Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Labor

covers all forms and sectors of jobs, whether public or private,white collar or blue collar, full-time or part-time, and including management. Further, Labor covers unemployment (e.g., due to automation) and its solutions (e.g., vocational training programs, including government programs in cooperation with businesses to help re-train workers who lost their jobs).

Employment In the United States

YouTube Video: Try This! Working with Bureau of Labor Statistics Databases

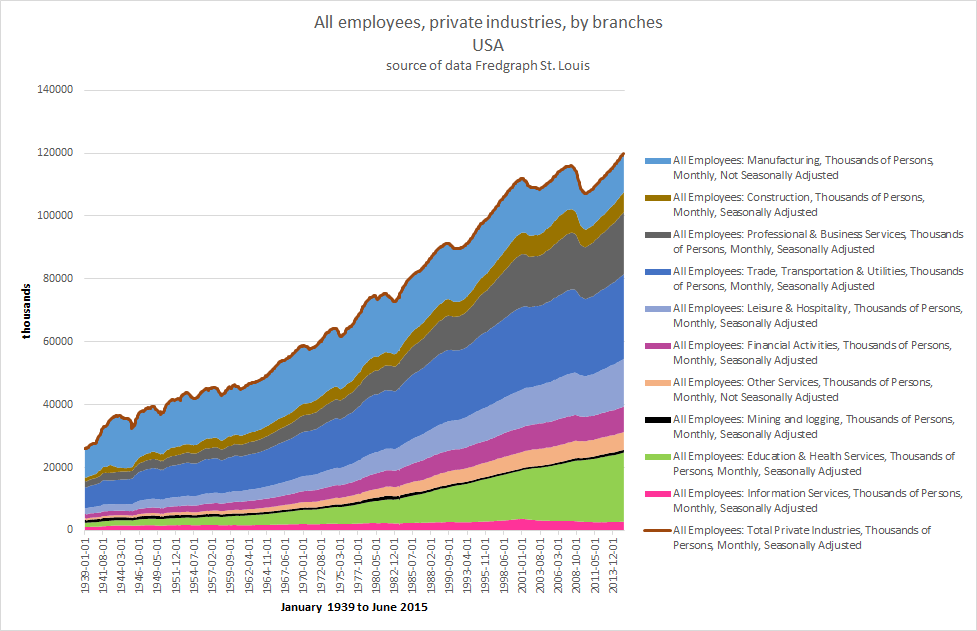

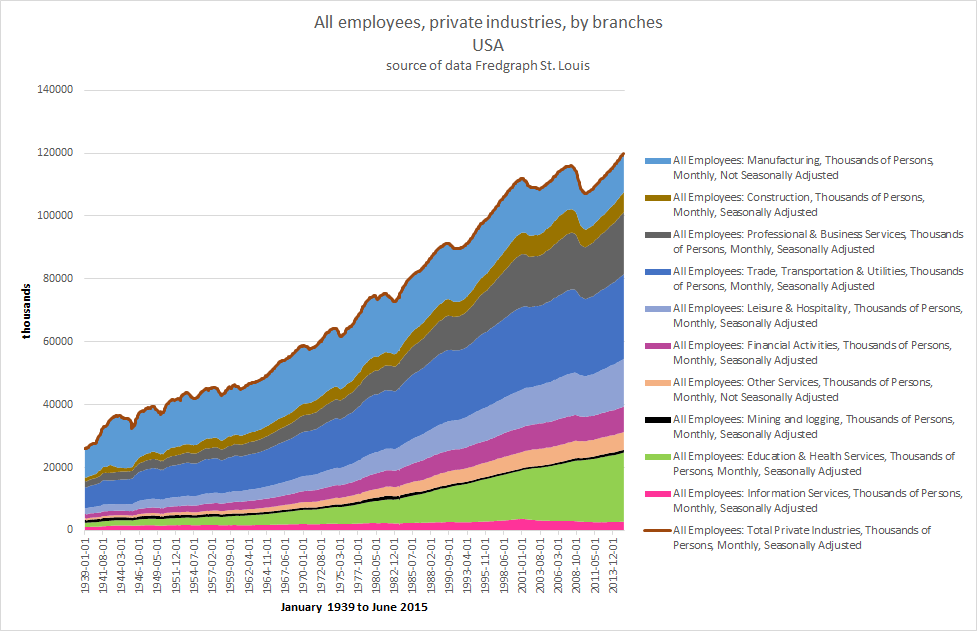

Pictured: Employment in the USA covering the Private Sector Jobs

Employment is a relationship between two parties, usually based on a contract where work is paid for, where one party, which may be a corporation, for profit, not-for-profit organization, co-operative or other entity is the employer and the other is the employee.

Employees work in return for payment, which may be in the form of an hourly wage, by piecework or an annual salary, depending on the type of work an employee does and/or which sector she or he is working in. Employees in some fields or sectors may receive gratuities, bonus payments or stock options.

In some types of employment, employees may receive benefits in addition to payment. Benefits can include health insurance, housing, disability insurance or use of a gym. Employment is typically governed by employment laws or regulations and/or legal contracts.

Employees and employers:

Further information: List of largest employers, List of professions, and Tradesman

An employee contributes labor and expertise to an endeavor of an employer or of a person conducting a business or undertaking and is usually hired to perform specific duties which are packaged into a job. In a corporate context, an employee is a person who is hired to provide services to a company on a regular basis in exchange for compensation and who does not provide these services as part of an independent business.

Employer-worker relationship:

Employer and managerial control within an organization rests at many levels and has important implications for staff and productivity alike, with control forming the fundamental link between desired outcomes and actual processes. Employers must balance interests such as decreasing wage constraints with a maximization of labor productivity in order to achieve a profitable and productive employment relationship.

Finding employees or employment:

The main ways for employers to find workers and for people to find employers are via jobs listings in newspapers (via classified advertising) and online, also called job boards. Employers and job seekers also often find each other via professional recruitment consultants which receive a commission from the employer to find, screen and select suitable candidates.

However, a study has shown that such consultants may not be reliable when they fail to use established principles in selecting employees. A more traditional approach is with a "Help Wanted" sign in the establishment (usually hung on a window or door or placed on a store counter).

Evaluating different employees can be quite laborious but setting up different techniques to analyze their skill to measure their talents within the field can be best through assessments. Employer and potential employee commonly take the additional step of getting to know each other through the process of job interview.

Training and development

This refers to the employer's effort to equip a newly hired employee with necessary skills to perform at the job, and to help the employee grow within the organization. An appropriate level of training and development helps to improve employee's job satisfaction.

Remuneration:

There are many ways that employees are paid, including by hourly wages, by piecework, by yearly salary, or by gratuities (with the latter often being combined with another form of payment.

In sales jobs and real estate positions, the employee may be paid a commission, a percentage of the value of the goods or services that they have sold.

In some fields and professions (e.g., executive jobs), employees may be eligible for a bonus if they meet certain targets. Some executives and employees may be paid in stocks or stock options, a compensation approach that has the added benefit, from the company's point of view, of helping to align the interests of the compensated individual with the performance of the company.

Employee benefits:

These are various non-wage compensation provided to employee in addition to their wages or salaries. The benefits can include:

In some cases, such as with workers employed in remote or isolated regions, the benefits may include meals. Employee benefits can improve the relationship between employee and employer and lowers staff turnover.

Organizational justice is an employee's perception and judgement of employer's treatment in the context of fairness or justice. The resulting actions to influence the employee-employer relationship is also a part of organizational justice.

Workforce organizing:

Employees can organize into trade or labor unions, which represent the work force to collectively bargain with the management of organizations about working, and contractual conditions and services.

Ending employment:

Usually, either an employee or employer may end the relationship at any time, often subject to a certain notice period. This is referred to as at-will employment. The contract between the two parties specifies the responsibilities of each when ending the relationship and may include requirements such as notice periods, severance pay, and security measures. In some professions, notably teaching, civil servants, university professors, and some orchestra jobs, some employees may have tenure, which means that they cannot be dismissed at will.

Wage Labor:

Wage labor is the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer, where the worker sells their labor under a formal or informal employment contract. These transactions usually occur in a labor market where wages are market determined. In exchange for the wages paid, the work product generally becomes the undifferentiated property of the employer, except for special cases such as the vesting of intellectual property patents in the United States where patent rights are usually vested in the original personal inventor.

A wage laborer is a person whose primary means of income is from the selling of his or her labor in this way. In modern mixed economies such as that of the OECD countries, it is currently the dominant form of work arrangement.

Although most work occurs following this structure, the wage work arrangements of CEOs, professional employees, and professional contract workers are sometimes conflated with class assignments, so that "wage labor" is considered to apply only to unskilled, semi-skilled or manual labor.

Employment contract:

In the United States, the standard employment relationship is considered to be at-will, meaning that the employer and employee are both free to terminate the employment at any time and for any cause, or for no cause at all.

However, if a termination of employment by the employer is deemed unjust by the employee, there can be legal recourse to challenge such a termination. Unjust termination may include termination due to discrimination because of an individual's race, national origin, sex or gender, pregnancy, age, physical or mental disability, religion, or military status.

