Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

This Web Page

"Being Human"

covers how we,

both collectively and individually, have evolved/devolved to become today's human beings!

See also related web pages:

American Lifestyles

Modern Medicine

Civilization

Human Sexuality

Worst of Humanity

Human Beings, including a Timeline

YouTube Video: Evolution - from ape man to neanderthal - BBC science

Modern humans (Homo sapiens, primarily ssp. Homo sapiens sapiens) are the only extant members of the subtribe Hominina, a branch of the tribe Hominini belonging to the family of great apes.

Humans are characterized by erect posture and bipedal locomotion; high manual dexterity and heavy tool use compared to other animals; and a general trend toward larger, more complex brains and societies.

Early hominins—particularly the australopithecines, whose brains and anatomy are in many ways more similar to ancestral non-human apes—are less often referred to as "human" than hominins of the genus Homo. Several of these hominins used fire, occupied much of Eurasia, and gave rise to anatomically modern Homo sapiens in Africa about 200,000 years ago. They began to exhibit evidence of behavioral modernity around 50,000 years ago. In several waves of migration, anatomically modern humans ventured out of Africa and populated most of the world.

The spread of humans and their large and increasing population has had a profound impact on large areas of the environment and millions of native species worldwide.

Advantages that explain this evolutionary success include a relatively larger brain with a particularly well-developed neocortex, prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes, which enable high levels of abstract reasoning, language, problem solving, sociality, and culture through social learning.

Humans use tools to a much higher degree than any other animal, are the only extant species known to build fires and cook their food, and are the only extant species to clothe themselves and create and use numerous other technologies and arts.

Humans are uniquely adept at utilizing systems of symbolic communication (such as language and art) for self-expression and the exchange of ideas, and for organizing themselves into purposeful groups. Humans create complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families and kinship networks to political states.

Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety of values, social norms, and rituals, which together form the basis of human society. Curiosity and the human desire to understand and influence the environment and to explain and manipulate phenomena (or events) has provided the foundation for developing science, philosophy, mythology, religion, anthropology, and numerous other fields of knowledge.

Though most of human existence has been sustained by hunting and gathering in band societies, increasing numbers of human societies began to practice sedentary agriculture approximately some 10,000 years ago, domesticating plants and animals, thus allowing for the growth of civilization. These human societies subsequently expanded in size, establishing various forms of government, religion, and culture around the world, unifying people within regions to form states and empires.

The rapid advancement of scientific and medical understanding in the 19th and 20th centuries led to the development of fuel-driven technologies and increased lifespans, causing the human population to rise exponentially. Today the global human population is estimated by the United Nations to be near 7.5 billion.

In common usage, the word "human" generally refers to the only extant species of the genus Homo—anatomically and behaviorally modern Homo sapiens.

In scientific terms, the meanings of "hominid" and "hominin" have changed during the recent decades with advances in the discovery and study of the fossil ancestors of modern humans.

The previously clear boundary between humans and apes has blurred, resulting in now acknowledging the hominids as encompassing multiple species, and Homo and close relatives since the split from chimpanzees as the only hominins. There is also a distinction between anatomically modern humans and Archaic Homo sapiens, the earliest fossil members of the species.

The English adjective human is a Middle English term from Old French humain, ultimately from Latin hūmānus, the adjective form of homō "man." The word's use as a noun (with a plural: humans) dates to the 16th century. The native English term man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for humanity), and could formerly refer to specific individuals of either sex, though this latter use is now obsolete.

The species binomial Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th century work Systema Naturae. The generic name Homo is a learned 18th century derivation from Latin homō "man," ultimately "earthly being". The species-name sapiens means "wise" or "sapient." Note that the Latin word homo refers to humans of either gender, and that sapiens is the singular form (while there is no such word as sapien).

Evolution and range -- Main article: Human evolution

Further information: Anthropology, Homo (genus), and Timeline of human evolution.

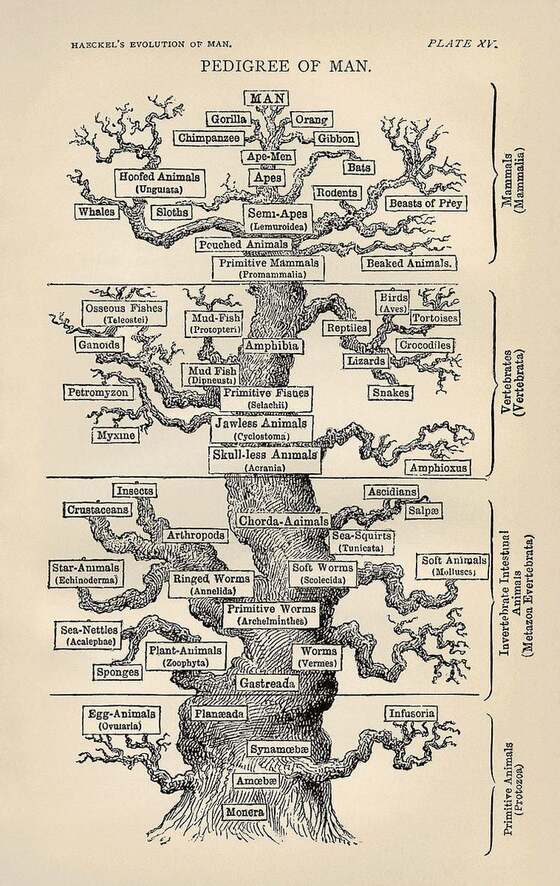

The genus Homo evolved and diverged from other hominins in Africa, after the human clade split from the chimpanzee lineage of the hominids (great apes) branch of the primates.

Modern humans, defined as the species Homo sapiens or specifically to the single extant subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Eurasia 125,000–60,000 years ago, Australia around 40,000 years ago, the Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand between the years 300 and 1280.

The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees (genus Pan) and gorillas (genus Gorilla). With the sequencing of both the human and chimpanzee genome, current estimates of similarity between human and chimpanzee DNA sequences range between 95% and 99%.

By using the technique called a molecular clock which estimates the time required for the number of divergent mutations to accumulate between two lineages, the approximate date for the split between lineages can be calculated. The gibbons (family Hylobatidae) and orangutans (genus Pongo) were the first groups to split from the line leading to the humans, then gorillas (genus Gorilla) followed by the chimpanzees (genus Pan).

The splitting date between human and chimpanzee lineages is placed around 4–8 million years ago during the late Miocene epoch. During this split, chromosome 2 was formed from two other chromosomes, leaving humans with only 23 pairs of chromosomes, compared to 24 for the other apes.

Evidence from the fossil record: There is little fossil evidence for the divergence of the gorilla, chimpanzee and hominin lineages. The earliest fossils that have been proposed as members of the hominin lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis dating from 7 million years ago, Orrorin tugenensis dating from 5.7 million years ago, and Ardipithecus kadabba dating to 5.6 million years ago.

Each of these species has been argued to be a bipedal ancestor of later hominins, but all such claims are contested. It is also possible that any one of the three is an ancestor of another branch of African apes, or is an ancestor shared between hominins and other African Hominoidea (apes).

The question of the relation between these early fossil species and the hominin lineage is still to be resolved. From these early species the australopithecines arose around 4 million years ago diverged into robust (also called Paranthropus) and gracile branches, possibly one of which (such as A. garhi, dating to 2.5 million years ago) is a direct ancestor of the genus Homo.

The earliest members of the genus Homo are Homo habilis which evolved around 2.8 million years ago. Homo habilis has been considered the first species for which there is clear evidence of the use of stone tools. More recently, however, in 2015, stone tools, perhaps predating Homo habilis, have been discovered in northwestern Kenya that have been dated to 3.3 million years old. Nonetheless, the brains of Homo habilis were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, and their main adaptation was bipedalism as an adaptation to terrestrial living.

During the next million years a process of encephalization began, and with the arrival of Homo erectus in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled. Homo erectus were the first of the hominina to leave Africa, and these species spread through Africa, Asia, and Europe between 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago.

