Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Covers all activities of

The United States Military,

as well as the CIA, Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security; memorials, cemeteries, medals and other awards, veteran affairs including medical care (e.g. PTSD), future job training, recruiting, retirement, major wars including war on terrorism, and more.

See Also "Greatest Americans"

Military including the United States Armed Forces

YouTube Musical Video: United States Military Tribute - - "My Sacrifice" by Creed

Pictured: LEFT to RIGHT: US B-2 Spirit bomber; Statue of Liberty with Air Force Jets Fly-over; United States Military Academy at West Point

Military in General:

The military, also called the armed forces, are forces authorized to use deadly force, and weapons, to support the interests of the state and some or all of its citizens. The task of the military is usually defined as defense of the state and its citizens, and the prosecution of war against another state.

The military may also have additional sanctioned and non-sanctioned functions within a society, including,

The military can also function as a discrete subculture within a larger civil society, through the development of separate infrastructures, which may include housing, schools, utilities, food production and banking.

The United States Armed Forces:

The federal armed forces of the United States consist of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard.

The President of the United States is the military's overall head, and helps form military policy with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), a federal executive department, acting as the principal organ by which military policy is carried out.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged as a result of victory in the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War.

Even so, the Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force. It played an important role in the American Civil War, where leading generals on both sides were picked from members of the United States military.

Not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established. The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the Cold War's onset, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of number of personnel. It draws its personnel from a large pool of paid volunteers; although conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972.

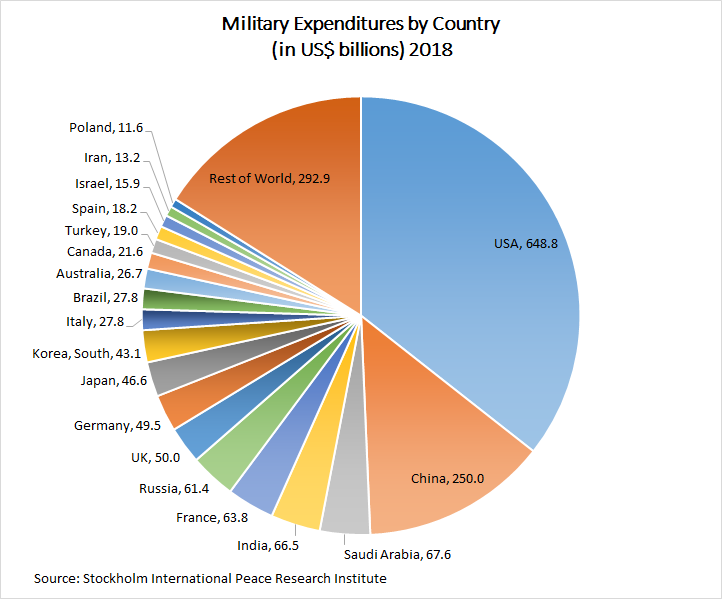

As of 2016, the United States spends about $580.3 billion annually to fund its military forces and Overseas Contingency Operations.

Put together, the United States constitutes roughly 39 percent of the world's military expenditures. For the period 2010–14, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that the United States was the world's largest exporter of major arms, accounting for 31 per cent of global shares.

The United States was also the world's eighth largest importer of major weapons for the same period. The U.S. Armed Forces has significant capabilities in both defense and power projection due to its large budget, resulting in advanced and powerful equipment, and its widespread deployment of force around the world, including about 800 military bases in foreign locations.

For Further Amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

The military, also called the armed forces, are forces authorized to use deadly force, and weapons, to support the interests of the state and some or all of its citizens. The task of the military is usually defined as defense of the state and its citizens, and the prosecution of war against another state.

The military may also have additional sanctioned and non-sanctioned functions within a society, including,

- the promotion of a political agenda,

- protecting corporate economic interests,

- internal population control,

- construction,

- emergency services,

- social ceremonies,

- and guarding important areas.

The military can also function as a discrete subculture within a larger civil society, through the development of separate infrastructures, which may include housing, schools, utilities, food production and banking.

The United States Armed Forces:

The federal armed forces of the United States consist of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard.

The President of the United States is the military's overall head, and helps form military policy with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), a federal executive department, acting as the principal organ by which military policy is carried out.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged as a result of victory in the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War.

Even so, the Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force. It played an important role in the American Civil War, where leading generals on both sides were picked from members of the United States military.

Not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established. The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the Cold War's onset, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of number of personnel. It draws its personnel from a large pool of paid volunteers; although conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972.

As of 2016, the United States spends about $580.3 billion annually to fund its military forces and Overseas Contingency Operations.

Put together, the United States constitutes roughly 39 percent of the world's military expenditures. For the period 2010–14, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that the United States was the world's largest exporter of major arms, accounting for 31 per cent of global shares.

The United States was also the world's eighth largest importer of major weapons for the same period. The U.S. Armed Forces has significant capabilities in both defense and power projection due to its large budget, resulting in advanced and powerful equipment, and its widespread deployment of force around the world, including about 800 military bases in foreign locations.

For Further Amplification, click on any of the following hyperlinks:

- History

- Command structure

- Budget

- Personnel

- Order of precedence

- See also:

- Awards and decorations of the United States military

- Full-spectrum dominance

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of currently active United States military land vehicles

- List of currently active United States military watercraft

- Military expression

- Military justice

- National Guard

- Public opinion of the military

- Servicemembers' Group Life Insurance

- Sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States military

- State Defense Force

- TRICARE – Health care plan for the U.S. uniformed services

- United States military casualties of war

- United States military veteran suicide

- United States Service academies

- Women in the United States Army

- Women in the United States Marines

- Women in the United States Navy

- Women in the United States Air Force

- Women in the United States Coast Guard

United States Department of Defense,

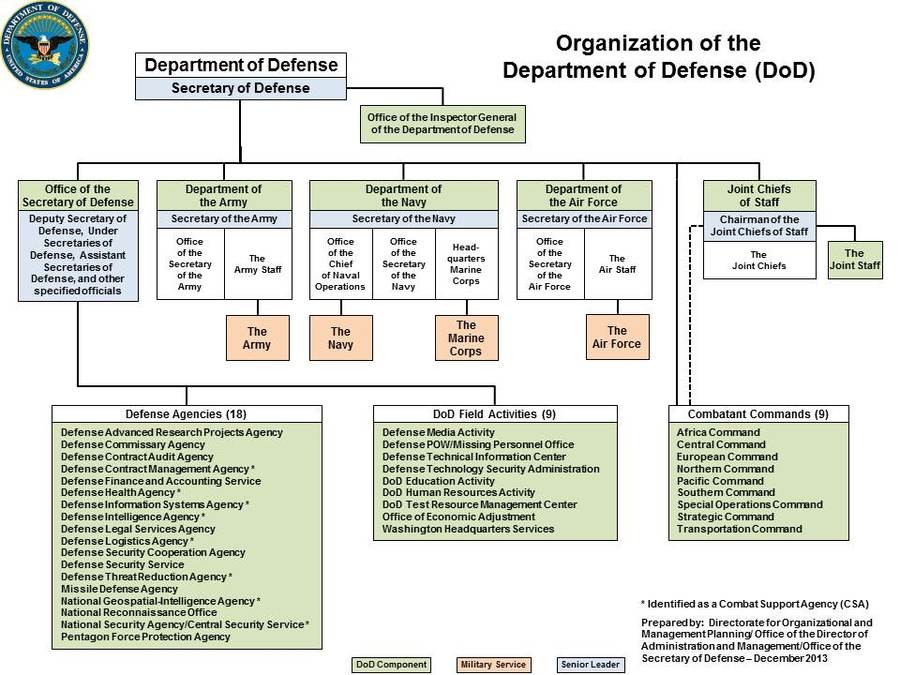

Pictured: Organizational Chart for the US. Department of Defense

- including U.S Central Command;

- as well as a List of the Major U.S. Defense Contractors.