Additional protections apply in some states, for instance in California unjust termination reasons include marital status, ancestry, sexual orientation or medical condition. Despite whatever agreement an employer makes with an employee for the employee's wages, an employee is entitled to certain minimum wages set by the federal government.

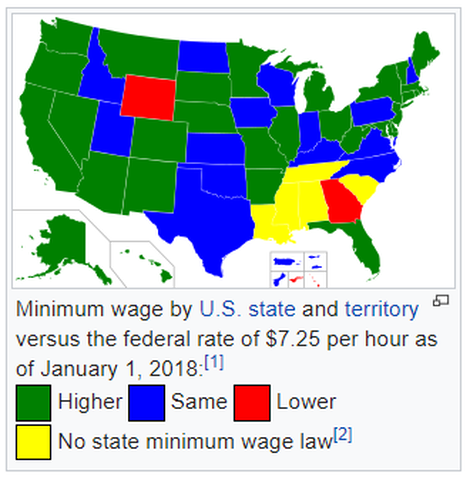

The states may set their own minimum wage that is higher than the federal government's to ensure a higher standard of living or living wage for those who are employed.

Under the Equal Pay Act of 1963, an employer may not give different wages based on sex alone.

Employees are often contrasted with independent contractors, especially when there is dispute as to the worker's entitlement to have matching taxes paid, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance benefits. However, in September 2009, the court case of Brown v. J. Kaz, Inc. ruled that independent contractors are regarded as employees for the purpose of discrimination laws if they work for the employer on a regular basis, and said employer directs the time, place, and manner of employment.

In non-union work environments, in the United States, unjust termination complaints can be brought to the United States Department of Labor.

U.S. Federal income tax withholding:

For purposes of U.S. federal income tax withholding, 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) provides a definition for the term "employee" specific to chapter 24 of the Internal Revenue Code:

"For purposes of this chapter, the term “employee” includes an officer, employee, or elected official of the United States, a State, or any political subdivision thereof, or the District of Columbia, or any agency or instrumentality of any one or more of the foregoing. The term “employee” also includes an officer of a corporation."

This definition does not exclude all those who are commonly known as 'employees'. “Similarly, Latham’s instruction which indicated that under 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) the category of ‘employee’ does not include privately employed wage earners is a preposterous reading of the statute. It is obvious that within the context of both statutes the word ‘includes’ is a term of enlargement not of limitation, and the reference to certain entities or categories is not intended to exclude all others.”

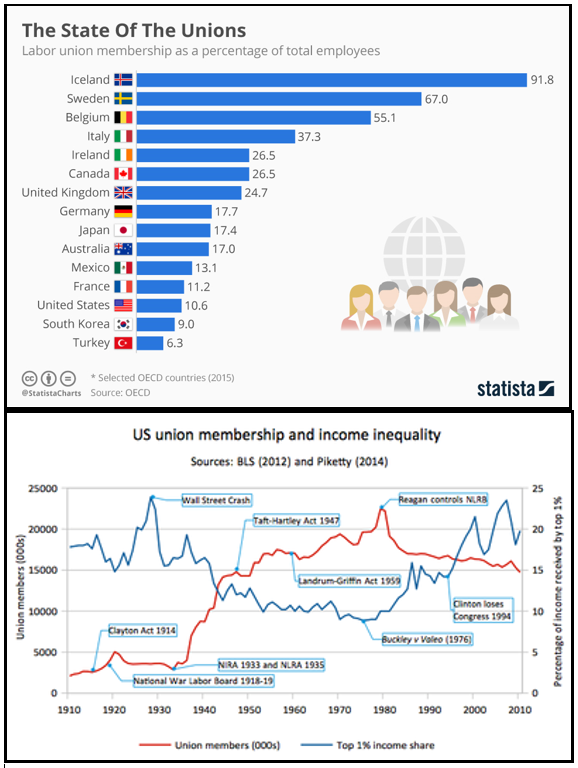

Labor Unions in The United States:

Labor unions are legally recognized as representatives of workers in many industries in the United States. Their activity today centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and electioneering at the state and federal level.

Most unions in America are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL-CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.

For further amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

Employees work in return for payment, which may be in the form of an hourly wage, by piecework or an annual salary, depending on the type of work an employee does and/or which sector she or he is working in. Employees in some fields or sectors may receive gratuities, bonus payments or stock options.

In some types of employment, employees may receive benefits in addition to payment. Benefits can include health insurance, housing, disability insurance or use of a gym. Employment is typically governed by employment laws or regulations and/or legal contracts.

Employees and employers:

Further information: List of largest employers, List of professions, and Tradesman

An employee contributes labor and expertise to an endeavor of an employer or of a person conducting a business or undertaking and is usually hired to perform specific duties which are packaged into a job. In a corporate context, an employee is a person who is hired to provide services to a company on a regular basis in exchange for compensation and who does not provide these services as part of an independent business.

Employer-worker relationship:

Employer and managerial control within an organization rests at many levels and has important implications for staff and productivity alike, with control forming the fundamental link between desired outcomes and actual processes. Employers must balance interests such as decreasing wage constraints with a maximization of labor productivity in order to achieve a profitable and productive employment relationship.

Finding employees or employment:

The main ways for employers to find workers and for people to find employers are via jobs listings in newspapers (via classified advertising) and online, also called job boards. Employers and job seekers also often find each other via professional recruitment consultants which receive a commission from the employer to find, screen and select suitable candidates.

However, a study has shown that such consultants may not be reliable when they fail to use established principles in selecting employees. A more traditional approach is with a "Help Wanted" sign in the establishment (usually hung on a window or door or placed on a store counter).

Evaluating different employees can be quite laborious but setting up different techniques to analyze their skill to measure their talents within the field can be best through assessments. Employer and potential employee commonly take the additional step of getting to know each other through the process of job interview.

Training and development

This refers to the employer's effort to equip a newly hired employee with necessary skills to perform at the job, and to help the employee grow within the organization. An appropriate level of training and development helps to improve employee's job satisfaction.

Remuneration:

There are many ways that employees are paid, including by hourly wages, by piecework, by yearly salary, or by gratuities (with the latter often being combined with another form of payment.

In sales jobs and real estate positions, the employee may be paid a commission, a percentage of the value of the goods or services that they have sold.

In some fields and professions (e.g., executive jobs), employees may be eligible for a bonus if they meet certain targets. Some executives and employees may be paid in stocks or stock options, a compensation approach that has the added benefit, from the company's point of view, of helping to align the interests of the compensated individual with the performance of the company.

Employee benefits:

These are various non-wage compensation provided to employee in addition to their wages or salaries. The benefits can include:

- housing (employer-provided or employer-paid),

- group insurance (health, dental, life etc.),

- disability income protection,

- retirement benefits,

- daycare,

- tuition reimbursement,

- sick leave,

- vacation (paid and non-paid),

- social security,

- profit sharing,

- funding of education,

- and other specialized benefits.

In some cases, such as with workers employed in remote or isolated regions, the benefits may include meals. Employee benefits can improve the relationship between employee and employer and lowers staff turnover.

Organizational justice is an employee's perception and judgement of employer's treatment in the context of fairness or justice. The resulting actions to influence the employee-employer relationship is also a part of organizational justice.

Workforce organizing:

Employees can organize into trade or labor unions, which represent the work force to collectively bargain with the management of organizations about working, and contractual conditions and services.

Ending employment:

Usually, either an employee or employer may end the relationship at any time, often subject to a certain notice period. This is referred to as at-will employment. The contract between the two parties specifies the responsibilities of each when ending the relationship and may include requirements such as notice periods, severance pay, and security measures. In some professions, notably teaching, civil servants, university professors, and some orchestra jobs, some employees may have tenure, which means that they cannot be dismissed at will.

Wage Labor:

Wage labor is the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer, where the worker sells their labor under a formal or informal employment contract. These transactions usually occur in a labor market where wages are market determined. In exchange for the wages paid, the work product generally becomes the undifferentiated property of the employer, except for special cases such as the vesting of intellectual property patents in the United States where patent rights are usually vested in the original personal inventor.

A wage laborer is a person whose primary means of income is from the selling of his or her labor in this way. In modern mixed economies such as that of the OECD countries, it is currently the dominant form of work arrangement.

Although most work occurs following this structure, the wage work arrangements of CEOs, professional employees, and professional contract workers are sometimes conflated with class assignments, so that "wage labor" is considered to apply only to unskilled, semi-skilled or manual labor.

Employment contract:

In the United States, the standard employment relationship is considered to be at-will, meaning that the employer and employee are both free to terminate the employment at any time and for any cause, or for no cause at all.

However, if a termination of employment by the employer is deemed unjust by the employee, there can be legal recourse to challenge such a termination. Unjust termination may include termination due to discrimination because of an individual's race, national origin, sex or gender, pregnancy, age, physical or mental disability, religion, or military status.

Additional protections apply in some states, for instance in California unjust termination reasons include marital status, ancestry, sexual orientation or medical condition. Despite whatever agreement an employer makes with an employee for the employee's wages, an employee is entitled to certain minimum wages set by the federal government.

The states may set their own minimum wage that is higher than the federal government's to ensure a higher standard of living or living wage for those who are employed.

