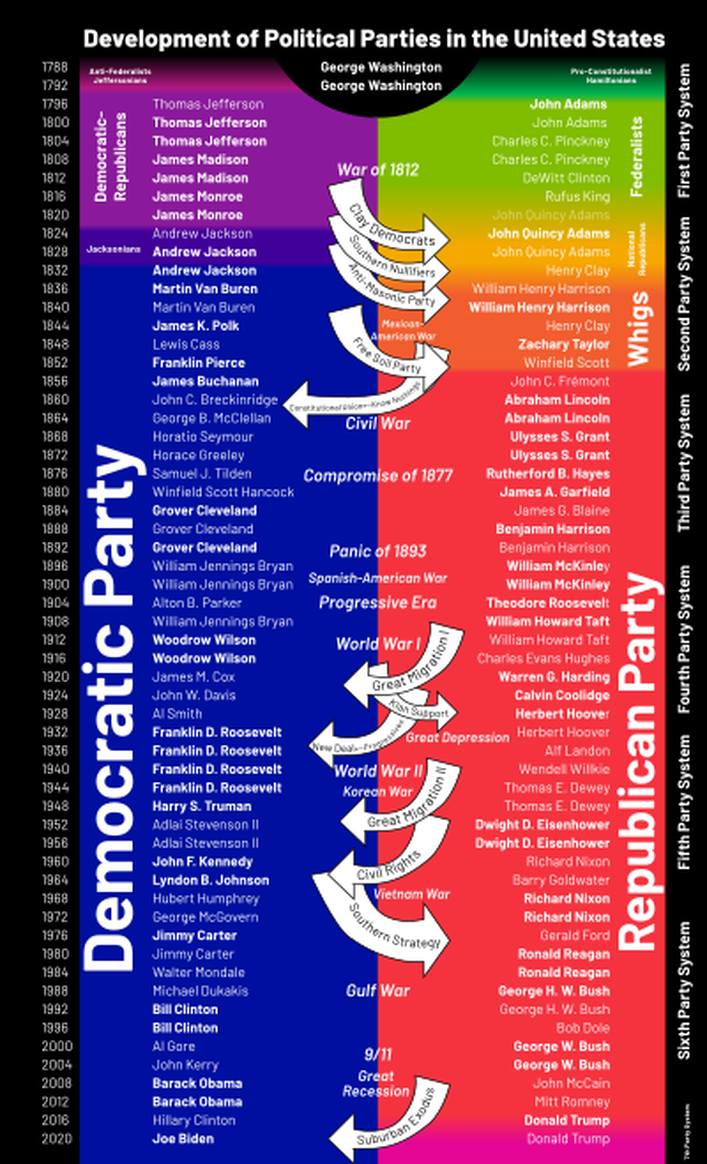

The United States Constitution has never formally addressed the issue of political parties, primarily because the Founding Fathers did not originally intend for American politics to be partisan.

In Federalist Papers No. 9 and No. 10, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, respectively, wrote specifically about the dangers of domestic political factions. In addition, the first President of the United States, George Washington, was not a member of any political party at the time of his election or throughout his tenure as president, and remains to this day the only independent to have held the office. Furthermore, he hoped that political parties would not be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation.

Nevertheless, the beginnings of the American two-party system emerged from his immediate circle of advisers, including Hamilton and Madison.

In partisan elections, candidates are nominated by a political party or seek public office as an independent. Each state has significant discretion in deciding how candidates are nominated, and thus eligible to appear on the election ballot. Typically, major party candidates are formally chosen in a party primary or convention, whereas minor party and Independents are required to complete a petitioning process.

Political parties:

Main article: Political parties in the United States

The modern political party system in the United States is a two-party system dominated by the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. These two parties have won every United States presidential election since 1852 and have controlled the United States Congress since at least 1856. From time to time, several other third parties have achieved relatively minor representation at the national and state levels.

Among the two major parties, the Democratic Party generally positions itself as center-left in American politics and supports an American liberalism platform, while the Republican Party generally positions itself as center-right and supports an American conservatism platform.

Elections:

Further information: Elections in the United States

Unlike the United Kingdom and other similar parliamentary systems, Americans vote for a specific candidate instead of directly selecting a particular political party. With a federal government, officials are elected at the federal (national), state and local levels.

On a national level, the President is elected indirectly by the people, but instead elected through the Electoral College. In modern times, the electors almost always vote with the popular vote of their state, however in rare occurrences they may vote against the popular vote of their state, becoming what is known as a faithless elector. All members of Congress, and the offices at the state and local levels are directly elected.

