Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

This Page covers

Finance

including Financial Markets,

Instruments, Corporate, Personal,

Public, Banks and Banking, Regulation,

and Standards.

Finance

including Financial Markets,

Instruments, Corporate, Personal,

Public, Banks and Banking, Regulation,

and Standards.

Finance, including An Outline of Finance and a List of Financial Categories

YouTube Video: "Stock market for beginners" - Advice by Warren Buffet*

* - Warren Buffet

Click here for a List of Financial Categories.

Finance is a field that deals with the study of investments. It includes the dynamics of assets and liabilities over time under conditions of different degrees of uncertainty and risk. Finance can also be defined as the science of money management. Finance aims to price assets based on their risk level and their expected rate of return. Finance can be broken into three sub-categories: public finance, corporate finance and personal finance.

Personal finance:

Main article: Personal finance

Questions in personal finance revolve around:

Personal finance may involve paying for education, financing durable goods such as real estate and cars, buying insurance, e.g. health and property insurance, investing and saving for retirement.

Personal finance may also involve paying for a loan, or debt obligations. The six key areas of personal financial planning, as suggested by the Financial Planning Standards Board, are:

Corporate finance:

Main article: Corporate finance

Corporate finance deals with the sources funding and the capital structure of corporations, the actions that managers take to increase the value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and analysis used to allocate financial resources. Although it is in principle different from managerial finance which studies the financial management of all firms, rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms.

Corporate finance generally involves balancing risk and profitability, while attempting to maximize an entity's assets, net incoming cash flow and the value of its stock, and generically entails three primary areas of capital resource allocation. In the first, "capital budgeting", management must choose which "projects" (if any) to undertake.

The discipline of capital budgeting may employ standard business valuation techniques or even extend to real options valuation; see Financial modeling.

The second, "sources of capital" relates to how these investments are to be funded: investment capital can be provided through different sources, such as by shareholders, in the form of equity (privately or via an initial public offering), creditors, often in the form of bonds, and the firm's operations (cash flow). Short-term funding or working capital is mostly provided by banks extending a line of credit. The balance between these elements forms the company's capital structure.

The third, "the dividend policy", requires management to determine whether any unappropriated profit (excess cash) is to be retained for future investment / operational requirements, or instead to be distributed to shareholders, and if so, in what form. Short term financial management is often termed "working capital management", and relates to cash-, inventory- and debtors management.

Corporate finance also includes within its scope business valuation, stock investing, or investment management. An investment is an acquisition of an asset in the hope that it will maintain or increase its value over time that will in hope give back a higher rate of return when it comes to disbursing dividends.

In investment management – in choosing a portfolio – one has to use financial analysis to determine what, how much and when to invest. To do this, a company must:

Financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession.

However, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, while financial management is concerned with the allocation of capital resources to increase a firm's value to the shareholders and increase their rate of return on the investments.

Financial risk management, an element of corporate finance, is the practice of creating and protecting economic value in a firm by using financial instruments to manage exposure to risk, particularly credit risk and market risk. (Other risk types include foreign exchange, shape, volatility, sector, liquidity, inflation risks, etc.) It focuses on when and how to hedge using financial instruments; in this sense it overlaps with financial engineering.

Similar to general risk management, financial risk management requires identifying its sources, measuring it (see: Risk measure#Examples), and formulating plans to address these, and can be qualitative and quantitative. In the banking sector worldwide, the Basel Accords are generally adopted by internationally active banks for tracking, reporting and exposing operational, credit and market risks.

Financial services:

Main article: Financial services

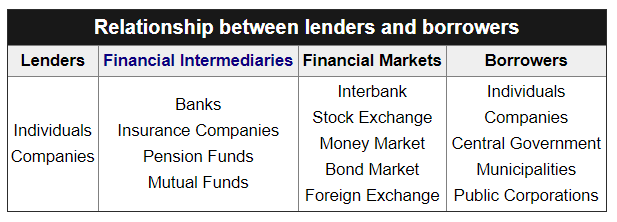

An entity whose income exceeds its expenditure can lend or invest the excess income to help that excess income produce more income in the future. Though on the other hand, an entity whose income is less than its expenditure can raise capital by borrowing or selling equity claims, decreasing its expenses, or increasing its income.

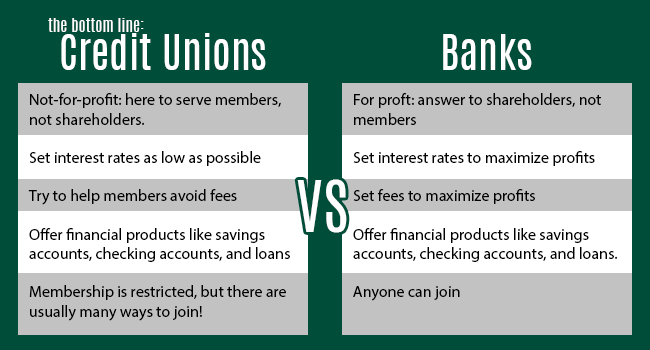

The lender can find a borrower—a financial intermediary such as a bank—or buy notes or bonds (corporate bonds, government bonds, or mutual bonds) in the bond market. The lender receives interest, the borrower pays a higher interest than the lender receives, and the financial intermediary earns the difference for arranging the loan.

A bank aggregates the activities of many borrowers and lenders. A bank accepts deposits from lenders, on which it pays interest. The bank then lends these deposits to borrowers.

Banks allow borrowers and lenders, of different sizes, to coordinate their activity.

Finance is used by individuals (personal finance), by governments (public finance), by businesses (corporate finance) and by a wide variety of other organizations such as schools and non-profit organizations. In general, the goals of each of the above activities are achieved through the use of appropriate financial instruments and methodologies, with consideration to their institutional setting.

Finance is one of the most important aspects of business management and includes analysis related to the use and acquisition of funds for the enterprise.

In corporate finance, a company's capital structure is the total mix of financing methods it uses to raise funds. One method is debt financing, which includes bank loans and bond sales.

Another method is equity financing – the sale of stock by a company to investors, the original shareholders (they own a portion of the business) of a share.

Ownership of a share gives the shareholder certain contractual rights and powers, which typically include the right to receive declared dividends and to vote the proxy on important matters (e.g., board elections).

The owners of both bonds (either government bonds or corporate bonds) and stock (whether its preferred stock or common stock), may be institutional investors – financial institutions such as investment banks and pension funds or private individuals, called private investors or retail investors.

Public finance:

Main article: Public finance

Public finance describes finance as related to sovereign states and sub-national entities (states/provinces, counties, municipalities, etc.) and related public entities (e.g. school districts) or agencies. It usually encompasses a long-term strategic perspective regarding investment decisions that affect public entities. These long-term strategic periods usually encompass five or more years. Public finance is primarily concerned with:

Capital:

Main article: Financial capital

Capital, in the financial sense, is the money that gives the business the power to buy goods to be used in the production of other goods or the offering of a service. (Capital has two types of sources, equity and debt).

The deployment of capital is decided by the budget. This may include the objective of business, targets set, and results in financial terms, e.g., the target set for sale, resulting cost, growth, required investment to achieve the planned sales, and financing source for the investment.

A budget may be long term or short term. Long term budgets have a time horizon of 5–10 years giving a vision to the company; short term is an annual budget which is drawn to control and operate in that particular year.

Budgets will include proposed fixed asset requirements and how these expenditures will be financed. Capital budgets are often adjusted annually (done every year) and should be part of a longer-term Capital Improvements Plan.