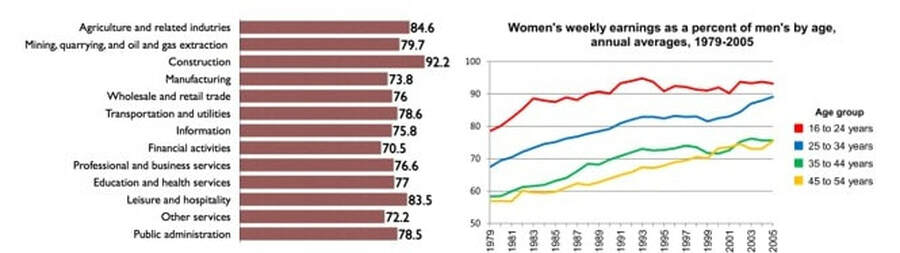

Under the Equal Pay Act of 1963, an employer may not give different wages based on sex alone.

Employees are often contrasted with independent contractors, especially when there is dispute as to the worker's entitlement to have matching taxes paid, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance benefits. However, in September 2009, the court case of Brown v. J. Kaz, Inc. ruled that independent contractors are regarded as employees for the purpose of discrimination laws if they work for the employer on a regular basis, and said employer directs the time, place, and manner of employment.

In non-union work environments, in the United States, unjust termination complaints can be brought to the United States Department of Labor.

U.S. Federal income tax withholding:

For purposes of U.S. federal income tax withholding, 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) provides a definition for the term "employee" specific to chapter 24 of the Internal Revenue Code:

"For purposes of this chapter, the term “employee” includes an officer, employee, or elected official of the United States, a State, or any political subdivision thereof, or the District of Columbia, or any agency or instrumentality of any one or more of the foregoing. The term “employee” also includes an officer of a corporation."

This definition does not exclude all those who are commonly known as 'employees'. “Similarly, Latham’s instruction which indicated that under 26 U.S.C. § 3401(c) the category of ‘employee’ does not include privately employed wage earners is a preposterous reading of the statute. It is obvious that within the context of both statutes the word ‘includes’ is a term of enlargement not of limitation, and the reference to certain entities or categories is not intended to exclude all others.”

Labor Unions in The United States:

Labor unions are legally recognized as representatives of workers in many industries in the United States. Their activity today centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and electioneering at the state and federal level.

Most unions in America are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL-CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.

For further amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

- Age-related issues

- Working poor

- Models of the employment relationship

- Academic literature

- Globalization and employment relations

- Alternatives

- See also

- Notes and references

- Bibliography

- External links

Unemployment in the United States and its Causes, along with eligibility to realize unemployment benefits through the Federal Unemployment Insurance Program.

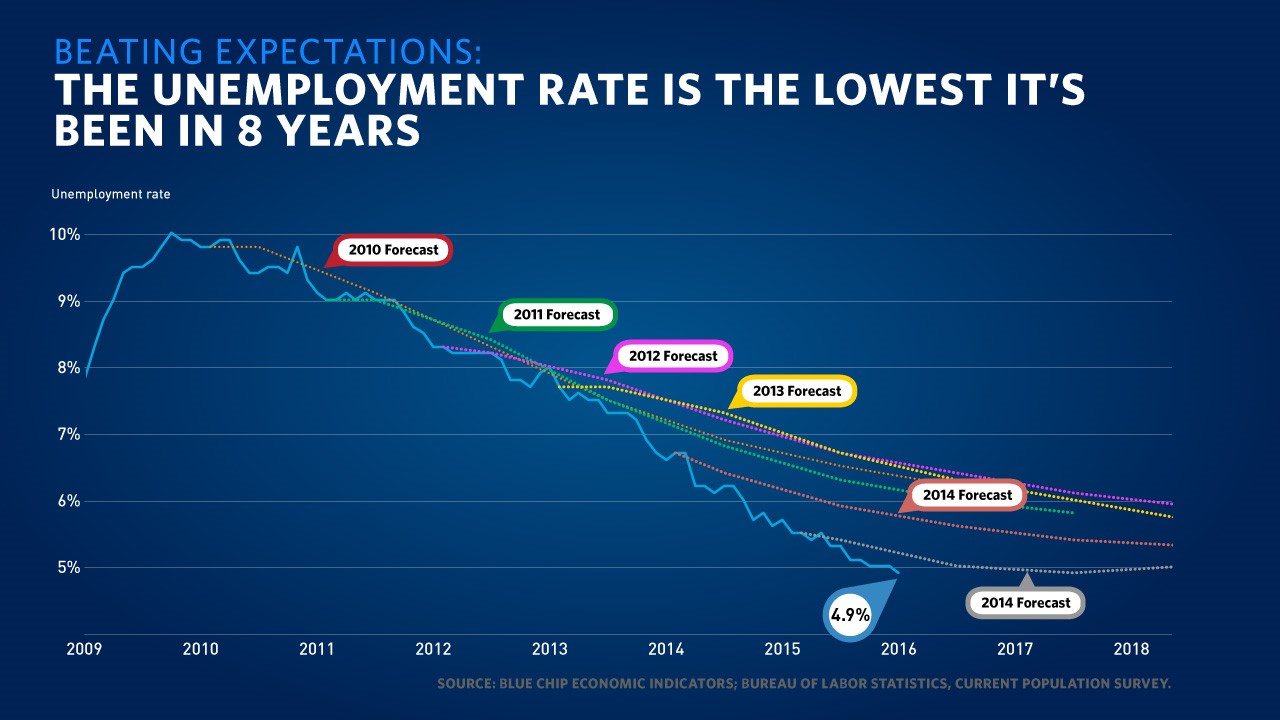

Pictured below: Graph illustrating that increased job growth has lowered the unemployment rate fron 10% in 2010 to 4.9% through 2014

- YouTube Video: President Obama Speaks on the Economy 2/5/16 that unemployment has dropped to 4.9%.

- YouTube Video: Asking Robert Reich* about Technological Unemployment and Unconditional Basic Income

Pictured below: Graph illustrating that increased job growth has lowered the unemployment rate fron 10% in 2010 to 4.9% through 2014

Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes and measures of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

Unemployment generally falls during periods of economic prosperity and rises during recessions, creating significant pressure on public finances as tax revenue falls and social safety net costs increase.

For example, employment expanded consistently during the 1990s, but has been inconsistent since due to recessions in 2001 and 2007-2009. As of May 2016, the employment recovery relative to the December 2007 (pre-recession) level was mixed.

Variables such as the unemployment rate (U-3) and number of employed have improved beyond their pre-recession levels. However, the wider U-6 unemployment rate, measures of labor force participation (even among the prime working age group), and the share of long-term unemployed were worse than pre-crisis levels. Further, the mix of jobs has shifted, with a larger share of part-time workers than pre-crisis.

Government spending and taxation decisions (fiscal policy) and U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate adjustments (monetary policy) are important tools for managing the unemployment rate.

There may be an economic trade-off between unemployment and inflation, as policies designed to reduce unemployment can create inflationary pressure, and vice versa. The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) has a dual mandate to achieve full employment while maintaining a low rate of inflation.

Debates regarding monetary policy during 2014-2015 centered on the timing and extent of interest rate increases, as a near-zero interest rate target had remained in place since the 2007-2009 recession. Ultimately, the Fed decided to raise interest rates marginally in December 2015.

The major political parties debate appropriate solutions for improving the job creation rate, with liberals arguing for more government spending and conservatives arguing for lower taxes and less regulation.

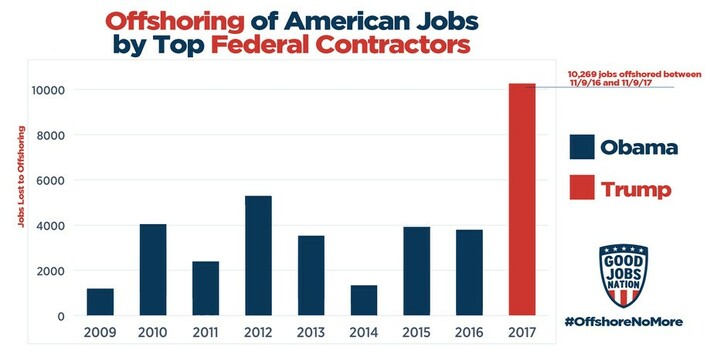

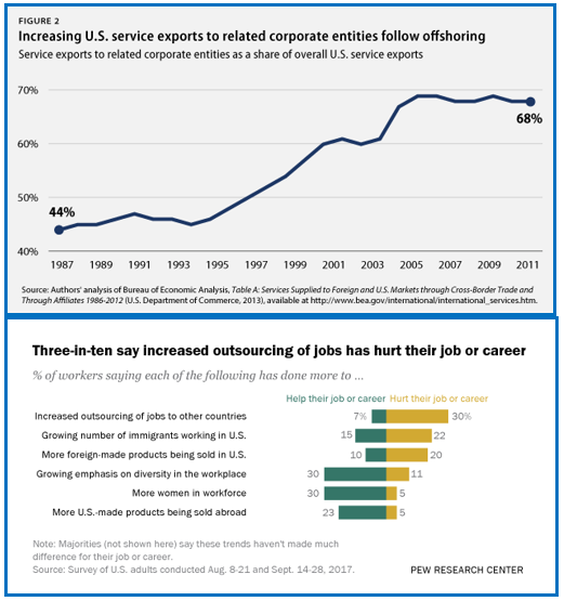

Polls indicate that Americans believe job creation is the most important government priority, with not sending jobs overseas the primary solution. Much of the 2012 Presidential campaign focused on job creation as a first priority, but the fiscal cliff and other fiscal debates took precedence in 2012 and early 2013.