Pictured: Organizational Chart for the US. Department of Defense

Click here for a list of Defense Contractors serving the United States Defense Department.

The Department of Defense (DoD) is an executive branch department of the federal government of the United States charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government concerned directly with national security and the United States Armed Forces.

The department is the largest employer in the world, with nearly 1.3 million active duty servicemen and women as of 2016. Adding to its employees are over 826,000 National Guardsmen and Reservists from the four services, and over 742,000 civilians bringing the total to over 2.8 million employees.

Headquartered at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., the DoD's stated mission is ...to provide a lethal Joint Force to defend the security of our country and sustain American influence abroad.

The Department of Defense is headed by the Secretary of Defense, a cabinet-level head who reports directly to the President of the United States.

Beneath the Department of Defense are three subordinate military departments:

In addition, four national intelligence services are subordinate to the Department of Defense:

Other Defense Agencies include:

All of the above are under the command of the Secretary of Defense. Military operations are managed by ten regional or functional Unified combatant commands.

The Department of Defense also operates several joint services schools, including the National Defense University (NDU) and the National War College (NWC).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Department of Defense:

U.S Central Command

The United States Central Command (USCENTCOM or CENTCOM) is a theater-level Unified Combatant Command of the U.S. Department of Defense. It was established in 1983, taking over the 1980 Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) responsibilities.

The CENTCOM Area of Responsibility (AOR) includes countries in the West Asia, parts of North Africa, and Central Asia, most notably Afghanistan and Iraq. CENTCOM has been the main American presence in many military operations, including the Persian Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm, 1991), the War in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001–2014), and the Iraq War (Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003–2011).

As of 2015, CENTCOM forces are deployed primarily in Afghanistan (Operation Resolute Support, 2015–present), Iraq and Syria (Operation Inherent Resolve, 2014–present) in supporting and advise-and-assist roles.

As of 1 September 2016, CENTCOM's commander was General Joseph Votel, U.S. Army.

Of all six American regional unified combatant commands, CENTCOM is among the three with headquarters outside its area of operations (the other two being USAFRICOM and USSOUTHCOM).

CENTCOM's main headquarters is located at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida. A forward headquarters was established in 2002 at Camp As Sayliyah in Doha, Qatar, which in 2009 transitioned to a forward headquarters at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

The United States Central Command (USCENTCOM or CENTCOM) is a theater-level Unified Combatant Command of the U.S. Department of Defense. It was established in 1983, taking over the 1980 Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) responsibilities.

The CENTCOM Area of Responsibility (AOR) includes countries in the West Asia, parts of North Africa, and Central Asia, most notably Afghanistan and Iraq.

CENTCOM has been the main American presence in many military operations, including :

As of 2015, CENTCOM forces are deployed primarily in Afghanistan (Operation Resolute Support, 2015–present), Iraq and Syria (Operation Inherent Resolve, 2014–present) in supporting and advise-and-assist roles.

As of 1 September 2016, CENTCOM's commander was General Joseph Votel, U.S. Army.

Of all six American regional unified combatant commands, CENTCOM is among the three with headquarters outside its area of operations (the other two being USAFRICOM and USSOUTHCOM).

CENTCOM's main headquarters is located at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida. A forward headquarters was established in 2002 at Camp As Sayliyah in Doha, Qatar, which in 2009 transitioned to a forward headquarters at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Central Command:

The Department of Defense (DoD) is an executive branch department of the federal government of the United States charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government concerned directly with national security and the United States Armed Forces.

The department is the largest employer in the world, with nearly 1.3 million active duty servicemen and women as of 2016. Adding to its employees are over 826,000 National Guardsmen and Reservists from the four services, and over 742,000 civilians bringing the total to over 2.8 million employees.

Headquartered at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., the DoD's stated mission is ...to provide a lethal Joint Force to defend the security of our country and sustain American influence abroad.

The Department of Defense is headed by the Secretary of Defense, a cabinet-level head who reports directly to the President of the United States.

Beneath the Department of Defense are three subordinate military departments:

- the United States Department of the Army,

- the United States Department of the Navy,

- and the United States Department of the Air Force.

In addition, four national intelligence services are subordinate to the Department of Defense:

- the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA),

- the National Security Agency (NSA),

- the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA),

- and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO).

Other Defense Agencies include:

- the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA),

- the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA),

- the Missile Defense Agency (MDA),

- the Defense Health Agency (DHA),

- Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA),

- the Defense Security Service (DSS),

- and the Pentagon Force Protection Agency (PFPA),

All of the above are under the command of the Secretary of Defense. Military operations are managed by ten regional or functional Unified combatant commands.

The Department of Defense also operates several joint services schools, including the National Defense University (NDU) and the National War College (NWC).

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Department of Defense:

- History

- Organizational structure

- Budget

- Criticism

- Energy use

- Freedom of Information Act processing performance

- Related legislation

- See also:

- Official website

- Department of Defense in the Federal Register

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Budget and Financial Management Policy

- Department of Defense IA Policy Chart

- Works by United States Department of Defense at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about United States Department of Defense at Internet Archive

- Department of Defense Collection on the Internet Archive

- Arms industry

- List of United States military bases

- Military–industrial complex

- Nuclear weapons

- Private military company

- Title 32 of the Code of Federal Regulations

- Warrior Games

- JADE (planning system)

- Global Command and Control System

U.S Central Command

The United States Central Command (USCENTCOM or CENTCOM) is a theater-level Unified Combatant Command of the U.S. Department of Defense. It was established in 1983, taking over the 1980 Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) responsibilities.

The CENTCOM Area of Responsibility (AOR) includes countries in the West Asia, parts of North Africa, and Central Asia, most notably Afghanistan and Iraq. CENTCOM has been the main American presence in many military operations, including the Persian Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm, 1991), the War in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001–2014), and the Iraq War (Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003–2011).

As of 2015, CENTCOM forces are deployed primarily in Afghanistan (Operation Resolute Support, 2015–present), Iraq and Syria (Operation Inherent Resolve, 2014–present) in supporting and advise-and-assist roles.

As of 1 September 2016, CENTCOM's commander was General Joseph Votel, U.S. Army.

Of all six American regional unified combatant commands, CENTCOM is among the three with headquarters outside its area of operations (the other two being USAFRICOM and USSOUTHCOM).

CENTCOM's main headquarters is located at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida. A forward headquarters was established in 2002 at Camp As Sayliyah in Doha, Qatar, which in 2009 transitioned to a forward headquarters at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

The United States Central Command (USCENTCOM or CENTCOM) is a theater-level Unified Combatant Command of the U.S. Department of Defense. It was established in 1983, taking over the 1980 Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) responsibilities.

The CENTCOM Area of Responsibility (AOR) includes countries in the West Asia, parts of North Africa, and Central Asia, most notably Afghanistan and Iraq.

CENTCOM has been the main American presence in many military operations, including :

- the Persian Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm, 1991),

- the War in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001–2014),

- and the Iraq War (Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003–2011).

As of 2015, CENTCOM forces are deployed primarily in Afghanistan (Operation Resolute Support, 2015–present), Iraq and Syria (Operation Inherent Resolve, 2014–present) in supporting and advise-and-assist roles.

As of 1 September 2016, CENTCOM's commander was General Joseph Votel, U.S. Army.

Of all six American regional unified combatant commands, CENTCOM is among the three with headquarters outside its area of operations (the other two being USAFRICOM and USSOUTHCOM).

CENTCOM's main headquarters is located at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida. A forward headquarters was established in 2002 at Camp As Sayliyah in Doha, Qatar, which in 2009 transitioned to a forward headquarters at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Central Command:

- History

- Structure including War planning

- Geographic scope

- Commanders

- See also:

- U.S. Central Command official website

- Multi-National Force – Iraq.com mnf-iraq.com (in English)

- Spiegel, Peter (5 January 2007). "Naming New Generals A Key Step In Shift On Iraq". Los Angeles Times.

