Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Nutrition

covers the foods and liquids we consume, including their nutritional value, as well as the dining experience: whether at restaurants or at home, including grocery shopping. For many, the opportunity to work as a Chef through cooking schools as well as food TV networks. Also covers obesity, malnutrition and hunger, along with regulation of drugs and foods by the government.

Also: go to any of the following Related Web Pages:

American Lifestyles

Health & Fitness

The following covers all forms of Human Nutrition including Cuisine as well as social issues for Obesity and Hunger in the United States

YouTube Video from the White House: Introducing the New Food Icon: MyPlate

(The Department of Agriculture introduces the new food icon, MyPlate, to replace the MyPyramid image as the government's primary food group symbol. An easy-to-understand visual cue to help consumers adopt healthy eating habits, MyPlate is consistent with the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.)

Human nutrition

Refers to the provision of essential nutrients necessary to support human life and health.

Generally, people can survive up to 40 days without food, a period largely depending on the amount of water consumed, stored body fat, muscle mass and genetic factors.

Poor nutrition is a chronic problem often linked to poverty, poor nutrition understanding and practices, and deficient sanitation and food security. Lack of proper nutrition contributes to lower academic performance, lower test scores, and eventually less successful students and a less productive and competitive economy.

Malnutrition and its consequences are immense contributors to deaths and disabilities worldwide. Promoting good nutrition helps children grow, promotes human development and advances economic growth and eradication of poverty.

Click on any of the following for amplification about Human Nutrition:

Cuisine:

Cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region.

A cuisine is primarily influenced by the ingredients that are available locally or through trade. Religious food laws, such as Hindu, Islamic and Jewish dietary laws, can also exercise a strong influence on cuisine. Regional food preparation traditions, customs and ingredients often combine to create dishes unique to a particular region.

Click on any of the following for amplification about Cuisine:

___________________________________________________________________________

Obesity in the United States:

Obesity in the United States has been increasingly cited as a major health issue in recent decades.

While many industrialized countries have experienced similar increases, obesity rates in the United States are among the highest in the world.

Obesity has continued to grow within the United States. Two out of every three Americans are considered to be overweight or obese. During the early 21st century, America often contained the highest percentage of obese people in the world. Obesity has led to over 120,000 preventable deaths each year in the United States.

An obese person in America incurs an average of $1,429 more in medical expenses annually. Approximately $147 billion is spent in added medical expenses per year within the United States.

The United States had the highest rate of obesity within the OECD grouping of large trading economies, until obesity rates in Mexico surpassed those of the United States in 2013. From 13% obesity in 1962, estimates have steadily increased.

The following statistics comprise adults age 20 and over living at or near the poverty level.

The obesity percentages for the overall US population are higher reaching:

The organization estimates that 3/4 of the American population will likely be overweight or obese by 2020. The latest figures from the CDC show that more than one-third (34.9% or 78.6 million) of U.S. adults are obese and 17% for children and adolescents aged 2–19 years.

Obesity has been cited as a contributing factor to approximately 100,000–400,000 deaths in the United States per year and has increased health care use and expenditures, costing society an estimated $117 billion in direct (preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services related to weight) and indirect (absenteeism, loss of future earnings due to premature death) costs.

This exceeds health-care costs associated with smoking and accounts for 6% to 12% of national health care expenditures in the United States.

Click on any of the following about obesity in the United States:

___________________________________________________________________________

Hunger in the United States:

Hunger in the United States is an issue that affects millions of Americans, including some who are middle class, or who are in households where all adults are in work.

Research from the Food Safety and Inspection Service found that 14.9% of American households were food insecure during 2011, with 5.7% suffering from very low food security. Journalists and charity workers have reported further increased demand for emergency food aid during 2012 and 2013.

The United States produces far more food than it needs for domestic consumption - hunger within the U.S. is caused by some Americans having insufficient money to buy food for themselves or their families.

Hunger is addressed by a mix of public and private food aid provision. Both types of aid have been expanding in the 21st century, with hunger relief efforts by the government growing faster than aid provided by civil society.

Historically, the U.S. has been a world leader in reducing hunger. While precise comparative figures are not available, studies suggest that in the 18th century there was far less hunger in the United States than in the rest of the world. In the 19th and early 20th century western Europe began to catch up. After the outbreak of World War I however, the U.S. was able to send tens of millions of tons of food to relieve severe hunger in Europe. This act was unprecedented in the world's history, and was the first of many substantial actions by the United States to relieve international hunger and poverty.

In the later half of the twentieth century, other advanced economies in Europe and Asia began to overtake the U.S. in terms of reducing hunger among their own populations. In 2011, a report presented in the New York Times found that among 20 economies recognized as advanced by the International Monetary Fund and for which comparative rankings for food security were available, the U.S. was joint worst.

Nonetheless, in March 2013, the Global Food Security Index commissioned by DuPont, ranked the U.S. number one for food affordability and overall food security.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Hunger in the United States:

Refers to the provision of essential nutrients necessary to support human life and health.

Generally, people can survive up to 40 days without food, a period largely depending on the amount of water consumed, stored body fat, muscle mass and genetic factors.

Poor nutrition is a chronic problem often linked to poverty, poor nutrition understanding and practices, and deficient sanitation and food security. Lack of proper nutrition contributes to lower academic performance, lower test scores, and eventually less successful students and a less productive and competitive economy.

Malnutrition and its consequences are immense contributors to deaths and disabilities worldwide. Promoting good nutrition helps children grow, promotes human development and advances economic growth and eradication of poverty.

Click on any of the following for amplification about Human Nutrition:

- Overview

- Nutrients

- Malnutrition

- Global nutrition challenges

- International food insecurity and malnutrition

- Nutrition access disparities

- Nutrition policy

- Nutrition for special populations

- History

- See also

Cuisine:

Cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region.

A cuisine is primarily influenced by the ingredients that are available locally or through trade. Religious food laws, such as Hindu, Islamic and Jewish dietary laws, can also exercise a strong influence on cuisine. Regional food preparation traditions, customs and ingredients often combine to create dishes unique to a particular region.

Click on any of the following for amplification about Cuisine:

___________________________________________________________________________

Obesity in the United States:

Obesity in the United States has been increasingly cited as a major health issue in recent decades.

While many industrialized countries have experienced similar increases, obesity rates in the United States are among the highest in the world.

Obesity has continued to grow within the United States. Two out of every three Americans are considered to be overweight or obese. During the early 21st century, America often contained the highest percentage of obese people in the world. Obesity has led to over 120,000 preventable deaths each year in the United States.

An obese person in America incurs an average of $1,429 more in medical expenses annually. Approximately $147 billion is spent in added medical expenses per year within the United States.

The United States had the highest rate of obesity within the OECD grouping of large trading economies, until obesity rates in Mexico surpassed those of the United States in 2013. From 13% obesity in 1962, estimates have steadily increased.

The following statistics comprise adults age 20 and over living at or near the poverty level.

The obesity percentages for the overall US population are higher reaching:

- 19.4% in 1997,

- 24.5% in 2004,

- 26.6% in 2007,

- and 33.8% (adults) and 17% (children) in 2008.

- In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported higher numbers once more, counting 35.7% of American adults as obese, and 17% of American children.

- In 2013 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that 27.6% of American citizens were obese.

The organization estimates that 3/4 of the American population will likely be overweight or obese by 2020. The latest figures from the CDC show that more than one-third (34.9% or 78.6 million) of U.S. adults are obese and 17% for children and adolescents aged 2–19 years.

Obesity has been cited as a contributing factor to approximately 100,000–400,000 deaths in the United States per year and has increased health care use and expenditures, costing society an estimated $117 billion in direct (preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services related to weight) and indirect (absenteeism, loss of future earnings due to premature death) costs.

This exceeds health-care costs associated with smoking and accounts for 6% to 12% of national health care expenditures in the United States.