Critics argued prioritizing deficit reduction was misplaced, as there was no immediate fiscal crisis but there was a high level of unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment.

Unemployment can be measured in several ways. A person is unemployed if they are jobless but looking for a job and available for work. People who are neither employed nor unemployed are not in the labor force.

For example, as of December 2015, the unemployment rate in the United States was 5.0% or 7.9 million people, while the government's broader U-6 unemployment rate, which includes the part-time underemployed was 9.9% or approximately 16.4 million people.

These figures were calculated with a civilian labor force of approximately 157.8 million people, relative to a U.S. population of approximately 323 million people. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes a monthly "Employment Situation Summary" with key statistics and commentary.

In 2014, Williams County, North Dakota had the lowest percentage of unemployed people of any county or census area in the United States, at 1.2 percent, while Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska had the highest, at 23.7 percent.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

Causes of Unemployment in the United States

Causes of Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for amplification:

Unemployment generally falls during periods of economic prosperity and rises during recessions, creating significant pressure on public finances as tax revenue falls and social safety net costs increase.

For example, employment expanded consistently during the 1990s, but has been inconsistent since due to recessions in 2001 and 2007-2009. As of May 2016, the employment recovery relative to the December 2007 (pre-recession) level was mixed.

Variables such as the unemployment rate (U-3) and number of employed have improved beyond their pre-recession levels. However, the wider U-6 unemployment rate, measures of labor force participation (even among the prime working age group), and the share of long-term unemployed were worse than pre-crisis levels. Further, the mix of jobs has shifted, with a larger share of part-time workers than pre-crisis.

Government spending and taxation decisions (fiscal policy) and U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate adjustments (monetary policy) are important tools for managing the unemployment rate.

There may be an economic trade-off between unemployment and inflation, as policies designed to reduce unemployment can create inflationary pressure, and vice versa. The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) has a dual mandate to achieve full employment while maintaining a low rate of inflation.

Debates regarding monetary policy during 2014-2015 centered on the timing and extent of interest rate increases, as a near-zero interest rate target had remained in place since the 2007-2009 recession. Ultimately, the Fed decided to raise interest rates marginally in December 2015.

The major political parties debate appropriate solutions for improving the job creation rate, with liberals arguing for more government spending and conservatives arguing for lower taxes and less regulation.

Polls indicate that Americans believe job creation is the most important government priority, with not sending jobs overseas the primary solution. Much of the 2012 Presidential campaign focused on job creation as a first priority, but the fiscal cliff and other fiscal debates took precedence in 2012 and early 2013.

Critics argued prioritizing deficit reduction was misplaced, as there was no immediate fiscal crisis but there was a high level of unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment.

Unemployment can be measured in several ways. A person is unemployed if they are jobless but looking for a job and available for work. People who are neither employed nor unemployed are not in the labor force.

For example, as of December 2015, the unemployment rate in the United States was 5.0% or 7.9 million people, while the government's broader U-6 unemployment rate, which includes the part-time underemployed was 9.9% or approximately 16.4 million people.

These figures were calculated with a civilian labor force of approximately 157.8 million people, relative to a U.S. population of approximately 323 million people. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes a monthly "Employment Situation Summary" with key statistics and commentary.

In 2014, Williams County, North Dakota had the lowest percentage of unemployed people of any county or census area in the United States, at 1.2 percent, while Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska had the highest, at 23.7 percent.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

- Definitions of unemployment

- U.S. employment history: Jobs created by Presidential term

- Recent employment trends

- Causes of unemployment

- Fiscal and monetary policy

- Political debates

- Solutions for creating more U.S. jobs

- Analytical perspectives

- Labor market recovery following 2007-2009 recession

- Comparison of employment recovery across recessions and financial crises

- Share of full-time and part-time workers

- What job creation rate is required to lower the unemployment rate?

- International labor force size comparisons

- Effect of disability recipients on labor force participation measures

- Effects on health and mortality

- Effects of healthcare reform

- Job growth projections 2014-2024

- Obtaining data

- Historical unemployment rate charts

- See also:

Causes of Unemployment in the United States

Causes of Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for amplification:

- Overview

- Domestic factors

- Cyclical vs. structural unemployment

- Demographics and labor force participation rate

- Education and training

- Skills gap

- Long-term unemployment

- Labor unions

- Industry consolidation

- Income and wealth inequality

- Government hiring trends

- Policies regarding full employment

- Unemployment among younger workers

- Job openings relative to unemployed

- Trends in alternative (part-time) work arrangements

- Global factors

- Automation and technology change

- The "Access" or "On Demand" economy

- Immigration

- Trade deals -- NAFTA

- Other factors

The Labor force in the United States

YouTube Video of "The Great Divide" with Joseph Stiglitz and Robert Reich

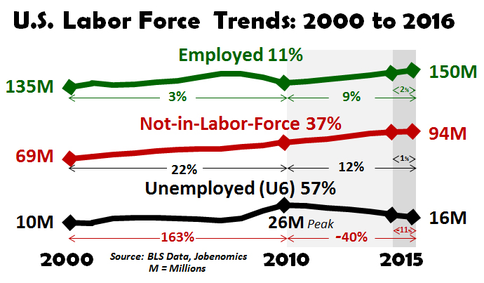

Pictured: U.S. Labor Trends from 2000 to 2016 (BLS)

The labor force is the actual number of people available for work. The labor force of a country includes both the employed and the unemployed. The labor force participation rate, LFPR (or economic activity rate, EAR), is the ratio between the labor force and the overall size of their cohort (national population of the same age range).

The unemployment rate in the United States is estimated by a household survey called the Current Population Survey, conducted monthly by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed persons by the size of the workforce and multiplying that number by 100, where an unemployed person is defined as a person not currently employed but actively seeking work. The size of the workforce is defined as those employed plus those unemployed.

By BLS definitions, the labor force is the following: "Included are persons 16 years of age and older residing in the 50 States and the District of Columbia who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities, homes for the aged), and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces."

The labor force participation rate is the ratio between the labor force and the overall size of their cohort (national population of the same age range). In the West during the later half of the 20th century, the labor force participation rate increased significantly, largely due to the increasing number of women entering the workplace.

Gender and the United States Work Force:

In the United States, there were three significant stages of women’s increased participation in the labor force. During the late 19th century through the 1920s, very few women worked.

Working women were often young single women who typically withdrew from labor force at marriage unless their family needed two incomes. These women worked primarily in the textile manufacturing industry or as domestic workers. This profession empowered women and allowed them to earn a living wage. At times, they were a financial help to their families.

Between 1930 and 1950, female labor force participation increased primarily due to the increased demand for office workers, women participating in the high school movement, and electrification which reduced the time spent on household chores. In the 1950s to the 1970s, most women were secondary earners working mainly as secretaries, teachers, nurses, and librarians (pink-collar jobs).

Claudia Goldin and others, specifically point out that by the mid-1970s there was a period of revolution of women in the labor force brought on by different factors. Women more accurately planned for their future in the work force, choosing more applicable majors in college that prepared them to enter and compete in the labor market. In the United States, the labor force participation rate rose from approximately 59% in 1948 to 66% in 2005, with participation among women rising from 32% to 59% and participation among men declining from 87% to 73%.

A common theory in modern economics claims that the rise of women participating in the US labor force in the late 1960s was due to the introduction of a new contraceptive technology, birth control pills, and the adjustment of age of majority laws. The use of birth control gave women the flexibility of opting to invest and advance their career while maintaining a relationship.

By having control over the timing of their fertility, they were not running a risk of thwarting their career choices. However, only 40% of the population actually used the birth control pill. This implies that other factors may have contributed to women choosing to invest in advancing their careers.

Another factor that may have contributed to the trend was the The Equal Pay Act of 1963, which aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex. Such legislation diminished sexual discrimination and encouraged more women to enter the labor market by receiving fair remuneration to help raise children.

The labor force participation rate can decrease when the rate of growth of the population outweighs that of the employed and unemployed together. The labor force participation rate is a key component in long-term economic growth, almost as important as productivity.

The labor force participation rate explains how an increase in the unemployment rate can occur simultaneously with an increase in employment. If a large amount of new workers enter the labor force but only a small fraction become employed, then the increase in the number of unemployed workers can outpace the growth in employment

See Also:

The unemployment rate in the United States is estimated by a household survey called the Current Population Survey, conducted monthly by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed persons by the size of the workforce and multiplying that number by 100, where an unemployed person is defined as a person not currently employed but actively seeking work. The size of the workforce is defined as those employed plus those unemployed.

By BLS definitions, the labor force is the following: "Included are persons 16 years of age and older residing in the 50 States and the District of Columbia who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities, homes for the aged), and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces."