- Foreign Policy, Pentagon Ups the Ante in Syria Fight

- http://www.armytimes.com/story/military/pentagon/2014/12/30/iraq-1st-infantry-funk/21062071/ - Combined Joint Forces Land Component Command - Iraq

- Strategic Army Corps

United States Department of Homeland Security

YouTube Video:"We are DHS!"

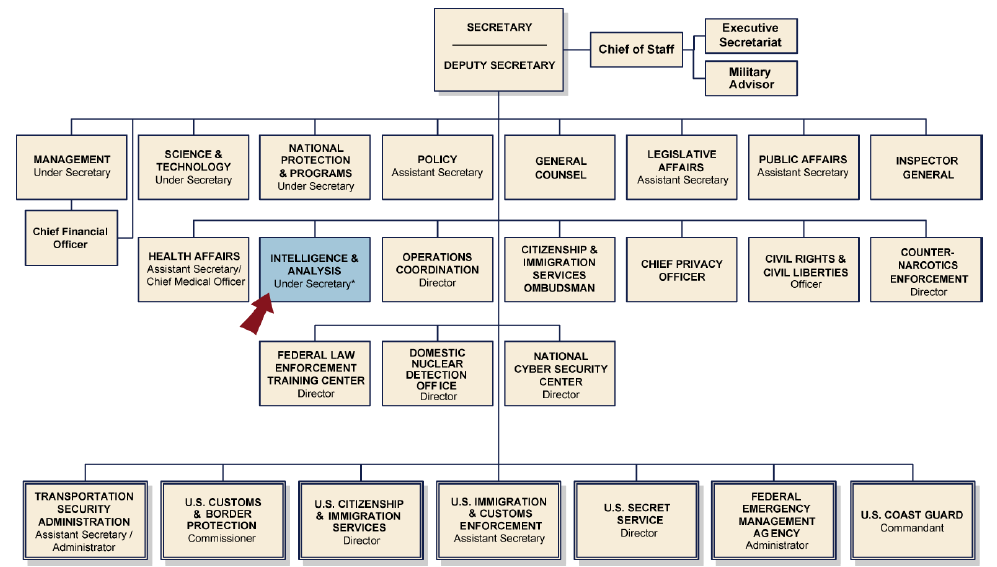

Pictured below: Organizational Chart for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

YouTube Video:"We are DHS!"

Pictured below: Organizational Chart for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is a cabinet department of the United States federal government with responsibilities in public security, roughly comparable to the interior or home ministries of other countries.

Its stated missions involve anti-terrorism, border security, immigration and customs, cyber security, and disaster prevention and management. It was created in response to the September 11 attacks and is the youngest U.S. cabinet department.

In fiscal year 2017, it was allocated a net discretionary budget of $40.6 billion. With more than 240,000 employees, DHS is the third largest Cabinet department, after the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs.

Homeland security policy is coordinated at the White House by the Homeland Security Council. Other agencies with significant homeland security responsibilities include the Departments of Health and Human Services, Justice, and Energy.

The former Secretary, John F. Kelly, was replaced by Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen on December 5, 2017.

Function:

Whereas the Department of Defense is charged with military actions abroad, the Department of Homeland Security works in the civilian sphere to protect the United States within, at, and outside its borders.

Its stated goal is to prepare for, prevent, and respond to domestic emergencies, particularly terrorism. On March 1, 2003, DHS absorbed the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and assumed its duties. In doing so, it divided the enforcement and services functions into two separate and new agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Citizenship and Immigration Services.

The investigative divisions and intelligence gathering units of the INS and Customs Service were merged forming Homeland Security Investigations.

Additionally, the border enforcement functions of the INS, including the U.S. Border Patrol, the U.S. Customs Service, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service were consolidated into a new agency under DHS: U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The Federal Protective Service falls under the National Protection and Programs Directorate.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The U.S. Department of Homeland Security:

Its stated missions involve anti-terrorism, border security, immigration and customs, cyber security, and disaster prevention and management. It was created in response to the September 11 attacks and is the youngest U.S. cabinet department.

In fiscal year 2017, it was allocated a net discretionary budget of $40.6 billion. With more than 240,000 employees, DHS is the third largest Cabinet department, after the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs.

Homeland security policy is coordinated at the White House by the Homeland Security Council. Other agencies with significant homeland security responsibilities include the Departments of Health and Human Services, Justice, and Energy.

The former Secretary, John F. Kelly, was replaced by Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen on December 5, 2017.

Function:

Whereas the Department of Defense is charged with military actions abroad, the Department of Homeland Security works in the civilian sphere to protect the United States within, at, and outside its borders.

Its stated goal is to prepare for, prevent, and respond to domestic emergencies, particularly terrorism. On March 1, 2003, DHS absorbed the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and assumed its duties. In doing so, it divided the enforcement and services functions into two separate and new agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Citizenship and Immigration Services.

The investigative divisions and intelligence gathering units of the INS and Customs Service were merged forming Homeland Security Investigations.

Additionally, the border enforcement functions of the INS, including the U.S. Border Patrol, the U.S. Customs Service, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service were consolidated into a new agency under DHS: U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The Federal Protective Service falls under the National Protection and Programs Directorate.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about The U.S. Department of Homeland Security:

- Structure

- National Terrorism Advisory System

- History

- Seal

- Headquarters

- Disaster preparedness and response

- Cyber-security

- Expenditures

- Criticism

- See also:

- Official website

- DHS in the Federal Register

- Container Security Initiative

- E-Verify

- Electronic System for Travel Authorization

- Homeland

- Emergency Management Institute

- Homeland Security USA

- Homeland security grant

- List of state departments of homeland security

- National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), Ft Detrick, MD

- National Interoperability Field Operations Guide

- National Strategy for Homeland Security

- Project Hostile Intent

- Public Safety Canada

- Shadow Wolves

- Terrorism in the United States

- United States visas

- United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT)

- Visa Waiver Program

United States Air Force

YouTube Video: F 16 Fighter Pilots over Afghanistan

YouTube Video: Awesome Air Show by U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds With F-16 Fighting Falcon

Pictured below: First F-35 Lightning II of the 33rd Fighter Wing arrives at Eglin AFB

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the aerial and space warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the five branches of the United States Armed Forces, and one of the seven American uniformed services.

Initially established as a part of the United States Army on 1 August 1907, the USAF was formed as a separate branch of the U.S. Armed Forces on 18 September 1947 with the passing of the National Security Act of 1947. It is the youngest branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, and the fourth in order of precedence.

The USAF is the largest and most technologically advanced air force in the world. The Air Force articulates its core missions as:

The U.S. Air Force is a military service branch organized within the Department of the Air Force, one of the three military departments of the Department of Defense (see above). The Air Force, through the Department of the Air Force, is headed by the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, who reports to the Secretary of Defense, and is appointed by the President with Senate confirmation.

The highest-ranking military officer in the Air Force is the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, who exercises supervision over Air Force units and serves as one of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Air Force forces are assigned, as directed by the Secretary of Defense, to the combatant commanders, and neither the Secretary of the Air Force nor the Chief of Staff of the Air Force have operational command authority over them.

Along with conducting independent air and space operations, the U.S. Air Force provides air support for land and naval forces and aids in the recovery of troops in the field. As of 2017, the service operates more than 5,369 military aircraft, 406 ICBMs and 170 military satellites.

It has a $161 billion budget and is the second largest service branch, with 318,415 active duty personnel, 140,169 civilian personnel, 69,200 Air Force Reserve personnel, and 105,700 Air National Guard personnel.

Mission:

According to the National Security Act of 1947 (61 Stat. 502), which created the USAF:

In general the United States Air Force shall include aviation forces both combat and service not otherwise assigned.

It shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained offensive and defensive air operations.

The Air Force shall be responsible for the preparation of the air forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Air Force to meet the needs of war.§8062 of Title 10 US Code defines the purpose of the USAF as:

The stated mission of the USAF today is to "fly, fight, and win in air, space, and cyberspace".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Air Force:

Initially established as a part of the United States Army on 1 August 1907, the USAF was formed as a separate branch of the U.S. Armed Forces on 18 September 1947 with the passing of the National Security Act of 1947. It is the youngest branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, and the fourth in order of precedence.

The USAF is the largest and most technologically advanced air force in the world. The Air Force articulates its core missions as:

- air and space superiority,

- global integrated ISR,

- rapid global mobility,

- global strike, and command and control.

The U.S. Air Force is a military service branch organized within the Department of the Air Force, one of the three military departments of the Department of Defense (see above). The Air Force, through the Department of the Air Force, is headed by the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, who reports to the Secretary of Defense, and is appointed by the President with Senate confirmation.

The highest-ranking military officer in the Air Force is the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, who exercises supervision over Air Force units and serves as one of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Air Force forces are assigned, as directed by the Secretary of Defense, to the combatant commanders, and neither the Secretary of the Air Force nor the Chief of Staff of the Air Force have operational command authority over them.

Along with conducting independent air and space operations, the U.S. Air Force provides air support for land and naval forces and aids in the recovery of troops in the field. As of 2017, the service operates more than 5,369 military aircraft, 406 ICBMs and 170 military satellites.

It has a $161 billion budget and is the second largest service branch, with 318,415 active duty personnel, 140,169 civilian personnel, 69,200 Air Force Reserve personnel, and 105,700 Air National Guard personnel.

Mission:

According to the National Security Act of 1947 (61 Stat. 502), which created the USAF:

In general the United States Air Force shall include aviation forces both combat and service not otherwise assigned.

It shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained offensive and defensive air operations.

The Air Force shall be responsible for the preparation of the air forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Air Force to meet the needs of war.§8062 of Title 10 US Code defines the purpose of the USAF as:

- to preserve the peace and security, and provide for the defense, of the United States, the Territories, Commonwealths, and possessions, and any areas occupied by the United States;

- to support national policy;

- to implement national objectives;

- to overcome any nations responsible for aggressive acts that imperil the peace and security of the United States.

The stated mission of the USAF today is to "fly, fight, and win in air, space, and cyberspace".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Air Force:

- Vision

- Core missions

- History

- Organization

- Personnel

- Aircraft inventory

- Culture

- Air Force Academy

- See also:

- Official:

- Other:

- Searchable database of Air Force historical reports

- USAF emblems

- Members of the US Air Force on RallyPoint

- Aircraft Investment Plan, Fiscal Years (FY) 2011–2040, Submitted with the FY 2011 Budget

- National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force: Report to the President and the Congress of the United States

- Works by or about United States Air Force at Internet Archive

- Airman's Creed

- Air Force Association

- Air Force Combat Ammunition Center

- Air Force Knowledge Now

- Company Grade Officers' Council

- Department of the Air Force Police

- Future military aircraft of the United States

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of United States Air Force installations

- List of United States Airmen

- List of U.S. Air Force acronyms and expressions

- National Museum of the United States Air Force

- Structure of the United States Air Force

- United States Air Force Band

- United States Air Force Chaplain Corps

- United States Air Force Combat Control Team

- United States Air Force Medical Service

- United States Air Force Thunderbirds

- Women in the United States Air Force

United States Army

YouTube Video: Tribute to Women in the U.S. Army

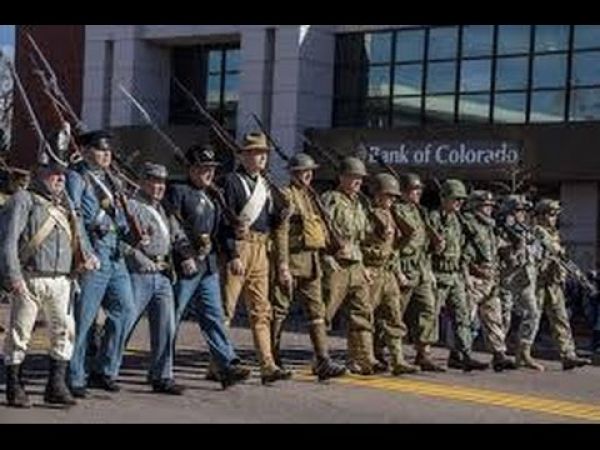

Pictured below: 23 distinct styles of dress which represents and honors the American Patriots and Pioneers who helped found the United States and the U.S. Army Soldiers who served while wearing these uniforms, weapons, and accouterments — during some of the most well-known and significant conflicts since the first militia musters of the 17th century. Shot in 4K and featuring Mark Aaron as "the soldier

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the seven uniformed services of the United States, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution, Article 2, Section 2, Clause 1] and United States Code, Title 10, Subtitle B, Chapter 301, Section 3001].

As the oldest and most senior branch of the U.S. military in order of precedence, the modern U.S. Army has its roots in the Continental Army, which was formed (14 June 1775) to fight the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)—before the United States of America was established as a country.

After the Revolutionary War, the Congress of the Confederation created the United States Army on 3 June 1784 to replace the disbanded Continental Army. The United States Army considers itself descended from the Continental Army, and dates its institutional inception from the origin of that armed force in 1775.

As a uniformed military service, the U.S. Army is part of the Department of the Army, which is one of the three military departments of the Department of Defense. The U.S. Army is headed by a civilian senior appointed civil servant, the Secretary of the Army (SECARMY) and by a chief military officer, the Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) who is also a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

It is the largest military branch, and in the fiscal year 2017, the projected end strength for the Regular Army (USA) was 476,000 soldiers; the Army National Guard (ARNG) had 343,000 soldiers and the United States Army Reserve (USAR) had 199,000 soldiers; the combined-component strength of the U.S. Army was 1,018,000 soldiers.[4]

As a branch of the armed forces, the mission of the U.S. Army is "to fight and win our Nation's wars, by providing prompt, sustained, land dominance, across the full range of military operations and the spectrum of conflict, in support of combatant commanders". The branch participates in conflicts worldwide and is the major ground-based offensive and defensive force of the United States.

Mission:

The United States Army serves as the land-based branch of the U.S. Armed Forces. Section 3062 of Title 10, U.S. Code defines the purpose of the army as:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Army:

As the oldest and most senior branch of the U.S. military in order of precedence, the modern U.S. Army has its roots in the Continental Army, which was formed (14 June 1775) to fight the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)—before the United States of America was established as a country.

After the Revolutionary War, the Congress of the Confederation created the United States Army on 3 June 1784 to replace the disbanded Continental Army. The United States Army considers itself descended from the Continental Army, and dates its institutional inception from the origin of that armed force in 1775.

As a uniformed military service, the U.S. Army is part of the Department of the Army, which is one of the three military departments of the Department of Defense. The U.S. Army is headed by a civilian senior appointed civil servant, the Secretary of the Army (SECARMY) and by a chief military officer, the Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) who is also a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

It is the largest military branch, and in the fiscal year 2017, the projected end strength for the Regular Army (USA) was 476,000 soldiers; the Army National Guard (ARNG) had 343,000 soldiers and the United States Army Reserve (USAR) had 199,000 soldiers; the combined-component strength of the U.S. Army was 1,018,000 soldiers.[4]

As a branch of the armed forces, the mission of the U.S. Army is "to fight and win our Nation's wars, by providing prompt, sustained, land dominance, across the full range of military operations and the spectrum of conflict, in support of combatant commanders". The branch participates in conflicts worldwide and is the major ground-based offensive and defensive force of the United States.