Click on any of the following about obesity in the United States:

- Prevalence

- Epidemiology

- Contributing factors to obesity epidemic

- Total costs to the US

- Effects on life expectancy

- Anti-obesity efforts

- Accommodations

- See also:

- List of countries by Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Obesogen

- EPODE International Network, the world's largest obesity-prevention network

- World Fit, a program of the United States Olympic Committee

- Fat acceptance movement

- Documentaries:

___________________________________________________________________________

Hunger in the United States:

Hunger in the United States is an issue that affects millions of Americans, including some who are middle class, or who are in households where all adults are in work.

Research from the Food Safety and Inspection Service found that 14.9% of American households were food insecure during 2011, with 5.7% suffering from very low food security. Journalists and charity workers have reported further increased demand for emergency food aid during 2012 and 2013.

The United States produces far more food than it needs for domestic consumption - hunger within the U.S. is caused by some Americans having insufficient money to buy food for themselves or their families.

Hunger is addressed by a mix of public and private food aid provision. Both types of aid have been expanding in the 21st century, with hunger relief efforts by the government growing faster than aid provided by civil society.

Historically, the U.S. has been a world leader in reducing hunger. While precise comparative figures are not available, studies suggest that in the 18th century there was far less hunger in the United States than in the rest of the world. In the 19th and early 20th century western Europe began to catch up. After the outbreak of World War I however, the U.S. was able to send tens of millions of tons of food to relieve severe hunger in Europe. This act was unprecedented in the world's history, and was the first of many substantial actions by the United States to relieve international hunger and poverty.

In the later half of the twentieth century, other advanced economies in Europe and Asia began to overtake the U.S. in terms of reducing hunger among their own populations. In 2011, a report presented in the New York Times found that among 20 economies recognized as advanced by the International Monetary Fund and for which comparative rankings for food security were available, the U.S. was joint worst.

Nonetheless, in March 2013, the Global Food Security Index commissioned by DuPont, ranked the U.S. number one for food affordability and overall food security.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Hunger in the United States:

- Causes

- Impact of hunger

- Fighting hunger

- History

- See also:

- A Place at the Table

- Basic income

- Basic income in the United States

- Economic issues in the United States

- Feeding America

- Food Bank

- Food Donation Connection

- Fome Zero (Hunger 0)

- Global Hunger Index

- Homelessness in the United States

- Human rights

- Hunger

- The Hunger Project

- Income inequality in the United States

- Malnutrition in the United States

- Poverty in the United States

- Right to food* Category:Hunger relief organizations

- Social programs in the United States

- Soup kitchen

- United States Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs

The Many Forms of Cuisine Found in the United States

YouTube Video: how to use Chop Sticks to eat Chinese Food

Pictured: a Presentation of Italian Cuisine

The cuisine of the United States reflects its history. The European colonization of the Americas yielded the introduction of a number of ingredients and cooking styles to the latter. The various styles continued expanding well into the 19th and 20th centuries, proportional to the influx of immigrants from many foreign nations; such influx developed a rich diversity in food preparation throughout the country.

Early Native Americans utilized a number of cooking methods in early American Cuisine that have been blended with early European cooking methods to form the basis of American Cuisine.

When the colonists came to the colonies, they farmed animals for clothing and meat in a similar fashion to what they had done in Europe. They had cuisine similar to their previous British cuisine.

The American colonial diet varied depending on the settled region in which someone lived. Commonly hunted game included deer, bear, buffalo, and wild turkey. A number of fats and oils made from animals served to cook much of the colonial foods. Prior to the Revolution,

New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer, as maritime trade provided them relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items: rum was the distilled spirit of choice, as the main ingredient, molasses, was readily available from trade with the West Indies.

In comparison to the northern colonies, the southern colonies were quite diverse in their agricultural diet and did not have a central region of culture.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans developed many new foods. During the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) food production and presentation became more industrialized. One characteristic of American cooking is the fusion of multiple ethnic or regional approaches into completely new cooking styles.

A wave of celebrity chefs began with Julia Child and Graham Kerr in the 1970s, with many more following after the rise of cable channels such as Food Network.

Click on any of the blue hyperlinks below for further amplification:

Early Native Americans utilized a number of cooking methods in early American Cuisine that have been blended with early European cooking methods to form the basis of American Cuisine.

When the colonists came to the colonies, they farmed animals for clothing and meat in a similar fashion to what they had done in Europe. They had cuisine similar to their previous British cuisine.

The American colonial diet varied depending on the settled region in which someone lived. Commonly hunted game included deer, bear, buffalo, and wild turkey. A number of fats and oils made from animals served to cook much of the colonial foods. Prior to the Revolution,

New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer, as maritime trade provided them relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items: rum was the distilled spirit of choice, as the main ingredient, molasses, was readily available from trade with the West Indies.

In comparison to the northern colonies, the southern colonies were quite diverse in their agricultural diet and did not have a central region of culture.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans developed many new foods. During the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) food production and presentation became more industrialized. One characteristic of American cooking is the fusion of multiple ethnic or regional approaches into completely new cooking styles.

A wave of celebrity chefs began with Julia Child and Graham Kerr in the 1970s, with many more following after the rise of cable channels such as Food Network.

Click on any of the blue hyperlinks below for further amplification:

Different Restaurant Themes, including Fast Food

YouTube Video The Spago flagship restaurant in Beverly Hills*

*- co-founders Wolfgang Puck and Barbara Lazaroff

Click on the following blue hyperlinks to find the closest restaurant for: Red Lobster or O'Charleys

Pictured: The first McDonalds Fast Food Chain and now a museum in Des Plaines, Illinois, U.S.

And the Hollywood "Hard Rock Cafe"

Various types of restaurant fall into several industry classifications based upon menu style, preparation methods and pricing. Additionally, how the food is served to the customer helps to determine the classification.

Historically, restaurant referred only to places that provided tables where one sat down to eat the meal, typically served by a waiter. Following the rise of fast food and take-out restaurants, a retronym for the older "standard" restaurant was created, sit-down restaurant.

Most commonly, "sit-down restaurant" refers to a casual dining restaurant with table service, rather than a fast food restaurant or a diner, where one orders food at a counter. Sit-down restaurants are often further categorized, in North America, as "family-style" or "formal".

In Dishing It Out: In Search of the Restaurant Experience, Robert Appelbaum argues that all restaurants can be categorized according to a set of social parameters defined as polar opposites: high or low, cheap or dear, familiar or exotic, formal or informal, and so forth. Any restaurant will be relatively high or low in style and price, familiar or exotic in the cuisine it offers to different kinds of customers, and so on.

Context is as important as the style and form: a taqueria is a more than familiar site in Guadalajara, Mexico, but it would be exotic in Albania. A Ruth's Chris restaurant in America may seem somewhat strange to a first time visitor from India; but many Americans are familiar with it as a large restaurant chain, albeit one that features high prices and a formal atmosphere.

Click on the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

Historically, restaurant referred only to places that provided tables where one sat down to eat the meal, typically served by a waiter. Following the rise of fast food and take-out restaurants, a retronym for the older "standard" restaurant was created, sit-down restaurant.

Most commonly, "sit-down restaurant" refers to a casual dining restaurant with table service, rather than a fast food restaurant or a diner, where one orders food at a counter. Sit-down restaurants are often further categorized, in North America, as "family-style" or "formal".

In Dishing It Out: In Search of the Restaurant Experience, Robert Appelbaum argues that all restaurants can be categorized according to a set of social parameters defined as polar opposites: high or low, cheap or dear, familiar or exotic, formal or informal, and so forth. Any restaurant will be relatively high or low in style and price, familiar or exotic in the cuisine it offers to different kinds of customers, and so on.