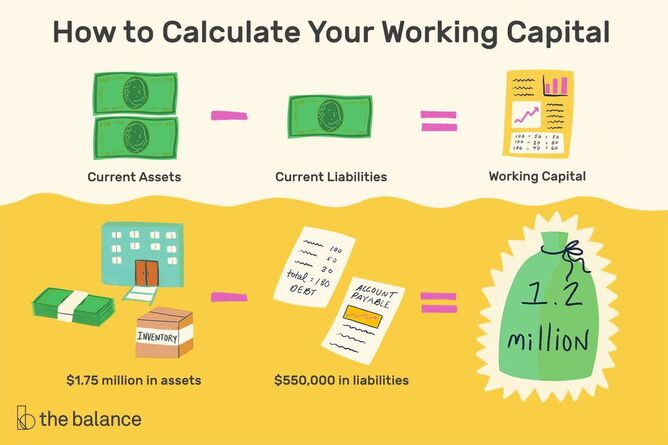

A cash budget is also required. The working capital requirements of a business are monitored at all times to ensure that there are sufficient funds available to meet short-term expenses.

The cash budget is basically a detailed plan that shows all expected sources and uses of cash when it comes to spending it appropriately. The cash budget has the following six main sections:

Financial Theory:

Financial economics:

Main article: Financial economics

Financial economics is the branch of economics studying the interrelation of financial variables, such as prices, interest rates and shares, as opposed to goods and services.

Financial economics concentrates on influences of real economic variables on financial ones, in contrast to pure finance. It centres on managing risk in the context of the financial markets, and the resultant economic and financial models. It essentially explores how rational investors would apply risk and return to the problem of an investment policy.

Here, the twin assumptions of rationality and market efficiency lead to modern portfolio theory (the CAPM), and to the Black–Scholes theory for option valuation; it further studies phenomena and models where these assumptions do not hold, or are extended. "Financial economics", at least formally, also considers investment under "certainty" (Fisher separation theorem, "theory of investment value", Modigliani–Miller theorem) and hence also contributes to corporate finance theory.

Financial econometrics is the branch of financial economics that uses econometric techniques to parameterize the relationships suggested.

Although closely related, the disciplines of economics and finance are distinct. The “economy” is a social institution that organizes a society’s production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, all of which must be financed.

Financial mathematics:

Main article: Financial mathematics

Financial mathematics is a field of applied mathematics, concerned with financial markets. The subject has a close relationship with the discipline of financial economics, which is concerned with much of the underlying theory that is involved in financial mathematics.

Generally, mathematical finance will derive, and extend, the mathematical or numerical models suggested by financial economics. In terms of practice, mathematical finance also overlaps heavily with the field of computational finance (also known as financial engineering).

Arguably, these are largely synonymous, although the latter focuses on application, while the former focuses on modelling and derivation (see: Quantitative analyst). The field is largely focused on the modelling of derivatives, although other important sub-fields include insurance mathematics and quantitative portfolio problems. See later herein for "Outline of finance: Mathematical tools" and "Outline of finance: Derivatives pricing".

Experimental finance:

Main article: Experimental finance

Experimental finance aims to establish different market settings and environments to observe experimentally and provide a lens through which science can analyze agents' behavior and the resulting characteristics of trading flows, information diffusion and aggregation, price setting mechanisms, and returns processes.

Researchers in experimental finance can study to what extent existing financial economics theory makes valid predictions and therefore prove them, and attempt to discover new principles on which such theory can be extended and be applied to future financial decisions.

Research may proceed by conducting trading simulations or by establishing and studying the behavior, and the way that these people act or react, of people in artificial competitive market-like settings.

Behavioral finance:

Main article: Behavioral economics

Behavioral finance studies how the psychology of investors or managers affects financial decisions and markets when making a decision that can impact either negatively or positively on one of their areas. Behavioral finance has grown over the last few decades to become central and very important to finance.

Behavioral finance includes such topics as:

A strand of behavioral finance has been dubbed quantitative behavioral finance, which uses mathematical and statistical methodology to understand behavioral biases in conjunction with valuation.

Some of these endeavors has been led by Gunduz Caginalp (Professor of Mathematics and Editor of Journal of Behavioral Finance during 2001-2004) and collaborators including Vernon Smith (2002 Nobel Laureate in Economics), David Porter, Don Balenovich, Vladimira Ilieva, Ahmet Duran). Studies by Jeff Madura, Ray Sturm and others have demonstrated significant behavioral effects in stocks and exchange traded funds.

Among other topics, quantitative behavioral finance studies behavioral effects together with the non-classical assumption of the finiteness of assets.

Professional Qualifications: Click Here.

Unsolved Problems in Finance:

As the debate to whether finance is an art or a science is still open, there have been recent efforts to organize a list of unsolved problems in finance.

See Also:

Outline of Finance:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to finance:

Finance – addresses the ways in which individuals and organizations raise and allocate monetary resources over time, taking into account the risks entailed in their projects.

The word finance may incorporate any of the following:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Outline of Finance:

Finance is a field that deals with the study of investments. It includes the dynamics of assets and liabilities over time under conditions of different degrees of uncertainty and risk. Finance can also be defined as the science of money management. Finance aims to price assets based on their risk level and their expected rate of return. Finance can be broken into three sub-categories: public finance, corporate finance and personal finance.

Personal finance:

Main article: Personal finance

Questions in personal finance revolve around:

- Protection against unforeseen personal events, as well as events in the wider economies

- Transference of family wealth across generations (bequests and inheritance)

- Effects of tax policies (tax subsidies or penalties) management of personal finances

- Effects of credit on individual financial standing

- Development of a savings plan or financing for large purchases (auto, education, home)

- Planning a secure financial future in an environment of economic instability

Personal finance may involve paying for education, financing durable goods such as real estate and cars, buying insurance, e.g. health and property insurance, investing and saving for retirement.

Personal finance may also involve paying for a loan, or debt obligations. The six key areas of personal financial planning, as suggested by the Financial Planning Standards Board, are:

- Financial position: is concerned with understanding the personal resources available by examining net worth and household cash flows. Net worth is a person's balance sheet, calculated by adding up all assets under that person's control, minus all liabilities of the household, at one point in time. Household cash flows total up all from the expected sources of income within a year, minus all expected expenses within the same year. From this analysis, the financial planner can determine to what degree and in what time the personal goals can be accomplished.

- Adequate protection: the analysis of how to protect a household from unforeseen risks. These risks can be divided into the following: liability, property, death, disability, health and long term care. Some of these risks may be self-insurable, while most will require the purchase of an insurance contract. Determining how much insurance to get, at the most cost effective terms requires knowledge of the market for personal insurance. Business owners, professionals, athletes and entertainers require specialized insurance professionals to adequately protect themselves. Since insurance also enjoys some tax benefits, utilizing insurance investment products may be a critical piece of the overall investment planning.

- Tax planning: typically the income tax is the single largest expense in a household. Managing taxes is not a question of if you will pay taxes, but when and how much. Government gives many incentives in the form of tax deductions and credits, which can be used to reduce the lifetime tax burden. Most modern governments use a progressive tax. Typically, as one's income grows, a higher marginal rate of tax must be paid. Understanding how to take advantage of the myriad tax breaks when planning one's personal finances can make a significant impact in which it can later save you money in the long term.

- Investment and accumulation goals: planning how to accumulate enough money – for large purchases and life events – is what most people consider to be financial planning. Major reasons to accumulate assets include purchasing a house or car, starting a business, paying for education expenses, and saving for retirement. Achieving these goals requires projecting what they will cost, and when you need to withdraw funds that will be necessary to be able to achieve these goals. A major risk to the household in achieving their accumulation goal is the rate of price increases over time, or inflation. Using net present value calculators, the financial planner will suggest a combination of asset earmarking and regular savings to be invested in a variety of investments. In order to overcome the rate of inflation, the investment portfolio has to get a higher rate of return, which typically will subject the portfolio to a number of risks. Managing these portfolio risks is most often accomplished using asset allocation, which seeks to diversify investment risk and opportunity. This asset allocation will prescribe a percentage allocation to be invested in stocks (either preferred stock or common stock), bonds (for example mutual bonds or government bonds, or corporate bonds), cash and alternative investments. The allocation should also take into consideration the personal risk profile of every investor, since risk attitudes vary from person to person.

- Retirement planning is the process of understanding how much it costs to live at retirement, and coming up with a plan to distribute assets to meet any income shortfall. Methods for retirement plan include taking advantage of government allowed structures to manage tax liability including: individual (IRA) structures, or employer sponsored retirement plans.