Mission:

The United States Army serves as the land-based branch of the U.S. Armed Forces. Section 3062 of Title 10, U.S. Code defines the purpose of the army as:

- Preserving the peace and security and providing for the defense of the United States, the Commonwealths and possessions and any areas occupied by the United States

- Supporting the national policies

- Implementing the national objectives

- Overcoming any nations responsible for aggressive acts that imperil the peace and security of the United States

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Army:

- History

- Organization

- Personnel

- Equipment

- See also:

- Army.mil – United States Army official website

- Army.mil/photos – United States Army featured photos

- GoArmy.com – official recruiting site

- U.S. Army Collection – Missouri History Museum

- Finding Aids for researching the U.S. Army (compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History)

- America's Army (Video games for recruitment)

- Army CHESS (Computer Hardware Enterprise Software and Solutions)

- Army National Guard

- Comparative military ranks

- History of the United States Army

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of former United States Army medical units

- List of wars involving the United States

- Military–industrial complex

- Officer Candidate School (United States Army)

- Reserve Officers' Training Corps and Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps

- Soldier's Creed

- Structure of the United States Army

- Timeline of United States military operations

- Transformation of the United States Army

- U.S. Army Combat Arms Regimental System

- U.S. Army Regimental System

- United States Military Academy

- United States Army Basic Training

- United States Army Center of Military History

- United States Volunteers

- Vehicle markings of the United States military

- Warrant Officer Candidate School (United States Army)

United States Navy

YouTube Video: Watch a US Navy aircraft carrier launch all its F-18 fighter jets

YouTube Video: Life Aboard US Navy Ballistic Missile Submarine USS Wyoming

Pictured below:

TOP: The aircraft carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) of the US Navy on a mission

BOTTOM: US launches 'most advanced' stealth sub amid undersea rivalry

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most capable navy in the world, with the highest combined battle fleet tonnage and the world's largest aircraft carrier fleet, with eleven in service, and two new carriers under construction.

With 319,421 personnel on active duty and 99,616 in the Ready Reserve, the Navy is the third largest of the service branches. It has 282 deployable combat vessels and more than 3,700 operational aircraft as of March 2018. making it the second largest and second most powerful air force in the world.

The U.S. Navy traces its origins to the Continental Navy, which was established during the American Revolutionary War and was effectively disbanded as a separate entity shortly thereafter. The U.S. Navy played a major role in the American Civil War by blockading the Confederacy and seizing control of its rivers. It played the central role in the World War II defeat of Imperial Japan.

The 21st century U.S. Navy maintains a sizable global presence, deploying in strength in such areas as the Western Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean. It is a blue-water navy with the ability to project force onto the littoral regions of the world, engage in forward deployments during peacetime and rapidly respond to regional crises, making it a frequent actor in U.S. foreign and military policy.

The Navy is administratively managed by the Department of the Navy, which is headed by the civilian Secretary of the Navy. The Department of the Navy is itself a division of the Department of Defense, which is headed by the Secretary of Defense. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) is the most senior naval officer serving in the Department of the Navy.

Mission:

The mission of the Navy is to maintain, train and equip combat-ready Naval forces capable of winning wars, deterring aggression and maintaining freedom of the seas.

— Mission statement of the United States Navy.

The U.S. Navy is a seaborne branch of the military of the United States. The Navy's three primary areas of responsibility:

U.S. Navy training manuals state that the mission of the U.S. Armed Forces is "to be prepared to conduct prompt and sustained combat operations in support of the national interest. "As part of that establishment, the U.S. Navy's functions comprise sea control, power projection and nuclear deterrence, in addition to "sealift" duties

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Navy:

With 319,421 personnel on active duty and 99,616 in the Ready Reserve, the Navy is the third largest of the service branches. It has 282 deployable combat vessels and more than 3,700 operational aircraft as of March 2018. making it the second largest and second most powerful air force in the world.

The U.S. Navy traces its origins to the Continental Navy, which was established during the American Revolutionary War and was effectively disbanded as a separate entity shortly thereafter. The U.S. Navy played a major role in the American Civil War by blockading the Confederacy and seizing control of its rivers. It played the central role in the World War II defeat of Imperial Japan.

The 21st century U.S. Navy maintains a sizable global presence, deploying in strength in such areas as the Western Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean. It is a blue-water navy with the ability to project force onto the littoral regions of the world, engage in forward deployments during peacetime and rapidly respond to regional crises, making it a frequent actor in U.S. foreign and military policy.

The Navy is administratively managed by the Department of the Navy, which is headed by the civilian Secretary of the Navy. The Department of the Navy is itself a division of the Department of Defense, which is headed by the Secretary of Defense. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) is the most senior naval officer serving in the Department of the Navy.

Mission:

The mission of the Navy is to maintain, train and equip combat-ready Naval forces capable of winning wars, deterring aggression and maintaining freedom of the seas.

— Mission statement of the United States Navy.

The U.S. Navy is a seaborne branch of the military of the United States. The Navy's three primary areas of responsibility:

- The preparation of naval forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war.

- The maintenance of naval aviation, including land-based naval aviation, air transport essential for naval operations, and all air weapons and air techniques involved in the operations and activities of the Navy.

- The development of aircraft, weapons, tactics, technique, organization, and equipment of naval combat and service elements.

U.S. Navy training manuals state that the mission of the U.S. Armed Forces is "to be prepared to conduct prompt and sustained combat operations in support of the national interest. "As part of that establishment, the U.S. Navy's functions comprise sea control, power projection and nuclear deterrence, in addition to "sealift" duties

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Navy:

- History

- Organization

- Personnel

- Bases

- Equipment

- Naval jack

- Notable sailors

- See also:

- Official website

- "U.S. Naval Institute".

- A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower

- "Navy.com, USN official recruitment site".

- "U.S. Navy News website".

- "US Navy". GlobalSecurity.

- D'Alessandro, Michael P. (ed.). "Naval Open Source Intelligence".

- "United States Navy Official Website".

- Lanzendörfer, Tim. "The Pacific War: The U.S. Navy".

- "United States Navy Memorial".

- America's Naval Hardware – Life magazine slideshow

- "Photographic History of The U.S. Navy". Naval History. NavSource.

- "Haze Gray & Underway – Naval History and Photography". HazeGray.org.

- "U.S. Navy Ships". Military Analysis Network. Federation of America Scientists.

- U.S. Navy during the Cold War from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- "United States Navy in World War I". World War I at Sea.net. Retrieved 3 February 2007. (Includes warship losses.)

- "U.S. Navy in World War II". World War II on the World Wide Web. Hyper War. (Includes The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II.)

- "Our Fighting Ships". U.S. WW II Newsmap. Army Orientation Course. 29 June 1942. Hosted by the UNT Libraries Digital Collections

- "Strict Neutrality – Britain & France at War with Germany, September 1939 – May 1940". United States Navy and World War II. Naval-History.net.

- "The National Security Strategy of the United States of America".

- "Naval recognition-Grand Valley State University Archives and Special Collections".

- "US Navy SEALs Directory".

- United States Navy at the Wayback Machine (archived 4 January 1997)

- Ohio Replacement Submarine

- Spearhead-class expeditionary fast transport

- Bibliography of early American naval history

- Modern United States Navy carrier air operations

- Naval militia

- Women in the United States Navy

- United States Merchant Marine Academy

United States Marine Corps

YouTube Video: Marine Cpl. Carpenter awarded Medal of Honor

Pictured below: (L) Marines raising the Flag on Iwo Jima; (R) Two of the first female graduates of the School of Infantry-East's Infantry Training Battalion course, 2013

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is a branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations with (per the topics above) the United States Navy as well as the Army and Air Force.

The U.S. Marine Corps is one of the four armed service branches in the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States.

The Marine Corps has been a component of the U.S. Department of the Navy since 30 June 1834, working closely with naval forces.