One population of H. erectus, also sometimes classified as a separate species Homo ergaster, stayed in Africa and evolved into Homo sapiens. It is believed that these species were the first to use fire and complex tools.

The earliest transitional fossils between H. ergaster/erectus and archaic humans are from Africa such as Homo rhodesiensis, but seemingly transitional forms are also found at Dmanisi, Georgia. These descendants of African H. erectus spread through Eurasia from ca. 500,000 years ago evolving into H. antecessor, H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis.

The earliest fossils of anatomically modern humans are from the Middle Paleolithic, about 200,000 years ago such as the Omo remains of Ethiopia and the fossils of Herto sometimes classified as Homo sapiens idaltu. Later fossils of archaic Homo sapiens from Skhul in Israel and Southern Europe begin around 90,000 years ago.

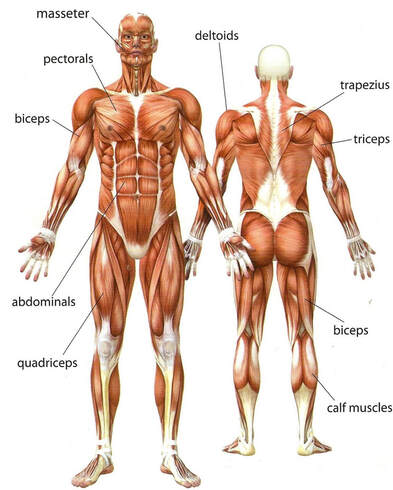

Anatomical adaptations:

Human evolution is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes that have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.

The most significant of these adaptations are 1. bipedalism, 2. increased brain size, 3. lengthened ontogeny (gestation and infancy), 4. decreased sexual dimorphism (neoteny). The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate. Other significant morphological changes included the evolution of a power and precision grip, a change first occurring in H. erectus.

Bipedalism is the basic adaption of the hominin line, and it is considered the main cause behind a suite of skeletal changes shared by all bipedal hominins. The earliest bipedal hominin is considered to be either Sahelanthropus or Orrorin, with Ardipithecus, a full bipedal, coming somewhat later.

The knuckle walkers, the gorilla and chimpanzee, diverged around the same time, and either Sahelanthropus or Orrorin may be humans' last shared ancestor with those animals. The early bipedals eventually evolved into the australopithecines and later the genus Homo.

There are several theories of the adaptational value of bipedalism. It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed up the hands for reaching and carrying food, because it saved energy during locomotion, because it enabled long distance running and hunting, or as a strategy for avoiding hyperthermia by reducing the surface exposed to direct sun.

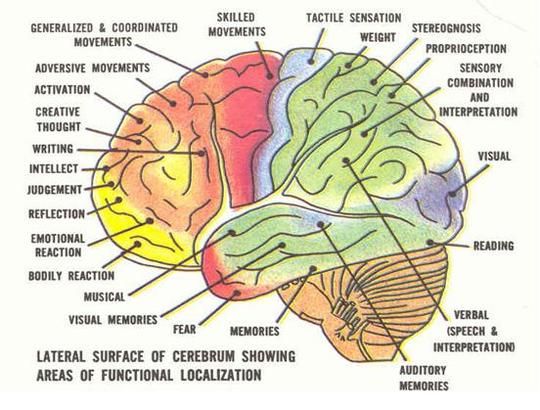

The human species developed a much larger brain than that of other primates—typically 1,330 cm3 (81 cu in) in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.

The pattern of encephalization started with Homo habilis which at approximately 600 cm3 (37 cu in) had a brain slightly larger than chimpanzees, and continued with Homo erectus (800–1,100 cm3 (49–67 cu in)), and reached a maximum in Neanderthals with an average size of 1,200–1,900 cm3 (73–116 cu in), larger even than Homo sapiens (but less encephalized).

The pattern of human postnatal brain growth differs from that of other apes (heterochrony), and allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans. However, the differences between the structure of human brains and those of other apes may be even more significant than differences in size.

The increase in volume over time has affected different areas within the brain unequally – the temporal lobes, which contain centers for language processing have increased disproportionately, as has the prefrontal cortex which has been related to complex decision making and moderating social behavior.

Encephalization has been tied to an increasing emphasis on meat in the diet, or with the development of cooking, and it has been proposed that intelligence increased as a response to an increased necessity for solving social problems as human society became more complex.

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is primarily visible in the reduction of the male canine tooth relative to other ape species (except gibbons). Another important physiological change related to sexuality in humans was the evolution of hidden estrus.

Humans are the only ape in which the female is fertile year round, and in which no special signals of fertility are produced by the body (such as genital swelling during estrus). Nonetheless humans retain a degree of sexual dimorphism in the distribution of body hair and subcutaneous fat, and in the overall size, males being around 25% larger than females.

These changes taken together have been interpreted as a result of an increased emphasis on pair bonding as a possible solution to the requirement for increased parental investment due to the prolonged infancy of offspring.

Rise of Homo sapiens:

Further information:

World map of early human migrations according to mitochondrial population genetics (numbers are millennia before present, the North Pole is at the center).

By the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 BP), full behavioral modernity, including language, music and other cultural universals had developed. As modern humans spread out from Africa they encountered other hominids such as Homo neanderthalensis and the so-called Denisovans.

The nature of interaction between early humans and these sister species has been a long-standing source of controversy, the question being whether humans replaced these earlier species or whether they were in fact similar enough to interbreed, in which case these earlier populations may have contributed genetic material to modern humans.

Recent studies of the human and Neanderthal genomes suggest gene flow between archaic Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and Denisovans. In March 2016, studies were published that suggest that modern humans bred with hominins, including Denisovans and Neanderthals, on multiple occasions.

This dispersal out of Africa is estimated to have begun about 70,000 years BP from Northeast Africa. Current evidence suggests that there was only one such dispersal and that it only involved a few hundred individuals. The vast majority of humans stayed in Africa and adapted to a diverse array of environments. Modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing earlier hominins (either through competition or hybridization). They inhabited Eurasia and Oceania by 40,000 years BP, and the Americas at least 14,500 years BP.

Transition to civilization:

Main articles: Neolithic Revolution and Cradle of civilization

Further information: History of the world

The rise of agriculture, and domestication of animals, led to stable human settlements. Until about 10,000 years ago, humans lived as hunter-gatherers. They gradually gained domination over much of the natural environment. They generally lived in small nomadic groups known as band societies, often in caves.

The advent of agriculture prompted the Neolithic Revolution, when access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals and the use of metal tools for the first time in history. Agriculture encouraged trade and cooperation, and led to complex society.

The early civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Maya, Greece and Rome were some of the cradles of civilization. The Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period saw the rise of revolutionary ideas and technologies.

Over the next 500 years, exploration and European colonialism brought great parts of the world under European control, leading to later struggles for independence. The concept of the modern world as distinct from an ancient world is based on a rapid change progress in a brief period of time in many areas.

Advances in all areas of human activity prompted new theories such as evolution and psychoanalysis, which changed humanity's views of itself.

The Scientific Revolution, Technological Revolution and the Industrial Revolution up until the 19th century resulted in independent discoveries such as imaging technology, major innovations in transport, such as the airplane and automobile; energy development, such as coal and electricity. This correlates with population growth (especially in America) and higher life expectancy, the World population rapidly increased numerous times in the 19th and 20th centuries as nearly 10% of the 100 billion people lived in the past century.

With the advent of the Information Age at the end of the 20th century, modern humans live in a world that has become increasingly globalized and interconnected. As of 2010, almost 2 billion humans are able to communicate with each other via the Internet, and 3.3 billion by mobile phone subscriptions.

Although interconnection between humans has encouraged the growth of science, art, discussion, and technology, it has also led to culture clashes and the development and use of weapons of mass destruction.

Human civilization has led to environmental destruction and pollution significantly contributing to the ongoing mass extinction of other forms of life called the Holocene extinction event, which may be further accelerated by global warming in the future.