- Estate planning involves planning for the disposition of one's assets after death. Typically, there is a tax due to the state or federal government at one's death. Avoiding these taxes means that more of one's assets will be distributed to one's heirs. One can leave one's assets to family, friends or charitable groups.

Corporate finance:

Main article: Corporate finance

Corporate finance deals with the sources funding and the capital structure of corporations, the actions that managers take to increase the value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and analysis used to allocate financial resources. Although it is in principle different from managerial finance which studies the financial management of all firms, rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms.

Corporate finance generally involves balancing risk and profitability, while attempting to maximize an entity's assets, net incoming cash flow and the value of its stock, and generically entails three primary areas of capital resource allocation. In the first, "capital budgeting", management must choose which "projects" (if any) to undertake.

The discipline of capital budgeting may employ standard business valuation techniques or even extend to real options valuation; see Financial modeling.

The second, "sources of capital" relates to how these investments are to be funded: investment capital can be provided through different sources, such as by shareholders, in the form of equity (privately or via an initial public offering), creditors, often in the form of bonds, and the firm's operations (cash flow). Short-term funding or working capital is mostly provided by banks extending a line of credit. The balance between these elements forms the company's capital structure.

The third, "the dividend policy", requires management to determine whether any unappropriated profit (excess cash) is to be retained for future investment / operational requirements, or instead to be distributed to shareholders, and if so, in what form. Short term financial management is often termed "working capital management", and relates to cash-, inventory- and debtors management.

Corporate finance also includes within its scope business valuation, stock investing, or investment management. An investment is an acquisition of an asset in the hope that it will maintain or increase its value over time that will in hope give back a higher rate of return when it comes to disbursing dividends.

In investment management – in choosing a portfolio – one has to use financial analysis to determine what, how much and when to invest. To do this, a company must:

- Identify relevant objectives and constraints: institution or individual goals, time horizon, risk aversion and tax considerations;

- Identify the appropriate strategy: active versus passive hedging strategy

- Measure the portfolio performance

Financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession.

However, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, while financial management is concerned with the allocation of capital resources to increase a firm's value to the shareholders and increase their rate of return on the investments.

Financial risk management, an element of corporate finance, is the practice of creating and protecting economic value in a firm by using financial instruments to manage exposure to risk, particularly credit risk and market risk. (Other risk types include foreign exchange, shape, volatility, sector, liquidity, inflation risks, etc.) It focuses on when and how to hedge using financial instruments; in this sense it overlaps with financial engineering.

Similar to general risk management, financial risk management requires identifying its sources, measuring it (see: Risk measure#Examples), and formulating plans to address these, and can be qualitative and quantitative. In the banking sector worldwide, the Basel Accords are generally adopted by internationally active banks for tracking, reporting and exposing operational, credit and market risks.

Financial services:

Main article: Financial services

An entity whose income exceeds its expenditure can lend or invest the excess income to help that excess income produce more income in the future. Though on the other hand, an entity whose income is less than its expenditure can raise capital by borrowing or selling equity claims, decreasing its expenses, or increasing its income.

The lender can find a borrower—a financial intermediary such as a bank—or buy notes or bonds (corporate bonds, government bonds, or mutual bonds) in the bond market. The lender receives interest, the borrower pays a higher interest than the lender receives, and the financial intermediary earns the difference for arranging the loan.

A bank aggregates the activities of many borrowers and lenders. A bank accepts deposits from lenders, on which it pays interest. The bank then lends these deposits to borrowers.

Banks allow borrowers and lenders, of different sizes, to coordinate their activity.

Finance is used by individuals (personal finance), by governments (public finance), by businesses (corporate finance) and by a wide variety of other organizations such as schools and non-profit organizations. In general, the goals of each of the above activities are achieved through the use of appropriate financial instruments and methodologies, with consideration to their institutional setting.

Finance is one of the most important aspects of business management and includes analysis related to the use and acquisition of funds for the enterprise.

In corporate finance, a company's capital structure is the total mix of financing methods it uses to raise funds. One method is debt financing, which includes bank loans and bond sales.

Another method is equity financing – the sale of stock by a company to investors, the original shareholders (they own a portion of the business) of a share.

Ownership of a share gives the shareholder certain contractual rights and powers, which typically include the right to receive declared dividends and to vote the proxy on important matters (e.g., board elections).

The owners of both bonds (either government bonds or corporate bonds) and stock (whether its preferred stock or common stock), may be institutional investors – financial institutions such as investment banks and pension funds or private individuals, called private investors or retail investors.

Public finance:

Main article: Public finance

Public finance describes finance as related to sovereign states and sub-national entities (states/provinces, counties, municipalities, etc.) and related public entities (e.g. school districts) or agencies. It usually encompasses a long-term strategic perspective regarding investment decisions that affect public entities. These long-term strategic periods usually encompass five or more years. Public finance is primarily concerned with:

- Identification of required expenditure of a public sector entity

- Source(s) of that entity's revenue

- The budgeting process

- Debt issuance (municipal bonds) for public works projects

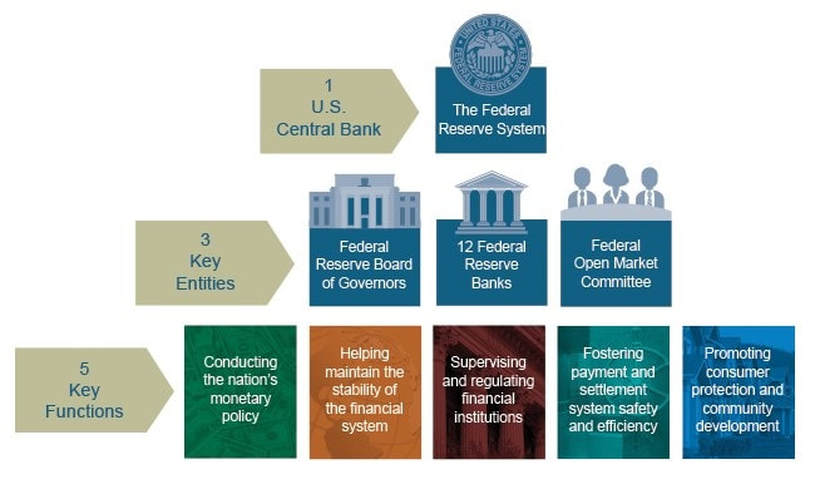

- Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve System banks in the United States and Bank of England in the United Kingdom, are strong players in public finance, acting as lenders of last resort as well as strong influences on monetary and credit conditions in the economy.

Capital:

Main article: Financial capital

Capital, in the financial sense, is the money that gives the business the power to buy goods to be used in the production of other goods or the offering of a service. (Capital has two types of sources, equity and debt).