Context is as important as the style and form: a taqueria is a more than familiar site in Guadalajara, Mexico, but it would be exotic in Albania. A Ruth's Chris restaurant in America may seem somewhat strange to a first time visitor from India; but many Americans are familiar with it as a large restaurant chain, albeit one that features high prices and a formal atmosphere.

Click on the following blue hyperlinks for further amplification:

- Types

- Variations

- See also:

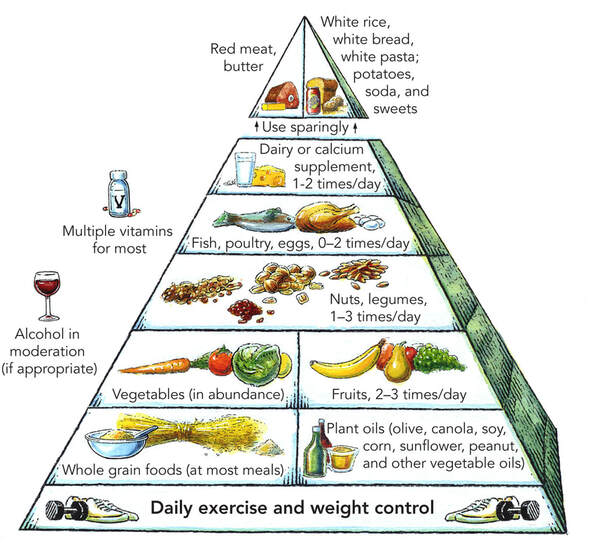

History of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrition Guides including a List of USDA Nutrition Guides along with the Nutrition Facts Label

YouTube Video: Mayo Clinic Minute: How to read the new Nutrition Facts label

Pictured below: (TOP) The MyPlate nutrition guide; (BOTTOM): Nutritional Facts Label

The history of USDA nutrition guides includes over 100 years of American nutrition advice. The guides have been updated over time, to adopt new scientific findings and new public health marketing techniques.

The current guidelines are the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020. Over time they have described from 4 to 11 food groups. Various guides have been criticized as not accurately representing scientific information about optimal nutrition, and as being overly influenced by the agricultural industries the USDA promotes.

MyPlate:

Main article: MyPlate

MyPlate is the current nutrition guide published by the United States Department of Agriculture, consisting of a diagram of a plate and glass divided into five food groups. It replaced the USDA's MyPyramid diagram on June 2, 2011, ending 19 years of food pyramid iconography. The guide will be displayed on food packaging and used in nutritional education in the United States.

Dietary Guidelines:

Main article: Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in the USDA and the United States Department of Health and Human Services jointly released a longer textual document called Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020, to be updated in 2020.

The first edition was published in 1980, and since 1985 has been updated every five years by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Like the USDA Food Pyramid, these guidelines have been criticized as being overly influenced by the agriculture industry. These criticisms of the Dietary Guidelines arose due to the omission of high-quality evidence that the Public Health Service decided to exclude.

The phrasing of recommendations was extremely important and widely affected everyone who read it. The wording had to be changed constantly as there were protests due to comments such as “cut down on fatty meats”, which led to the U.S Department of Agriculture having to stop the publication of the USDA Food Book.

Slight alterations of various dietary guidelines had to be made throughout the 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to calm down the protests emerged. As a compromise, the phrase was changed to “choose lean meat” but didn’t result in a better situation. In 2015 the committee factored in environmental sustainability for the first time in its recommendations.

The committee's 2015 report found that a healthy diet should comprise higher plant based foods and lower animal based foods. It also found that a plant food based diet was better for the environment than one based on meat and dairy.

In 2013 and again in 2015, Edward Archer and colleagues published a series of research articles in PlosOne and Mayo Clinic Proceedings demonstrating that the dietary data used to develop the US Dietary Guidelines were physiologically implausible (i.e., incompatible with survival) and therefore these data were "inadmissible" as scientific evidence and should not be used to inform public policy.

In 2016, Nina Teicholz authored a critique of the US Dietary Guidelines in the British Medical Journal titled The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? Teicholz suggested that "the scientific committee advising the US government has not used standard methods for most of its analyses and instead relies heavily on systematic reviews from professional bodies such as the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, which are heavily supported by food and drug companies."

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the History of the USDA Nutrition Guides:

Nutrition Facts Label

The nutrition facts label (also known as the nutrition information panel, and other slight variations) is a label required on most packaged food in many countries. Most countries also release overall nutrition guides for general educational purposes. In some cases, the guides are based on different dietary targets for various nutrients than the labels on specific foods.

Nutrition facts labels are only one of many types of food label required by regulation or applied by manufacturers.

In the United States, the Nutritional Facts label lists the percentage supplied that is recommended to be met, or to be limited, in one day of human nutrients based on a daily diet of 2,000 calories.

With certain exceptions, such as foods meant for babies, the following Daily Values are used. These are called Reference Daily Intake (RDI) values and were originally based on the highest 1968 Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) for each nutrient in order to assure that the needs of all age and sex combinations were met.

These are older than the current Recommended Dietary Allowances of the Dietary Reference Intake. For vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and manganese, the current highest RDAs are up to 50% higher than the older Daily Values used in labeling, whereas for other nutrients the recommended needs have gone down.

A side-by-side table of the old and new adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake. As of October 2010, the only micronutrients that are required to be included on all labels are vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron. To determine the nutrient levels in the foods, companies may develop or use databases, and these may be submitted voluntarily to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for review.

For more about the Nutrition Facts Label, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

The current guidelines are the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020. Over time they have described from 4 to 11 food groups. Various guides have been criticized as not accurately representing scientific information about optimal nutrition, and as being overly influenced by the agricultural industries the USDA promotes.

MyPlate:

Main article: MyPlate

MyPlate is the current nutrition guide published by the United States Department of Agriculture, consisting of a diagram of a plate and glass divided into five food groups. It replaced the USDA's MyPyramid diagram on June 2, 2011, ending 19 years of food pyramid iconography. The guide will be displayed on food packaging and used in nutritional education in the United States.

Dietary Guidelines:

Main article: Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in the USDA and the United States Department of Health and Human Services jointly released a longer textual document called Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020, to be updated in 2020.

The first edition was published in 1980, and since 1985 has been updated every five years by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Like the USDA Food Pyramid, these guidelines have been criticized as being overly influenced by the agriculture industry. These criticisms of the Dietary Guidelines arose due to the omission of high-quality evidence that the Public Health Service decided to exclude.

The phrasing of recommendations was extremely important and widely affected everyone who read it. The wording had to be changed constantly as there were protests due to comments such as “cut down on fatty meats”, which led to the U.S Department of Agriculture having to stop the publication of the USDA Food Book.

Slight alterations of various dietary guidelines had to be made throughout the 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to calm down the protests emerged. As a compromise, the phrase was changed to “choose lean meat” but didn’t result in a better situation. In 2015 the committee factored in environmental sustainability for the first time in its recommendations.

The committee's 2015 report found that a healthy diet should comprise higher plant based foods and lower animal based foods. It also found that a plant food based diet was better for the environment than one based on meat and dairy.

In 2013 and again in 2015, Edward Archer and colleagues published a series of research articles in PlosOne and Mayo Clinic Proceedings demonstrating that the dietary data used to develop the US Dietary Guidelines were physiologically implausible (i.e., incompatible with survival) and therefore these data were "inadmissible" as scientific evidence and should not be used to inform public policy.

In 2016, Nina Teicholz authored a critique of the US Dietary Guidelines in the British Medical Journal titled The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? Teicholz suggested that "the scientific committee advising the US government has not used standard methods for most of its analyses and instead relies heavily on systematic reviews from professional bodies such as the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, which are heavily supported by food and drug companies."