The labor force participation rate is the ratio between the labor force and the overall size of their cohort (national population of the same age range). In the West during the later half of the 20th century, the labor force participation rate increased significantly, largely due to the increasing number of women entering the workplace.

Gender and the United States Work Force:

In the United States, there were three significant stages of women’s increased participation in the labor force. During the late 19th century through the 1920s, very few women worked.

Working women were often young single women who typically withdrew from labor force at marriage unless their family needed two incomes. These women worked primarily in the textile manufacturing industry or as domestic workers. This profession empowered women and allowed them to earn a living wage. At times, they were a financial help to their families.

Between 1930 and 1950, female labor force participation increased primarily due to the increased demand for office workers, women participating in the high school movement, and electrification which reduced the time spent on household chores. In the 1950s to the 1970s, most women were secondary earners working mainly as secretaries, teachers, nurses, and librarians (pink-collar jobs).

Claudia Goldin and others, specifically point out that by the mid-1970s there was a period of revolution of women in the labor force brought on by different factors. Women more accurately planned for their future in the work force, choosing more applicable majors in college that prepared them to enter and compete in the labor market. In the United States, the labor force participation rate rose from approximately 59% in 1948 to 66% in 2005, with participation among women rising from 32% to 59% and participation among men declining from 87% to 73%.

A common theory in modern economics claims that the rise of women participating in the US labor force in the late 1960s was due to the introduction of a new contraceptive technology, birth control pills, and the adjustment of age of majority laws. The use of birth control gave women the flexibility of opting to invest and advance their career while maintaining a relationship.

By having control over the timing of their fertility, they were not running a risk of thwarting their career choices. However, only 40% of the population actually used the birth control pill. This implies that other factors may have contributed to women choosing to invest in advancing their careers.

Another factor that may have contributed to the trend was the The Equal Pay Act of 1963, which aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex. Such legislation diminished sexual discrimination and encouraged more women to enter the labor market by receiving fair remuneration to help raise children.

The labor force participation rate can decrease when the rate of growth of the population outweighs that of the employed and unemployed together. The labor force participation rate is a key component in long-term economic growth, almost as important as productivity.

The labor force participation rate explains how an increase in the unemployment rate can occur simultaneously with an increase in employment. If a large amount of new workers enter the labor force but only a small fraction become employed, then the increase in the number of unemployed workers can outpace the growth in employment

See Also:

- Workforce

- Unemployment

- Employment-to-population ratio

- List of countries by labor force

- Proletariat

- Feminization of poverty

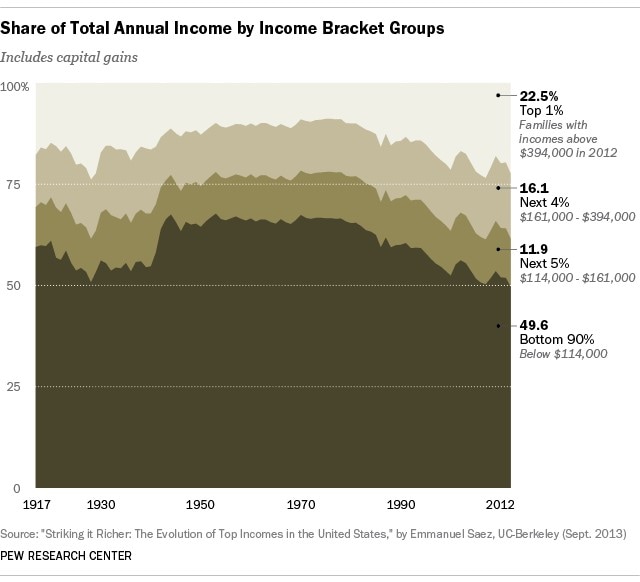

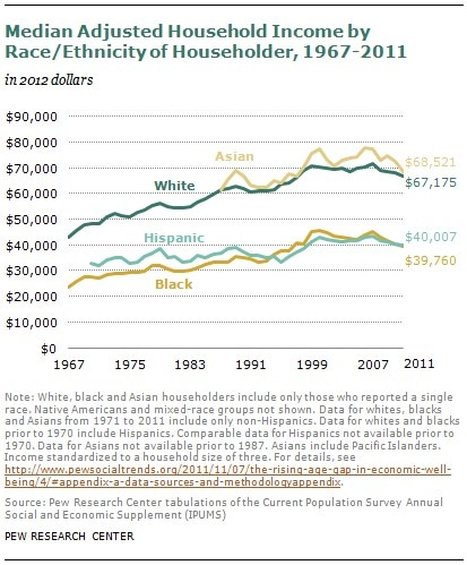

Five Facts about Income Inequality by PEW Research Center (1/7/2014)

Fact #1: By one measure, U.S. income inequality is the highest it’s been since 1928.

In 1982, the highest-earning 1% of families received 10.8% of all pretax income, while the bottom 90% received 64.7%, according to research by UC-Berkeley professor Emmanuel Saez. Three decades later, according to Saez’ preliminary estimates for 2012, the top 1% received 22.5% of pretax income, while the bottom 90%’s share had fallen to 49.6%.

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Fact #2: The U.S. is more unequal than most of its developed-world peers. According to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. ranked 10th out of 31 OECD countries in income inequality based on “market incomes” — that is, before taking into account the redistributive effects of tax policies and income-transfer programs such as Social Security and unemployment insurance. After accounting for taxes and transfers, the U.S. had the second-highest level of inequality, after Chile.

___________________________________________________________________________

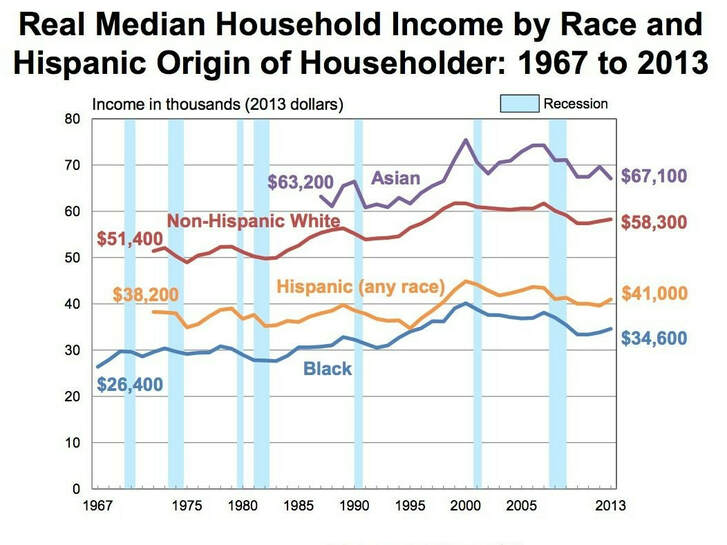

Fact #3: The black-white income gap in the U.S. has persisted. The difference in median household incomes between whites and blacks has grown from about $19,000 in 1967 to roughly $27,000 in 2011 (as measured in 2012 dollars). Median black household income was 59% of median white household income in 2011, up modestly from 55% in 1967; as recently as 2007, black income was 63% of white income.

Fact #4: Americans are relatively unconcerned about the wide income gap between rich and poor. Americans in the upper fifth of the income distribution earn 16.7 times as much as those in the lowest fifth — by far the widest such gap among the 10 advanced countries in the Pew Research Center’s 2013 global attitudes survey. Yet barely half (47%) of Americans think the rich-poor gap is a very big problem. Among advanced countries, only Australians expressed a lower level of concern, but in Australia the top fifth earned just 2.7 times the income of the bottom fifth.

___________________________________________________________________________

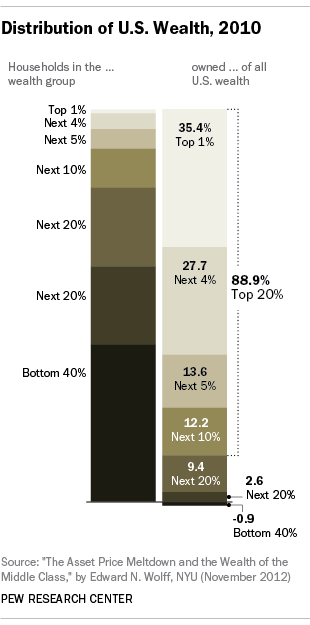

Fact #5: Wealth inequality is even greater than income inequality. NYU economist Edward Wolff has found that, while the highest-earning fifth of U.S. families earned 59.1% of all income, the richest fifth held 88.9% of all wealth.