Both federal and state laws regulate elections.

The United States Constitution defines (to a basic extent) how federal elections are held, in Article One and Article Two and various amendments. State law regulates most aspects of electoral law, including primaries, the eligibility of voters (beyond the basic constitutional definition), the running of each state's electoral college, and the running of state and local elections.

Organization of American political parties:

See also: Political party strength in U.S. states

American political parties are more loosely organized than those in other countries. The two major parties, in particular, have no formal organization at the national level that controls membership. Thus, for an American to say that he or she is a member of the Democratic or Republican parties is quite different from a Briton's stating that he or she is a member of the Conservative or Labor parties.

In most U.S. states, a voter can register as a member of one or another party and/or vote in the primary election for one or another party. A person may choose to attend meetings of one local party committee one day and another party committee the next day.

Party identification becomes somewhat formalized when a person runs for partisan office. In most states, this means declaring oneself a candidate for the nomination of a particular party and intent to enter that party's primary election for an office. A party committee may choose to endorse one or another of those who is seeking the nomination, but in the end the choice is up to those who choose to vote in the primary, and it is often difficult to tell who is going to do the voting.

The result is that American political parties have weak central organizations and little central ideology, except by consensus. A party really cannot prevent a person who disagrees with the majority of positions of the party or actively works against the party's aims from claiming party membership, so long as the voters who choose to vote in the primary elections elect that person. Once in office, an elected official may change parties simply by declaring such intent.

At the federal level, each of the two major parties has a national committee (See, Democratic National Committee, Republican National Committee) that acts as the hub for much fund-raising and campaign activities, particularly in presidential campaigns. The exact composition of these committees is different for each party, but they are made up primarily of representatives from state parties and affiliated organizations, and others important to the party. However, the national committees do not have the power to direct the activities of members of the party.

Both parties also have separate campaign committees which work to elect candidates at a specific level. The most significant of these are the Hill committees, which work to elect candidates to each house of Congress.

State parties exist in all fifty states, though their structures differ according to state law, as well as party rules at both the national and the state level.

Despite these weak organizations, elections are still usually portrayed as national races between the political parties. In what is known as "presidential coattails", candidates in presidential elections become the de facto leader of their respective party, and thus usually bring out supporters who in turn then vote for his party's candidates for other offices.

On the other hand, federal midterm elections (where only Congress and not the president is up for election) are usually regarded as a referendum on the sitting president's performance, with voters either voting in or out the president's party's candidates, which in turn helps the next session of Congress to either pass or block the president's agenda, respectively.

Political pressure groups:

See also: Advocacy group

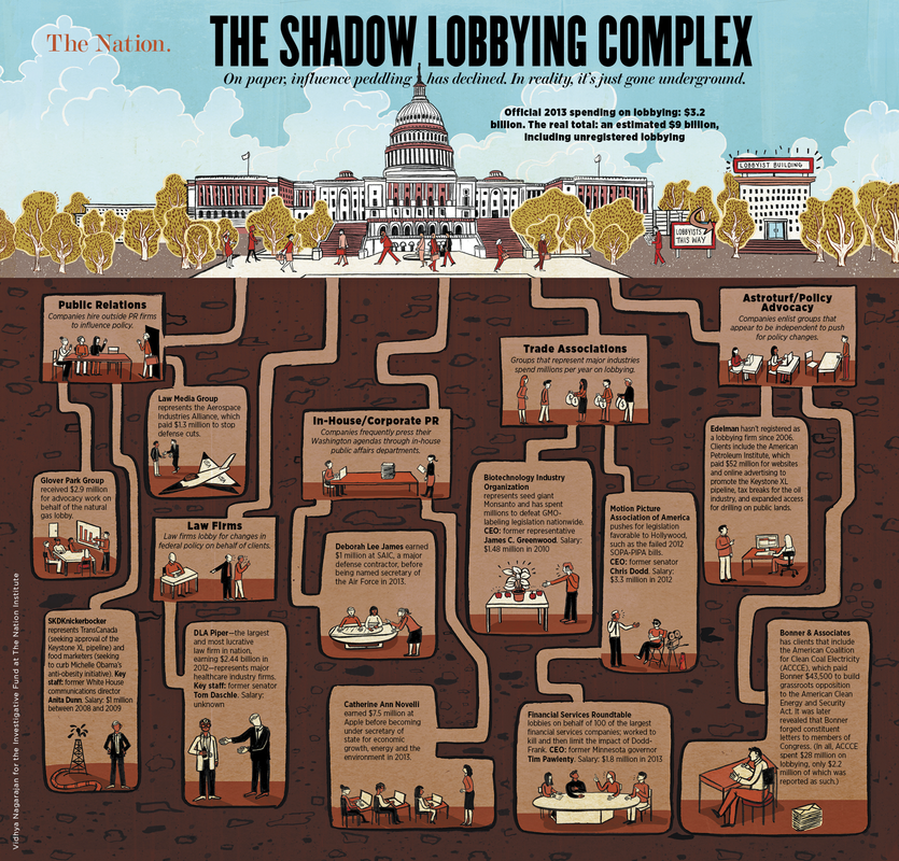

Special interest groups advocate the cause of their specific constituency. Business organizations will favor low corporate taxes and restrictions of the right to strike, whereas labor unions will support minimum wage legislation and protection for collective bargaining.

Other private interest groups, such as churches and ethnic groups, are more concerned about broader issues of policy that can affect their organizations or their beliefs.

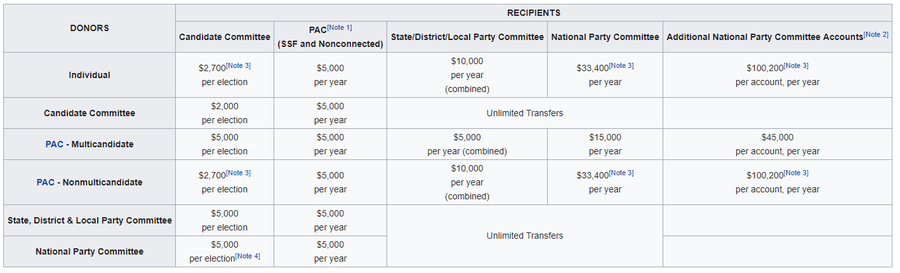

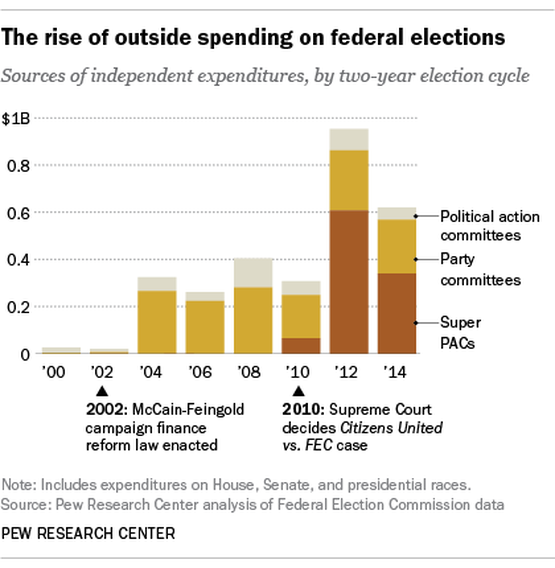

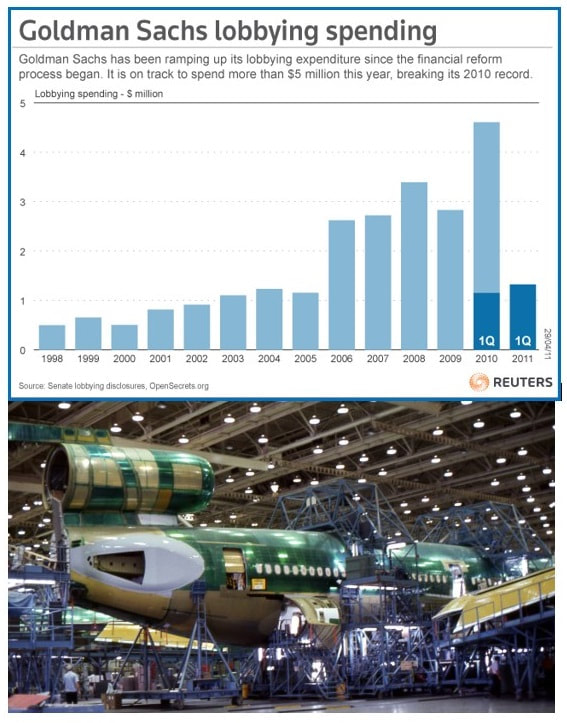

One type of private interest group that has grown in number and influence in recent years is the political action committee or PAC. These are independent groups, organized around a single issue or set of issues, which contribute money to political campaigns for U.S. Congress or the presidency. PACs are limited in the amounts they can contribute directly to candidates in federal elections.