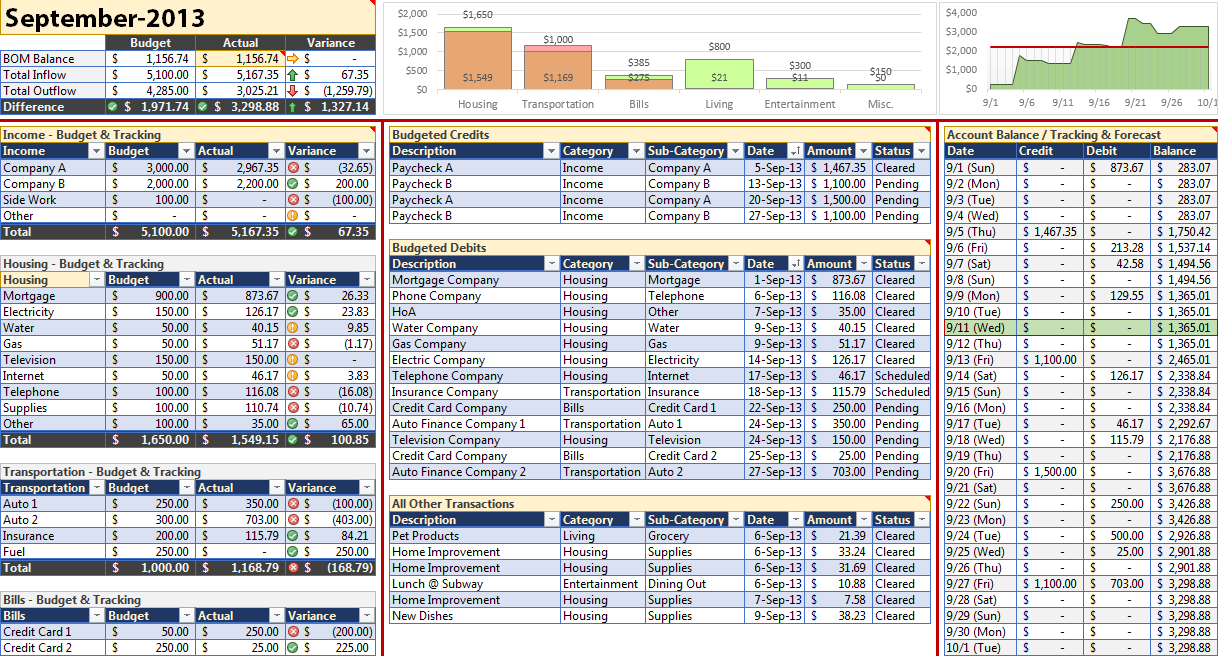

The deployment of capital is decided by the budget. This may include the objective of business, targets set, and results in financial terms, e.g., the target set for sale, resulting cost, growth, required investment to achieve the planned sales, and financing source for the investment.

A budget may be long term or short term. Long term budgets have a time horizon of 5–10 years giving a vision to the company; short term is an annual budget which is drawn to control and operate in that particular year.

Budgets will include proposed fixed asset requirements and how these expenditures will be financed. Capital budgets are often adjusted annually (done every year) and should be part of a longer-term Capital Improvements Plan.

A cash budget is also required. The working capital requirements of a business are monitored at all times to ensure that there are sufficient funds available to meet short-term expenses.

The cash budget is basically a detailed plan that shows all expected sources and uses of cash when it comes to spending it appropriately. The cash budget has the following six main sections:

- Beginning cash balance – contains the last period's closing cash balance, in other words, the remaining cash of the last year.

- Cash collections – includes all expected cash receipts (all sources of cash for the period considered, mainly sales)

- Cash disbursements – lists all planned cash outflows for the period such as dividend, excluding interest payments on short-term loans, which appear in the financing section. All expenses that do not affect cash flow are excluded from this list (e.g. depreciation, amortization, etc.)

- Cash excess or deficiency – a function of the cash needs and cash available. Cash needs are determined by the total cash disbursements plus the minimum cash balance required by company policy. If total cash available is less than cash needs, a deficiency exists.

- Financing – discloses the planned borrowings and repayments of those planned borrowings, including interest.

Financial Theory:

Financial economics:

Main article: Financial economics

Financial economics is the branch of economics studying the interrelation of financial variables, such as prices, interest rates and shares, as opposed to goods and services.

Financial economics concentrates on influences of real economic variables on financial ones, in contrast to pure finance. It centres on managing risk in the context of the financial markets, and the resultant economic and financial models. It essentially explores how rational investors would apply risk and return to the problem of an investment policy.

Here, the twin assumptions of rationality and market efficiency lead to modern portfolio theory (the CAPM), and to the Black–Scholes theory for option valuation; it further studies phenomena and models where these assumptions do not hold, or are extended. "Financial economics", at least formally, also considers investment under "certainty" (Fisher separation theorem, "theory of investment value", Modigliani–Miller theorem) and hence also contributes to corporate finance theory.

Financial econometrics is the branch of financial economics that uses econometric techniques to parameterize the relationships suggested.

Although closely related, the disciplines of economics and finance are distinct. The “economy” is a social institution that organizes a society’s production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, all of which must be financed.

Financial mathematics:

Main article: Financial mathematics

Financial mathematics is a field of applied mathematics, concerned with financial markets. The subject has a close relationship with the discipline of financial economics, which is concerned with much of the underlying theory that is involved in financial mathematics.

Generally, mathematical finance will derive, and extend, the mathematical or numerical models suggested by financial economics. In terms of practice, mathematical finance also overlaps heavily with the field of computational finance (also known as financial engineering).

Arguably, these are largely synonymous, although the latter focuses on application, while the former focuses on modelling and derivation (see: Quantitative analyst). The field is largely focused on the modelling of derivatives, although other important sub-fields include insurance mathematics and quantitative portfolio problems. See later herein for "Outline of finance: Mathematical tools" and "Outline of finance: Derivatives pricing".

Experimental finance:

Main article: Experimental finance

Experimental finance aims to establish different market settings and environments to observe experimentally and provide a lens through which science can analyze agents' behavior and the resulting characteristics of trading flows, information diffusion and aggregation, price setting mechanisms, and returns processes.

Researchers in experimental finance can study to what extent existing financial economics theory makes valid predictions and therefore prove them, and attempt to discover new principles on which such theory can be extended and be applied to future financial decisions.

Research may proceed by conducting trading simulations or by establishing and studying the behavior, and the way that these people act or react, of people in artificial competitive market-like settings.

Behavioral finance:

Main article: Behavioral economics

Behavioral finance studies how the psychology of investors or managers affects financial decisions and markets when making a decision that can impact either negatively or positively on one of their areas. Behavioral finance has grown over the last few decades to become central and very important to finance.

Behavioral finance includes such topics as:

- Empirical studies that demonstrate significant deviations from classical theories.

- Models of how psychology affects and impacts trading and prices

- Forecasting based on these methods.

- Studies of experimental asset markets and use of models to forecast experiments.

A strand of behavioral finance has been dubbed quantitative behavioral finance, which uses mathematical and statistical methodology to understand behavioral biases in conjunction with valuation.

Some of these endeavors has been led by Gunduz Caginalp (Professor of Mathematics and Editor of Journal of Behavioral Finance during 2001-2004) and collaborators including Vernon Smith (2002 Nobel Laureate in Economics), David Porter, Don Balenovich, Vladimira Ilieva, Ahmet Duran). Studies by Jeff Madura, Ray Sturm and others have demonstrated significant behavioral effects in stocks and exchange traded funds.

Among other topics, quantitative behavioral finance studies behavioral effects together with the non-classical assumption of the finiteness of assets.

Professional Qualifications: Click Here.

Unsolved Problems in Finance:

As the debate to whether finance is an art or a science is still open, there have been recent efforts to organize a list of unsolved problems in finance.

See Also:

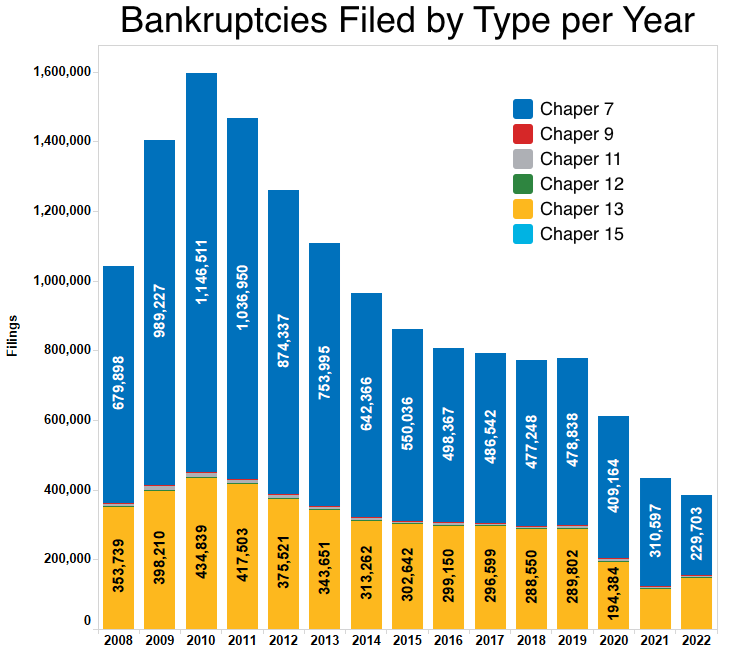

- Financial crisis of 2007–2010

- List of unsolved problems in finance

- Learn Finance Step by step with infographics tools

- OECD work on financial markets Observation of UK Finance Market

- Wharton Finance Knowledge Project – aimed to offer free access to finance knowledge for students, teachers, and self-learners.