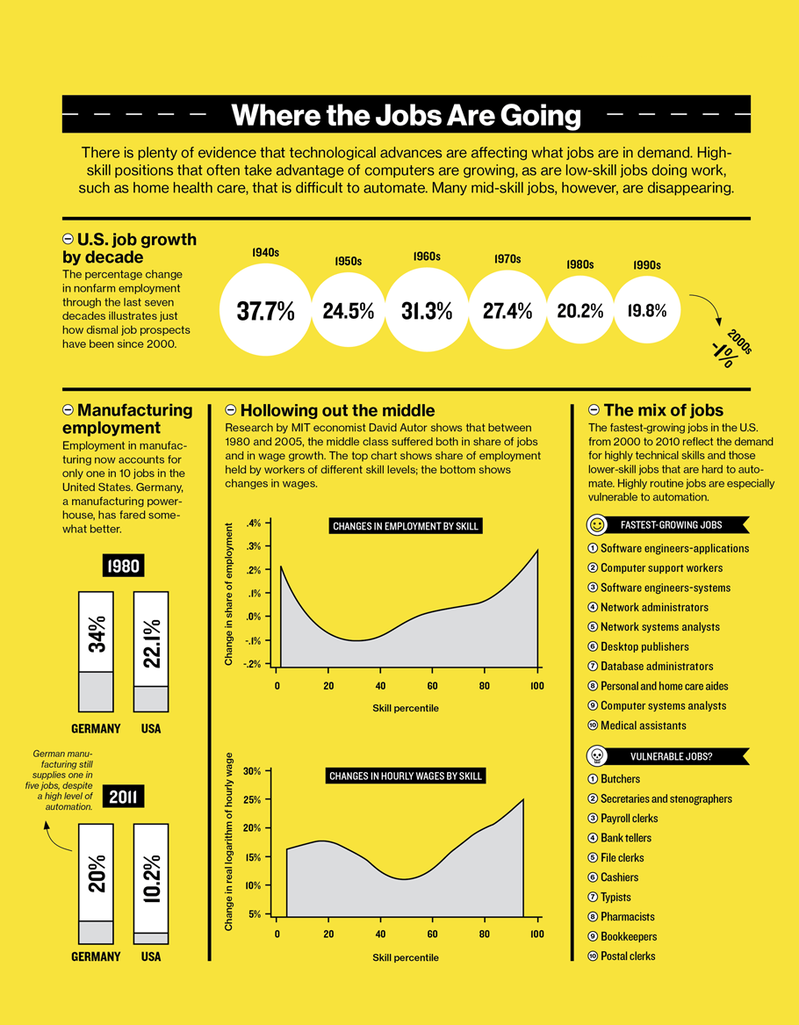

The Negative Impact of Technology on Jobs

YouTube Video: Top 10 Jobs Most Likely to be Replaced by Robots by WatchMojo

Pictured: In the 21st century, robots are beginning to perform roles not just in industry, but in the service sector, working as entertainers and careers. (Courtesy of jk (talk) - self-made, CC BY 3.0)

Unemployment created by Automation Technology is the loss of jobs caused by technological change. Such change typically includes the introduction of labour-saving "mechanical-muscle" machines or more efficient "mechanical-mind" processes (automation).

Just as horses employed as prime movers were gradually made obsolete by the automobile, humans' jobs have also been affected throughout modern history. Historical examples include artisan weavers reduced to poverty after the introduction of mechanized looms.

During World War II, Alan Turing's Bombe machine compressed and decoded thousands of man-years worth of encrypted data in a matter of hours.

A contemporary example of technological unemployment is the displacement of retail cashiers by self-service tills.

That technological change can cause short-term job losses is widely accepted. The view that it can lead to lasting increases in unemployment has long been controversial. Participants in the technological unemployment debates can be broadly divided into optimists and pessimists. Optimists agree that innovation may be disruptive to jobs in the short term, yet hold that various compensation effects ensure there is never a long-term negative impact on jobs.

Whereas pessimists contend that at least in some circumstances, new technologies can lead to a lasting decline in the total number of workers in employment. The phrase "technological unemployment" was popularised by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s. Yet the issue of machines displacing human labour has been discussed since at least Aristotle's time.

Prior to the 18th century both the elite and ordinary people would generally take the pessimistic view on technological unemployment, at least in cases where the issue arose. Due to generally low unemployment in much of pre-modern history, the topic was rarely a prominent concern.

In the 18th century fears over the impact of machinery on jobs intensified with the growth of mass unemployment, especially in Great Britain which was then at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution.

Yet some economic thinkers began to argue against these fears, claiming that overall innovation would not have negative effects on jobs. These arguments were formalised in the early 19th century by the classical economists. During the second half of the 19th century, it became increasingly apparent that technological progress was benefiting all sections of society, including the working class. Concerns over the negative impact of innovation diminished. The term "Luddite fallacy" was coined to describe the thinking that innovation would have lasting harmful effects on employment.

The view that technology is unlikely to lead to long term unemployment has been repeatedly challenged by a minority of economists. In the early 1800s these included Ricardo himself.

There were dozens of economists warning about technological unemployment during brief intensification of the debate that spiked in the 1930s and 1960s. Especially in Europe, there were further warnings in the closing two decades of the twentieth century, as commentators noted an enduring rise in unemployment suffered by many industrialised nations since the 1970s.

Yet a clear majority of both professional economists and the interested general public held the optimistic view through most of the 20th century.

In the second decade of the 21st century, a number of studies have been released suggesting that technological unemployment may be increasing worldwide. Further increases are forecast for the years to come.

While many economists and commentators still argue such fears are unfounded, as was widely accepted for most of the previous two centuries, concern over technological unemployment is growing once again. A report in Wired in 2017 quotes knowledgeable people such as economist Gene Sperling and management professor Andrew McAfee on the idea that handling existing and impending job loss to automation is a "significant issue".

Regarding a recent claim by a political appointee that automation is not “going to have any kind of big effect on the economy for the next 50 or 100 years,” says McAfee, “I don’t talk to anyone in the field who believes that.” Innovations like IBM's Watson have the potential to render humans obsolete with the professional, white-collar, low-skilled, creative fields, and other "mental jobs".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Unemployment created by Automation Technology:

Just as horses employed as prime movers were gradually made obsolete by the automobile, humans' jobs have also been affected throughout modern history. Historical examples include artisan weavers reduced to poverty after the introduction of mechanized looms.

During World War II, Alan Turing's Bombe machine compressed and decoded thousands of man-years worth of encrypted data in a matter of hours.

A contemporary example of technological unemployment is the displacement of retail cashiers by self-service tills.

That technological change can cause short-term job losses is widely accepted. The view that it can lead to lasting increases in unemployment has long been controversial. Participants in the technological unemployment debates can be broadly divided into optimists and pessimists. Optimists agree that innovation may be disruptive to jobs in the short term, yet hold that various compensation effects ensure there is never a long-term negative impact on jobs.

Whereas pessimists contend that at least in some circumstances, new technologies can lead to a lasting decline in the total number of workers in employment. The phrase "technological unemployment" was popularised by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s. Yet the issue of machines displacing human labour has been discussed since at least Aristotle's time.

Prior to the 18th century both the elite and ordinary people would generally take the pessimistic view on technological unemployment, at least in cases where the issue arose. Due to generally low unemployment in much of pre-modern history, the topic was rarely a prominent concern.

In the 18th century fears over the impact of machinery on jobs intensified with the growth of mass unemployment, especially in Great Britain which was then at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution.

Yet some economic thinkers began to argue against these fears, claiming that overall innovation would not have negative effects on jobs. These arguments were formalised in the early 19th century by the classical economists. During the second half of the 19th century, it became increasingly apparent that technological progress was benefiting all sections of society, including the working class. Concerns over the negative impact of innovation diminished. The term "Luddite fallacy" was coined to describe the thinking that innovation would have lasting harmful effects on employment.

The view that technology is unlikely to lead to long term unemployment has been repeatedly challenged by a minority of economists. In the early 1800s these included Ricardo himself.

There were dozens of economists warning about technological unemployment during brief intensification of the debate that spiked in the 1930s and 1960s. Especially in Europe, there were further warnings in the closing two decades of the twentieth century, as commentators noted an enduring rise in unemployment suffered by many industrialised nations since the 1970s.

Yet a clear majority of both professional economists and the interested general public held the optimistic view through most of the 20th century.

In the second decade of the 21st century, a number of studies have been released suggesting that technological unemployment may be increasing worldwide. Further increases are forecast for the years to come.

While many economists and commentators still argue such fears are unfounded, as was widely accepted for most of the previous two centuries, concern over technological unemployment is growing once again. A report in Wired in 2017 quotes knowledgeable people such as economist Gene Sperling and management professor Andrew McAfee on the idea that handling existing and impending job loss to automation is a "significant issue".

Regarding a recent claim by a political appointee that automation is not “going to have any kind of big effect on the economy for the next 50 or 100 years,” says McAfee, “I don’t talk to anyone in the field who believes that.” Innovations like IBM's Watson have the potential to render humans obsolete with the professional, white-collar, low-skilled, creative fields, and other "mental jobs".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Unemployment created by Automation Technology:

Designation of Workers by Collar Color, including:

- White Collar Workers,

- Blue Collar Workers,

- Pink Collar Workers,

- Gold Collar Workers,

- Grey Collar Workers,

- Green Collar Workers,

- The Ten Most Stressful White Collar Jobs

- Blue Collar Jobs are on the Decline

- More Men Entering "Pink Collar Jobs"

- What is a Gold-collar Worker?

- Grey Collar Workers: Paramedics: Emergency Response - Dangers of the Job

- Green Collar Jobs: Helping WWF create a sustainable workspace for the future

Designation of Workers by Collar Color:

Groups of working individuals are typically classified based on the colors of their collars worn at work; these can commonly reflect one's occupation or sometimes gender:

White Collar Workers:

In many countries (such as Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and United States), a white-collar worker is a person who performs professional, managerial, or administrative work.