There are no restrictions, however, on the amounts PACs can spend independently to advocate a point of view or to urge the election of candidates to office. PACs today number in the thousands.

"The number of interest groups has mushroomed, with more and more of them operating offices in Washington, D.C., and representing themselves directly to Congress and federal agencies," says Michael Schudson in his 1998 book The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life.

"Many organizations that keep an eye on Washington seek financial and moral support from ordinary citizens. Since many of them focus on a narrow set of concerns or even on a single issue, and often a single issue of enormous emotional weight, they compete with the parties for citizens' dollars, time, and passion."

The amount of money spent by these special interests continues to grow, as campaigns become increasingly expensive. Many Americans have the feeling that these wealthy interests, whether corporations, unions or PACs, are so powerful that ordinary citizens can do little to counteract their influences.

A survey of members of the American Economic Association find the vast majority regardless of political affiliation to be discontent with the current state of democracy in America.

The primary concern relates to the prevalence and influence of special interest groups within the political process, which tends to lead to policy consequences that only benefit such special interest groups and politicians. Some conjecture that maintenance of the policy status quo and hesitance to stray from it perpetuates a political environment that fails to advance society's welfare.

In 2020, political discontent became more prevalent, putting a severe strain on democratic institutions.

General developments:

See also: History of the United States Republican Party;

and History of the United States Democratic Party

Many of America's Founding Fathers hated the thought of political parties. They were sure quarreling factions would be more interested in contending with each other than in working for the common good. They wanted citizens to vote for candidates without the interference of organized groups, but this was not to be.

By the 1790s, different views of the new country's proper course had already developed, and those who held these opposing views tried to win support for their cause by banding together.

The followers of Alexander Hamilton, the Hamiltonian faction, took up the name "Federalist"; they favored a strong central government that would support the interests of commerce and industry.

The followers of Thomas Jefferson, the Jeffersonians and then the "Anti-Federalists," took up the name "Democratic-Republicans"; they preferred a decentralized agrarian republic in which the federal government had limited power.

By 1828, the Federalists had disappeared as an organization, replaced by the Whigs, brought to life in opposition to the election that year of President Andrew Jackson. Jackson's presidency split the Democratic-Republican Party: Jacksonians became the Democratic Party and those following the leadership of John Quincy Adams became the "National Republicans."

The two-party system, still in existence today, was born. (Note: The National Republicans of John Quincy Adams is not the same party as today's Republican Party.)

In the 1850s, the issue of slavery took center stage, with disagreement in particular over the question of whether slavery should be permitted in the country's new territories in the West.

The Whig Party straddled the issue and sank to its death after the overwhelming electoral defeat by Franklin Pierce in the 1852 presidential election.

Ex-Whigs joined the Know Nothings or the newly formed Republican Party. While the Know Nothing party was short-lived, Republicans would survive the intense politics leading up to the Civil War. The primary Republican policy was that slavery be excluded from all the territories.

Just six years later, this new party captured the presidency when Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860. By then, parties were well established as the country's dominant political organizations, and party allegiance had become an important part of most people's consciousness. Party loyalty was passed from fathers to sons, and party activities, including spectacular campaign events, complete with uniformed marching groups and torchlight parades, were a part of the social life of many communities.

By the 1920s, however, this boisterous folksiness had diminished. Municipal reforms, civil service reform, corrupt practices acts, and presidential primaries to replace the power of politicians at national conventions had all helped to clean up politics.

Development of the two-party system in the United States:

See also: Causes of a two-party system

Since the 1790s, the country has been run by two major parties. Many minor or third political parties appear from time to time. They tend to serve a means to advocate policies that eventually are adopted by the two major political parties.

At various times the Socialist Party, the Farmer-Labor Party and the Populist Party for a few years had considerable local strength, and then faded away—although in Minnesota, the Farmer–Labor Party merged into the state's Democratic Party, which is now officially known as the Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party.

At present, the Libertarian Party is the most successful third party. New York State has a number of additional third parties, who sometimes run their own candidates for office and sometimes nominate the nominees of the two main parties. In the District of Columbia, the D.C. Statehood Party has served as a strong third party behind the Democratic Party and Republican Party.

Most officials in America are elected from single-member districts and win office by beating out their opponents in a system for determining winners called first-past-the-post; the one who gets the plurality wins, (which is not the same thing as actually getting a majority of votes). This encourages the two-party system: see Duverger's law.

In the absence of multi-seat congressional districts, proportional representation is impossible and third parties cannot thrive. Senators were originally selected by state legislatures, but have been elected by popular vote since 1913. Although elections to the Senate elect two senators per constituency (state), staggered terms effectively result in single-seat constituencies for elections to the Senate.

Another critical factor has been ballot access law. Originally, voters went to the polls and publicly stated which candidate they supported. Later on, this developed into a process whereby each political party would create its own ballot and thus the voter would put the party's ballot into the voting box.

In the late nineteenth century, states began to adopt the Australian Secret Ballot Method, and it eventually became the national standard. The secret ballot method ensured that the privacy of voters would be protected (hence government jobs could no longer be awarded to loyal voters) and each state would be responsible for creating one official ballot.

The fact that state legislatures were dominated by Democrats and Republicans provided these parties an opportunity to pass discriminatory laws against minor political parties, yet such laws did not start to arise until the first Red Scare that hit America after World War I.

State legislatures began to enact tough laws that made it harder for minor political parties to run candidates for office by requiring a high number of petition signatures from citizens and decreasing the length of time that such a petition could legally be circulated.

It should also be noted that while more often than not, party members will "toe the line" and support their party's policies, they are free to vote against their own party and vote with the opposition ("cross the aisle") when they please.

"In America the same political labels (Democratic and Republican) cover virtually all public officeholders, and therefore most voters are everywhere mobilized in the name of these two parties," says Nelson W. Polsby, professor of political science, in the book New Federalist Papers: Essays in Defense of the Constitution.

"Yet Democrats and Republicans are not everywhere the same. Variations (sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant) in the 50 political cultures of the states yield considerable differences overall in what it means to be, or to vote, Democratic or Republican. These differences suggest that one may be justified in referring to the American two-party system as masking something more like a hundred-party system."

Political spectrum of the two major parties:

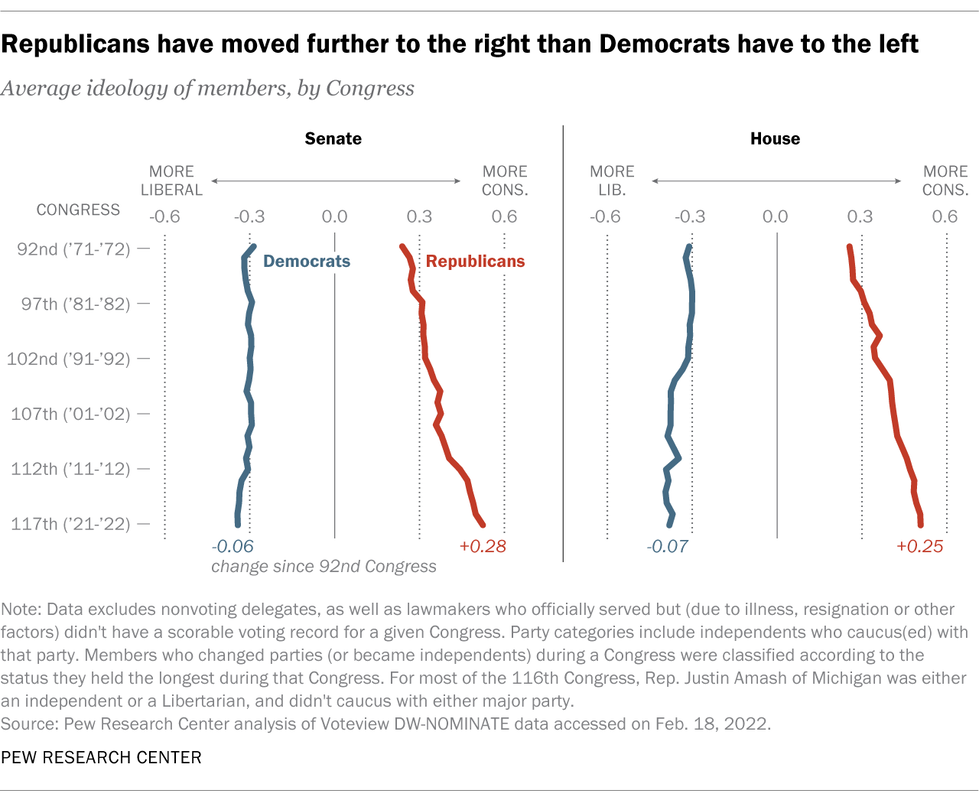

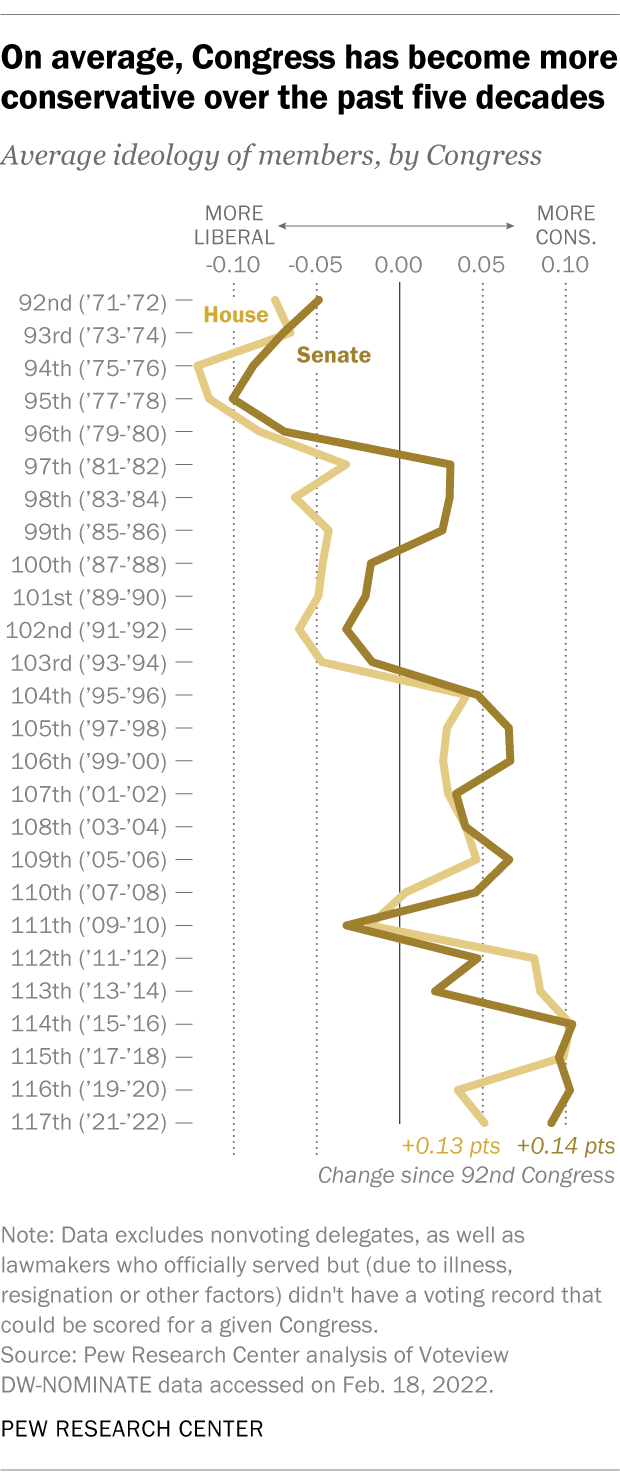

During the 20th century, the overall political philosophy of both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party underwent a dramatic shift from their earlier philosophies.

From the 1860s to the 1950s the Republican Party was considered to be the more classically liberal of the two major parties and the Democratic Party the more classically conservative/populist of the two.

This changed a great deal with the presidency of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal included the founding of Social Security as well as a variety of other federal services and public works projects. Roosevelt's performance in the twin crises of the Depression and World War II led to a sort of polarization in national politics, centered around him; this combined with his increasingly liberal policies to turn FDR's Democrats to the left and the Republican Party further to the right.

During the 1950s and the early 1960s, both parties essentially expressed a more centrist approach to politics on the national level and had their liberal, moderate, and conservative wings influential within both parties.

From the early 1960s, the conservative wing became more dominant in the Republican Party, and the liberal wing became more dominant in the Democratic Party. The 1964 presidential election heralded the rise of the conservative wing among Republicans.

The liberal and conservative wings within the Democratic Party were competitive until 1972, when George McGovern's candidacy marked the triumph of the liberal wing.

This similarly happened in the Republican Party with the candidacy and later landslide election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, which marked the triumph of the conservative wing.

By the 1980 election, each major party had largely become identified by its dominant political orientation. Strong showings in the 1990s by reformist independent Ross Perot pushed the major parties to put forth more centrist presidential candidates, like Bill Clinton and Bob Dole.

Polarization in Congress was said by some to have been cemented by the Republican takeover of 1994. Others say that this polarization had existed since the late 1980s when the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress.

Liberals within the Republican Party and conservatives within the Democratic Party and the Democratic Leadership Council neoliberals have typically fulfilled the roles of so-called political mavericks, radical centrists, or brokers of compromise between the two major parties. They have also helped their respective parties gain in certain regions that might not ordinarily elect a member of that party; the Republican Party has used this approach with centrist Republicans such as Rudy Giuliani, George Pataki, Richard Riordan and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The 2006 elections sent many centrist or conservative Democrats to state and federal legislatures including several, notably in Kansas and Montana, who switched parties.

Concerns about oligarchy:

Some views suggest that the political structure of the United States is in many respects an oligarchy, where a small economic elite overwhelmingly determines policy and law. Some academic researchers suggest a drift toward oligarchy has been occurring by way of the influence of corporations, wealthy, and other special interest groups, leaving individual citizens with less impact than economic elites and organized interest groups in the political process.

A study by political scientists Martin Gilens (Princeton University) and Benjamin Page (Northwestern University) released in April 2014 suggested that when the preferences of a majority of citizens conflicts with elites, elites tend to prevail.

While not characterizing the United States as an "oligarchy" or "plutocracy" outright, Gilens and Page do give weight to the idea of a "civil oligarchy" as used by Jeffrey A. Winters, saying, "Winters has posited a comparative theory of 'Oligarchy,' in which the wealthiest citizens – even in a 'civil oligarchy' like the United States – dominate policy concerning crucial issues of wealth- and income-protection."

In their study, Gilens and Page reached these conclusions:

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman wrote:

The stark reality is that we have a society in which money is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few people. This threatens to make us a democracy in name only.

— Paul Krugman, 2012

For Reform See also:

See also:

It may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and non-violent, or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but also often carries a negative connotation. For example, abolitionist Wendell Phillips declared that "we do not play politics; anti-slavery is no half-jest with us."

The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or limitedly, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it.

A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation with other political subjects, making laws, and exercising force, including warfare against adversaries. Politics is exercised on a wide range of social levels, from clans and tribes of traditional societies, through modern local governments, companies and institutions up to sovereign states, to the international level.

In modern nation states, people often form political parties to represent their ideas. Members of a party often agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support the same changes to law and the same leaders. An election is usually a competition between different parties.

A political system is a framework which defines acceptable political methods within a society. The history of political thought can be traced back to early antiquity, with seminal works such as Plato's Republic, Aristotle's Politics, Chanakya's Arthashastra and Chanakya Niti (3rd century BCE), as well as the works of Confucius.

Etymology:

The English politics has its roots in the name of Aristotle's classic work, Politiká, which introduced the Greek term politiká (Πολιτικά, 'affairs of the cities'). In the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition would be rendered in Early Modern English as Polettiques which would become Politics in Modern English.

The singular politic first attested in English in 1430, coming from Middle French politique—itself taking from politicus, a Latinization of the Greek πολιτικός (politikos) from πολίτης (polites, 'citizen') and πόλις (polis, 'city').

Definitions:

- In the view of Harold Lasswell, politics is "who gets what, when, how."

- For David Easton, it is about "the authoritative allocation of values for a society." To Vladimir Lenin, "politics is the most concentrated expression of economics."

- Bernard Crick argued that "politics is a distinctive form of rule whereby people act together through institutionalized procedures to resolve differences, to conciliate diverse interests and values and to make public policies in the pursuit of common purposes."

- According to Adrian Leftwich: "Politics comprises all the activities of co-operation, negotiation and conflict within and between societies, whereby people go about organizing the use, production or distribution of human, natural and other resources in the course of the production and reproduction of their biological and social life."

Approaches:

There are several ways in which approaching politics has been conceptualized.

Extensive and limited:

Adrian Leftwich has differentiated views of politics based on how extensive or limited their perception of what accounts as 'political' is. The extensive view sees politics as present across the sphere of human social relations, while the limited view restricts it to certain contexts.

For example, in a more restrictive way, politics may be viewed as primarily about governance, while a feminist perspective could argue that sites which have been viewed traditionally as non-political, should indeed be viewed as political as well.

This latter position is encapsulated in the slogan the personal is political, which disputes the distinction between private and public issues. Instead, politics may be defined by the use of power, as has been argued by Robert A. Dahl.

Moralism and realism:

Some perspectives on politics view it empirically as an exercise of power, while other see it as a social function with a normative basis. This distinction has been called the difference between political moralism and political realism.

For moralists, politics is closely linked to ethics, and is at its extreme in utopian thinking. For example, according to Hannah Arendt, the view of Aristotle was that "to be political…meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through violence;" while according to Bernard Crick "[p]olitics is the way in which free societies are governed. Politics is politics and other forms of rule are something else."

In contrast, for realists, represented by those such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Harold Lasswell, politics is based on the use of power, irrespective of the ends being pursued.

Conflict and co-operation:

Agonism argues that politics essentially comes down to conflict between conflicting interests. Political scientist Elmer Schattschneider argued that "at the root of all politics is the universal language of conflict," while for Carl Schmitt the essence of politics is the distinction of 'friend' from foe'.

This is in direct contrast to the more co-operative views of politics by Aristotle and Crick. However, a more mixed view between these extremes is provided by Irish author Michael Laver, who noted that: Politics is about the characteristic blend of conflict and co-operation that can be found so often in human interactions. Pure conflict is war. Pure co-operation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.

Political science:

Main article: Political science

The study of politics is called political science, or politology. It comprises numerous subfields, including:

- comparative politics,

- political economy,

- international relations,

- political philosophy,

- public administration,

- public policy,

- and political methodology.

Furthermore, political science is related to, and draws upon, the fields of

- economics,

- law,

- sociology,

- history,

- philosophy,

- geography,

- psychology/psychiatry,

- anthropology,

- and neurosciences.

Comparative politics is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields, all of them from an intrastate perspective.

International relations deals with the interaction between nation-states as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations. Political philosophy is more concerned with contributions of various classical and contemporary thinkers and philosophers.

Political science is methodologically diverse and appropriates many methods originating in psychology, social research, and cognitive neuroscience.

Approaches include

- positivism,

- interpretivism,

- rational choice theory,

- behavioralism,

- structuralism,

- post-structuralism,

- realism,

- institutionalism,

- and pluralism.

Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, experimental research, and model building.

Political system:

Main article: Political system

See also: Systems theory in political science

The political system defines the process for making official government decisions. It is usually compared to the legal system, economic system, cultural system, and other social systems.

According to David Easton, "A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society." Each political system is embedded in a society with its own political culture, and they in turn shape their societies through public policy. The interactions between different political systems are the basis for global politics.

Forms of government:

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and republics (usually presidential, semi-presidential, or parliamentary).

The separation of powers describes the degree of horizontal integration between the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, and other independent institutions.

Source of power:

The source of power determines the difference between democracies, oligarchies, and autocracies.

In a democracy, political legitimacy is based on popular sovereignty. Forms of democracy include representative democracy, direct democracy, and demarchy. These are separated by the way decisions are made, whether by elected representatives, referenda, or by citizen juries.

Democracies can be either republics or constitutional monarchies.

Oligarchy is a power structure where a minority rules. These may be in the form of:

- anocracy,

- aristocracy,

- ergatocracy,

- geniocracy,

- gerontocracy,

- kakistocracy,

- kleptocracy,

- meritocracy,

- noocracy,

- particracy,

- plutocracy,

- stratocracy,

- technocracy,

- theocracy,

- or timocracy.

Autocracies are either dictatorships (including military dictatorships) or absolute monarchies.

Vertical integration: In terms of level of vertical integration, political systems can be divided into (from least to most integrated) confederations, federations, and unitary states.

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism).

In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body.

Federations were formed first in Switzerland, then in the United States in 1776, in Canada in 1867 and in Germany in 1871 and in 1901, Australia. Compared to a federation, a confederation has less centralized power.

State:

All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic polity, the sovereign state. The state has been defined by Max Weber as a political entity that has monopoly on violence within its territory, while the Montevideo Convention holds that states need to have a defined territory; a permanent population; a government; and a capacity to enter into international relations.

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small. Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.

While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state.

In some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.

Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved. A central tenet of anarchism is the advocacy of society without states. The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought, ranging from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.

In Marxism, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and wither away. A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society.

Constitutions:

Constitutions are written documents that specify and limit the powers of the different branches of government. Although a constitution is a written document, there is also an unwritten constitution.

The unwritten constitution is continually being written by the legislative and judiciary branch of government; this is just one of those cases in which the nature of the circumstances determines the form of government that is most appropriate.