- Professor Aswath Damodaran (New York University Stern School of Business) – provides resources covering three areas in finance: corporate finance, valuation and investment management and syndicate finance.

Outline of Finance:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to finance:

Finance – addresses the ways in which individuals and organizations raise and allocate monetary resources over time, taking into account the risks entailed in their projects.

The word finance may incorporate any of the following:

- The study of money and other assets

- The management and control of those assets

- Profiling and managing project risks

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Outline of Finance:

- Fundamental financial concepts

- History

- Finance terms by field

- Financial markets

- Financial regulation

- Actuarial topics

- Asset types

- Raising capital

- Valuation

- Financial software tools

- Financial institutions

- Lists:

- See also:

- Actuarial topics

- Wharton Finance Knowledge Project – aimed to offer free access to finance knowledge for students, teachers, and self-learners.

- Comprehensive site about topics of financial theory, with a focus in Corporate Finance, Valuation and Investments. Updated Data, Excel Spreadsheets and more. Prof. Aswath Damodaran

- For links to finance web sites, grouped by topic see Web Sites for Discerning Finance Students, Prof. John M. Wachowicz -

- For the introductory finance web site at the University of Arizona, studyfinance.com

- For introductory articles, a full glossary and links to resources on behavioral finance see the BF gallery

- For the law of the financial markets see SECLaw.com

- For various shared blog posts on finance see fwisp.com

- For stock market related financial definitions see TheStreet.com Glossary

- The Finance Director provides access to essential suppliers of financial services and solutions

Financial Management

YouTube Video: Financial Planning 101 Introduction

Financial management refers to the efficient and effective management of money (funds) in such a manner as to accomplish the objectives of the organization. It is the specialized function directly associated with the top management. The significance of this function is not seen in the 'Line' but also in the capacity of 'Staff' in overall of a company. It has been defined differently by different experts in the field.

The term typically applies to an organization or company's financial strategy, while personal finance or financial life management refers to an individual's management strategy. It includes how to raise the capital and how to allocate capital, i.e. capital budgeting. Not only for long term budgeting, but also how to allocate the short term resources like current liabilities. It also deals with the dividend policies of the share holders.

Definitions:

Objectives:

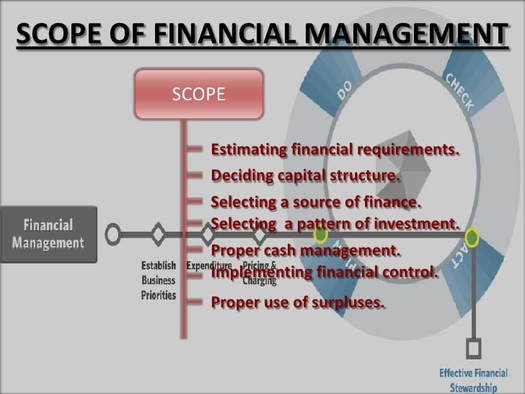

Scope:

Financial Management for Startups:

For new enterprises, it is important to make a good estimation on costs, sales. Consideration on appropriate length sources of finances can help businesses avoid the cash flow problems even the failure of setting up. There are fixed and current sides of assets balance sheet:

See also:

The term typically applies to an organization or company's financial strategy, while personal finance or financial life management refers to an individual's management strategy. It includes how to raise the capital and how to allocate capital, i.e. capital budgeting. Not only for long term budgeting, but also how to allocate the short term resources like current liabilities. It also deals with the dividend policies of the share holders.

Definitions:

- "Planning is an inextricable dimension of financial management. The term financial management connotes that funds flows are directed according to some plan." By James Van Horne

- "Financial management is that activity of management which is concerned with the planning, procuring and controlling of the firm's financial resources. " By Deepika &Maya Rani

- “Financial Management is the Operational Activity of a business that is responsible for obtaining and effectively utilizing the funds necessary for efficient operation.” By Joseph Massie

- “Business finance deals primarily with rising administering and disbursing funds by privately owned business units operating in non-financial fields of industry.”– By Kuldeep Roy

- “Financial Management is an area of financial decision making, harmonizing individual motives and enterprise goals." -By Weston and Brigham

- “Financial management is the area of business management devoted to a judicious use of capital and a careful selection of sources of capital in order to enable a business firm to move in the direction of reaching its goals.” – by J.F.Bradlery

- “Financial management is the application of the planning and control function to the finance function.” – by K.D. Willson

- “Financial management may be defined as that area or set of administrative function in an organization which relate with arrangement of cash and credit so that organization may have the means to carry out its objective as satisfactorily as possible." - by Howard & Opton.

- Business finance can be broadly defined as the activity concerned with planning, raising, controlling and administering of funds and in the business. “ by H.G Gathman & H.E Dougall

- Financial management is a body of business concerned with the efficient and effective use of either equity capital, borrowed cash or any other business funds as well as taking the right decision for profit maximization and value addition of an entity.- Kepher Petra; Kisii University.

- "Financial management refers to the proper and efficient use of money and it plays a significant role in analyzing to invest in profitable business enterprise. Return on Investment must be greater than the invested amount."

- "Financial management refers to the effective and efficient management of money and it is also process of planning, controlling,leading, directing of a firm's financial resources."

Objectives:

- Profit maximization happens when marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue. This is the main objective of Financial Management.

- Wealth maximization means maximization of shareholders' wealth. It is an advanced goal compared to profit maximization.

- Survival of company is an important consideration when the financial manager makes any financial decisions. One incorrect decision may lead company to be bankrupt.

- Maintaining proper cash flow is a short run objective of financial management. It is necessary for operations to pay the day-to-day expenses e.g. raw material, electricity bills, wages, rent etc. A good cash flow ensures the survival of company.

- Minimization on capital cost in financial management can help operations gain more profit.

- It is vague :- There are several types of profits before interest, depreciation and taxes,profit before taxes , profit after taxes , cash profit etc

Scope:

- Estimating the Requirement of Funds: Businesses make forecast on funds needed in both short run and long run, hence, they can improve the efficiency of funding. The estimation is based on the budget e.g. sales budget, production budget.

- Determining the Capital Structure: Capital structure is how a firm finances its overall operations and growth by using different sources of funds. Once the requirement of funds has estimated, the financial manager should decide the mix of debt and equity and also types of debt.

- Investment Fund: A good investment plan can bring businesses huge returns.

Financial Management for Startups:

For new enterprises, it is important to make a good estimation on costs, sales. Consideration on appropriate length sources of finances can help businesses avoid the cash flow problems even the failure of setting up. There are fixed and current sides of assets balance sheet:

- Fixed assets refers to assets that cannot be converted into cash easily, like plant, property, equipment etc.

- A current asset is an item on an entity's balance sheet that is either cash, a cash equivalent, or which can be converted into cash within one year. It is not easy for start ups to forecast the current asset, because there are changes in receivables and payables.

See also:

- Managerial finance, a branch of finance concerned with the managerial significance of financial techniques.

- Corporate finance, a branch of finance concerned with monetary resource allocations made by corporations

- Financial management for IT services, financial management of IT assets and resources

- Financial Planning Association, an organization for finance and economics students and professionals

- Financial Management Service, a bureau of the U.S. Treasury which provides financial services for the government.

- Financial planner

Corporate Finance

YouTube Video: Corporate Finance Explained in LESS than 3 minutes

Corporate finance is the area of finance dealing with the sources of funding and the capital structure of corporations, the actions that managers take to increase the value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and analysis used to allocate financial resources.