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the History of the USDA Nutrition Guides:

- Earliest guides

- Basic 7

- Basic Four

- Food Guide Pyramid and its Controversy

- MyPyramid

- See also:

Nutrition Facts Label

The nutrition facts label (also known as the nutrition information panel, and other slight variations) is a label required on most packaged food in many countries. Most countries also release overall nutrition guides for general educational purposes. In some cases, the guides are based on different dietary targets for various nutrients than the labels on specific foods.

Nutrition facts labels are only one of many types of food label required by regulation or applied by manufacturers.

In the United States, the Nutritional Facts label lists the percentage supplied that is recommended to be met, or to be limited, in one day of human nutrients based on a daily diet of 2,000 calories.

With certain exceptions, such as foods meant for babies, the following Daily Values are used. These are called Reference Daily Intake (RDI) values and were originally based on the highest 1968 Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) for each nutrient in order to assure that the needs of all age and sex combinations were met.

These are older than the current Recommended Dietary Allowances of the Dietary Reference Intake. For vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and manganese, the current highest RDAs are up to 50% higher than the older Daily Values used in labeling, whereas for other nutrients the recommended needs have gone down.

A side-by-side table of the old and new adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake. As of October 2010, the only micronutrients that are required to be included on all labels are vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron. To determine the nutrient levels in the foods, companies may develop or use databases, and these may be submitted voluntarily to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for review.

For more about the Nutrition Facts Label, click on any of the following blue hyperlinks:

Foods that We Consume including a List of Foods Humans Eat

YouTube Video about Food Safety (by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Pictured below: Eating with a Conscience — Beyond Pesticides

Click here for a List of Foods Humans Eat.

Food is any substance consumed to provide nutritional support for an organism. It is usually of plant or animal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth.

Historically, humans secured food through two methods: hunting and gathering and agriculture.

Today, the majority of the food energy required by the ever increasing population of the world is supplied by the food industry.

Food safety and food security are monitored by agencies like the International Association for Food Protection, World Resources Institute, World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization, and International Food Information Council. They address issues such as sustainability, biological diversity, climate change, nutritional economics, population growth, water supply, and access to food.

The right to food is a human right derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), recognizing the "right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food", as well as the "fundamental right to be free from hunger".

Food Sources:

Most food has its origin in plants. Some food is obtained directly from plants; but even animals that are used as food sources are raised by feeding them food derived from plants. Cereal grain is a staple food that provides more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop. Corn (maize), wheat, and rice – in all of their varieties – account for 87% of all grain production worldwide. Most of the grain that is produced worldwide is fed to livestock.

Some foods not from animal or plant sources include various edible fungi, especially mushrooms. Fungi and ambient bacteria are used in the preparation of fermented and pickled foods like leavened bread, alcoholic drinks, cheese, pickles, kombucha, and yogurt. Another example is blue-green algae such as Spirulina. Inorganic substances such as salt, baking soda and cream of tartar are used to preserve or chemically alter an ingredient.

Plants:

See also: Herb and spice

Many plants and plant parts are eaten as food and around 2,000 plant species are cultivated for food. Many of these plant species have several distinct cultivars.

Seeds of plants are a good source of food for animals, including humans, because they contain the nutrients necessary for the plant's initial growth, including many healthful fats, such as omega fats. In fact, the majority of food consumed by human beings are seed-based foods.

Edible seeds include:

Oilseeds are often pressed to produce rich oils:

Seeds are typically high in unsaturated fats and, in moderation, are considered a health food.

However, not all seeds are edible. Large seeds, such as those from a lemon, pose a choking hazard, while seeds from cherries and apples contain cyanide which could be poisonous only if consumed in large volumes.

Fruits are the ripened ovaries of plants, including the seeds within. Many plants and animals have coevolved such that the fruits of the former are an attractive food source to the latter, because animals that eat the fruits may excrete the seeds some distance away. Fruits, therefore, make up a significant part of the diets of most cultures. Some botanical fruits, such as tomatoes, pumpkins, and eggplants, are eaten as vegetables. (For more information, see list of fruits.)

Vegetables are a second type of plant matter that is commonly eaten as food. These include root vegetables (potatoes and carrots), bulbs (onion family), leaf vegetables (spinach and lettuce), stem vegetables (bamboo shoots and asparagus), and inflorescence vegetables (globe artichokes and broccoli and other vegetables such as cabbage or cauliflower).

Animals:

Main articles: Animal source foods and Food chain

Animals are used as food either directly or indirectly by the products they produce. Meat is an example of a direct product taken from an animal, which comes from muscle systems or from organs.

Food products produced by animals include milk produced by mammary glands, which in many cultures is drunk or processed into dairy products (cheese, butter, etc.).

In addition, birds and other animals lay eggs, which are often eaten, and bees produce honey, a reduced nectar from flowers, which is a popular sweetener in many cultures.

Some cultures consume blood, sometimes in the form of blood sausage, as a thickener for sauces, or in a cured, salted form for times of food scarcity, and others use blood in stews such as jugged hare.

Some cultures and people do not consume meat or animal food products for cultural, dietary, health, ethical, or ideological reasons. Vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Vegans do not consume any foods that are or contain ingredients from an animal source.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Foods consumed by Humans:

Food is any substance consumed to provide nutritional support for an organism. It is usually of plant or animal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth.

Historically, humans secured food through two methods: hunting and gathering and agriculture.

Today, the majority of the food energy required by the ever increasing population of the world is supplied by the food industry.

Food safety and food security are monitored by agencies like the International Association for Food Protection, World Resources Institute, World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization, and International Food Information Council. They address issues such as sustainability, biological diversity, climate change, nutritional economics, population growth, water supply, and access to food.

The right to food is a human right derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), recognizing the "right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food", as well as the "fundamental right to be free from hunger".

Food Sources:

Most food has its origin in plants. Some food is obtained directly from plants; but even animals that are used as food sources are raised by feeding them food derived from plants. Cereal grain is a staple food that provides more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop. Corn (maize), wheat, and rice – in all of their varieties – account for 87% of all grain production worldwide. Most of the grain that is produced worldwide is fed to livestock.

Some foods not from animal or plant sources include various edible fungi, especially mushrooms. Fungi and ambient bacteria are used in the preparation of fermented and pickled foods like leavened bread, alcoholic drinks, cheese, pickles, kombucha, and yogurt. Another example is blue-green algae such as Spirulina. Inorganic substances such as salt, baking soda and cream of tartar are used to preserve or chemically alter an ingredient.

Plants:

See also: Herb and spice

Many plants and plant parts are eaten as food and around 2,000 plant species are cultivated for food. Many of these plant species have several distinct cultivars.

Seeds of plants are a good source of food for animals, including humans, because they contain the nutrients necessary for the plant's initial growth, including many healthful fats, such as omega fats. In fact, the majority of food consumed by human beings are seed-based foods.

Edible seeds include:

Oilseeds are often pressed to produce rich oils:

- sunflower,

- flaxseed,

- rapeseed (including canola oil),

- sesame,

- et cetera.

Seeds are typically high in unsaturated fats and, in moderation, are considered a health food.

However, not all seeds are edible. Large seeds, such as those from a lemon, pose a choking hazard, while seeds from cherries and apples contain cyanide which could be poisonous only if consumed in large volumes.

Fruits are the ripened ovaries of plants, including the seeds within. Many plants and animals have coevolved such that the fruits of the former are an attractive food source to the latter, because animals that eat the fruits may excrete the seeds some distance away. Fruits, therefore, make up a significant part of the diets of most cultures. Some botanical fruits, such as tomatoes, pumpkins, and eggplants, are eaten as vegetables. (For more information, see list of fruits.)

Vegetables are a second type of plant matter that is commonly eaten as food. These include root vegetables (potatoes and carrots), bulbs (onion family), leaf vegetables (spinach and lettuce), stem vegetables (bamboo shoots and asparagus), and inflorescence vegetables (globe artichokes and broccoli and other vegetables such as cabbage or cauliflower).