Click on any of the following for more about Human Beings:

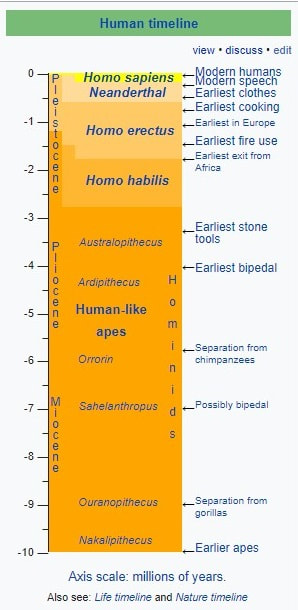

Timeline of human evolution

The timeline of human evolution outlines the major events in the development of the human species, Homo sapiens, and the evolution of our ancestors. It includes brief explanations of some of the species, genera, and the higher ranks of taxa that are seen today as possible ancestors of modern humans.

This timeline is based on studies from anthropology, paleontology, developmental biology, morphology, and from anatomical and genetic data. It does not address the origin of life, which discussion is provided by abiogenesis, but presents one possible line of evolutionary descent of species that eventually led to humans.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Timeline of Human Evolution:

Humans are characterized by erect posture and bipedal locomotion; high manual dexterity and heavy tool use compared to other animals; and a general trend toward larger, more complex brains and societies.

Early hominins—particularly the australopithecines, whose brains and anatomy are in many ways more similar to ancestral non-human apes—are less often referred to as "human" than hominins of the genus Homo. Several of these hominins used fire, occupied much of Eurasia, and gave rise to anatomically modern Homo sapiens in Africa about 200,000 years ago. They began to exhibit evidence of behavioral modernity around 50,000 years ago. In several waves of migration, anatomically modern humans ventured out of Africa and populated most of the world.

The spread of humans and their large and increasing population has had a profound impact on large areas of the environment and millions of native species worldwide.

Advantages that explain this evolutionary success include a relatively larger brain with a particularly well-developed neocortex, prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes, which enable high levels of abstract reasoning, language, problem solving, sociality, and culture through social learning.

Humans use tools to a much higher degree than any other animal, are the only extant species known to build fires and cook their food, and are the only extant species to clothe themselves and create and use numerous other technologies and arts.

Humans are uniquely adept at utilizing systems of symbolic communication (such as language and art) for self-expression and the exchange of ideas, and for organizing themselves into purposeful groups. Humans create complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families and kinship networks to political states.

Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety of values, social norms, and rituals, which together form the basis of human society. Curiosity and the human desire to understand and influence the environment and to explain and manipulate phenomena (or events) has provided the foundation for developing science, philosophy, mythology, religion, anthropology, and numerous other fields of knowledge.

Though most of human existence has been sustained by hunting and gathering in band societies, increasing numbers of human societies began to practice sedentary agriculture approximately some 10,000 years ago, domesticating plants and animals, thus allowing for the growth of civilization. These human societies subsequently expanded in size, establishing various forms of government, religion, and culture around the world, unifying people within regions to form states and empires.

The rapid advancement of scientific and medical understanding in the 19th and 20th centuries led to the development of fuel-driven technologies and increased lifespans, causing the human population to rise exponentially. Today the global human population is estimated by the United Nations to be near 7.5 billion.

In common usage, the word "human" generally refers to the only extant species of the genus Homo—anatomically and behaviorally modern Homo sapiens.

In scientific terms, the meanings of "hominid" and "hominin" have changed during the recent decades with advances in the discovery and study of the fossil ancestors of modern humans.

The previously clear boundary between humans and apes has blurred, resulting in now acknowledging the hominids as encompassing multiple species, and Homo and close relatives since the split from chimpanzees as the only hominins. There is also a distinction between anatomically modern humans and Archaic Homo sapiens, the earliest fossil members of the species.

The English adjective human is a Middle English term from Old French humain, ultimately from Latin hūmānus, the adjective form of homō "man." The word's use as a noun (with a plural: humans) dates to the 16th century. The native English term man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for humanity), and could formerly refer to specific individuals of either sex, though this latter use is now obsolete.

The species binomial Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th century work Systema Naturae. The generic name Homo is a learned 18th century derivation from Latin homō "man," ultimately "earthly being". The species-name sapiens means "wise" or "sapient." Note that the Latin word homo refers to humans of either gender, and that sapiens is the singular form (while there is no such word as sapien).

Evolution and range -- Main article: Human evolution

Further information: Anthropology, Homo (genus), and Timeline of human evolution.

The genus Homo evolved and diverged from other hominins in Africa, after the human clade split from the chimpanzee lineage of the hominids (great apes) branch of the primates.

Modern humans, defined as the species Homo sapiens or specifically to the single extant subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Eurasia 125,000–60,000 years ago, Australia around 40,000 years ago, the Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand between the years 300 and 1280.

The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees (genus Pan) and gorillas (genus Gorilla). With the sequencing of both the human and chimpanzee genome, current estimates of similarity between human and chimpanzee DNA sequences range between 95% and 99%.

By using the technique called a molecular clock which estimates the time required for the number of divergent mutations to accumulate between two lineages, the approximate date for the split between lineages can be calculated. The gibbons (family Hylobatidae) and orangutans (genus Pongo) were the first groups to split from the line leading to the humans, then gorillas (genus Gorilla) followed by the chimpanzees (genus Pan).

The splitting date between human and chimpanzee lineages is placed around 4–8 million years ago during the late Miocene epoch. During this split, chromosome 2 was formed from two other chromosomes, leaving humans with only 23 pairs of chromosomes, compared to 24 for the other apes.

Evidence from the fossil record: There is little fossil evidence for the divergence of the gorilla, chimpanzee and hominin lineages. The earliest fossils that have been proposed as members of the hominin lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis dating from 7 million years ago, Orrorin tugenensis dating from 5.7 million years ago, and Ardipithecus kadabba dating to 5.6 million years ago.

Each of these species has been argued to be a bipedal ancestor of later hominins, but all such claims are contested. It is also possible that any one of the three is an ancestor of another branch of African apes, or is an ancestor shared between hominins and other African Hominoidea (apes).

The question of the relation between these early fossil species and the hominin lineage is still to be resolved. From these early species the australopithecines arose around 4 million years ago diverged into robust (also called Paranthropus) and gracile branches, possibly one of which (such as A. garhi, dating to 2.5 million years ago) is a direct ancestor of the genus Homo.

The earliest members of the genus Homo are Homo habilis which evolved around 2.8 million years ago. Homo habilis has been considered the first species for which there is clear evidence of the use of stone tools. More recently, however, in 2015, stone tools, perhaps predating Homo habilis, have been discovered in northwestern Kenya that have been dated to 3.3 million years old. Nonetheless, the brains of Homo habilis were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, and their main adaptation was bipedalism as an adaptation to terrestrial living.

During the next million years a process of encephalization began, and with the arrival of Homo erectus in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled. Homo erectus were the first of the hominina to leave Africa, and these species spread through Africa, Asia, and Europe between 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago.

One population of H. erectus, also sometimes classified as a separate species Homo ergaster, stayed in Africa and evolved into Homo sapiens. It is believed that these species were the first to use fire and complex tools.

The earliest transitional fossils between H. ergaster/erectus and archaic humans are from Africa such as Homo rhodesiensis, but seemingly transitional forms are also found at Dmanisi, Georgia. These descendants of African H. erectus spread through Eurasia from ca. 500,000 years ago evolving into H. antecessor, H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis.

The earliest fossils of anatomically modern humans are from the Middle Paleolithic, about 200,000 years ago such as the Omo remains of Ethiopia and the fossils of Herto sometimes classified as Homo sapiens idaltu. Later fossils of archaic Homo sapiens from Skhul in Israel and Southern Europe begin around 90,000 years ago.

Anatomical adaptations:

Human evolution is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes that have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.

The most significant of these adaptations are 1. bipedalism, 2. increased brain size, 3. lengthened ontogeny (gestation and infancy), 4. decreased sexual dimorphism (neoteny). The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate. Other significant morphological changes included the evolution of a power and precision grip, a change first occurring in H. erectus.