The primary goal of corporate finance is to maximize or increase shareholder value. Although it is in principle different from managerial finance which studies the financial management of all firms, rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms.

Correspondingly, corporate finance comprises two main sub-disciplines:

The terms corporate finance and corporate financier are also associated with investment banking. The typical role of an investment bank is to evaluate the company's financial needs and raise the appropriate type of capital that best fits those needs. Thus, the terms "corporate finance" and "corporate financier" may be associated with transactions in which capital is raised in order to create, develop, grow or acquire businesses.

Recent legal and regulatory developments in the U.S. will likely alter the makeup of the group of arrangers and financiers willing to arrange and provide financing for certain highly leveraged transactions.

Financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession. However, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, while financial management is concerned with the allocation of capital resources to increase a firm's value to the shareholders.

Outline:

The primary goal of financial management is to maximize or to continually increase shareholder value. Maximizing shareholder value requires managers to be able to balance capital funding between investments in projects that increase the firm's long term profitability and sustainability, along with paying excess cash in the form of dividends to shareholders.

Managers of growth companies (i.e. firms that earn high rates of return on invested capital) will use most of the firm's capital resources and surplus cash on investments and projects so the company can continue to expand its business operations into the future. When companies reach maturity levels within their industry (i.e. companies that earn approximately average or lower returns on invested capital), managers of these companies will use surplus cash to payout dividends to shareholders.

Managers must do an analysis to determine the appropriate allocation of the firm's capital resources and cash surplus between projects and payouts of dividends to shareholders, as well as paying back creditor related debt.

Choosing between investment projects will be based upon several inter-related criteria:

This "capital budgeting" is the planning of value-adding, long-term corporate financial projects relating to investments funded through and affecting the firm's capital structure. Management must allocate the firm's limited resources between competing opportunities (projects).

Capital budgeting is also concerned with the setting of criteria about which projects should receive investment funding to increase the value of the firm, and whether to finance that investment with equity or debt capital.

Investments should be made on the basis of value-added to the future of the corporation. Projects that increase a firm's value may include a wide variety of different types of investments, including but not limited to, expansion policies, or mergers and acquisitions.

When no growth or expansion is possible by a corporation and excess cash surplus exists and is not needed, then management is expected to pay out some or all of those surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends or to repurchase the company's stock through a share buyback program.

Capital Structure:

Capitalization:

Main article: Capital structure

Further information: Security (finance)

Achieving the goals of corporate finance requires that any corporate investment be financed appropriately. The sources of financing are, generically, capital self-generated by the firm and capital from external funders, obtained by issuing new debt and equity (and hybrid- or convertible securities).

As above, since both hurdle rate and cash flows (and hence the riskiness of the firm) will be affected, the financing mix will impact the valuation of the firm. There are two interrelated considerations here:

Much of the theory here, falls under the umbrella of the Trade-Off Theory in which firms are assumed to trade-off the tax benefits of debt with the bankruptcy costs of debt when choosing how to allocate the company's resources. However economists have developed a set of alternative theories about how managers allocate a corporation's finances.

One of the main alternative theories of how firms manage their capital funds is the Pecking Order Theory (Stewart Myers), which suggests that firms avoid external financing while they have internal financing available and avoid new equity financing while they can engage in new debt financing at reasonably low interest rates.

Also, Capital structure substitution theory hypothesizes that management manipulates the capital structure such that earnings per share (EPS) are maximized. An emerging area in finance theory is right-financing whereby investment banks and corporations can enhance investment return and company value over time by determining the right investment objectives, policy framework, institutional structure, source of financing (debt or equity) and expenditure framework within a given economy and under given market conditions.

One of the more recent innovations in this area from a theoretical point of view is the Market timing hypothesis. This hypothesis, inspired in the behavioral finance literature, states that firms look for the cheaper type of financing regardless of their current levels of internal resources, debt and equity.

Sources of capital:

Further information: Security (finance)

Debt capital:

Further information: Bankruptcy and Financial distress

Corporations may rely on borrowed funds (debt capital or credit) as sources of investment to sustain ongoing business operations or to fund future growth. Debt comes in several forms, such as through bank loans, notes payable, or bonds issued to the public.

Bonds require the corporations to make regular interest payments (interest expenses) on the borrowed capital until the debt reaches its maturity date, therein the firm must pay back the obligation in full.

Debt payments can also be made in the form of sinking fund provisions, whereby the corporation pays annual installments of the borrowed debt above regular interest charges.

Corporations that issue callable bonds are entitled to pay back the obligation in full whenever the company feels it is in their best interest to pay off the debt payments. If interest expenses cannot be made by the corporation through cash payments, the firm may also use collateral assets as a form of repaying their debt obligations (or through the process of liquidation).

Equity capital:

Corporations can alternatively sell shares of the company to investors to raise capital. Investors, or shareholders, expect that there will be an upward trend in value of the company (or appreciate in value) over time to make their investment a profitable purchase. Shareholder value is increased when corporations invest equity capital and other funds into projects (or investments) that earn a positive rate of return for the owners.

Investors prefer to buy shares of stock in companies that will consistently earn a positive rate of return on capital in the future, thus increasing the market value of the stock of that corporation. Shareholder value may also be increased when corporations payout excess cash surplus (funds from retained earnings that are not needed for business) in the form of dividends.

Preferred stock:

Preferred stock is an equity security which may have any combination of features not possessed by common stock including properties of both an equity and a debt instrument, and is generally considered a hybrid instrument. Preferreds are senior (i.e. higher ranking) to common stock, but subordinate to bonds in terms of claim (or rights to their share of the assets of the company).

Preferred stock usually carries no voting rights, but may carry a dividend and may have priority over common stock in the payment of dividends and upon liquidation. Terms of the preferred stock are stated in a "Certificate of Designation".

Similar to bonds, preferred stocks are rated by the major credit-rating companies. The rating for preferreds is generally lower, since preferred dividends do not carry the same guarantees as interest payments from bonds and they are junior to all creditors.

Preferred stock is a special class of shares which may have any combination of features not possessed by common stock. The following features are usually associated with preferred stock:

Investment and project valuation:

Further information: Business valuation, stock valuation, and fundamental analysis

In general, each project's value will be estimated using a discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation, and the opportunity with the highest value, as measured by the resultant net present value (NPV) will be selected (applied to Corporate Finance by Joel Dean in 1951).

This requires estimating the size and timing of all of the incremental cash flows resulting from the project. Such future cash flows are then discounted to determine their present value (see Time value of money). These present values are then summed, and this sum net of the initial investment outlay is the NPV. See Financial modeling.

The NPV is greatly affected by the discount rate. Thus, identifying the proper discount rate – often termed, the project "hurdle rate" – is critical to choosing good projects and investments for the firm. The hurdle rate is the minimum acceptable return on an investment – i.e., the project appropriate discount rate. The hurdle rate should reflect the riskiness of the investment, typically measured by volatility of cash flows, and must take into account the project-relevant financing mix.

Managers use models such as the CAPM or the APT to estimate a discount rate appropriate for a particular project, and use the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to reflect the financing mix selected. (A common error in choosing a discount rate for a project is to apply a WACC that applies to the entire firm. Such an approach may not be appropriate where the risk of a particular project differs markedly from that of the firm's existing portfolio of assets.)

In conjunction with NPV, there are several other measures used as (secondary) selection criteria in corporate finance. These are visible from the DCF and include the following:

Alternatives (complements) to NPV include the following:

See list of valuation topics.

Valuing flexibility:

Main articles: Real options analysis and decision tree

In many cases, for example R&D projects, a project may open (or close) various paths of action to the company, but this reality will not (typically) be captured in a strict NPV approach.

Some analysts account for this uncertainty by adjusting the discount rate (e.g. by increasing the cost of capital) or the cash flows (using certainty equivalents, or applying (subjective) "haircuts" to the forecast numbers).

Even when employed, however, these latter methods do not normally properly account for changes in risk over the project's lifecycle and hence fail to appropriately adapt the risk adjustment. Management will therefore (sometimes) employ tools which place an explicit value on these options.