Animals:

Main articles: Animal source foods and Food chain

Animals are used as food either directly or indirectly by the products they produce. Meat is an example of a direct product taken from an animal, which comes from muscle systems or from organs.

Food products produced by animals include milk produced by mammary glands, which in many cultures is drunk or processed into dairy products (cheese, butter, etc.).

In addition, birds and other animals lay eggs, which are often eaten, and bees produce honey, a reduced nectar from flowers, which is a popular sweetener in many cultures.

Some cultures consume blood, sometimes in the form of blood sausage, as a thickener for sauces, or in a cured, salted form for times of food scarcity, and others use blood in stews such as jugged hare.

Some cultures and people do not consume meat or animal food products for cultural, dietary, health, ethical, or ideological reasons. Vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Vegans do not consume any foods that are or contain ingredients from an animal source.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Foods consumed by Humans:

- Production

- Taste perception

- Cuisine

- Commercial trade

- Famine and hunger including Food aid

- Safety

- Diet

- Nutrition and dietary problems

- Legal definition

- Types of food

- See also:

- Agronomy portal

- Bulk foods

- Beverages

- Food and Bioprocess Technology

- Food engineering

- Food Inc., a 2009 documentary

- Food security

- Future food technology

- Lists of prepared foods

- Non-food crop

- Optimal foraging theory

- Outline of cooking

- Outline of nutrition

- Packaging and labeling

- Traditional food

- Urban farming

- Food Justice

Food Science

YouTube Video: Food Science – Learn the Science Behind the Food You Eat

(by Barnes-Jewish Hospital)

Pictured Below: Advances in Nutrition & Food Science is an international, peer-reviewed journal

Food science is the applied science devoted to the study of food. The Institute of Food Technologists defines food science as "the discipline in which the engineering, biological, and physical sciences are used to study the nature of foods, the causes of deterioration, the principles underlying food processing, and the improvement of foods for the consuming public".

The textbook Food Science defines food science in simpler terms as "the application of basic sciences and engineering to study the physical, chemical, and biochemical nature of foods and the principles of food processing".

Activities of food scientists include the development of new food products, design of processes to produce these foods, choice of packaging materials, shelf-life studies, sensory evaluation of products using survey panels or potential consumers, as well as microbiological and chemical testing.

Food scientists may study more fundamental phenomena that are directly linked to the production of food products and its properties.

Food science brings together multiple scientific disciplines. It incorporates concepts from fields such as microbiology, chemical engineering, and biochemistry.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Science of Food:

The textbook Food Science defines food science in simpler terms as "the application of basic sciences and engineering to study the physical, chemical, and biochemical nature of foods and the principles of food processing".

Activities of food scientists include the development of new food products, design of processes to produce these foods, choice of packaging materials, shelf-life studies, sensory evaluation of products using survey panels or potential consumers, as well as microbiological and chemical testing.

Food scientists may study more fundamental phenomena that are directly linked to the production of food products and its properties.

Food science brings together multiple scientific disciplines. It incorporates concepts from fields such as microbiology, chemical engineering, and biochemistry.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Science of Food:

- Disciplines

- Food Science in the United States

- See also:

Food Allergies including a List of Allergens

YouTube Video: Howard has an allergic reaction to peanuts!

(Big Bang Theory TV Sitcom)

Pictured below: 8 Most Common Food Allergies

Click here for a List of allergens (food and non-food)

A food allergy is an abnormal immune response to food. The signs and symptoms may range from mild to severe. They may include itchiness, swelling of the tongue, vomiting, diarrhea, hives, trouble breathing, or low blood pressure. This typically occurs within minutes to several hours of exposure.

When the symptoms are severe, it is known as anaphylaxis. Food intolerance and food poisoning are separate conditions.

Common foods involved include cow's milk, peanuts, eggs, shellfish, fish, tree nuts, soy, wheat, rice, and fruit. The common allergies vary depending on the country.

Risk factors include a family history of allergies, vitamin D deficiency, obesity, and high levels of cleanliness. Allergies occur when immunoglobulin E(IgE), part of the body's immune system, binds to food molecules. A protein in the food is usually the problem. This triggers the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine.

Diagnosis is usually based on a medical history, elimination diet, skin prick test, blood tests for food-specific IgE antibodies, or oral food challenge.

Early exposure to potential allergens may be protective. Management primarily involves avoiding the food in question and having a plan if exposure occurs. This plan may include giving adrenaline (epinephrine) and wearing medical alert jewelry.

The benefits of allergen immunotherapy for food allergies is unclear, thus is not recommended as of 2015. Some types of food allergies among children resolve with age, including that to milk, eggs, and soy; while others such as to nuts and shellfish typically do not.

In the developed world, about 4% to 8% of people have at least one food allergy. They are more common in children than adults and appear to be increasing in frequency. Male children appear to be more commonly affected than females.

Some allergies more commonly develop early in life, while others typically develop in later life. In developed countries, a large proportion of people believe they have food allergies when they actually do not have them. The declaration of the presence of trace amounts of allergens in foods is not mandatory in any country, with the exception of Brazil.

Signs and symptoms:

Food allergies usually have a fast onset (from seconds to one hour) and may include:

In some cases, however, onset of symptoms may be delayed for hours.

Symptoms of allergies vary from person to person. The amount of food needed to trigger a reaction also varies from person to person.

Serious danger regarding allergies can begin when the respiratory tract or blood circulation is affected. The former can be indicated through wheezing and cyanosis. Poor blood circulation leads to a weak pulse, pale skin and fainting.

A severe case of an allergic reaction, caused by symptoms affecting the respiratory tract and blood circulation, is called anaphylaxis. When symptoms are related to a drop in blood pressure, the person is said to be in anaphylactic shock. Anaphylaxis occurs when IgE antibodies are involved, and areas of the body that are not in direct contact with the food become affected and show symptoms. Those with asthma or an allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, or seafood are at greater risk for anaphylaxis.

Cause:

Although sensitivity levels vary by country, the most common food allergies are allergies to milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, seafood, shellfish, soy, and wheat. These are often referred to as "the big eight".

Allergies to seeds — especially sesame — seem to be increasing in many countries. An example an allergy more common to a particular region is that to rice in East Asia where it forms a large part of the diet.

One of the most common food allergies is a sensitivity to peanuts, a member of the bean family. Peanut allergies may be severe, but children with peanut allergies sometimes outgrow them. Tree nuts, including cashews, Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pistachios, pine nuts, coconuts, and walnuts, are also common allergens. Sufferers may be sensitive to one particular tree nut or to many different ones.

Also, seeds, including sesame seeds and poppy seeds, contain oils where protein is present, which may elicit an allergic reaction.

Egg allergies affect about one in 50 children but are frequently outgrown by children when they reach age five. Typically, the sensitivity is to proteins in the white, rather than the yolk.

Milk from cows, goats, or sheep is another common food allergen, and many sufferers are also unable to tolerate dairy products such as cheese. A small portion of children with a milk allergy, roughly 10%, have a reaction to beef. Beef contains a small amount of protein that is also present in cow's milk.

Seafood is one of the most common sources of food allergens; people may be allergic to proteins found in fish, crustaceans, or shellfish.

Other foods containing allergenic proteins include soy, wheat, fruits, vegetables, maize, spices, synthetic and natural colors, and chemical additives.

Balsam of Peru, which is in various foods, is in the "top five" allergens most commonly causing patch test reactions in people referred to dermatology clinics.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Food Allergies:

A food allergy is an abnormal immune response to food. The signs and symptoms may range from mild to severe. They may include itchiness, swelling of the tongue, vomiting, diarrhea, hives, trouble breathing, or low blood pressure. This typically occurs within minutes to several hours of exposure.

When the symptoms are severe, it is known as anaphylaxis. Food intolerance and food poisoning are separate conditions.