Bipedalism is the basic adaption of the hominin line, and it is considered the main cause behind a suite of skeletal changes shared by all bipedal hominins. The earliest bipedal hominin is considered to be either Sahelanthropus or Orrorin, with Ardipithecus, a full bipedal, coming somewhat later.

The knuckle walkers, the gorilla and chimpanzee, diverged around the same time, and either Sahelanthropus or Orrorin may be humans' last shared ancestor with those animals. The early bipedals eventually evolved into the australopithecines and later the genus Homo.

There are several theories of the adaptational value of bipedalism. It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed up the hands for reaching and carrying food, because it saved energy during locomotion, because it enabled long distance running and hunting, or as a strategy for avoiding hyperthermia by reducing the surface exposed to direct sun.

The human species developed a much larger brain than that of other primates—typically 1,330 cm3 (81 cu in) in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.

The pattern of encephalization started with Homo habilis which at approximately 600 cm3 (37 cu in) had a brain slightly larger than chimpanzees, and continued with Homo erectus (800–1,100 cm3 (49–67 cu in)), and reached a maximum in Neanderthals with an average size of 1,200–1,900 cm3 (73–116 cu in), larger even than Homo sapiens (but less encephalized).

The pattern of human postnatal brain growth differs from that of other apes (heterochrony), and allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans. However, the differences between the structure of human brains and those of other apes may be even more significant than differences in size.

The increase in volume over time has affected different areas within the brain unequally – the temporal lobes, which contain centers for language processing have increased disproportionately, as has the prefrontal cortex which has been related to complex decision making and moderating social behavior.

Encephalization has been tied to an increasing emphasis on meat in the diet, or with the development of cooking, and it has been proposed that intelligence increased as a response to an increased necessity for solving social problems as human society became more complex.

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is primarily visible in the reduction of the male canine tooth relative to other ape species (except gibbons). Another important physiological change related to sexuality in humans was the evolution of hidden estrus.

Humans are the only ape in which the female is fertile year round, and in which no special signals of fertility are produced by the body (such as genital swelling during estrus). Nonetheless humans retain a degree of sexual dimorphism in the distribution of body hair and subcutaneous fat, and in the overall size, males being around 25% larger than females.

These changes taken together have been interpreted as a result of an increased emphasis on pair bonding as a possible solution to the requirement for increased parental investment due to the prolonged infancy of offspring.

Rise of Homo sapiens:

Further information:

- Recent African origin of modern humans,

- Multiregional origin of modern humans,

- Anatomically modern humans,

- Archaic human admixture with modern humans,

- and Early human migrations

World map of early human migrations according to mitochondrial population genetics (numbers are millennia before present, the North Pole is at the center).

By the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 BP), full behavioral modernity, including language, music and other cultural universals had developed. As modern humans spread out from Africa they encountered other hominids such as Homo neanderthalensis and the so-called Denisovans.

The nature of interaction between early humans and these sister species has been a long-standing source of controversy, the question being whether humans replaced these earlier species or whether they were in fact similar enough to interbreed, in which case these earlier populations may have contributed genetic material to modern humans.

Recent studies of the human and Neanderthal genomes suggest gene flow between archaic Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and Denisovans. In March 2016, studies were published that suggest that modern humans bred with hominins, including Denisovans and Neanderthals, on multiple occasions.

This dispersal out of Africa is estimated to have begun about 70,000 years BP from Northeast Africa. Current evidence suggests that there was only one such dispersal and that it only involved a few hundred individuals. The vast majority of humans stayed in Africa and adapted to a diverse array of environments. Modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing earlier hominins (either through competition or hybridization). They inhabited Eurasia and Oceania by 40,000 years BP, and the Americas at least 14,500 years BP.

Transition to civilization:

Main articles: Neolithic Revolution and Cradle of civilization

Further information: History of the world

The rise of agriculture, and domestication of animals, led to stable human settlements. Until about 10,000 years ago, humans lived as hunter-gatherers. They gradually gained domination over much of the natural environment. They generally lived in small nomadic groups known as band societies, often in caves.

The advent of agriculture prompted the Neolithic Revolution, when access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals and the use of metal tools for the first time in history. Agriculture encouraged trade and cooperation, and led to complex society.

The early civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Maya, Greece and Rome were some of the cradles of civilization. The Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period saw the rise of revolutionary ideas and technologies.

Over the next 500 years, exploration and European colonialism brought great parts of the world under European control, leading to later struggles for independence. The concept of the modern world as distinct from an ancient world is based on a rapid change progress in a brief period of time in many areas.

Advances in all areas of human activity prompted new theories such as evolution and psychoanalysis, which changed humanity's views of itself.

The Scientific Revolution, Technological Revolution and the Industrial Revolution up until the 19th century resulted in independent discoveries such as imaging technology, major innovations in transport, such as the airplane and automobile; energy development, such as coal and electricity. This correlates with population growth (especially in America) and higher life expectancy, the World population rapidly increased numerous times in the 19th and 20th centuries as nearly 10% of the 100 billion people lived in the past century.

With the advent of the Information Age at the end of the 20th century, modern humans live in a world that has become increasingly globalized and interconnected. As of 2010, almost 2 billion humans are able to communicate with each other via the Internet, and 3.3 billion by mobile phone subscriptions.

Although interconnection between humans has encouraged the growth of science, art, discussion, and technology, it has also led to culture clashes and the development and use of weapons of mass destruction.

Human civilization has led to environmental destruction and pollution significantly contributing to the ongoing mass extinction of other forms of life called the Holocene extinction event, which may be further accelerated by global warming in the future.

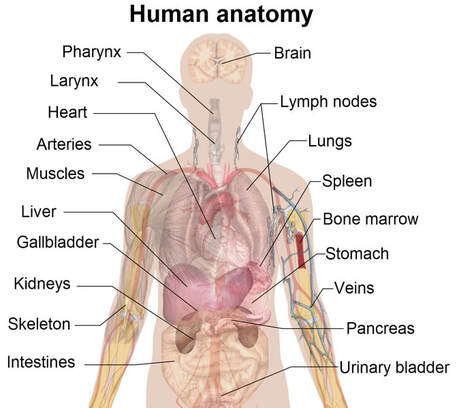

Click on any of the following for more about Human Beings:

- Habitat and population

- Biology

- Psychology

- Behavior

- See also:

- Holocene calendar

- Human impact on the environment

- Dawn of Humanity – a 2015 PBS film

- Human timeline

- Life timeline

- List of human evolution fossils

- Nature timeline

- Archaeology Info

- Homo sapiens – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 at the Encyclopedia of Life

- View the human genome on Ensembl

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Timeline of human evolution

The timeline of human evolution outlines the major events in the development of the human species, Homo sapiens, and the evolution of our ancestors. It includes brief explanations of some of the species, genera, and the higher ranks of taxa that are seen today as possible ancestors of modern humans.

This timeline is based on studies from anthropology, paleontology, developmental biology, morphology, and from anatomical and genetic data. It does not address the origin of life, which discussion is provided by abiogenesis, but presents one possible line of evolutionary descent of species that eventually led to humans.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Timeline of Human Evolution:

- Taxonomy of Homo sapiens

- Timeline

- See also:

- Chimpanzee-human last common ancestor

- Dawn of Humanity (film)

- Homininae

- Human evolution

- Human taxonomy

- Human timeline

- Homo

- Life timeline

- Most recent common ancestor

- List of human evolution fossils

- March of Progress – famous illustration of 25 million years of human evolution

- Nature timeline

- Prehistoric amphibian

- Prehistoric Autopsy

- Prehistoric fish

- Prehistoric reptile

- The Ancestor's Tale by Richard Dawkins – timeline comprising 40 rendezvous points

- Timeline of evolution – explains the evolution of animals living today

- Timeline of prehistory

- Y-DNA haplogroups by ethnic groups

- General:

- Palaeos

- Berkeley Evolution

- History of Animal Evolution

- Tree of Life Web Project – explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Evolution including Today's Homo SapiensPictured: The seven stages of the evolution of Mankind

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations.