White-collar work may be performed in an office or other administrative setting. Other types of work are those of a blue-collar worker, whose job requires manual labor and a pink-collar worker, whose labor is related to customer interaction, entertainment, sales, or other service-oriented work. Many occupations blend blue, white and pink (service) industry categorizations.

The term refers to the white dress shirts of male office workers common through most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Western countries, as opposed to the blue overalls worn by many manual laborers.

The term "white collar" is credited to Upton Sinclair, an American writer, in relation to contemporary clerical, administrative, and management workers during the 1930s, though references to white-collar work appear as early as 1935.

Demographics:

Formerly a minority in the agrarian and early industrial societies, white-collar workers have become a majority in industrialized countries due to modernization and outsourcing of manufacturing jobs.

The blue-collar and white-collar descriptors as it pertains to work dress may no longer be an accurate descriptor as office attire has broadened beyond a white shirt and tie. Employees in office environments may wear a variety of colors, may dress business casual or wear casual clothes altogether.

In addition work tasks have blurred. "White-collar" employees may perform "blue-collar" tasks (or vice versa). An example would be a restaurant manager who may wear more formal clothing yet still assist with cooking food or taking customers' orders or a construction worker who also performs desk work.

Health Effects:

Less physical activity among white-collar workers has been thought to be a key factor in increased life-style related health conditions such as:

Workplace interventions such as alternative activity workstations, sit-stand desks, promotion of stair use are among measures being implemented to counter the harms of sedentary workplace environments.

A Cochrane systematic review published in 2018 concluded that "At present there is low-quality evidence that the use of sit-stand desks reduce workplace sitting." Also, evidence was lacking on the long term health benefits of such interventions.

See also: ___________________________________________________________________________

Blue-Collar Worker:

In many countries, a blue-collar worker is a working class person who performs manual labor. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled jobs in:

Blue-collar work often involves something being physically built or maintained.

Blue-collar work is often paid hourly wage-labor, although some professionals may be paid by the project or salaried. There is a wide range of payscales for such work depending upon field of specialty and experience.

The term blue collar was first used in reference to trades jobs in 1924, in an Alden, Iowa newspaper. The phrase stems from the image of manual workers wearing blue denim or chambray shirts as part of their uniforms. Industrial and manual workers often wear durable canvas or cotton clothing that may be soiled during the course of their work.

Navy and light blue colors conceal potential dirt or grease on the worker's clothing, helping him or her to appear cleaner. For the same reason, blue is a popular color for boilersuits which protect workers' clothing. Some blue collar workers have uniforms with the name of the business and/or the individual's name embroidered or printed on it.

Historically the popularity of the color blue among manual laborers contrasts with the popularity of white dress shirts worn by people in office environments. The blue collar/white collar color scheme has socio-economic class connotations. However, this distinction has become blurred with the increasing importance of skilled labor, and the relative increase in low-paying white-collar jobs.

Educational Requirements:

Since many blue-collar jobs consist of mainly manual labor, educational requirements for workers are typically lower than those of white-collar workers. Often, only a high school diploma is required, and many of the skills required for blue-collar jobs will be learned by the employee while working.

In higher level jobs, vocational training or apprenticeships may be required, and for workers such as electricians and plumbers, state-certification is also necessary.

Blue collar shift to developing nations:

See also: Deindustrialization

With the information revolution, Western nations have moved towards a service and white collar economy. Many manufacturing jobs have been offshored to developing nations which pay their workers lower wages. This offshoring has pushed formerly agrarian nations to industrialized economies and concurrently decreased the number of blue-collar jobs in developed countries.

In the United States, blue collar and service occupations generally refer to jobs in precision production, craft, and repair occupations; machine operators and inspectors; transportation and moving occupations; handlers, equipment cleaners, helpers, and laborers.

In the United States an area known as the Rust Belt comprising the Northeast and Midwest, including Western New York and Western Pennsylvania, has seen its once large manufacturing base shrink significantly.

With the de-industrialization of these areas starting in the mid-1960s cities like Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Buffalo, New York; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Erie, Pennsylvania; Youngstown, Ohio; Toledo, Ohio, Rochester, New York, and St. Louis, Missouri, have experienced a steady decline of the blue-collar workforce and subsequent population decreases. Due to this economic osmosis, the rust belt has experienced high unemployment, poverty, and urban blight.

Automation and the Future:

Due to many blue-collar jobs involving manual labor and relatively unskilled workers, automation poses a threat of unemployment for blue-collar workers. One study from the MIT Technology Review estimates that 83% of jobs that make less than $20 per hour are threatened by automation.

Some examples of technology that threaten workers are self-driving cars and automated cleaning devices, which could place blue-collar workers such as truck drivers or janitors out of work.

Others have suggested that technological advancement will not lead to blue-collar job unemployment, but rather shifts in the types of work that blue-collar workers currently do.

Some foresee computer coding as becoming the blue-collar job of the future. Proponents of this idea view coding as a skill that can be learned through vocational training, and suggest that more coders will be needed in a technologically advancing world.

Others see future of blue-collar work as humans and computers working together to improve efficiency. Such jobs would consist of data-tagging and labeling.

Electoral Politics:

Blue-collar workers have played a large role in electoral politics. In the 2016 United States Presidential election, many attributed Donald Trump’s victories in the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan to blue-collar workers, who overwhelmingly favored Trump over opponent Hillary Clinton.

Amongst white-working class citizens, Trump won 64% of the votes, compared to only 32% for Clinton. This was the largest margin of victory amongst this group of voters for any presidential candidate since 1980.

Many attributed Trump’s success amongst this bloc of voters to his opposition of international trade deals and environmental regulations, two of the largest threats to blue-collar employment.

Opponents of this view believe Trump’s success with this bloc had more to do with an anti-immigrant and nationalist platform that supports deportation and discourages investment in higher education.

See also: ___________________________________________________________________________

Pink Collar Workers:

In the United States and (at least some) other English-speaking countries, a pink-collar worker refers to someone working in the care-oriented career field or in jobs historically considered to be "women’s work." This may include jobs in nursing, teaching, secretarial work, waitressing, or child care. While these jobs may be filled by men, they are typically female-dominated and may pay significantly less than white-collar or blue-collar jobs.

The term "pink-collar" was popularized in the late 1970s by writer and social critic Louise Kapp Howe to denote women working as nurses, secretaries, and elementary school teachers.

The term's origins, however, go back to the early 1970s, to when the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was placed before the states for ratification. At that time, the term was used to denote secretarial staff as well as non-professional office staff, all of which were largely held by women.

These positions were not white-collar jobs, but neither were they blue-collar, manual labor. Hence, the creation of the term "pink-collar," which indicated it was not white-collar, was nonetheless an office job and one that was overwhelmingly filled by women.

Occupations:

Pink-collar occupations tend to be personal-service-oriented worker working in retail, nursing, and teaching (depending on the level), are part of the service sector, and are among the most common occupations in the United States.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that, as of May 2008, there were over 2.2 million persons employed as servers in the United States. Furthermore, the World Health Organization's 2011 World Health Statistics Report states that there are 19.3 million nurses in the world today.

In the United States, women comprise 92.1% of the registered nurses that are currently employed:

Pink-collar occupations include:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Pink Collar Workers: ___________________________________________________________________________

Groups of working individuals are typically classified based on the colors of their collars worn at work; these can commonly reflect one's occupation or sometimes gender:

White Collar Workers:

In many countries (such as Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and United States), a white-collar worker is a person who performs professional, managerial, or administrative work.

White-collar work may be performed in an office or other administrative setting. Other types of work are those of a blue-collar worker, whose job requires manual labor and a pink-collar worker, whose labor is related to customer interaction, entertainment, sales, or other service-oriented work. Many occupations blend blue, white and pink (service) industry categorizations.

The term refers to the white dress shirts of male office workers common through most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Western countries, as opposed to the blue overalls worn by many manual laborers.

The term "white collar" is credited to Upton Sinclair, an American writer, in relation to contemporary clerical, administrative, and management workers during the 1930s, though references to white-collar work appear as early as 1935.

Demographics:

Formerly a minority in the agrarian and early industrial societies, white-collar workers have become a majority in industrialized countries due to modernization and outsourcing of manufacturing jobs.

The blue-collar and white-collar descriptors as it pertains to work dress may no longer be an accurate descriptor as office attire has broadened beyond a white shirt and tie. Employees in office environments may wear a variety of colors, may dress business casual or wear casual clothes altogether.

In addition work tasks have blurred. "White-collar" employees may perform "blue-collar" tasks (or vice versa). An example would be a restaurant manager who may wear more formal clothing yet still assist with cooking food or taking customers' orders or a construction worker who also performs desk work.

Health Effects:

Less physical activity among white-collar workers has been thought to be a key factor in increased life-style related health conditions such as:

- fatigue,

- obesity,

- diabetes,

- hypertension,

- cancer,

- and heart disease.

Workplace interventions such as alternative activity workstations, sit-stand desks, promotion of stair use are among measures being implemented to counter the harms of sedentary workplace environments.

A Cochrane systematic review published in 2018 concluded that "At present there is low-quality evidence that the use of sit-stand desks reduce workplace sitting." Also, evidence was lacking on the long term health benefits of such interventions.

See also: ___________________________________________________________________________

Blue-Collar Worker:

In many countries, a blue-collar worker is a working class person who performs manual labor. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled jobs in:

- manufacturing,

- mining,

- sanitation,

- custodial work,

- textile manufacturing,

- commercial fishing,

- food processing,

- oil field work,

- waste disposal and recycling,

- construction,

- mechanic,

- maintenance,

- warehousing,

- technical installation,

- and many other types of physical work.

Blue-collar work often involves something being physically built or maintained.

Blue-collar work is often paid hourly wage-labor, although some professionals may be paid by the project or salaried. There is a wide range of payscales for such work depending upon field of specialty and experience.

The term blue collar was first used in reference to trades jobs in 1924, in an Alden, Iowa newspaper. The phrase stems from the image of manual workers wearing blue denim or chambray shirts as part of their uniforms. Industrial and manual workers often wear durable canvas or cotton clothing that may be soiled during the course of their work.

Navy and light blue colors conceal potential dirt or grease on the worker's clothing, helping him or her to appear cleaner. For the same reason, blue is a popular color for boilersuits which protect workers' clothing. Some blue collar workers have uniforms with the name of the business and/or the individual's name embroidered or printed on it.

Historically the popularity of the color blue among manual laborers contrasts with the popularity of white dress shirts worn by people in office environments. The blue collar/white collar color scheme has socio-economic class connotations. However, this distinction has become blurred with the increasing importance of skilled labor, and the relative increase in low-paying white-collar jobs.

Educational Requirements:

Since many blue-collar jobs consist of mainly manual labor, educational requirements for workers are typically lower than those of white-collar workers. Often, only a high school diploma is required, and many of the skills required for blue-collar jobs will be learned by the employee while working.

In higher level jobs, vocational training or apprenticeships may be required, and for workers such as electricians and plumbers, state-certification is also necessary.

Blue collar shift to developing nations:

See also: Deindustrialization

With the information revolution, Western nations have moved towards a service and white collar economy. Many manufacturing jobs have been offshored to developing nations which pay their workers lower wages. This offshoring has pushed formerly agrarian nations to industrialized economies and concurrently decreased the number of blue-collar jobs in developed countries.

In the United States, blue collar and service occupations generally refer to jobs in precision production, craft, and repair occupations; machine operators and inspectors; transportation and moving occupations; handlers, equipment cleaners, helpers, and laborers.

In the United States an area known as the Rust Belt comprising the Northeast and Midwest, including Western New York and Western Pennsylvania, has seen its once large manufacturing base shrink significantly.

With the de-industrialization of these areas starting in the mid-1960s cities like Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Buffalo, New York; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Erie, Pennsylvania; Youngstown, Ohio; Toledo, Ohio, Rochester, New York, and St. Louis, Missouri, have experienced a steady decline of the blue-collar workforce and subsequent population decreases. Due to this economic osmosis, the rust belt has experienced high unemployment, poverty, and urban blight.

Automation and the Future:

Due to many blue-collar jobs involving manual labor and relatively unskilled workers, automation poses a threat of unemployment for blue-collar workers. One study from the MIT Technology Review estimates that 83% of jobs that make less than $20 per hour are threatened by automation.

Some examples of technology that threaten workers are self-driving cars and automated cleaning devices, which could place blue-collar workers such as truck drivers or janitors out of work.

Others have suggested that technological advancement will not lead to blue-collar job unemployment, but rather shifts in the types of work that blue-collar workers currently do.

Some foresee computer coding as becoming the blue-collar job of the future. Proponents of this idea view coding as a skill that can be learned through vocational training, and suggest that more coders will be needed in a technologically advancing world.

Others see future of blue-collar work as humans and computers working together to improve efficiency. Such jobs would consist of data-tagging and labeling.

Electoral Politics:

Blue-collar workers have played a large role in electoral politics. In the 2016 United States Presidential election, many attributed Donald Trump’s victories in the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan to blue-collar workers, who overwhelmingly favored Trump over opponent Hillary Clinton.

Amongst white-working class citizens, Trump won 64% of the votes, compared to only 32% for Clinton. This was the largest margin of victory amongst this group of voters for any presidential candidate since 1980.

Many attributed Trump’s success amongst this bloc of voters to his opposition of international trade deals and environmental regulations, two of the largest threats to blue-collar employment.

Opponents of this view believe Trump’s success with this bloc had more to do with an anti-immigrant and nationalist platform that supports deportation and discourages investment in higher education.

See also: ___________________________________________________________________________

Pink Collar Workers:

In the United States and (at least some) other English-speaking countries, a pink-collar worker refers to someone working in the care-oriented career field or in jobs historically considered to be "women’s work." This may include jobs in nursing, teaching, secretarial work, waitressing, or child care. While these jobs may be filled by men, they are typically female-dominated and may pay significantly less than white-collar or blue-collar jobs.

The term "pink-collar" was popularized in the late 1970s by writer and social critic Louise Kapp Howe to denote women working as nurses, secretaries, and elementary school teachers.

The term's origins, however, go back to the early 1970s, to when the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was placed before the states for ratification. At that time, the term was used to denote secretarial staff as well as non-professional office staff, all of which were largely held by women.

These positions were not white-collar jobs, but neither were they blue-collar, manual labor. Hence, the creation of the term "pink-collar," which indicated it was not white-collar, was nonetheless an office job and one that was overwhelmingly filled by women.

Occupations:

Pink-collar occupations tend to be personal-service-oriented worker working in retail, nursing, and teaching (depending on the level), are part of the service sector, and are among the most common occupations in the United States.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that, as of May 2008, there were over 2.2 million persons employed as servers in the United States. Furthermore, the World Health Organization's 2011 World Health Statistics Report states that there are 19.3 million nurses in the world today.

In the United States, women comprise 92.1% of the registered nurses that are currently employed:

Pink-collar occupations include:

- Car attendant / Washroom attendant

- Meter Maid / Parking lot attendant

- Librarian / Teacher-librarian

- Library assistant / Library technician

- Preschool teacher / Early childhood educator / Kindergarten teacher

- Special education teacher

- Teaching assistant

- Nurse / Registered nurse / Wet nurse

- Dental assistant / Medical assistant / Pharmacy assistant

- Dental hygienist

- Rehabilitation specialist

- Nutritionist / Dietitian

- Hospital attendant / Hospital service worker / Nurse's aide

- Advertising and promotions managers

- Bank teller

- Bookkeeper

- Marketing coordinator / Marketing assistant

- Human resources manager

- Legal secretary

- Paralegal

- Public relations manager

- Receptionist / Secretary / Administrative Assistant / Information clerk

- Hairstylist / Barber / Hair colorist

- Dressmaker / Costume designer / Tailor / Image consultant

- Cosmetologist / Make-up artist / Nail technician / Perfumer / Esthetician

- Model

- Personal stylist / Fashion stylist

- Buyer

- Valet

- Waitress / Barista / Bartender

- Flight attendant / stewardess

- Museum docents / Tour guide

- Casino host

- Babysitter / Day care worker / Nanny / Child-care provider / Caregiver

- Maid / Domestic worker / Governess

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Pink Collar Workers: ___________________________________________________________________________

Gold Collar Workers:

Gold-collar worker (GCW) is a neologism which has been used to describe either young, low-wage workers who invest in conspicuous luxury, or highly skilled knowledge workers, traditionally classified as white collar, but who have recently become essential enough to business operations as to warrant a new classification.

The main challenge faced by gold-collar workers is the short-lived nature of their financial security. More often than not, these people marry and have children, and take on additional financial responsibilities such as mortgages and health insurance.

With partial or no higher education, however, their job prospects could be viewed as narrow and fairly restricted.

Gold Collar often refers to entry level workers (or unskilled workers from middle-class families), in their twenties who want flex time hours, self-control, independence, empowerment, to furnish their own offices, a signing bonus, full tuition reimbursement, flex benefits, to work as a team, casual Friday every day, to work from home, to have fun, and don't want to feel loyal to the company.

Overview:

It has been reported that the term 'gold-collar worker' was first used by Robert Earl Kelley in his 1985 book The Gold-Collar Worker: Harnessing the Brainpower of the New Work Force.

Here he discussed a new generation of workers who use American business' most important resource, brainpower.

A quote from the book summary states, "They are a new breed of workers, and they demand a new kind of management. Intelligent, independent, and innovative, these employees are incredibly valuable. They are scientists and mathematicians, doctors and lawyers, engineers and computer programmers, stock analysts and even community planners. They are as distinct from their less skilled white-collar counterparts—bank tellers, bookkeepers, clerks, and other business functionaries—as they are from blue-collar laborers. And they account for over 40 percent of America's workforce."

The color gold applies to these workers because they are highly skilled. When Kelley's book was published in 1985, these were typically understood as being young, college-educated, and specialized.

See also:

Gold-collar worker (GCW) is a neologism which has been used to describe either young, low-wage workers who invest in conspicuous luxury, or highly skilled knowledge workers, traditionally classified as white collar, but who have recently become essential enough to business operations as to warrant a new classification.