Common foods involved include cow's milk, peanuts, eggs, shellfish, fish, tree nuts, soy, wheat, rice, and fruit. The common allergies vary depending on the country.

Risk factors include a family history of allergies, vitamin D deficiency, obesity, and high levels of cleanliness. Allergies occur when immunoglobulin E(IgE), part of the body's immune system, binds to food molecules. A protein in the food is usually the problem. This triggers the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine.

Diagnosis is usually based on a medical history, elimination diet, skin prick test, blood tests for food-specific IgE antibodies, or oral food challenge.

Early exposure to potential allergens may be protective. Management primarily involves avoiding the food in question and having a plan if exposure occurs. This plan may include giving adrenaline (epinephrine) and wearing medical alert jewelry.

The benefits of allergen immunotherapy for food allergies is unclear, thus is not recommended as of 2015. Some types of food allergies among children resolve with age, including that to milk, eggs, and soy; while others such as to nuts and shellfish typically do not.

In the developed world, about 4% to 8% of people have at least one food allergy. They are more common in children than adults and appear to be increasing in frequency. Male children appear to be more commonly affected than females.

Some allergies more commonly develop early in life, while others typically develop in later life. In developed countries, a large proportion of people believe they have food allergies when they actually do not have them. The declaration of the presence of trace amounts of allergens in foods is not mandatory in any country, with the exception of Brazil.

Signs and symptoms:

Food allergies usually have a fast onset (from seconds to one hour) and may include:

- Rash

- Hives

- Itching of mouth, lips, tongue, throat, eyes, skin, or other areas

- Swelling (angioedema) of lips, tongue, eyelids, or the whole face

- Difficulty swallowing

- Runny or congested nose

- Hoarse voice

- Wheezing and/or shortness of breath

- Diarrhea, abdominal pain, and/or stomach cramps

- Lightheadedness

- Fainting

- Nausea

- Vomiting

In some cases, however, onset of symptoms may be delayed for hours.

Symptoms of allergies vary from person to person. The amount of food needed to trigger a reaction also varies from person to person.

Serious danger regarding allergies can begin when the respiratory tract or blood circulation is affected. The former can be indicated through wheezing and cyanosis. Poor blood circulation leads to a weak pulse, pale skin and fainting.

A severe case of an allergic reaction, caused by symptoms affecting the respiratory tract and blood circulation, is called anaphylaxis. When symptoms are related to a drop in blood pressure, the person is said to be in anaphylactic shock. Anaphylaxis occurs when IgE antibodies are involved, and areas of the body that are not in direct contact with the food become affected and show symptoms. Those with asthma or an allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, or seafood are at greater risk for anaphylaxis.

Cause:

Although sensitivity levels vary by country, the most common food allergies are allergies to milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, seafood, shellfish, soy, and wheat. These are often referred to as "the big eight".

Allergies to seeds — especially sesame — seem to be increasing in many countries. An example an allergy more common to a particular region is that to rice in East Asia where it forms a large part of the diet.

One of the most common food allergies is a sensitivity to peanuts, a member of the bean family. Peanut allergies may be severe, but children with peanut allergies sometimes outgrow them. Tree nuts, including cashews, Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pistachios, pine nuts, coconuts, and walnuts, are also common allergens. Sufferers may be sensitive to one particular tree nut or to many different ones.

Also, seeds, including sesame seeds and poppy seeds, contain oils where protein is present, which may elicit an allergic reaction.

Egg allergies affect about one in 50 children but are frequently outgrown by children when they reach age five. Typically, the sensitivity is to proteins in the white, rather than the yolk.

Milk from cows, goats, or sheep is another common food allergen, and many sufferers are also unable to tolerate dairy products such as cheese. A small portion of children with a milk allergy, roughly 10%, have a reaction to beef. Beef contains a small amount of protein that is also present in cow's milk.

Seafood is one of the most common sources of food allergens; people may be allergic to proteins found in fish, crustaceans, or shellfish.

Other foods containing allergenic proteins include soy, wheat, fruits, vegetables, maize, spices, synthetic and natural colors, and chemical additives.

Balsam of Peru, which is in various foods, is in the "top five" allergens most commonly causing patch test reactions in people referred to dermatology clinics.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Food Allergies:

- Sensitization

- Atopy

- Cross-reactivity

- Pathophysiology

- Diagnosis including Differential diagnosis

- Prevention

- Treatment

- Epidemiology in the United States

- Society and culture

- Research

- SEICAP (Spanish Society of Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology)

Food Preservation

YouTube Video: 10 Food Preservation Tips in 60 Seconds

YouTube Video: How to Freeze Dry Food at Home - Freeze Drying Overview

Pictured below: Home Food Preservation – 10 Ways to Preserve Food at Home

Food preservation prevents the growth of microorganisms (such as yeasts), or other microorganisms (although some methods work by introducing benign bacteria or fungi to the food), as well as slowing the oxidation of fats that cause rancidity.

Food preservation may also include processes that inhibit visual deterioration, such as the enzymatic browning reaction in apples after they are cut during food preparation.

Many processes designed to preserve food involve more than one food preservation method.

Preserving fruit by turning it into jam, for example, involves boiling (to reduce the fruit’s moisture content and to kill bacteria, etc.), sugaring (to prevent their re-growth) and sealing within an airtight jar (to prevent recontamination).

Some traditional methods of preserving food have been shown to have a lower energy input and carbon footprint, when compared to modern methods.

Some methods of food preservation are known to create carcinogens. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classified processed meat, i.e. meat that has undergone salting, curing, fermenting, and smoking, as "carcinogenic to humans".

Maintaining or creating nutritional value, texture and flavor is an important aspect of food preservation.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Food Preservation Techniques:

Food preservation may also include processes that inhibit visual deterioration, such as the enzymatic browning reaction in apples after they are cut during food preparation.

Many processes designed to preserve food involve more than one food preservation method.

Preserving fruit by turning it into jam, for example, involves boiling (to reduce the fruit’s moisture content and to kill bacteria, etc.), sugaring (to prevent their re-growth) and sealing within an airtight jar (to prevent recontamination).

Some traditional methods of preserving food have been shown to have a lower energy input and carbon footprint, when compared to modern methods.

Some methods of food preservation are known to create carcinogens. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classified processed meat, i.e. meat that has undergone salting, curing, fermenting, and smoking, as "carcinogenic to humans".

Maintaining or creating nutritional value, texture and flavor is an important aspect of food preservation.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Food Preservation Techniques:

- Traditional techniques

- Modern industrial techniques

- See also:

- Blast chilling

- Food engineering

- Food microbiology

- Food packaging

- Food rheology

- Food science

- Food spoilage

- Freeze-drying

- Fresherized

- List of dried foods

- List of pickled foods

- List of smoked foods

- Refrigerate after opening

- Shelf life

- Wikimedia Commons has media related to Food preservation.

- Preserving foods ~ from the Clemson Extension Home and Garden Information Center

- National Center for Home Food Preservation

- Home Economics Archive: Tradition, Research, History (HEARTH)

An e-book collection of over 1,000 classic books on home economics spanning 1850 to 1950, created by Cornell University's Mann Library.