The USMC operates installations on land and aboard sea-going amphibious warfare ships around the world. Additionally, several of the Marines' tactical aviation squadrons, primarily Marine Fighter Attack squadrons, are also embedded in Navy carrier air wings and operate from the aircraft carriers.

The history of the Marine Corps began when two battalions of Continental Marines were formed on 10 November 1775 in Philadelphia as a service branch of infantry troops capable of fighting both at sea and on shore.

In the Pacific theater of World War II the Corps took the lead in a massive campaign of amphibious warfare, advancing from island to island. As of 2017, the USMC has around 186,000 active duty members and some 38,500 reserve Marines. It is the smallest U.S. military service within the DoD.

Mission:

As outlined in 10 U.S.C. § 5063 and as originally introduced under the National Security Act of 1947, three primary areas of responsibility for the Marine Corps are:

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Marine Corp:

The U.S. Marine Corps is one of the four armed service branches in the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States.

The Marine Corps has been a component of the U.S. Department of the Navy since 30 June 1834, working closely with naval forces.

The USMC operates installations on land and aboard sea-going amphibious warfare ships around the world. Additionally, several of the Marines' tactical aviation squadrons, primarily Marine Fighter Attack squadrons, are also embedded in Navy carrier air wings and operate from the aircraft carriers.

The history of the Marine Corps began when two battalions of Continental Marines were formed on 10 November 1775 in Philadelphia as a service branch of infantry troops capable of fighting both at sea and on shore.

In the Pacific theater of World War II the Corps took the lead in a massive campaign of amphibious warfare, advancing from island to island. As of 2017, the USMC has around 186,000 active duty members and some 38,500 reserve Marines. It is the smallest U.S. military service within the DoD.

Mission:

As outlined in 10 U.S.C. § 5063 and as originally introduced under the National Security Act of 1947, three primary areas of responsibility for the Marine Corps are:

- Seizure or defense of advanced naval bases and other land operations to support naval campaigns;

- Development of tactics, technique, and equipment used by amphibious landing forces in coordination with the Army and Air Force; and

- Such other duties as the President or Department of Defense may direct.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Marine Corp:

- Mission

- History

- Organization

- Special Operations

- Personnel

- Uniforms

- Culture

- Equipment

- Relationship with other services

- Budget

- See also:

- United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve

- Marines.mil – Official site

- Official USMC recruitment site

- Marine Corps recruitment video

- Marine Corps History Division

- A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower

- Marine Corps Heritage Foundation

- Online Marine community

- Members of the USMC on RallyPoint

- An Unofficial Dictionary for Marines

United States Coast Guard

YouTube Video: Coast Guard Top 10 Rescue Videos

Pictured below: United States Coast Guard medevacs man south of Panama City, FL

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is a branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's seven uniformed services.

The Coast Guard is a maritime, military, multi-mission service unique among the U.S. military branches for having a maritime law enforcement mission (with jurisdiction in both domestic and international waters) and a federal regulatory agency mission as part of its mission set.

USCG operates under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security during peacetime, and can be transferred to the U.S. Department of the Navy by the U.S. President at any time, or by the U.S. Congress during times of war. This has happened twice, in 1917, during World War I, and in 1941, during World War II.

Created by Congress on 4 August 1790 at the request of Alexander Hamilton as the Revenue Marine, it is the oldest continuous seagoing service of the United States. As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton headed the Revenue Marine, whose original purpose was collecting customs duties in the nation's seaports.

By the 1860s, the service was known as the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service and the term Revenue Marine gradually fell into disuse.

The modern Coast Guard was formed by a merger of the Revenue Cutter Service and the U.S. Life-Saving Service on 28 January 1915, under the U.S. Department of the Treasury. As one of the country's five armed services, the Coast Guard has been involved in every U.S. war from 1790 to the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan.

The Coast Guard has 40,992 men and women on active duty, 7,000 reservists, 31,000 auxiliarists, and 8,577 full-time civilian employees, for a total workforce of 87,569.

The Coast Guard maintains an extensive fleet of 243 coastal and ocean-going patrol ships, tenders, tugs and icebreakers called "Cutters", and 1650 smaller boats, as well as an extensive aviation division consisting of 201 helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.

While the U.S. Coast Guard is the smallest of the U.S. military service branches, in terms of size, the U.S. Coast Guard by itself is the world's 12th largest naval force.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Coast Guard:

The Coast Guard is a maritime, military, multi-mission service unique among the U.S. military branches for having a maritime law enforcement mission (with jurisdiction in both domestic and international waters) and a federal regulatory agency mission as part of its mission set.

USCG operates under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security during peacetime, and can be transferred to the U.S. Department of the Navy by the U.S. President at any time, or by the U.S. Congress during times of war. This has happened twice, in 1917, during World War I, and in 1941, during World War II.

Created by Congress on 4 August 1790 at the request of Alexander Hamilton as the Revenue Marine, it is the oldest continuous seagoing service of the United States. As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton headed the Revenue Marine, whose original purpose was collecting customs duties in the nation's seaports.

By the 1860s, the service was known as the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service and the term Revenue Marine gradually fell into disuse.

The modern Coast Guard was formed by a merger of the Revenue Cutter Service and the U.S. Life-Saving Service on 28 January 1915, under the U.S. Department of the Treasury. As one of the country's five armed services, the Coast Guard has been involved in every U.S. war from 1790 to the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan.

The Coast Guard has 40,992 men and women on active duty, 7,000 reservists, 31,000 auxiliarists, and 8,577 full-time civilian employees, for a total workforce of 87,569.

The Coast Guard maintains an extensive fleet of 243 coastal and ocean-going patrol ships, tenders, tugs and icebreakers called "Cutters", and 1650 smaller boats, as well as an extensive aviation division consisting of 201 helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.

While the U.S. Coast Guard is the smallest of the U.S. military service branches, in terms of size, the U.S. Coast Guard by itself is the world's 12th largest naval force.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the United States Coast Guard:

- Mission

- A typical day

- History

- Organization

- Personnel

- Equipment

- Symbols

- Uniforms

- Coast Guard Reserve

- Women in the Coast Guard

- Coast Guard Auxiliary

- Deployable Operations Group

- Medals and honors

- Notable Coast Guardsmen

- Organizations

- In popular culture

- See also:

- U.S. Coast Guard Website

- Women & the U. S. Coast Guard

- Coast Guard in the Federal Register

- Reports on the Coast Guard, Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General

- 'A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower'

- U.S. Coast Guard Videos

- Coast Guard Personnel Locator

- All Comprehensive Security Plans for Mid and High Value Homes

- How to join the U.S. Coast Guard

- U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Website

- Coast Guard Channel

- Coast Guard News

- Greg Trauthwein (17 March 2014). "USCG ... Past, Present & Future". Maritime Reporter and Marine News magazines online. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- America's Waterway Watch at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2010-12-13)

- United States Coast Guard at the Wayback Machine (archived 29 January 1997)

- Coast Guard:

- AMVER

- Badges of the United States Coast Guard

- Chaplain of the Coast Guard

- Coast Guard Day

- Code of Federal Regulations, Title 33

- Joint Maritime Training Center

- List of United States Coast Guard cutters

- Maritime Law Enforcement Academy

- MARSEC

- National Data Buoy Center

- National Ice Center

- Naval militia

- North Pacific Coast Guard Agencies Forum

- Patrol Forces Southwest Asia

- SPARS

- U.S. Coast Guard Intelligence

- U.S. Coast Guard Legal Division

- United States Coast Guard Air Stations

- United States Coast Guard Police

- United States Coast Guard Research & Development Center

- United States Coast Guard Stations

- Women in the United States Coast Guard

- Related agencies:

Mutual Assured Destruction (Global Nuclear Policy), including the Doomsday Clock

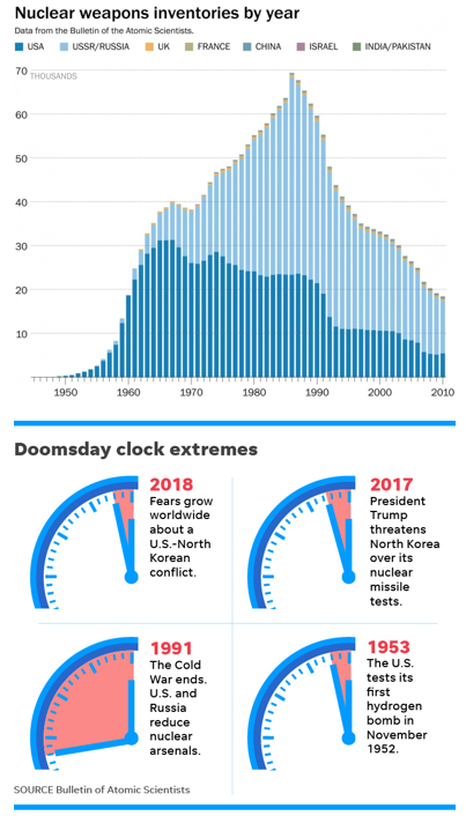

TOP: Donald Trump wants to ‘greatly’ expand U.S. nuclear capability. Here’s what that means. (Washington Post 12/22/2016)

BOTTOM: The Doomsday Clock just ticked closer to midnight (USA Today 1/25/2018)

- "YouTube Video: Nuclear 'Doomsday Clock' Is The Closest To Midnight It's Been Since The Cold War | TIME 1/28/2018

- YouTube Video: The insanity of nuclear deterrence Robert Green | TEDxChristchurch

- YouTube Video: Mutual assured destruction - Video Learning - WizScience.com

TOP: Donald Trump wants to ‘greatly’ expand U.S. nuclear capability. Here’s what that means. (Washington Post 12/22/2016)

BOTTOM: The Doomsday Clock just ticked closer to midnight (USA Today 1/25/2018)

Mutual assured destruction or mutually assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy in which a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by two or more opposing sides would cause the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender (see pre-emptive nuclear strike and second strike).

MAD is based on the theory of deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

Theory:

Under MAD, each side has enough nuclear weaponry to destroy the other side and that either side, if attacked for any reason by the other, would retaliate with equal or greater force. The expected result is an immediate, irreversible escalation of hostilities resulting in both combatants' mutual, total, and assured destruction.

The doctrine requires that neither side construct shelters on a massive scale. If one side constructed a similar system of shelters, it would violate the MAD doctrine and destabilize the situation, because it would have less to fear from a second strike. The same principle is invoked against missile defense.

The doctrine further assumes that neither side will dare to launch a first strike because the other side would launch on warning (also called fail-deadly) or with surviving forces (a second strike), resulting in unacceptable losses for both parties. The payoff of the MAD doctrine was and still is expected to be a tense but stable global peace.

The primary application of this doctrine started during the Cold War (1940s to 1991), in which MAD was seen as helping to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union while they engaged in smaller proxy wars around the world. It was also responsible for the arms race, as both nations struggled to keep nuclear parity, or at least retain second-strike capability. Although the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, the MAD doctrine continues to be applied.

Proponents of MAD as part of US and USSR strategic doctrine believed that nuclear war could best be prevented if neither side could expect to survive a full-scale nuclear exchange as a functioning state. Since the credibility of the threat is critical to such assurance, each side had to invest substantial capital in their nuclear arsenals even if they were not intended for use.

In addition, neither side could be expected or allowed to adequately defend itself against the other's nuclear missiles. This led both to the hardening and diversification of nuclear delivery systems (such as nuclear missile silos, ballistic missile submarines, and nuclear bombers kept at fail-safe points) and to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

This MAD scenario is often referred to as nuclear deterrence. The term "deterrence" is now used in this context; originally, its use was limited to legal terminology.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD):

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol which represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe. Maintained since 1947 by the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, The Clock is a metaphor for threats to humanity from unchecked scientific and technical advances. The Clock represents the hypothetical global catastrophe as "midnight" and the Bulletin's opinion on how close the world is to a global catastrophe as a number of "minutes" to midnight.

The factors influencing the Clock are nuclear risk and climate change. The Bulletin's Science and Security Board also monitors new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity.

The Clock's original setting in 1947 was seven minutes to midnight. It has been set backward and forward 23 times since then, the smallest-ever number of minutes to midnight being two (in 1953 and 2018) and the largest seventeen (in 1991).

The most recent officially announced setting—2 minutes to midnight—was made in January 2018, which was left unchanged in 2019 due to the twin threats of nuclear weapons and climate change, and the problem of those threats being "exacerbated this past year by the increased use of information warfare to undermine democracy around the world, amplifying risk from these and other threats and putting the future of civilization in extraordinary danger.”

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Doomsday Clock:

MAD is based on the theory of deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

Theory:

Under MAD, each side has enough nuclear weaponry to destroy the other side and that either side, if attacked for any reason by the other, would retaliate with equal or greater force. The expected result is an immediate, irreversible escalation of hostilities resulting in both combatants' mutual, total, and assured destruction.

The doctrine requires that neither side construct shelters on a massive scale. If one side constructed a similar system of shelters, it would violate the MAD doctrine and destabilize the situation, because it would have less to fear from a second strike. The same principle is invoked against missile defense.

The doctrine further assumes that neither side will dare to launch a first strike because the other side would launch on warning (also called fail-deadly) or with surviving forces (a second strike), resulting in unacceptable losses for both parties. The payoff of the MAD doctrine was and still is expected to be a tense but stable global peace.

The primary application of this doctrine started during the Cold War (1940s to 1991), in which MAD was seen as helping to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union while they engaged in smaller proxy wars around the world. It was also responsible for the arms race, as both nations struggled to keep nuclear parity, or at least retain second-strike capability. Although the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, the MAD doctrine continues to be applied.

Proponents of MAD as part of US and USSR strategic doctrine believed that nuclear war could best be prevented if neither side could expect to survive a full-scale nuclear exchange as a functioning state. Since the credibility of the threat is critical to such assurance, each side had to invest substantial capital in their nuclear arsenals even if they were not intended for use.

In addition, neither side could be expected or allowed to adequately defend itself against the other's nuclear missiles. This led both to the hardening and diversification of nuclear delivery systems (such as nuclear missile silos, ballistic missile submarines, and nuclear bombers kept at fail-safe points) and to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

This MAD scenario is often referred to as nuclear deterrence. The term "deterrence" is now used in this context; originally, its use was limited to legal terminology.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD):

- History

- Official policy

- Criticism

- See also

- Absolute war

- Appeasement

- Balance of terror

- Counterforce

- Moral equivalence

- Nuclear winter

- Nuclear missile defense

- Nuclear holocaust

- Nuclear peace

- Nuclear strategy

- Pyrrhic victory

- Rational choice theory

- Weapon of mass destruction

- "The Rise of U.S. Nuclear Primacy" from Foreign Affairs, March/April 2006

- First Strike and Mutual Deterrence from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Herman Kahn's Doomsday Machine

- Robert McNamara's "Mutual Deterrence" speech from 1967

- Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

- Nuclear Files.org Mutual Assured Destruction

- John G. Hines et al. Soviet Intentions 1965–1985. BDM, 1995.

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol which represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe. Maintained since 1947 by the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, The Clock is a metaphor for threats to humanity from unchecked scientific and technical advances. The Clock represents the hypothetical global catastrophe as "midnight" and the Bulletin's opinion on how close the world is to a global catastrophe as a number of "minutes" to midnight.

The factors influencing the Clock are nuclear risk and climate change. The Bulletin's Science and Security Board also monitors new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity.

The Clock's original setting in 1947 was seven minutes to midnight. It has been set backward and forward 23 times since then, the smallest-ever number of minutes to midnight being two (in 1953 and 2018) and the largest seventeen (in 1991).

The most recent officially announced setting—2 minutes to midnight—was made in January 2018, which was left unchanged in 2019 due to the twin threats of nuclear weapons and climate change, and the problem of those threats being "exacerbated this past year by the increased use of information warfare to undermine democracy around the world, amplifying risk from these and other threats and putting the future of civilization in extraordinary danger.”

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Doomsday Clock:

- History

- Reception

- In popular culture

- See also:

Artificial Intelligence Arms Race, including How A.I. Could Be Weaponized to Spread Disinformation

by New York Times

by New York Times

- YouTube Video: the Threat of A.I. Weapons

- YouTube Video: What happens when our computers get smarter than we are? by Nick Bostrom (TED.com)

- YouTube Video: Artificial Intelligence: it will kill us by Jay Tuck TEDxHamburgSalon

Click here for background about Artificial Intelligence

Click here to see New York Times OpEd: "How A.I. Could Be Weaponized to Spread Disinformation" By Cade Metz and Scott Blumenthal of the New York Times June 7, 2019

Artificial Arms Race:

An artificial intelligence arms race is a competition between two or more states to have its military forces equipped with the best "artificial intelligence" (AI). Since the mid-2010s, many analysts have argued that a such a global arms race for better artificial intelligence has already begun.

Stances toward military artificial intelligence:

Russia:

Russian General Viktor Bondarev, commander-in-chief of the Russian air force, has stated that as early as February 2017, Russia has been working on AI-guided missiles that can decide to switch targets mid-flight.

Reports by state-sponsored Russian media on potential military uses of AI increased in mid-2017. In May 2017, the CEO of Russia's Kronstadt Group, a defense contractor, stated that "there already exist completely autonomous AI operation systems that provide the means for UAV clusters, when they fulfill missions autonomously, sharing tasks between them, and interact", and that it is inevitable that "swarms of drones" will one day fly over combat zones.

Russia has been testing several autonomous and semi-autonomous combat systems, such as Kalashnikov's "neural net" combat module, with a machine gun, a camera, and an AI that its makers claim can make its own targeting judgements without human intervention.

In September 2017, during a National Knowledge Day address to over a million students in 16,000 Russian schools, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated "Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia but for all humankind... Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world".

The Russian government has strongly rejected any ban on lethal autonomous weapons systems, suggesting that such a ban could be ignored.

China:

Further information: Artificial intelligence industry in China

According to a February 2019 report by Gregory C. Allen of the Center for a New American Security, "China’s leadership – including President Xi Jinping – believes that being at the forefront in AI technology is critical to the future of global military and economic power competition."

Chinese military officials have said that their goal is to incorporate commercial AI technology to "narrow the gap between the Chinese military and global advanced powers."

The close ties between Silicon Valley and China, and the open nature of the American research community, has made the West's most advanced AI technology easily available to China; in addition, Chinese industry has numerous home-grown AI accomplishments of its own, such as Baidu passing a notable Chinese-language speech recognition capability benchmark in 2015. As of 2017, Beijing's roadmap aims to create a $150 billion AI industry by 2030.

Before 2013, Chinese defense procurement was mainly restricted to a few conglomerates; however, as of 2017, China often sources sensitive emerging technology such as drones and artificial intelligence from private start-up companies.

One Chinese state has pledged to invest $5 billion in AI. Beijing has committed $2 billion to an AI development park. The Japan Times reported in 2018 that annual private Chinese investment in AI is under $7 billion per year. AI startups in China received nearly half of total global investment in AI startups in 2017; the Chinese filed for nearly five times as many AI patents as did Americans.

China published a position paper in 2016 questioning the adequacy of existing international law to address the eventuality of fully autonomous weapons, becoming the first permanent member of the U.N. Security Council to broach the issue.

United States:

In 2014, former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel posited the "Third Offset Strategy" that rapid advances in artificial intelligence will define the next generation of warfare. According to data science and analytics firm Govini, The U.S. Department of Defense increased investment in artificial intelligence, big data and cloud computing from $5.6 billion in 2011 to $7.4 billion in 2016. However, the civilian NSF budget for AI saw no increase in 2017.

The U.S. has many military AI combat programs, such as the Sea Hunter autonomous warship, which is designed to operate for extended periods at sea without a single crew member, and to even guide itself in and out of port. As of 2017, a temporary US Department of Defense directive requires a human operator to be kept in the loop when it comes to the taking of human life by autonomous weapons systems. Japan Times reported in 2018 that the United States private investment is around $70 billion per year.

United Kingdom:

In 2015, the UK government opposed a ban on lethal autonomous weapons, stating that "international humanitarian law already provides sufficient regulation for this area", but that all weapons employed by UK armed forces would be "under human oversight and control".

Israel:

Israel's Harpy anti-radar "fire and forget" drone is designed to be launched by ground troops, and autonomously fly over an area to find and destroy radar that fits pre-determined criteria.

South Korea:

The South Korean Super aEgis II machine gun, unveiled in 2010, sees use both in South Korea and in the Middle East. It can identify, track, and destroy a moving target at a range of 4 km.

While the technology can theoretically operate without human intervention, in practice safeguards are installed to require manual input. A South Korean manufacturer states, "Our weapons don't sleep, like humans must. They can see in the dark, like humans can't. Our technology therefore plugs the gaps in human capability", and they want to "get to a place where our software can discern whether a target is friend, foe, civilian or military".

Trends:

According to Siemens, worldwide military spending on robotics was 5.1 billion USD in 2010 and 7.5 billion USD in 2015.

China became a top player in artificial intelligence research in the 2010s. According to the Financial Times, in 2016, for the first time, China published more AI papers than the entire European Union.

When restricted to number of AI papers in the top 5% of cited papers, China overtook the United States in 2016 but lagged behind the European Union. 23% of the researchers presenting at the 2017 American Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) conference were Chinese. Eric Schmidt, the former chairman of Alphabet, has predicted China will be the leading country in AI by 2025.

Proposals for international regulation:

As early as 2007, scholars such as AI professor Noel Sharkey have warned of "an emerging arms race among the hi-tech nations to develop autonomous submarines, fighter jets, battleships and tanks that can find their own targets and apply violent force without the involvement of meaningful human decisions".

As early as 2014, AI specialists such as Steve Omohundro have been warning that "An autonomous weapons arms race is already taking place". Miles Brundage of the University of Oxford has argued an AI arms race might be somewhat mitigated through diplomacy: "We saw in the various historical arms races that collaboration and dialog can pay dividends".

Over a hundred experts signed an open letter in 2017 calling on the UN to address the issue of lethal autonomous weapons; however, at a November 2017 session of the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), diplomats could not agree even on how to define such weapons.

The Indian ambassador and chair of the CCW stated that agreement on rules remained a distant prospect. As of 2017, twenty-two countries have called for a full ban on lethal autonomous weapons.

Many experts believe attempts to completely ban killer robots are likely to fail. A 2017 report from Harvard's Belfer Center predicts that AI has the potential to be as transformative as nuclear weapons.

The report further argues that "Preventing expanded military use of AI is likely impossible" and that "the more modest goal of safe and effective technology management must be pursued", such as banning the attaching of an AI dead man's switch to a nuclear arsenal. Part of the impracticality is that detecting treaty violations would be extremely difficult.

Other reactions to autonomous weapons:

A 2015 open letter calling for the ban of lethal automated weapons systems has been signed by tens of thousands of citizens, including scholars such as the following:

Professor Noel Sharkey of the University of Sheffield has warned that autonomous weapons will inevitably fall into the hands of terrorist groups such as the Islamic State.

Disassociation:

Many Western tech companies are leery of being associated too closely with the U.S. military, for fear of losing access to China's market. Furthermore, some researchers, such as DeepMind's Demis Hassabis, are ideologically opposed to contributing to military work.