So, whereas in a DCF valuation the most likely or average or scenario specific cash flows are discounted, here the "flexible and staged nature" of the investment is modelled, and hence "all" potential payoffs are considered. See further under Real options valuation. The difference between the two valuations is the "value of flexibility" inherent in the project.

The two most common tools are Decision Tree Analysis (DTA) and Real options valuation (ROV); they may often be used interchangeably:

DTA values flexibility by incorporating possible events (or states) and consequent management decisions. (For example, a company would build a factory given that demand for its product exceeded a certain level during the pilot-phase, and outsource production otherwise.

In turn, given further demand, it would similarly expand the factory, and maintain it otherwise. In a DCF model, by contrast, there is no "branching" – each scenario must be modeled separately.) In the decision tree, each management decision in response to an "event" generates a "branch" or "path" which the company could follow; the probabilities of each event are determined or specified by management.

Once the tree is constructed: (1) "all" possible events and their resultant paths are visible to management; (2) given this "knowledge" of the events that could follow, and assuming rational decision making, management chooses the branches (i.e. actions) corresponding to the highest value path probability weighted; (3) this path is then taken as representative of project value. See Decision theory#Choice under uncertainty.

ROV is usually used when the value of a project is contingent on the value of some other asset or underlying variable. (For example, the viability of a mining project is contingent on the price of gold; if the price is too low, management will abandon the mining rights, if sufficiently high, management will develop the ore body.

Again, a DCF valuation would capture only one of these outcomes:

(1) using financial option theory as a framework, the decision to be taken is identified as corresponding to either a call option or a put option;

(2) an appropriate valuation technique is then employed – usually a variant on the Binomial options model or a bespoke simulation model, while Black Scholes type formulae are used less often; see Contingent claim valuation.

(3) The "true" value of the project is then the NPV of the "most likely" scenario plus the option value. (Real options in corporate finance were first discussed by Stewart Myers in 1977; viewing corporate strategy as a series of options was originally per Timothy Luehrman, in the late 1990s.) See also Option pricing approaches under Business valuation.

Quantifying uncertainty:

Further information: Sensitivity analysis, Scenario planning, and Monte Carlo methods in finance.

Given the uncertainty inherent in project forecasting and valuation, analysts will wish to assess the sensitivity of project NPV to the various inputs (i.e. assumptions) to the DCF model.

In a typical sensitivity analysis the analyst will vary one key factor while holding all other inputs constant, ceteris paribus. The sensitivity of NPV to a change in that factor is then observed, and is calculated as a "slope": ΔNPV / Δfactor.

For example, the analyst will determine NPV at various growth rates in annual revenue as specified (usually at set increments, e.g. -10%, -5%, 0%, 5%....), and then determine the sensitivity using this formula.

Often, several variables may be of interest, and their various combinations produce a "value-surface", (or even a "value-space",) where NPV is then a function of several variables. See also Stress testing.

Using a related technique, analysts also run scenario based forecasts of NPV. Here, a scenario comprises a particular outcome for economy-wide, "global" factors (demand for the product, exchange rates, commodity prices, etc...) as well as for company-specific factors (unit costs, etc...).

As an example, the analyst may specify various revenue growth scenarios (e.g. 0% for "Worst Case", 10% for "Likely Case" and 20% for "Best Case"), where all key inputs are adjusted so as to be consistent with the growth assumptions, and calculate the NPV for each.

Note that for scenario based analysis, the various combinations of inputs must be internally consistent (see discussion at Financial modeling), whereas for the sensitivity approach these need not be so.

An application of this methodology is to determine an "unbiased" NPV, where management determines a (subjective) probability for each scenario – the NPV for the project is then the probability-weighted average of the various scenarios; see First Chicago Method. (See also rNPV, where cash flows, as opposed to scenarios, are probability-weighted.)

A further advancement which "overcomes the limitations of sensitivity and scenario analyses by examining the effects of all possible combinations of variables and their realizations" is to construct stochastic or probabilistic financial models – as opposed to the traditional static and deterministic models as above.

For this purpose, the most common method is to use Monte Carlo simulation to analyze the project's NPV. This method was introduced to finance by David B. Hertz in 1964, although it has only recently become common: today analysts are even able to run simulations in spreadsheet based DCF models, typically using a risk-analysis add-in, such as @Risk or Crystal Ball. Here, the cash flow components that are (heavily) impacted by uncertainty are simulated, mathematically reflecting their "random characteristics".

In contrast to the scenario approach above, the simulation produces several thousand random but possible outcomes, or trials, "covering all conceivable real world contingencies in proportion to their likelihood;" see Monte Carlo Simulation versus "What If" Scenarios.

The output is then a histogram of project NPV, and the average NPV of the potential investment – as well as its volatility and other sensitivities – is then observed. This histogram provides information not visible from the static DCF: for example, it allows for an estimate of the probability that a project has a net present value greater than zero (or any other value).

Continuing the above example: instead of assigning three discrete values to revenue growth, and to the other relevant variables, the analyst would assign an appropriate probability distribution to each variable (commonly triangular or beta), and, where possible, specify the observed or supposed correlation between the variables. These distributions would then be "sampled" repeatedly – incorporating this correlation – so as to generate several thousand random but possible scenarios, with corresponding valuations, which are then used to generate the NPV histogram.

The resultant statistics (average NPV and standard deviation of NPV) will be a more accurate mirror of the project's "randomness" than the variance observed under the scenario based approach. These are often used as estimates of the underlying "spot price" and volatility for the real option valuation as above; see Real options valuation: Valuation inputs. A more robust Monte Carlo model would include the possible occurrence of risk events (e.g., a credit crunch) that drive variations in one or more of the DCF model inputs.

Dividend Policy:

Main article: Dividend policy

Dividend policy is concerned with financial policies regarding the payment of a cash dividend in the present or paying an increased dividend at a later stage. Whether to issue dividends, and what amount, is determined mainly on the basis of the company's unappropriated profit (excess cash) and influenced by the company's long-term earning power.

When cash surplus exists and is not needed by the firm, then management is expected to pay out some or all of those surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends or to repurchase the company's stock through a share buyback program.

If there are no NPV positive opportunities, i.e. projects where returns exceed the hurdle rate, and excess cash surplus is not needed, then – finance theory suggests – management should return some or all of the excess cash to shareholders as dividends. This is the general case, however there are exceptions.

For example, shareholders of a "growth stock", expect that the company will, almost by definition, retain most of the excess cash surplus so as to fund future projects internally to help increase the value of the firm.

Management must also choose the form of the dividend distribution, generally as cash dividends or via a share buyback. Various factors may be taken into consideration: where shareholders must pay tax on dividends, firms may elect to retain earnings or to perform a stock buyback, in both cases increasing the value of shares outstanding.

Alternatively, some companies will pay "dividends" from stock rather than in cash; see Corporate action. Financial theory suggests that the dividend policy should be set based upon the type of company and what management determines is the best use of those dividend resources for the firm to its shareholders.

As a general rule, shareholders of growth companies would prefer managers to retain earnings and pay no dividends (use excess cash to reinvest into the company's operations), whereas shareholders of value or secondary stocks would prefer the management of these companies to payout surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends when a positive return cannot be earned through the reinvestment of undistributed earnings.

A share buyback program may be accepted when the value of the stock is greater than the returns to be realized from the reinvestment of undistributed profits. In all instances, the appropriate dividend policy is usually directed by that which maximizes long-term shareholder value.

Working Capital Management:

Main article: Working capital

Managing the corporation's working capital position to sustain ongoing business operations is referred to as working capital management. These involve managing the relationship between a firm's short-term assets and its short-term liabilities.

In general this is as follows: As above, the goal of Corporate Finance is the maximization of firm value. In the context of long term, capital budgeting, firm value is enhanced through appropriately selecting and funding NPV positive investments.

These investments, in turn, have implications in terms of cash flow and cost of capital. The goal of Working Capital (i.e. short term) management is therefore to ensure that the firm is able to operate, and that it has sufficient cash flow to service long-term debt, and to satisfy both maturing short-term debt and upcoming operational expenses. In so doing, firm value is enhanced when, and if, the return on capital exceeds the cost of capital; See Economic value added (EVA). Managing short term finance and long term finance is one task of a modern CFO.

Working capital:

Working capital is the amount of funds which are necessary to an organization to continue its ongoing business operations, until the firm is reimbursed through payments for the goods or services it has delivered to its customers.

Working capital is measured through the difference between resources in cash or readily convertible into cash (Current Assets), and cash requirements (Current Liabilities). As a result, capital resource allocations relating to working capital are always current, i.e. short-term.

In addition to time horizon, working capital management differs from capital budgeting in terms of discounting and profitability considerations; they are also "reversible" to some extent. (Considerations as to Risk appetite and return targets remain identical, although some constraints – such as those imposed by loan covenants – may be more relevant here).

The (short term) goals of working capital are therefore not approached on the same basis as (long term) profitability, and working capital management applies different criteria in allocating resources: the main considerations are (1) cash flow / liquidity and (2) profitability / return on capital (of which cash flow is probably the most important).

Management of working capital:

Guided by the above criteria, management will use a combination of policies and techniques for the management of working capital. These policies aim at managing the current assets (generally cash and cash equivalents, inventories and debtors) and the short term financing, such that cash flows and returns are acceptable:

Relationship with other areas in finance:

Investment banking:

Use of the term "corporate finance" varies considerably across the world. In the United States it is used, as above, to describe activities, analytical methods and techniques that deal with many aspects of a company's finances and capital. In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries, the terms "corporate finance" and "corporate financier" tend to be associated with investment banking – i.e. with transactions in which capital is raised for the corporation. These may include

Financial risk management:

Main article: Financial risk management

See also:

Risk management is the process of measuring risk and then developing and implementing strategies to manage ("hedge") that risk. Financial risk management, typically, is focused on the impact on corporate value due to adverse changes in commodity prices, interest rates, foreign exchange rates and stock prices (market risk).

Risk Management will also play an important role in short term cash- and treasury management; see above. It is common for large corporations to have risk management teams; often these overlap with the internal audit function. While it is impractical for small firms to have a formal risk management function, many still apply risk management informally. See also Enterprise risk management.

The discipline typically focuses on risks that can be hedged using traded financial instruments, typically derivatives.

See also:

Because company specific, "over the counter" (OTC) contracts tend to be costly to create and monitor, derivatives that trade on well-established financial markets or exchanges are often preferred. These standard derivative instruments include the following:

The "second generation" exotic derivatives usually trade OTC. Note that hedging-related transactions will attract their own accounting treatment: see Hedge accounting, Mark-to-market accounting, FASB 133, IAS 39.

This area is related to corporate finance in two ways. Firstly, firm exposure to business and market risk is a direct result of previous capital financial investments. Secondly, both disciplines share the goal of enhancing, or preserving, firm value.

There is a fundamental debate relating to "Risk Management" and shareholder value.

Per the Modigliani and Miller framework, hedging is irrelevant since diversified shareholders are assumed to not care about firm-specific risks, whereas, on the other hand hedging is seen to create value in that it reduces the probability of financial distress.

A further question, is the shareholder's desire to optimize risk versus taking exposure to pure risk (a risk event that only has a negative side, such as loss of life or limb). The debate links the value of risk management in a market to the cost of bankruptcy in that market.

See also:

The primary goal of corporate finance is to maximize or increase shareholder value. Although it is in principle different from managerial finance which studies the financial management of all firms, rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms.

Correspondingly, corporate finance comprises two main sub-disciplines:

- Capital budgeting is concerned with the setting of criteria about which value-adding projects should receive investment funding, and whether to finance that investment with equity or debt capital.

- Working capital management is the management of the company's monetary funds that deal with the short-term operating balance of current assets and current liabilities; the focus here is on managing cash, inventories, and short-term borrowing and lending (such as the terms on credit extended to customers).

The terms corporate finance and corporate financier are also associated with investment banking. The typical role of an investment bank is to evaluate the company's financial needs and raise the appropriate type of capital that best fits those needs. Thus, the terms "corporate finance" and "corporate financier" may be associated with transactions in which capital is raised in order to create, develop, grow or acquire businesses.

Recent legal and regulatory developments in the U.S. will likely alter the makeup of the group of arrangers and financiers willing to arrange and provide financing for certain highly leveraged transactions.

Financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession. However, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, while financial management is concerned with the allocation of capital resources to increase a firm's value to the shareholders.

Outline:

The primary goal of financial management is to maximize or to continually increase shareholder value. Maximizing shareholder value requires managers to be able to balance capital funding between investments in projects that increase the firm's long term profitability and sustainability, along with paying excess cash in the form of dividends to shareholders.

Managers of growth companies (i.e. firms that earn high rates of return on invested capital) will use most of the firm's capital resources and surplus cash on investments and projects so the company can continue to expand its business operations into the future. When companies reach maturity levels within their industry (i.e. companies that earn approximately average or lower returns on invested capital), managers of these companies will use surplus cash to payout dividends to shareholders.

Managers must do an analysis to determine the appropriate allocation of the firm's capital resources and cash surplus between projects and payouts of dividends to shareholders, as well as paying back creditor related debt.

Choosing between investment projects will be based upon several inter-related criteria:

- Corporate management seeks to maximize the value of the firm by investing in projects which yield a positive net present value when valued using an appropriate discount rate in consideration of risk.

- These projects must also be financed appropriately.

- If no growth is possible by the company and excess cash surplus is not needed to the firm, then financial theory suggests that management should return some or all of the excess cash to shareholders (i.e., distribution via dividends).

This "capital budgeting" is the planning of value-adding, long-term corporate financial projects relating to investments funded through and affecting the firm's capital structure. Management must allocate the firm's limited resources between competing opportunities (projects).

Capital budgeting is also concerned with the setting of criteria about which projects should receive investment funding to increase the value of the firm, and whether to finance that investment with equity or debt capital.

Investments should be made on the basis of value-added to the future of the corporation. Projects that increase a firm's value may include a wide variety of different types of investments, including but not limited to, expansion policies, or mergers and acquisitions.

When no growth or expansion is possible by a corporation and excess cash surplus exists and is not needed, then management is expected to pay out some or all of those surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends or to repurchase the company's stock through a share buyback program.

Capital Structure:

Capitalization:

Main article: Capital structure

Further information: Security (finance)

Achieving the goals of corporate finance requires that any corporate investment be financed appropriately. The sources of financing are, generically, capital self-generated by the firm and capital from external funders, obtained by issuing new debt and equity (and hybrid- or convertible securities).

As above, since both hurdle rate and cash flows (and hence the riskiness of the firm) will be affected, the financing mix will impact the valuation of the firm. There are two interrelated considerations here:

- Management must identify the "optimal mix" of financing – the capital structure that results in maximum firm value, (See Balance sheet, WACC) but must also take other factors into account (see trade-off theory below). Financing a project through debt results in a liability or obligation that must be serviced, thus entailing cash flow implications independent of the project's degree of success. Equity financing is less risky with respect to cash flow commitments, but results in a dilution of share ownership, control and earnings. The cost of equity (see CAPM and APT) is also typically higher than the cost of debt - which is, additionally, a deductible expense – and so equity financing may result in an increased hurdle rate which may offset any reduction in cash flow risk.

- Management must attempt to match the long-term financing mix to the assets being financed as closely as possible, in terms of both timing and cash flows. Managing any potential asset liability mismatch or duration gap entails matching the assets and liabilities respectively according to maturity pattern ("Cashflow matching") or duration ("immunization"); managing this relationship in the short-term is a major function of working capital management, as discussed below. Other techniques, such as securitization, or hedging using interest rate- or credit derivatives, are also common. See Asset liability management; Treasury management; Credit risk; Interest rate risk.