Vegan Diet and Vegan Nutrition

YouTube Video: How Your Body Transforms On A Vegan Diet

YouTube Video: Over 10 Years, What a Vegan Diet Did for Me

YouTube Video: How to Prevent Deficiencies on a Vegan Diet

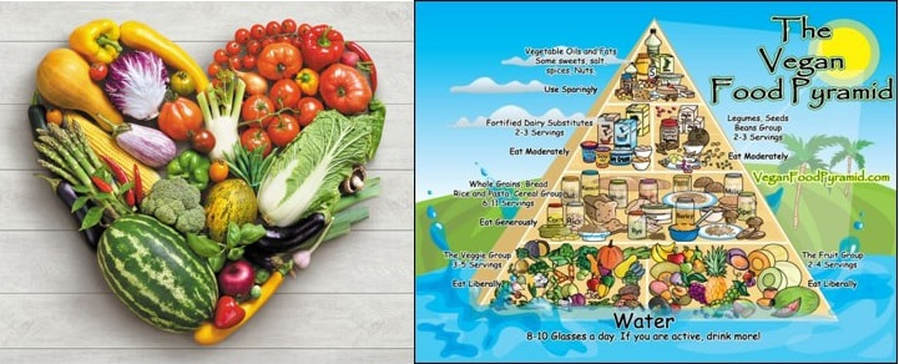

Pictured below:

(L) The right plant-based diet for you by Harvard Health Publishing

(R) 30-Day Go Vegan Challenge courtesy of Vegan ACT (Australia)

Veganism is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal products, particularly in diet, and an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals. A follower of the diet or the philosophy is known as a vegan.

Distinctions may be made between several categories of veganism. Dietary vegans (or strict vegetarians) refrain from consuming animal products, not only meat but also eggs, dairy products and other animal-derived substances.

The term ethical vegan is often applied to those who not only follow a vegan diet but extend the philosophy into other areas of their lives, and oppose the use of animals for any purpose.

Another term is environmental veganism, which refers to the avoidance of animal products on the premise that the industrial farming of animals is environmentally damaging and unsustainable.

Some reviews have shown that some people who eat vegan diets have less chronic disease, including heart disease, than people who do not follow a restrictive diet. They are regarded as appropriate for all stages of life including during infancy and pregnancy by the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the British Dietetic Association.

The German Society for Nutrition does not recommend vegan diets for children or adolescents, or during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals; and lower in dietary energy, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12. Unbalanced vegan diets may lead to nutritional deficiencies that nullify any beneficial effects and may cause serious health issues.

Some of these deficiencies can only be prevented through the choice of fortified foods or the regular intake of dietary supplements. Vitamin B12 supplementation is especially important because its deficiency causes blood disorders and potentially irreversible neurological damage.

Donald Watson coined the term vegan in 1944 when he co-founded the Vegan Society in England. At first he used it to mean "non-dairy vegetarian", but from 1951 the Society defined it as "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals". Interest in veganism increased in the 2010s, especially in the latter half. More vegan stores opened and vegan options became increasingly available in supermarkets and restaurants in many countries.

Click on any of the following for more about a Vegan Diet:

Vegan Nutrition:

Vegan nutrition refers to the nutritional and human health aspects of vegan diets.

While a well-planned, balanced vegan diet is suitable to meet all recommendations for nutrients in every stage of human life, improperly planned vegan diets may be deficient in vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, zinc, riboflavin (vitamin B2), and the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Vegan Nutrition:

Distinctions may be made between several categories of veganism. Dietary vegans (or strict vegetarians) refrain from consuming animal products, not only meat but also eggs, dairy products and other animal-derived substances.

The term ethical vegan is often applied to those who not only follow a vegan diet but extend the philosophy into other areas of their lives, and oppose the use of animals for any purpose.

Another term is environmental veganism, which refers to the avoidance of animal products on the premise that the industrial farming of animals is environmentally damaging and unsustainable.

Some reviews have shown that some people who eat vegan diets have less chronic disease, including heart disease, than people who do not follow a restrictive diet. They are regarded as appropriate for all stages of life including during infancy and pregnancy by the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the British Dietetic Association.

The German Society for Nutrition does not recommend vegan diets for children or adolescents, or during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals; and lower in dietary energy, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12. Unbalanced vegan diets may lead to nutritional deficiencies that nullify any beneficial effects and may cause serious health issues.

Some of these deficiencies can only be prevented through the choice of fortified foods or the regular intake of dietary supplements. Vitamin B12 supplementation is especially important because its deficiency causes blood disorders and potentially irreversible neurological damage.

Donald Watson coined the term vegan in 1944 when he co-founded the Vegan Society in England. At first he used it to mean "non-dairy vegetarian", but from 1951 the Society defined it as "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals". Interest in veganism increased in the 2010s, especially in the latter half. More vegan stores opened and vegan options became increasingly available in supermarkets and restaurants in many countries.

Click on any of the following for more about a Vegan Diet:

- Origins

- Increasing interest

- Veganism by country

- Animal products

- Vegan diet

- Personal items

- Philosophy

- Symbols

- The Vegan Society

Vegan Nutrition:

Vegan nutrition refers to the nutritional and human health aspects of vegan diets.

While a well-planned, balanced vegan diet is suitable to meet all recommendations for nutrients in every stage of human life, improperly planned vegan diets may be deficient in vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, zinc, riboflavin (vitamin B2), and the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Vegan Nutrition:

Organic Foods and Whole Foods

YouTube Video: Why Organic, Sustainable Farming Matters | Portrait of a Farmer

YouTube Video: This is "The Whole Foods™ Diet" l Whole Foods Market

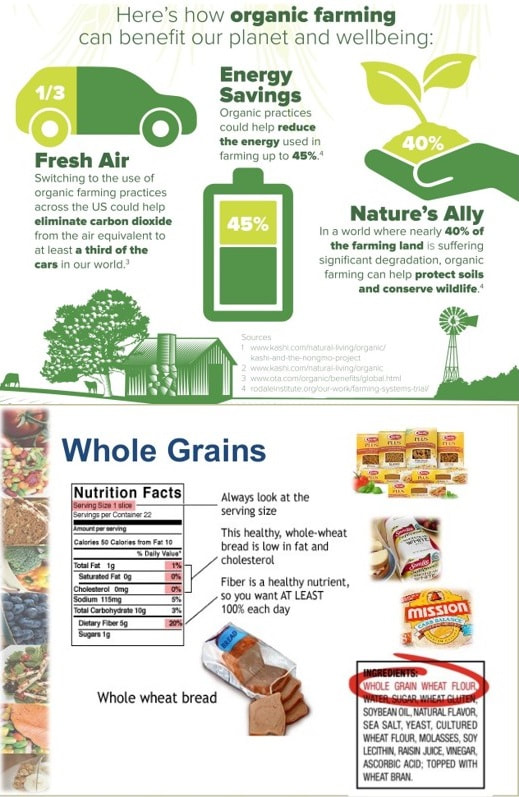

Pictured below:

(Top) Will Organic Farming Replace Conventional Farming?

(Bottom) Fighting Cancer with Food and Activity (Slide Show)

Organic Foods:

Organic food is food produced by methods that comply with the standards of organic farming. Standards vary worldwide, but organic farming in general features practices that strive to cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.

Organizations regulating organic products may restrict the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers in farming. In general, organic foods are also usually not processed using irradiation, industrial solvents or synthetic food additives.

Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and many other countries require producers to obtain special certification in order to market food as organic within their borders. In the context of these regulations, organic food is produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by regional organizations, national governments and international organizations.

Although the produce of kitchen gardens may be organic, selling food with an organic label is regulated by governmental food safety authorities, such as the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) or European Commission (EC).

Fertilizing and the use of pesticides in conventional farming has caused, and is causing, enormous damage worldwide to local ecosystems, biodiversity, groundwater and drinking water supplies, and sometimes farmer health and fertility. These environmental, economic and health issues are all minimized or avoided completely in organic farming.

From a consumers perspective, there is not sufficient evidence in scientific and medical literature to support claims that organic food is safer or healthier to eat than conventionally grown food.

While there may be some differences in the nutrient and antinutrient contents of organically- and conventionally-produced food, the variable nature of food production and handling makes it difficult to generalize results. Claims that organic food tastes better are generally not supported by tests.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Organic Foods:

Whole Foods:

Whole foods are plant foods that are unprocessed and unrefined, or processed and refined as little as possible, before being consumed. Examples of whole foods include whole grains, tubers, legumes, fruits, vegetables.