Evolutionary processes give rise to biodiversity at every level of biological organization, including the levels of species, individual organisms, and molecules.

Repeated formation of new species (speciation), change within species (anagenesis), and loss of species (extinction) throughout the evolutionary history of life on Earth are demonstrated by shared sets of morphological and biochemical traits, including shared DNA sequences.

These shared traits are more similar among species that share a more recent common ancestor, and can be used to reconstruct a biological "tree of life" based on evolutionary relationships (phylogenetics), using both existing species and fossils. The fossil record includes a progression from early biogenic graphite, to microbial mat fossils, to fossilized multicellular organisms. Existing patterns of biodiversity have been shaped both by speciation and by extinction.

In the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin formulated the scientific theory of evolution by natural selection, published in his book On the Origin of Species (1859). Evolution by natural selection is a process demonstrated by the observation that more offspring are produced than can possibly survive, along with three facts about populations:

This teleonomy is the quality whereby the process of natural selection creates and preserves traits that are seemingly fitted for the functional roles they perform. The processes by which the changes occur, from one generation to another, are called evolutionary processes or mechanisms.

The four most widely recognized evolutionary processes are: natural selection (including sexual selection), genetic drift, mutation and gene migration due to genetic admixture. Natural selection and genetic drift sort variation; mutation and gene migration create variation.

Consequences of selection can include meiotic drive (unequal transmission of certain alleles), nonrandom mating and genetic hitchhiking.

In the early 20th century the modern evolutionary synthesis integrated classical genetics with Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection through the discipline of population genetics.

The importance of natural selection as a cause of evolution was accepted into other branches of biology. Moreover, previously held notions about evolution, such as orthogenesis, evolutionism, and other beliefs about innate "progress" within the largest-scale trends in evolution, became obsolete.

Scientists continue to study various aspects of evolutionary biology by forming and testing hypotheses, constructing mathematical models of theoretical biology and biological theories, using observational data, and performing experiments in both the field and the laboratory.

All life on Earth shares a common ancestor known as the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), which lived approximately 3.5–3.8 billion years ago. This should not be assumed to be the first living organism on Earth; a study in 2015 found "remains of biotic life" from 4.1 billion years ago in ancient rocks in Western Australia.

In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the LUCA of all organisms living on Earth. More than 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.

Estimates of Earth's current species range from 10 to 14 million, of which about 1.9 million are estimated to have been named and 1.6 million documented in a central database to date.

More recently, in May 2016, scientists reported that 1 trillion species are estimated to be on Earth currently with only one-thousandth of one percent described.

In terms of practical application, an understanding of evolution has been instrumental to developments in numerous scientific and industrial fields, including agriculture, human and veterinary medicine, and the life sciences in general.

Discoveries in evolutionary biology have made a significant impact not just in the traditional branches of biology but also in other academic disciplines, including biological anthropology, and evolutionary psychology. Evolutionary computation, a sub-field of artificial intelligence, involves the application of Darwinian principles to problems in computer science.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Evolution:

Today's Homo Sapiens:

Homo sapiens is the only extant human species. The name is Latin for "wise man" and was introduced in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus (who is himself the lectotype for the species).

Extinct species of the genus Homo include Homo erectus, extant during roughly 1.9 to 0.4 million years ago, and a number of other species (by some authors considered subspecies of either H. sapiens or H. erectus).

The age of speciation of H. sapiens out of ancestral H. erectus (or an intermediate species such as Homo antecessor) is estimated to have been roughly 350,000 years ago. Sustained archaic admixture is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the recent Out-Of-Africa expansion) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 and 30,000 years ago.

The term anatomically modern humans (AMH) is used to distinguish H. sapiens having an anatomy consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from varieties of extinct archaic humans. This is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe.

By the early 2000s, it had become common to use H. s. sapiens for the ancestral population of all contemporary humans, and as such it is equivalent to the binomial H. sapiens in the more restrictive sense (considering H. neanderthalensis a separate species).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Homo Sapiens:

Evolutionary processes give rise to biodiversity at every level of biological organization, including the levels of species, individual organisms, and molecules.

Repeated formation of new species (speciation), change within species (anagenesis), and loss of species (extinction) throughout the evolutionary history of life on Earth are demonstrated by shared sets of morphological and biochemical traits, including shared DNA sequences.

These shared traits are more similar among species that share a more recent common ancestor, and can be used to reconstruct a biological "tree of life" based on evolutionary relationships (phylogenetics), using both existing species and fossils. The fossil record includes a progression from early biogenic graphite, to microbial mat fossils, to fossilized multicellular organisms. Existing patterns of biodiversity have been shaped both by speciation and by extinction.

In the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin formulated the scientific theory of evolution by natural selection, published in his book On the Origin of Species (1859). Evolution by natural selection is a process demonstrated by the observation that more offspring are produced than can possibly survive, along with three facts about populations:

- traits vary among individuals with respect to morphology, physiology, and behavior (phenotypic variation),

- different traits confer different rates of survival and reproduction (differential fitness),

- traits can be passed from generation to generation (heritability of fitness). Thus, in successive generations members of a population are replaced by progeny of parents better adapted to survive and reproduce in the biophysical environment in which natural selection takes place.

This teleonomy is the quality whereby the process of natural selection creates and preserves traits that are seemingly fitted for the functional roles they perform. The processes by which the changes occur, from one generation to another, are called evolutionary processes or mechanisms.

The four most widely recognized evolutionary processes are: natural selection (including sexual selection), genetic drift, mutation and gene migration due to genetic admixture. Natural selection and genetic drift sort variation; mutation and gene migration create variation.

Consequences of selection can include meiotic drive (unequal transmission of certain alleles), nonrandom mating and genetic hitchhiking.

In the early 20th century the modern evolutionary synthesis integrated classical genetics with Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection through the discipline of population genetics.

The importance of natural selection as a cause of evolution was accepted into other branches of biology. Moreover, previously held notions about evolution, such as orthogenesis, evolutionism, and other beliefs about innate "progress" within the largest-scale trends in evolution, became obsolete.

Scientists continue to study various aspects of evolutionary biology by forming and testing hypotheses, constructing mathematical models of theoretical biology and biological theories, using observational data, and performing experiments in both the field and the laboratory.

All life on Earth shares a common ancestor known as the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), which lived approximately 3.5–3.8 billion years ago. This should not be assumed to be the first living organism on Earth; a study in 2015 found "remains of biotic life" from 4.1 billion years ago in ancient rocks in Western Australia.

In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the LUCA of all organisms living on Earth. More than 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.

Estimates of Earth's current species range from 10 to 14 million, of which about 1.9 million are estimated to have been named and 1.6 million documented in a central database to date.

More recently, in May 2016, scientists reported that 1 trillion species are estimated to be on Earth currently with only one-thousandth of one percent described.

In terms of practical application, an understanding of evolution has been instrumental to developments in numerous scientific and industrial fields, including agriculture, human and veterinary medicine, and the life sciences in general.

Discoveries in evolutionary biology have made a significant impact not just in the traditional branches of biology but also in other academic disciplines, including biological anthropology, and evolutionary psychology. Evolutionary computation, a sub-field of artificial intelligence, involves the application of Darwinian principles to problems in computer science.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Evolution:

- History of evolutionary thought

- Heredity

- Variation

- Means:

- Outcomes

- Evolutionary history of life

- Applications

- Social and cultural responses

- See also:

- Argument from poor design

- Biocultural evolution

- Biological classification

- Evidence of common descent

- Evolutionary anthropology

- Evolutionary ecology

- Evolutionary epistemology

- Evolutionary neuroscience

- Evolution of biological complexity

- Evolution of plants

- Timeline of the evolutionary history of life

- Unintelligent design

- Universal Darwinism

- General information:

- Evolution on In Our Time at the BBC.

- "Evolution". New Scientist. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Evolution Resources from the National Academies". Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Understanding Evolution: your one-stop resource for information on evolution". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Evolution of Evolution – 150 Years of Darwin's 'On the Origin of Species'". Arlington County, VA: National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- Experiments concerning the process of biological evolution

- Lenski, Richard E. "Experimental Evolution". Michigan State University. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- Chastain, Erick; Livnat, Adi; Papadimitriou, Christos; Vazirani, Umesh (July 22, 2014). "Algorithms, games, and evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 111 (29): 10620–10623. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110620C. ISSN 0027-8424. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406556111. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- Online lectures

- Stearns, Stephen C. "Principles of Evolution, Ecology and Behavior". Retrieved 2011-08-30

Today's Homo Sapiens:

Homo sapiens is the only extant human species. The name is Latin for "wise man" and was introduced in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus (who is himself the lectotype for the species).

Extinct species of the genus Homo include Homo erectus, extant during roughly 1.9 to 0.4 million years ago, and a number of other species (by some authors considered subspecies of either H. sapiens or H. erectus).

The age of speciation of H. sapiens out of ancestral H. erectus (or an intermediate species such as Homo antecessor) is estimated to have been roughly 350,000 years ago. Sustained archaic admixture is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the recent Out-Of-Africa expansion) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 and 30,000 years ago.

The term anatomically modern humans (AMH) is used to distinguish H. sapiens having an anatomy consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from varieties of extinct archaic humans. This is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe.

By the early 2000s, it had become common to use H. s. sapiens for the ancestral population of all contemporary humans, and as such it is equivalent to the binomial H. sapiens in the more restrictive sense (considering H. neanderthalensis a separate species).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Homo Sapiens:

- Name and taxonomy

- Age and speciation process

- Dispersal and archaic admixture

- Anatomy

- Recent evolution

- Behavioral modernity

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Adult Development

YouTube Video About Adult Development

YouTube Video: 7 Adulthood Myths You (Probably) Believe!

Adult development encompasses the changes that occur in biological and psychological domains of human life from the end of adolescence until the end of one's life. These changes may be gradual or rapid, and can reflect positive, negative, or no change from previous levels of functioning.

Changes occur at the cellular level and are partially explained by biological theories of adult development and aging.[1] Biological changes influence psychological and interpersonal/social developmental changes, which are often described by stage theories of human development. Stage theories typically focus on “age-appropriate” developmental tasks to be achieved at each stage.

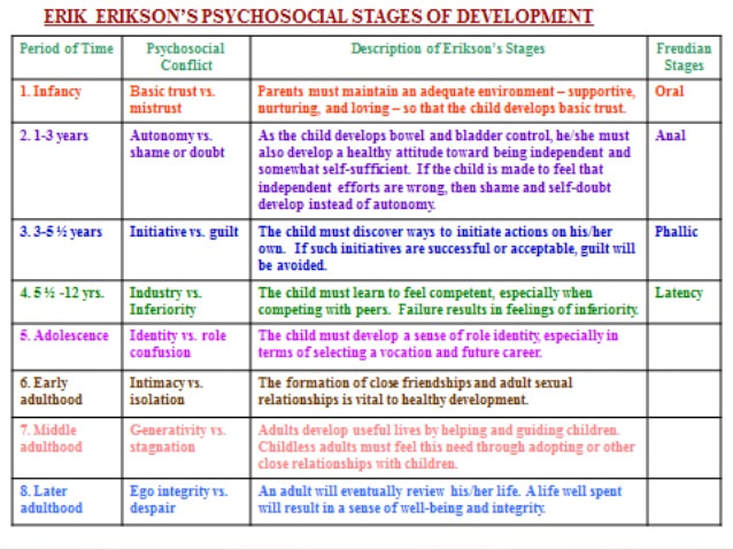

Erik Erikson and Carl Jung proposed stage theories of human development that encompass the entire life span, and emphasized the potential for positive change very late in life.

The concept of adulthood has legal and socio-cultural definitions. The legal definition of an adult is a person who has reached the age at which they are considered responsible for their own actions, and therefore legally accountable for them. This is referred to as the age of majority, which is age 18 in most cultures, although there is variation from 16 to 21.

The socio-cultural definition of being an adult is based on what a culture normally views as being the required criteria for adulthood, which in turn influences the life of individuals within that culture. This may or may not coincide with the legal definition. Current views on adult development in late life focus on the concept of successful aging, defined as “...low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life.”

Biomedical theories hold that one can age successfully by caring for physical health and minimizing loss in function, whereas psychosocial theories posit that capitalizing upon social and cognitive resources, such as a positive attitude or social support from neighbors and friends, is key to aging successfully.

Jeanne Louise Calment exemplifies successful aging as the longest living person, dying at the age of 122 years. Her long life can be attributed to her genetics (both parents lived into their 80s) and her active lifestyle and optimistic attitude. She enjoyed many hobbies and physical activities and believed that laughter contributed to her longevity. She poured olive oil on all of her food and skin, which she believed also contributed to her long life and youthful appearance.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Adult Development:

Changes occur at the cellular level and are partially explained by biological theories of adult development and aging.[1] Biological changes influence psychological and interpersonal/social developmental changes, which are often described by stage theories of human development. Stage theories typically focus on “age-appropriate” developmental tasks to be achieved at each stage.

Erik Erikson and Carl Jung proposed stage theories of human development that encompass the entire life span, and emphasized the potential for positive change very late in life.

The concept of adulthood has legal and socio-cultural definitions. The legal definition of an adult is a person who has reached the age at which they are considered responsible for their own actions, and therefore legally accountable for them. This is referred to as the age of majority, which is age 18 in most cultures, although there is variation from 16 to 21.

The socio-cultural definition of being an adult is based on what a culture normally views as being the required criteria for adulthood, which in turn influences the life of individuals within that culture. This may or may not coincide with the legal definition. Current views on adult development in late life focus on the concept of successful aging, defined as “...low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life.”

Biomedical theories hold that one can age successfully by caring for physical health and minimizing loss in function, whereas psychosocial theories posit that capitalizing upon social and cognitive resources, such as a positive attitude or social support from neighbors and friends, is key to aging successfully.

Jeanne Louise Calment exemplifies successful aging as the longest living person, dying at the age of 122 years. Her long life can be attributed to her genetics (both parents lived into their 80s) and her active lifestyle and optimistic attitude. She enjoyed many hobbies and physical activities and believed that laughter contributed to her longevity. She poured olive oil on all of her food and skin, which she believed also contributed to her long life and youthful appearance.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Adult Development:

- Contemporary and classic theories

- Non-normative cognitive changes in adulthood

- Mental health in adulthood and old age

- Optimizing health and mental well-being in adulthood

- Personality in adulthood

- Intelligence in adulthood

- Relationships

- Retirement

- Long term care

Childhood

YouTube Video About Childhood Development Stages

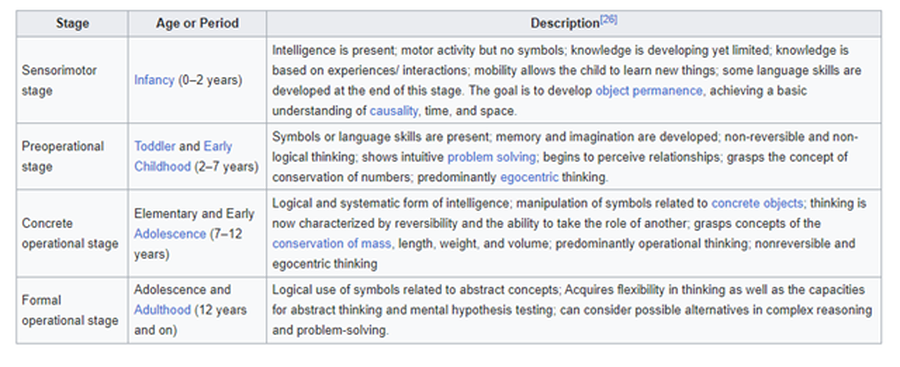

Childhood is the age span ranging from birth to adolescence. According to Piaget's theory of cognitive development, childhood consists of two stages: preoperational stage and concrete operational stage.

In developmental psychology, childhood is divided up into the developmental stages of:

Various childhood factors could affect a person's attitude formation. The concept of childhood emerged during the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly through the educational theories of the philosopher John Locke and the growth of books for and about children. Previous to this point, children were often seen as incomplete versions of adults.

Time span, age ranges:

The term childhood is non-specific in its time span and can imply a varying range of years in human development. Developmentally and biologically, it refers to the period between infancy and adulthood.

In common terms, childhood is considered to start from birth, and as a concept of play and innocence, which ends at adolescence.

In the legal systems of many countries, there is an age of majority when childhood legally ends and a person legally becomes an adult, which ranges anywhere from 15 to 21, with 18 being the most common.

A global consensus on the terms of childhood is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Childhood expectancy indicates the time span, which a child has to experience childhood.

Eight life events ending childhood have been described as death, extreme malnourishment, extreme violence, conflict forcing displacement, children being out of school, child labor, children having children and child marriage.

Developmental stages of childhood:

Early Childhood:

Early childhood follows the infancy stage and begins with toddlerhood when the child begins speaking or taking steps independently.

While toddlerhood ends around age three when the child becomes less dependent on parental assistance for basic needs, early childhood continues approximately through age nine.

According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children, early childhood spans the human life from birth to age eight. At this stage children are learning through observing, experimenting and communicating with others. Adults supervise and support the development process of the child, which then will lead to the child's autonomy. Also during this stage, a strong emotional bond is created between the child and the care providers. The children also start to begin kindergarten at this age to start their social lives.

Middle Childhood:

Middle childhood begins at around age ten approximating primary school age. It ends around puberty, which typically marks the beginning of adolescence. In this period, children are attending school, thus developing socially and mentally. They are at a stage where they make new friends and gain new skills, which will enable them to become more independent and enhance their individuality.

Adolescence:

Adolescence is usually determined by the onset of puberty, usually 12 for girls and 13 for boys. However, puberty may also begin in preadolescence. Adolescence is biological distinct from childhood, but it is accepted by some cultures as a part of social childhood, because most of them are minors.

The onset of adolescence brings about various physical, psychological and behavioral changes. The end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood varies by country and by function, and even within a single nation-state or culture there may be different ages at which an individual is considered to be mature enough to be entrusted by society with certain tasks.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Childhood:

In developmental psychology, childhood is divided up into the developmental stages of:

- infancy and toddlerhood (learning to walk and talk, ages birth to 4),

- early childhood (play age covering the kindergarten and early grade school years up to grade 4 (5-10 years old)),

- preadolescence, around 11 and 12 (where puberty could possibly begin in early developers but could equally be in early childhood if the child has not reached puberty),

- and adolescence (puberty (early adolescence, 13-15) through post-puberty (late adolescence, 16-19) ).

Various childhood factors could affect a person's attitude formation. The concept of childhood emerged during the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly through the educational theories of the philosopher John Locke and the growth of books for and about children. Previous to this point, children were often seen as incomplete versions of adults.

Time span, age ranges:

The term childhood is non-specific in its time span and can imply a varying range of years in human development. Developmentally and biologically, it refers to the period between infancy and adulthood.

In common terms, childhood is considered to start from birth, and as a concept of play and innocence, which ends at adolescence.

In the legal systems of many countries, there is an age of majority when childhood legally ends and a person legally becomes an adult, which ranges anywhere from 15 to 21, with 18 being the most common.

A global consensus on the terms of childhood is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Childhood expectancy indicates the time span, which a child has to experience childhood.

Eight life events ending childhood have been described as death, extreme malnourishment, extreme violence, conflict forcing displacement, children being out of school, child labor, children having children and child marriage.

Developmental stages of childhood:

Early Childhood:

Early childhood follows the infancy stage and begins with toddlerhood when the child begins speaking or taking steps independently.

While toddlerhood ends around age three when the child becomes less dependent on parental assistance for basic needs, early childhood continues approximately through age nine.

According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children, early childhood spans the human life from birth to age eight. At this stage children are learning through observing, experimenting and communicating with others. Adults supervise and support the development process of the child, which then will lead to the child's autonomy. Also during this stage, a strong emotional bond is created between the child and the care providers. The children also start to begin kindergarten at this age to start their social lives.

Middle Childhood:

Middle childhood begins at around age ten approximating primary school age. It ends around puberty, which typically marks the beginning of adolescence. In this period, children are attending school, thus developing socially and mentally. They are at a stage where they make new friends and gain new skills, which will enable them to become more independent and enhance their individuality.

Adolescence:

Adolescence is usually determined by the onset of puberty, usually 12 for girls and 13 for boys. However, puberty may also begin in preadolescence. Adolescence is biological distinct from childhood, but it is accepted by some cultures as a part of social childhood, because most of them are minors.

The onset of adolescence brings about various physical, psychological and behavioral changes. The end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood varies by country and by function, and even within a single nation-state or culture there may be different ages at which an individual is considered to be mature enough to be entrusted by society with certain tasks.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Childhood:

- History

- Modern concepts of childhood

- Geographies of childhood

- Nature deficit disorder

- Healthy childhoods

- Children's rights

- Research in social sciences

- See also:

- Birthday party

- Child

- Childhood and migration

- Childhood in Medieval England

- Children's party games

- Coming of age

- Developmental biology

- List of child related articles

- List of traditional children's games

- Rite of passage

- Sociology of childhood

- Street children

- Childhood on In Our Time at the BBC.

- World Childhood Foundation

- Meeting Early Childhood Needs

Demographics of the World

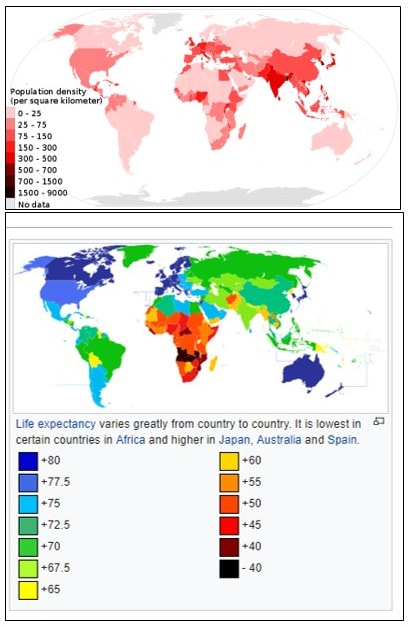

TOP Illustration: Population density (people per km2) by country, 2015 (Courtesy of Ms Sarah Welch - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

BOTTOM Illustration: Life expectancy varies greatly from country to country. It is lowest in certain countries in Africa and higher in Japan, Australia and Spain. (Courtesy of Fobos92 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0)

- YouTube Video: World population expected to increase by two billion in 30 yrs - Press Conference (17 June 2019)

- YouTube Video: Empty Planet: Preparing for the Global Population Decline

- YouTube Video: Human Population Through Time

TOP Illustration: Population density (people per km2) by country, 2015 (Courtesy of Ms Sarah Welch - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

BOTTOM Illustration: Life expectancy varies greatly from country to country. It is lowest in certain countries in Africa and higher in Japan, Australia and Spain. (Courtesy of Fobos92 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Demographics of the world include the following:

The overall total population of the world is approximately 7.45 billion, as of July 2016.

Its overall population density is 50 people per km² (129.28 per sq. mile), excluding Antarctica.

Nearly two-thirds of the population lives in Asia and is predominantly urban and suburban, with more than 2.5 billion in the countries of China and India combined. The World's fairly low literacy rate (83.7%) is attributable to impoverished regions. Extremely low literacy rates are concentrated in three regions, the Arab states, South and West Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The world's largest ethnic group is Han Chinese with Mandarin being the world's most spoken language in terms of native speakers.

Human migration has been shifting toward cities and urban centers, with the urban population jumping from 29% in 1950, to 50.5% in 2005. Working backwards from the United Nations prediction that the world will be 51.3 percent urban by 2010, Dr. Ron Wimberley, Dr. Libby Morris and Dr. Gregory Fulkerson estimated May 23, 2007 to be the first time the urban population outnumbered the rural population in history.

China and India are the most populous countries, as the birth rate has consistently dropped in developed countries and until recently remained high in developing countries. Tokyo is the largest urban conglomeration in the world.

The total fertility rate of the World is estimated as 2.52 children per woman, which is above the replacement fertility rate of approximately 2.1. However, world population growth is unevenly distributed, going from .91 in Macau, to 7.68 in Niger. The United Nations estimated an annual population increase of 1.14% for the year of 2000.

There are approximately 3.38 billion females in the World. The number of males is about 3.41 billion.

People under 14 years of age made up over a quarter of the world population (26.3%), and people age 65 and over made up less than one-tenth (7.9%) in 2011.

The world population growth is approximately 1.09%

The world population more than tripled during the 20th century from about 1.65 billion in 1900 to 5.97 billion in 1999. It reached the 2 billion mark in 1927, the 3 billion mark in 1960, 4 billion in 1974, and 5 billion in 1987. Currently, population growth is fastest among low wealth, Third World countries.

The UN projects a world population of 9.15 billion in 2050, which is a 32.69% increase from 2010 (6.89 billion).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Demographics of the World:

- population density,

- ethnicity,

- education level,

- health measures,

- economic status,

- religious affiliations

- and other aspects of the population.

The overall total population of the world is approximately 7.45 billion, as of July 2016.

Its overall population density is 50 people per km² (129.28 per sq. mile), excluding Antarctica.

Nearly two-thirds of the population lives in Asia and is predominantly urban and suburban, with more than 2.5 billion in the countries of China and India combined. The World's fairly low literacy rate (83.7%) is attributable to impoverished regions. Extremely low literacy rates are concentrated in three regions, the Arab states, South and West Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The world's largest ethnic group is Han Chinese with Mandarin being the world's most spoken language in terms of native speakers.

Human migration has been shifting toward cities and urban centers, with the urban population jumping from 29% in 1950, to 50.5% in 2005. Working backwards from the United Nations prediction that the world will be 51.3 percent urban by 2010, Dr. Ron Wimberley, Dr. Libby Morris and Dr. Gregory Fulkerson estimated May 23, 2007 to be the first time the urban population outnumbered the rural population in history.

China and India are the most populous countries, as the birth rate has consistently dropped in developed countries and until recently remained high in developing countries. Tokyo is the largest urban conglomeration in the world.

The total fertility rate of the World is estimated as 2.52 children per woman, which is above the replacement fertility rate of approximately 2.1. However, world population growth is unevenly distributed, going from .91 in Macau, to 7.68 in Niger. The United Nations estimated an annual population increase of 1.14% for the year of 2000.

There are approximately 3.38 billion females in the World. The number of males is about 3.41 billion.

People under 14 years of age made up over a quarter of the world population (26.3%), and people age 65 and over made up less than one-tenth (7.9%) in 2011.

The world population growth is approximately 1.09%

The world population more than tripled during the 20th century from about 1.65 billion in 1900 to 5.97 billion in 1999. It reached the 2 billion mark in 1927, the 3 billion mark in 1960, 4 billion in 1974, and 5 billion in 1987. Currently, population growth is fastest among low wealth, Third World countries.

The UN projects a world population of 9.15 billion in 2050, which is a 32.69% increase from 2010 (6.89 billion).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Demographics of the World:

- History

- Cities

- Population density

- Population distribution

- Ethnicity

- Religion

- Marriage

- Health

- Demographic statistics

- Languages

- Education

- See also:

Middle Age

YouTube Video: 35 min. LOW IMPACT AEROBIC WORKOUT - Fun and easy to follow for beginners and seniors!

Middle age is the period of age beyond young adulthood but before the onset of old age.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary middle age is between 45 and 65: "The period between early adulthood and old age, usually considered as the years from about 45 to 65."

The US Census lists the category middle age from 45 to 65. Merriam-Webster list middle age from 45 to 64, while prominent psychologist Erik Erikson saw it starting a little earlier and defines middle adulthood as between 40 and 65.

The Collins English Dictionary, list it between the ages of 40 and 60. and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - the standard diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association - used to define middle age as 40 to 60, but as of DSM-IV (1994) revised the definition upwards to 45 to 65.

Young Adulthood:

Further information: Young adult (psychology)

This time in the lifespan is considered to be the developmental stage of those who are between 20 years old and 40 years old. Recent developmental theories have recognized that development occurs across the entire life of a person as they experience changes cognitively, physically, socially, and in personality.

Middle Adulthood:

This time period in the life of a person can be referred to as middle age. This time span has been defined as the time between ages 45 to 65 years old.

Many changes may occur between young adulthood and this stage. The body may slow down and the middle aged might become more sensitive to diet, substance abuse, stress, and rest.

Chronic health problems can become an issue along with disability or disease.

Approximately one centimeter of height may be lost per decade. Emotional responses and retrospection vary from person to person. Experiencing a sense of mortality, sadness, or loss is common at this age.

Those in middle adulthood or middle age continue to develop relationships and adapt to the changes in relationships. Changes can be the interacting with growing and grown children and aging parents. Community involvement is fairly typical of this stage of adulthood,[8]as well as continued career development.

Physical Characteristics:

Middle-aged adults may begin to show visible signs of aging. This process can be more rapid in women who have osteoporosis. Changes might occur in the nervous system. The ability to perform complex tasks remains intact.

Women between 48 and 55 experience menopause, which ends natural fertility.

Menopause can have many side effects, some welcome and some not so welcome. Men may also experience physical changes. Changes can occur to skin and other changes may include decline in physical fitness including a reduction in aerobic performance and a decrease in maximal heart rate. These measurements are generalities and people may exhibit these changes at different rates and times.

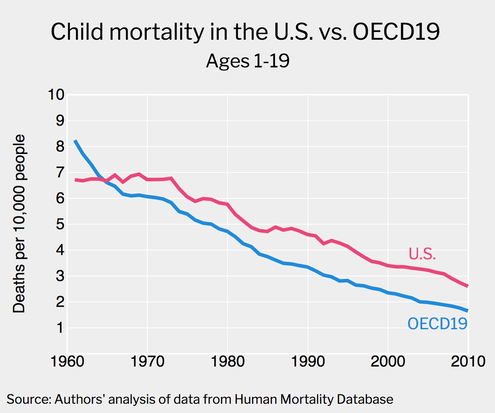

The mortality rate can begin to increase from 45 and onwards, mainly due to health problems like heart problems, cancer, hypertension, and diabetes.

Still, the majority of middle-aged people in industrialized nations can expect to live into old age.

Cognitive characteristics

Erik Erikson refers to this period of adulthood as the generavative-versus-stagnation stage. Persons in middle adulthood or middle age may have some cognitive loss. This loss usually remains unnoticeable because life experiences and strategies are developed to compensate for any decrease in mental abilities.

Social and personality characteristics

Marital satisfaction remains but other family relationships can be more difficult. Career satisfaction focuses more on inner satisfaction and contentedness and less on ambition and the desire to 'advance'.

Even so, career changes often can occur. Middle adulthood or middle age can be a time when a person re-examines their life by taking stock, and evaluating their accomplishments.

Morality may change and become more conscious. The perception that those in this stage of development or life undergo a 'mid-life' crisis is largely false. This period in life is usually satisfying, tranquil.

Personality characteristics remain stable throughout this period. This may make the issue of mortality irrefutable. The relationships in middle adulthood may continue to evolve into connections that are stable.

See also:

According to the Oxford English Dictionary middle age is between 45 and 65: "The period between early adulthood and old age, usually considered as the years from about 45 to 65."

The US Census lists the category middle age from 45 to 65. Merriam-Webster list middle age from 45 to 64, while prominent psychologist Erik Erikson saw it starting a little earlier and defines middle adulthood as between 40 and 65.