There is some confusion over the usage of the term surrounding the inclusion of certain foods, in particular animal foods. The modern usage of the term whole foods diet is now widely synonymous with "whole foods plant-based diet" with animal products, oil and salt no longer constituting whole foods.

The earliest use of the term in the post-industrial age appears to be in 1946 in The Farmer, a quarterly magazine published and edited from his farm by F. Newman Turner, a writer and pioneering organic farmer. The magazine sponsored the establishment of the Producer Consumer Whole Food Society Ltd, with Newman Turner as president and Derek Randal as vice-president.

Whole food was defined as "mature produce of field, orchard, or garden without subtraction, addition, or alteration grown from seed without chemical dressing, in fertile soil manured solely with animal and vegetable wastes, and composts therefrom, and ground, raw rock and without chemical manures, sprays, or insecticides," having intent to connect suppliers and the growing public demand for such food.

Such diets are rich in whole and unrefined foods, like whole grains, dark green and yellow/orange-fleshed vegetables and fruits, legumes, nuts and seeds.

See also:

Organic food is food produced by methods that comply with the standards of organic farming. Standards vary worldwide, but organic farming in general features practices that strive to cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.

Organizations regulating organic products may restrict the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers in farming. In general, organic foods are also usually not processed using irradiation, industrial solvents or synthetic food additives.

Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and many other countries require producers to obtain special certification in order to market food as organic within their borders. In the context of these regulations, organic food is produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by regional organizations, national governments and international organizations.

Although the produce of kitchen gardens may be organic, selling food with an organic label is regulated by governmental food safety authorities, such as the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) or European Commission (EC).

Fertilizing and the use of pesticides in conventional farming has caused, and is causing, enormous damage worldwide to local ecosystems, biodiversity, groundwater and drinking water supplies, and sometimes farmer health and fertility. These environmental, economic and health issues are all minimized or avoided completely in organic farming.

From a consumers perspective, there is not sufficient evidence in scientific and medical literature to support claims that organic food is safer or healthier to eat than conventionally grown food.

While there may be some differences in the nutrient and antinutrient contents of organically- and conventionally-produced food, the variable nature of food production and handling makes it difficult to generalize results. Claims that organic food tastes better are generally not supported by tests.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Organic Foods:

- Meaning and origin of the term including its Legal definition

- Public perception including Taste

- Chemical composition

- Organic meat production requirements in the United States

- Health and safety

- Economics in North America

- See also:

- Agroecology

- Genetically modified food

- List of organic food topics

- Natural foods

- Organic beans

- Organic clothing

- Organic farming

- Permaculture

- Soil Association

- Whole foods

- Organic food culture

- A World Map of Organic Agriculture

- USDA National Organic Program Responsible for administering organic food production & labeling standards in the United States

- UK Organic certification and standards

Whole Foods:

Whole foods are plant foods that are unprocessed and unrefined, or processed and refined as little as possible, before being consumed. Examples of whole foods include whole grains, tubers, legumes, fruits, vegetables.

There is some confusion over the usage of the term surrounding the inclusion of certain foods, in particular animal foods. The modern usage of the term whole foods diet is now widely synonymous with "whole foods plant-based diet" with animal products, oil and salt no longer constituting whole foods.

The earliest use of the term in the post-industrial age appears to be in 1946 in The Farmer, a quarterly magazine published and edited from his farm by F. Newman Turner, a writer and pioneering organic farmer. The magazine sponsored the establishment of the Producer Consumer Whole Food Society Ltd, with Newman Turner as president and Derek Randal as vice-president.

Whole food was defined as "mature produce of field, orchard, or garden without subtraction, addition, or alteration grown from seed without chemical dressing, in fertile soil manured solely with animal and vegetable wastes, and composts therefrom, and ground, raw rock and without chemical manures, sprays, or insecticides," having intent to connect suppliers and the growing public demand for such food.

Such diets are rich in whole and unrefined foods, like whole grains, dark green and yellow/orange-fleshed vegetables and fruits, legumes, nuts and seeds.

See also:

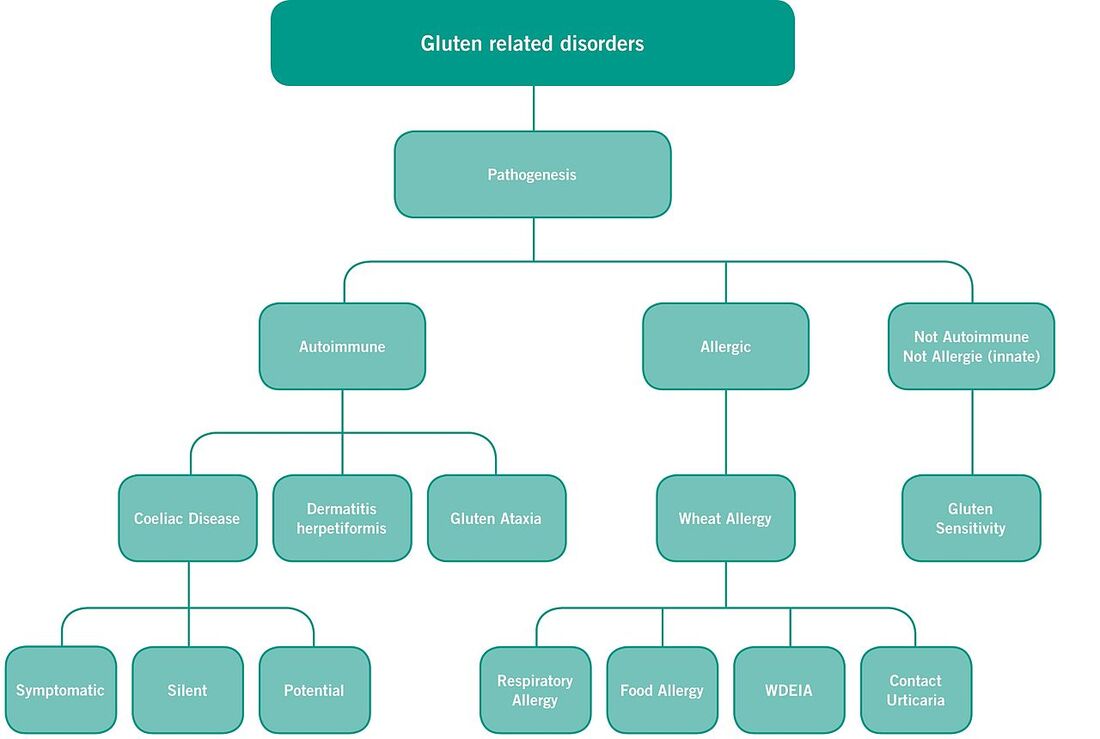

Gluten-related Disorders

- YouTube Video: Celiac Disease and Gluten Disorders in Children

- YouTube Video: Daily bread -- Can any human body handle gluten? | Dr. Rodney Ford | TEDxTauranga

- YouTube Video: Everything You Need to Know About Gluten

Gluten-related disorders is the term for the diseases triggered by gluten, including celiac disease (CD), non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), gluten ataxia, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) and wheat allergy.

The umbrella category has also been referred to as gluten intolerance, though a multi-disciplinary physician-led study, based in part on the 2011 International Coeliac Disease Symposium, concluded that the use of this term should be avoided due to a lack of specificity.

Gluten is a group of proteins, such as prolamins and glutelins, stored with starch in the endosperm of various cereal (grass) grains.

As of 2017, gluten-related disorders were increasing in frequency in different geographic areas. The increase might be explained by the popularity of the Western diet, the expanded reach of the Mediterranean diet (which also includes grains with gluten), the growing replacement of rice by wheat in many countries, the development in recent years of new types of wheat with a higher amount of cytotoxic gluten peptides, and the higher content of gluten in bread and bakery products, due to the reduction of dough fermentation time.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Gluten-related disorders: