Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Under this Page,

Our Community

we cover what everyone seeks: a sense of community and involvement wherever we live, whether a neighborhood, on a farm, or in a metropolitan city or suburb.

See Also:

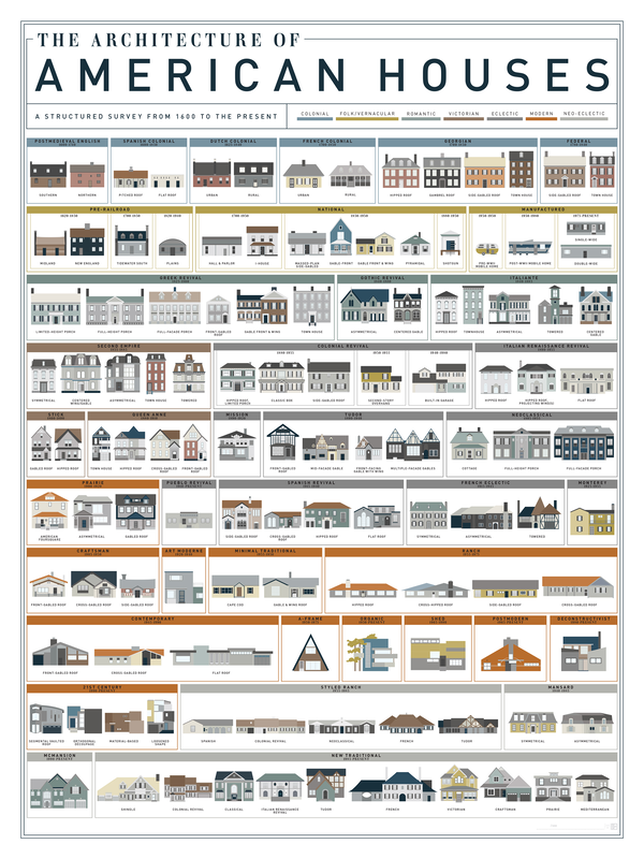

Architecture

Environment

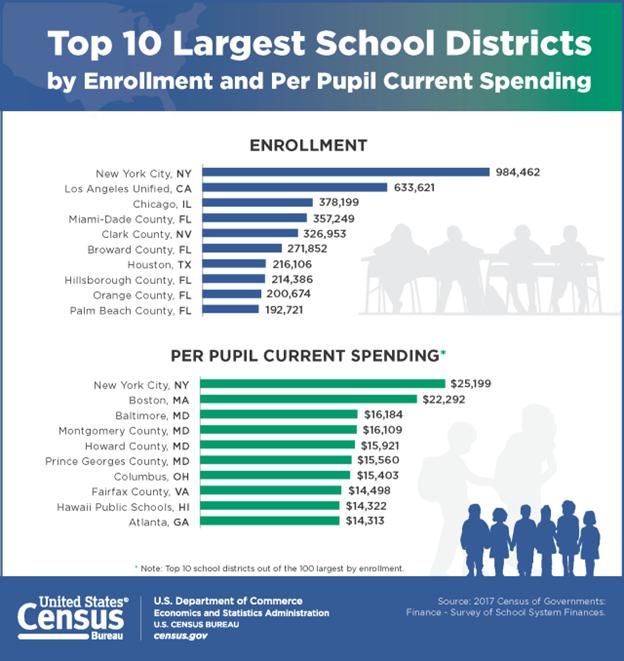

Education

Agriculture

Community

- YouTube Video: What makes a Good Community?

- YouTube Video: Types of Communities | Learn about communities for kids and help them learn how to identify them

- YouTube Video: How to Give Back to Our Communities | NowThis Kids

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, town, or neighborhood) or in virtual space through communication platforms.

Durable relations that extend beyond immediate genealogical ties also define a sense of community, important to their identity, practice, and roles in social institutions such as family, home, work, government, society, or humanity at large. Although communities are usually small relative to personal social ties, "community" may also refer to large group affiliations such as national communities, international communities, and virtual communities.

The English-language word "community" derives from the Old French comuneté (currently "Communauté"), which comes from the Latin communitas "community", "public spirit" (from Latin communis, "common").

Human communities may have intent, belief, resources, preferences, needs, and risks in common, affecting the identity of the participants and their degree of cohesiveness.

Perspectives of various disciplines:

Archaeology:

Archaeological studies of social communities use the term "community" in two ways, paralleling usage in other areas.

The first is an informal definition of community as a place where people used to live. In this sense it is synonymous with the concept of an ancient settlement - whether a hamlet, village, town, or city.

The second meaning resembles the usage of the term in other social sciences: a community is a group of people living near one another who interact socially.

Social interaction on a small scale can be difficult to identify with archaeological data. Most reconstructions of social communities by archaeologists rely on the principle that social interaction in the past was conditioned by physical distance. Therefore, a small village settlement likely constituted a social community and spatial subdivisions of cities and other large settlements may have formed communities.

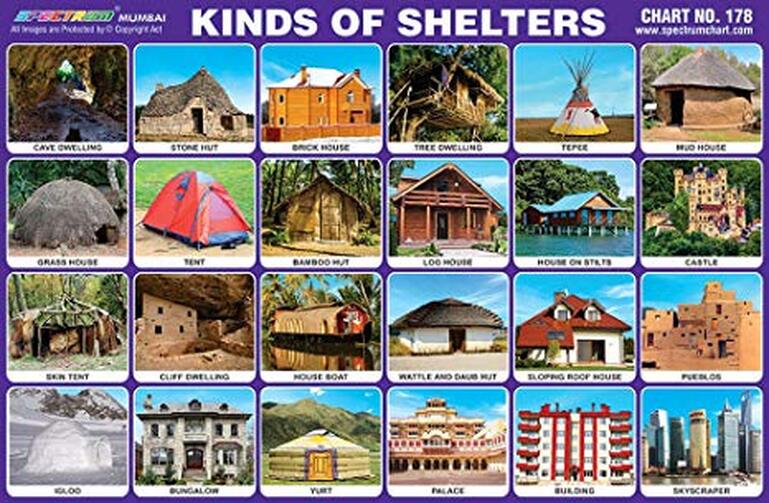

Archaeologists typically use similarities in material culture—from house types to styles of pottery—to reconstruct communities in the past. This classification method relies on the assumption that people or households will share more similarities in the types and styles of their material goods with other members of a social community than they will with outsiders.

Sociology:

Ecology:

Main article: Community (ecology)

In ecology, a community is an assemblage of populations - potentially of different species - interacting with one another. Community ecology is the branch of ecology that studies interactions between and among species. It considers how such interactions, along with interactions between species and the abiotic environment, affect social structure and species richness, diversity and patterns of abundance.

Species interact in three ways: competition, predation and mutualism:

The two main types of ecological communities are major communities, which are self-sustaining and self-regulating (such as a forest or a lake), and minor communities, which rely on other communities (like fungi decomposing a log) and are the building blocks of major communities.

Semantics:

The concept of "community" often has a positive semantic connotation, exploited rhetorically by populist politicians and by advertisers to promote feelings and associations of mutual well-being, happiness and togetherness - veering towards an almost-achievable utopian community, in fact.

In contrast, the epidemiological term "community transmission" can have negative implications; and instead of a "criminal community" one often speaks of a "criminal underworld" or of the "criminal fraternity".

Key concepts:

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft:

Main article: Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

In Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887), German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies described two types of human association: Gemeinschaft (usually translated as "community") and Gesellschaft ("society" or "association").

Tönnies proposed the Gemeinschaft–Gesellschaft dichotomy as a way to think about social ties. No group is exclusively one or the other. Gemeinschaft stress personal social interactions, and the roles, values, and beliefs based on such interactions. Gesellschaft stress indirect interactions, impersonal roles, formal values, and beliefs based on such interactions.

Sense of community:

Main article: Sense of community

In a seminal 1986 study, McMillan and Chavis identify four elements of "sense of community":

A "sense of community index (SCI) was developed by Chavis and colleagues, and revised and adapted by others. Although originally designed to assess sense of community in neighborhoods, the index has been adapted for use in schools, the workplace, and a variety of types of communities.

Studies conducted by the APPA indicate that young adults who feel a sense of belonging in a community, particularly small communities, develop fewer psychiatric and depressive disorders than those who do not have the feeling of love and belonging.

Socialization:

Main article: Socialization

The process of learning to adopt the behavior patterns of the community is called socialization. The most fertile time of socialization is usually the early stages of life, during which individuals develop the skills and knowledge and learn the roles necessary to function within their culture and social environment.

For some psychologists, especially those in the psychodynamic tradition, the most important period of socialization is between the ages of one and ten. But socialization also includes adults moving into a significantly different environment where they must learn a new set of behaviors.

Socialization is influenced primarily by the family, through which children first learn community norms. Other important influences include schools, peer groups, people, mass media, the workplace, and government. The degree to which the norms of a particular society or community are adopted determines one's willingness to engage with others. The norms of tolerance, reciprocity, and trust are important "habits of the heart," as de Tocqueville put it, in an individual's involvement in community.

Community development:

Main article: Community development

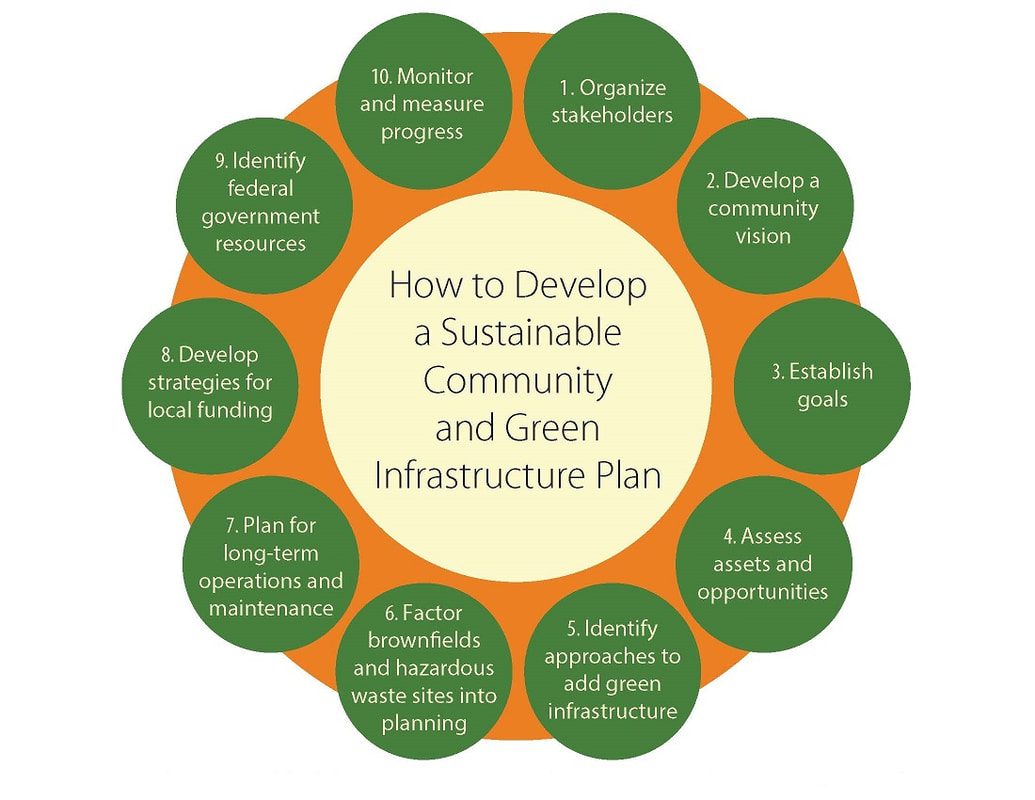

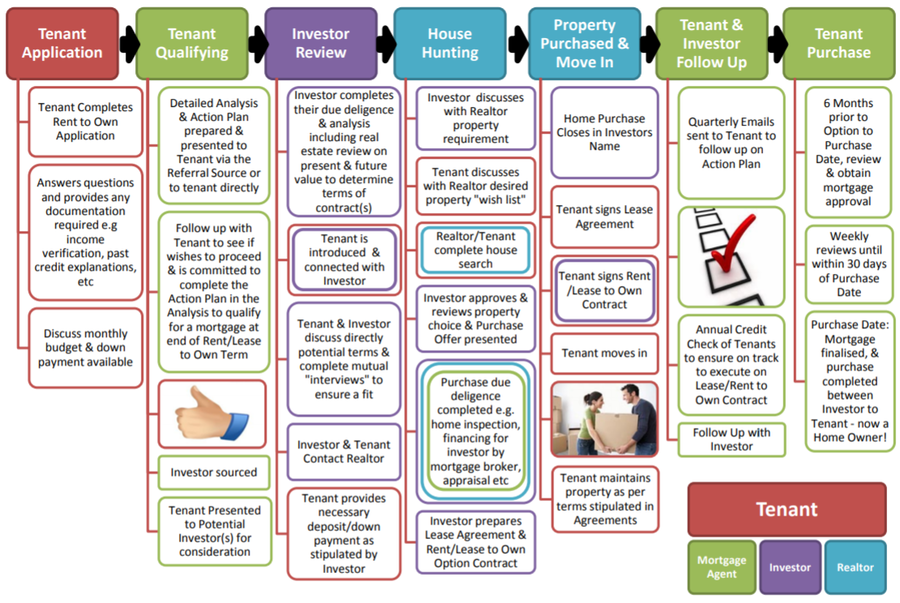

Community development is often linked with community work or community planning, and may involve stakeholders, foundations, governments, or contracted entities including non-government organizations (NGOs), universities or government agencies to progress the social well-being of local, regional and, sometimes, national communities.

More grassroots efforts, called community building or community organizing, seek to empower individuals and groups of people by providing them with the skills they need to effect change in their own communities. These skills often assist in building political power through the formation of large social groups working for a common agenda.

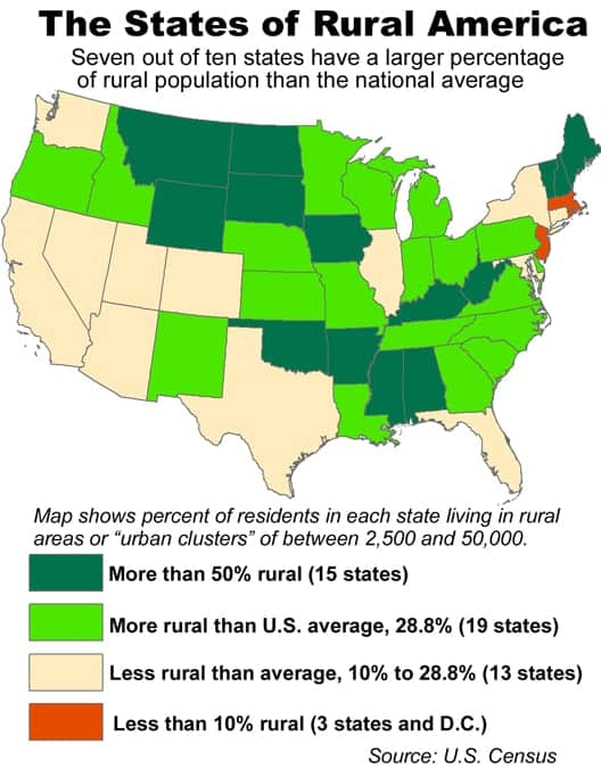

Community development practitioners must understand both how to work with individuals and how to affect communities' positions within the context of larger social institutions. Public administrators, in contrast, need to understand community development in the context of rural and urban development, housing and economic development, and community, organizational and business development.

Formal accredited programs conducted by universities, as part of degree granting institutions, are often used to build a knowledge base to drive curricula in public administration, sociology and community studies. The General Social Survey from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago and the Saguaro Seminar at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University are examples of national community development in the United States.

The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University in New York State offers core courses in community and economic development, and in areas ranging from non-profit development to US budgeting (federal to local, community funds).

In the United Kingdom, the University of Oxford has led in providing extensive research in the field through its Community Development Journal, used worldwide by sociologists and community development practitioners.

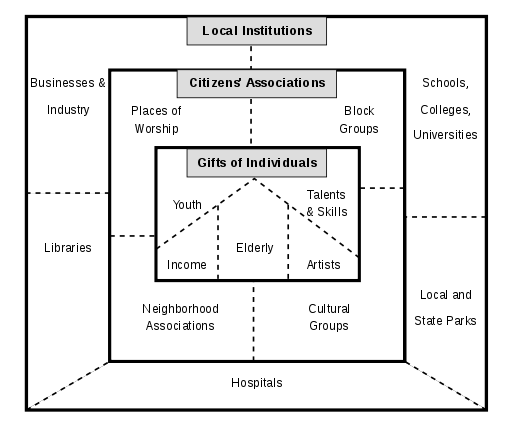

At the intersection between community development and community building are a number of programs and organizations with community development tools. One example of this is the program of the Asset Based Community Development Institute of Northwestern University.

The institute makes available downloadable tools to assess community assets and make connections between non-profit groups and other organizations that can help in community building. The Institute focuses on helping communities develop by "mobilizing neighborhood assets" – building from the inside out rather than the outside in. In the disability field, community building was prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s with roots in John McKnight's approaches.

Community building and organizing:

In The Different Drum: Community-Making and Peace (1987) Scott Peck argues that the almost accidental sense of community that exists at times of crisis can be consciously built. Peck believes that conscious community building is a process of deliberate design based on the knowledge and application of certain rules. He states that this process goes through four stages:

In 1991, Peck remarked that building a sense of community is easy but maintaining this sense of community is difficult in the modern world.

The three basic types of community organizing are grassroots organizing, coalition building, and "institution-based community organizing," (also called "broad-based community organizing," an example of which is faith-based community organizing, or Congregation-based Community Organizing).

Community building can use a wide variety of practices, ranging from simple events (e.g., potlucks, small book clubs) to larger-scale efforts (e.g., mass festivals, construction projects that involve local participants rather than outside contractors).

Community building that is geared toward citizen action is usually termed "community organizing." In these cases, organized community groups seek accountability from elected officials and increased direct representation within decision-making bodies. Where good-faith negotiations fail, these constituency-led organizations seek to pressure the decision-makers through a variety of means, including picketing, boycotting, sit-ins, petitioning, and electoral politics.

Community organizing can focus on more than just resolving specific issues. Organizing often means building a widely accessible power structure, often with the end goal of distributing power equally throughout the community. Community organizers generally seek to build groups that are open and democratic in governance. Such groups facilitate and encourage consensus decision-making with a focus on the general health of the community rather than a specific interest group.

If communities are developed based on something they share in common, whether location or values, then one challenge for developing communities is how to incorporate individuality and differences. Rebekah Nathan suggests in her book, My Freshman Year, we are drawn to developing communities totally based on sameness, despite stated commitments to diversity, such as those found on university websites.

Types of community:

A number of ways to categorize types of community have been proposed. One such breakdown is as follows:

The usual categorizations of community relations have a number of problems:

(1) they tend to give the impression that a particular community can be defined as just this kind or another;

(2) they tend to conflate modern and customary community relations;

(3) they tend to take sociological categories such as ethnicity or race as given, forgetting that different ethnically defined persons live in different kinds of communities —grounded, interest-based, diasporic, etc.

In response to these problems, Paul James and his colleagues have developed a taxonomy that maps community relations, and recognizes that actual communities can be characterized by different kinds of relations at the same time:

In these terms, communities can be nested and/or intersecting; one community can contain another—for example a location-based community may contain a number of ethnic communities. Both lists above can used in a cross-cutting matrix in relation to each other.

Internet communities:

In general, virtual communities value knowledge and information as currency or social resource. What differentiates virtual communities from their physical counterparts is the extent and impact of "weak ties", which are the relationships acquaintances or strangers form to acquire information through online networks.

Relationships among members in a virtual community tend to focus on information exchange about specific topics. A survey conducted by Pew Internet and The American Life Project in 2001 found those involved in entertainment, professional, and sports virtual-groups focused their activities on obtaining information.

An epidemic of bullying and harassment has arisen from the exchange of information between strangers, especially among teenagers, in virtual communities. Despite attempts to implement anti-bullying policies, Sheri Bauman, professor of counselling at the University of Arizona, claims the "most effective strategies to prevent bullying" may cost companies revenue.

Virtual Internet-mediated communities can interact with offline real-life activity, potentially forming strong and tight-knit groups such as QAnon.

See also:

Durable relations that extend beyond immediate genealogical ties also define a sense of community, important to their identity, practice, and roles in social institutions such as family, home, work, government, society, or humanity at large. Although communities are usually small relative to personal social ties, "community" may also refer to large group affiliations such as national communities, international communities, and virtual communities.

The English-language word "community" derives from the Old French comuneté (currently "Communauté"), which comes from the Latin communitas "community", "public spirit" (from Latin communis, "common").

Human communities may have intent, belief, resources, preferences, needs, and risks in common, affecting the identity of the participants and their degree of cohesiveness.

Perspectives of various disciplines:

Archaeology:

Archaeological studies of social communities use the term "community" in two ways, paralleling usage in other areas.

The first is an informal definition of community as a place where people used to live. In this sense it is synonymous with the concept of an ancient settlement - whether a hamlet, village, town, or city.

The second meaning resembles the usage of the term in other social sciences: a community is a group of people living near one another who interact socially.

Social interaction on a small scale can be difficult to identify with archaeological data. Most reconstructions of social communities by archaeologists rely on the principle that social interaction in the past was conditioned by physical distance. Therefore, a small village settlement likely constituted a social community and spatial subdivisions of cities and other large settlements may have formed communities.

Archaeologists typically use similarities in material culture—from house types to styles of pottery—to reconstruct communities in the past. This classification method relies on the assumption that people or households will share more similarities in the types and styles of their material goods with other members of a social community than they will with outsiders.

Sociology:

Ecology:

Main article: Community (ecology)

In ecology, a community is an assemblage of populations - potentially of different species - interacting with one another. Community ecology is the branch of ecology that studies interactions between and among species. It considers how such interactions, along with interactions between species and the abiotic environment, affect social structure and species richness, diversity and patterns of abundance.

Species interact in three ways: competition, predation and mutualism:

- Competition typically results in a double negative—that is both species lose in the interaction.

- Predation involves a win/lose situation, with one species winning.

- Mutualism sees both species co-operating in some way, with both winning.

The two main types of ecological communities are major communities, which are self-sustaining and self-regulating (such as a forest or a lake), and minor communities, which rely on other communities (like fungi decomposing a log) and are the building blocks of major communities.

Semantics:

The concept of "community" often has a positive semantic connotation, exploited rhetorically by populist politicians and by advertisers to promote feelings and associations of mutual well-being, happiness and togetherness - veering towards an almost-achievable utopian community, in fact.

In contrast, the epidemiological term "community transmission" can have negative implications; and instead of a "criminal community" one often speaks of a "criminal underworld" or of the "criminal fraternity".

Key concepts:

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft:

Main article: Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

In Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887), German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies described two types of human association: Gemeinschaft (usually translated as "community") and Gesellschaft ("society" or "association").

Tönnies proposed the Gemeinschaft–Gesellschaft dichotomy as a way to think about social ties. No group is exclusively one or the other. Gemeinschaft stress personal social interactions, and the roles, values, and beliefs based on such interactions. Gesellschaft stress indirect interactions, impersonal roles, formal values, and beliefs based on such interactions.

Sense of community:

Main article: Sense of community

In a seminal 1986 study, McMillan and Chavis identify four elements of "sense of community":

- membership: feeling of belonging or of sharing a sense of personal relatedness,

- influence: mattering, making a difference to a group and of the group mattering to its members

- reinforcement: integration and fulfillment of needs,

- shared emotional connection.

A "sense of community index (SCI) was developed by Chavis and colleagues, and revised and adapted by others. Although originally designed to assess sense of community in neighborhoods, the index has been adapted for use in schools, the workplace, and a variety of types of communities.

Studies conducted by the APPA indicate that young adults who feel a sense of belonging in a community, particularly small communities, develop fewer psychiatric and depressive disorders than those who do not have the feeling of love and belonging.

Socialization:

Main article: Socialization

The process of learning to adopt the behavior patterns of the community is called socialization. The most fertile time of socialization is usually the early stages of life, during which individuals develop the skills and knowledge and learn the roles necessary to function within their culture and social environment.

For some psychologists, especially those in the psychodynamic tradition, the most important period of socialization is between the ages of one and ten. But socialization also includes adults moving into a significantly different environment where they must learn a new set of behaviors.

Socialization is influenced primarily by the family, through which children first learn community norms. Other important influences include schools, peer groups, people, mass media, the workplace, and government. The degree to which the norms of a particular society or community are adopted determines one's willingness to engage with others. The norms of tolerance, reciprocity, and trust are important "habits of the heart," as de Tocqueville put it, in an individual's involvement in community.

Community development:

Main article: Community development

Community development is often linked with community work or community planning, and may involve stakeholders, foundations, governments, or contracted entities including non-government organizations (NGOs), universities or government agencies to progress the social well-being of local, regional and, sometimes, national communities.

More grassroots efforts, called community building or community organizing, seek to empower individuals and groups of people by providing them with the skills they need to effect change in their own communities. These skills often assist in building political power through the formation of large social groups working for a common agenda.

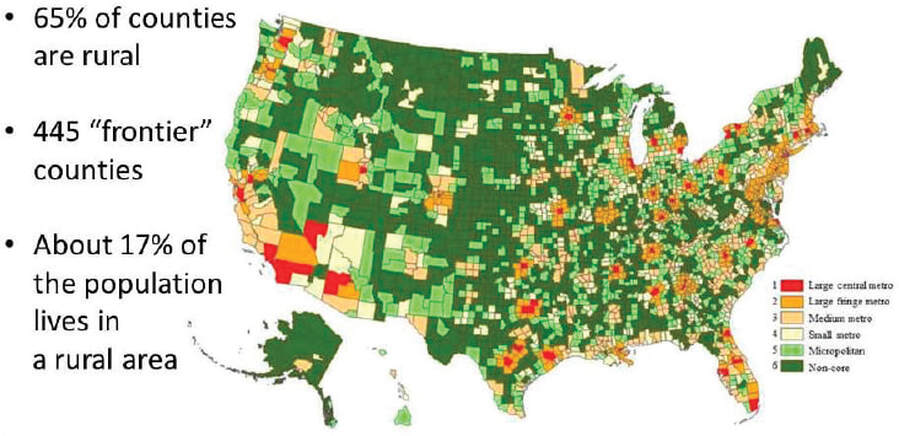

Community development practitioners must understand both how to work with individuals and how to affect communities' positions within the context of larger social institutions. Public administrators, in contrast, need to understand community development in the context of rural and urban development, housing and economic development, and community, organizational and business development.

Formal accredited programs conducted by universities, as part of degree granting institutions, are often used to build a knowledge base to drive curricula in public administration, sociology and community studies. The General Social Survey from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago and the Saguaro Seminar at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University are examples of national community development in the United States.

The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University in New York State offers core courses in community and economic development, and in areas ranging from non-profit development to US budgeting (federal to local, community funds).

In the United Kingdom, the University of Oxford has led in providing extensive research in the field through its Community Development Journal, used worldwide by sociologists and community development practitioners.

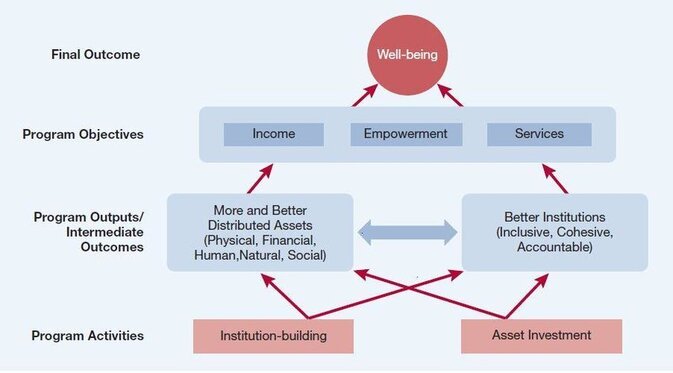

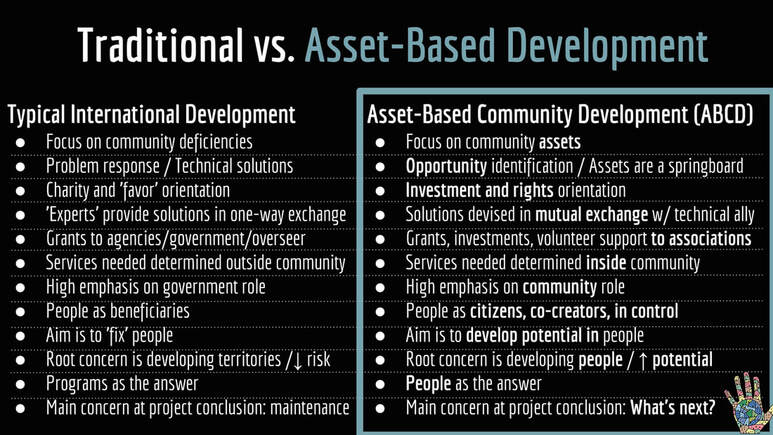

At the intersection between community development and community building are a number of programs and organizations with community development tools. One example of this is the program of the Asset Based Community Development Institute of Northwestern University.

The institute makes available downloadable tools to assess community assets and make connections between non-profit groups and other organizations that can help in community building. The Institute focuses on helping communities develop by "mobilizing neighborhood assets" – building from the inside out rather than the outside in. In the disability field, community building was prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s with roots in John McKnight's approaches.

Community building and organizing:

In The Different Drum: Community-Making and Peace (1987) Scott Peck argues that the almost accidental sense of community that exists at times of crisis can be consciously built. Peck believes that conscious community building is a process of deliberate design based on the knowledge and application of certain rules. He states that this process goes through four stages:

- Pseudocommunity: When people first come together, they try to be "nice" and present what they feel are their most personable and friendly characteristics.

- Chaos: People move beyond the inauthenticity of pseudo-community and feel safe enough to present their "shadow" selves.

- Emptiness: Moves beyond the attempts to fix, heal and convert of the chaos stage, when all people become capable of acknowledging their own woundedness and brokenness, common to human beings.

- True community: Deep respect and true listening for the needs of the other people in this community.

In 1991, Peck remarked that building a sense of community is easy but maintaining this sense of community is difficult in the modern world.

The three basic types of community organizing are grassroots organizing, coalition building, and "institution-based community organizing," (also called "broad-based community organizing," an example of which is faith-based community organizing, or Congregation-based Community Organizing).

Community building can use a wide variety of practices, ranging from simple events (e.g., potlucks, small book clubs) to larger-scale efforts (e.g., mass festivals, construction projects that involve local participants rather than outside contractors).

Community building that is geared toward citizen action is usually termed "community organizing." In these cases, organized community groups seek accountability from elected officials and increased direct representation within decision-making bodies. Where good-faith negotiations fail, these constituency-led organizations seek to pressure the decision-makers through a variety of means, including picketing, boycotting, sit-ins, petitioning, and electoral politics.

Community organizing can focus on more than just resolving specific issues. Organizing often means building a widely accessible power structure, often with the end goal of distributing power equally throughout the community. Community organizers generally seek to build groups that are open and democratic in governance. Such groups facilitate and encourage consensus decision-making with a focus on the general health of the community rather than a specific interest group.

If communities are developed based on something they share in common, whether location or values, then one challenge for developing communities is how to incorporate individuality and differences. Rebekah Nathan suggests in her book, My Freshman Year, we are drawn to developing communities totally based on sameness, despite stated commitments to diversity, such as those found on university websites.

Types of community:

A number of ways to categorize types of community have been proposed. One such breakdown is as follows:

- Location-based Communities: range from the local neighborhood, suburb, village, town or city, region, nation or even the planet as a whole. These are also called communities of place.

- Identity-based Communities: range from the local clique, sub-culture, ethnic group, religious, multicultural or pluralistic civilization, or the global community cultures of today. They may be included as communities of need or identity, such as disabled persons, or frail aged people.

- Organizationally-based Communities: range from communities organized informally around family or network-based guilds and associations to more formal incorporated associations, political decision making structures, economic enterprises, or professional associations at a small, national or international scale.

The usual categorizations of community relations have a number of problems:

(1) they tend to give the impression that a particular community can be defined as just this kind or another;

(2) they tend to conflate modern and customary community relations;

(3) they tend to take sociological categories such as ethnicity or race as given, forgetting that different ethnically defined persons live in different kinds of communities —grounded, interest-based, diasporic, etc.

In response to these problems, Paul James and his colleagues have developed a taxonomy that maps community relations, and recognizes that actual communities can be characterized by different kinds of relations at the same time:

- Grounded community relations. This involves enduring attachment to particular places and particular people. It is the dominant form taken by customary and tribal communities. In these kinds of communities, the land is fundamental to identity.

- Life-style community relations. This involves giving primacy to communities coming together around particular chosen ways of life, such as morally charged or interest-based relations or just living or working in the same location. Hence the following sub-forms:

- community-life as morally bounded, a form taken by many traditional faith-based communities.

- community-life as proximately-related, where neighborhood or commonality of association forms a community of convenience, or a community of place (see below).

- community-life as interest-based, including sporting, leisure-based and business communities which come together for regular moments of engagement.

- Projected community relations. This is where a community is self-consciously treated as an entity to be projected and re-created. It can be projected as through thin advertising slogan, for example gated community, or can take the form of ongoing associations of people who seek political integration, communities of practice based on professional projects, associative communities which seek to enhance and support individual creativity, autonomy and mutuality. A nation is one of the largest forms of projected or imagined community.

In these terms, communities can be nested and/or intersecting; one community can contain another—for example a location-based community may contain a number of ethnic communities. Both lists above can used in a cross-cutting matrix in relation to each other.

Internet communities:

In general, virtual communities value knowledge and information as currency or social resource. What differentiates virtual communities from their physical counterparts is the extent and impact of "weak ties", which are the relationships acquaintances or strangers form to acquire information through online networks.

Relationships among members in a virtual community tend to focus on information exchange about specific topics. A survey conducted by Pew Internet and The American Life Project in 2001 found those involved in entertainment, professional, and sports virtual-groups focused their activities on obtaining information.

An epidemic of bullying and harassment has arisen from the exchange of information between strangers, especially among teenagers, in virtual communities. Despite attempts to implement anti-bullying policies, Sheri Bauman, professor of counselling at the University of Arizona, claims the "most effective strategies to prevent bullying" may cost companies revenue.

Virtual Internet-mediated communities can interact with offline real-life activity, potentially forming strong and tight-knit groups such as QAnon.

See also:

Sense of Community

- YouTube Video: Ten Ways to Build a Sense of Community

- YouTube Video: I Am Because You Are - Building a Sense of Community | Dr. Patrice McClellan | TEDxWayPublicLibrary

- YouTube Video: What Does Community Mean To You?

Sense of community (or psychological sense of community) is a concept in community psychology, social psychology, and community social work, as well as in several other research disciplines, such as urban sociology, which focuses on the experience of community rather than its structure, formation, setting, or other features. The latter is the province of public administration or community services administration which needs to understand how structures influence this feeling and psychological sense of community.

Sociologists, social psychologists, anthropologists, and others have theorized about and carried out empirical research on community, but the psychological approach asks questions about the individual's perception, understanding, attitudes, feelings, etc. about community and his or her relationship to it and to others' participation—indeed to the complete, multifaceted community experience.

In his seminal 1974 book, psychologist Seymour B. Sarason proposed that psychological sense of community become the conceptual center for the psychology of community, asserting that it "is one of the major bases for self-definition." By 1986 it was regarded as a central overarching concept for community psychology (Sarason, 1986; Chavis & Pretty, 1999).In addition, the theoretical concept entered the other applied academic disciplines as part of "communities for all" initiatives in the US.

Among theories of sense of community proposed by psychologists, McMillan & Chavis's (1986) is by far the most influential, and is the starting point for most of the recent research in the field. It is discussed in detail below.

Definitions:

For Sarason, psychological sense of community is "the perception of similarity to others, an acknowledged interdependence with others, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by giving to or doing for others what one expects from them, and the feeling that one is part of a larger dependable and stable structure" (1974, p. 157).

McMillan & Chavis (1986) define a sense of community as "a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together."

Gusfield (1975) identified two dimensions of community: territorial and relational. The relational dimension of community has to do with the nature and quality of relationships in that community, and some communities may even have no discernible territorial demarcation, as in the case of a community of scholars working in a particular specialty, who have some kind of contact and quality of relationship, but may live and work in disparate locations, perhaps even throughout the world.

Other communities may seem to be defined primarily according to territory, as in the case of neighbourhoods, but even in such cases, proximity or shared territory cannot by itself constitute a community; the relational dimension is also essential.

Factor analysis of their urban neighbourhoods questionnaire yielded two distinct factors that Riger and Lavrakas (1981) characterized as "social bonding" and "physical rootedness", very similar to the two dimensions proposed by Gusfield.

Early work on psychological sense of community was based on neighborhoods as the referent, and found a relationship between psychological sense of community and greater participation (Hunter, 1975; Wandersman & Giamartino, 1980)

These initial studies lacked a clearly articulated conceptual framework, however, and none of the measures developed were based on a theoretical definition of psychological sense of community.

Primary theoretical foundation: McMillan and Chavis:

McMillan & Chavis's (1986) theory (and instrument) are the most broadly validated and widely utilized in this area in the psychological literature. They prefer the abbreviated label "sense of community", and propose that sense of community is composed of four elements.

Four elements of sense of community:

There are four elements of "sense of community" according to the McMillan & Chavis theory:

1) Membership: Membership includes five attributes:

2) Influence: Influence works both ways: members need to feel that they have some influence in the group, and some influence by the group on its members is needed for group cohesion. Current researches (e.g. Chigbu, 2013) on rural and urban communities have found that sense of community is a major factor.

3) Integration and fulfillment of needs: Members feel rewarded in some way for their participation in the community.

4) Shared emotional connection: The "definitive element for true community" (1986, p. 14), it includes shared history and shared participation (or at least identification with the history).

Dynamics within and between the elements:

McMillan & Chavis (1986) give the following example to illustrate the dynamics within and between these four elements (p. 16): Someone puts an announcement on the dormitory bulletin board about the formation of an intramural dormitory basketball team. People attend the organizational meeting as strangers out of their individual needs (integration and fulfillment of needs).

The team is bound by place of residence (membership boundaries are set) and spends time together in practice (the contact hypothesis). They play a game and win (successful shared valent event). While playing, members exert energy on behalf of the team (personal investment in the group).

As the team continues to win, team members become recognized and congratulated (gaining honor and status for being members). Someone suggests that they all buy matching shirts and shoes (common symbols) and they do so (influence).

Current research:

In their 2002 study of a community of interest, specifically the science fiction fandom community, Obst, Zinkiewicz, and Smith suggest Conscious Identification as the fifth dimension (Obst, 2002).

Empirical assessment:

Chavis et al.'s Sense of Community Index (SCI) (see Chipuer & Pretty, 1999; Long & Perkins, 2003), originally designed primarily in reference to neighborhoods, can be adapted to study other communities as well, including the workplace, schools, religious communities, communities of interest, etc.

See also:

Sociologists, social psychologists, anthropologists, and others have theorized about and carried out empirical research on community, but the psychological approach asks questions about the individual's perception, understanding, attitudes, feelings, etc. about community and his or her relationship to it and to others' participation—indeed to the complete, multifaceted community experience.

In his seminal 1974 book, psychologist Seymour B. Sarason proposed that psychological sense of community become the conceptual center for the psychology of community, asserting that it "is one of the major bases for self-definition." By 1986 it was regarded as a central overarching concept for community psychology (Sarason, 1986; Chavis & Pretty, 1999).In addition, the theoretical concept entered the other applied academic disciplines as part of "communities for all" initiatives in the US.

Among theories of sense of community proposed by psychologists, McMillan & Chavis's (1986) is by far the most influential, and is the starting point for most of the recent research in the field. It is discussed in detail below.

Definitions:

For Sarason, psychological sense of community is "the perception of similarity to others, an acknowledged interdependence with others, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by giving to or doing for others what one expects from them, and the feeling that one is part of a larger dependable and stable structure" (1974, p. 157).

McMillan & Chavis (1986) define a sense of community as "a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together."

Gusfield (1975) identified two dimensions of community: territorial and relational. The relational dimension of community has to do with the nature and quality of relationships in that community, and some communities may even have no discernible territorial demarcation, as in the case of a community of scholars working in a particular specialty, who have some kind of contact and quality of relationship, but may live and work in disparate locations, perhaps even throughout the world.

Other communities may seem to be defined primarily according to territory, as in the case of neighbourhoods, but even in such cases, proximity or shared territory cannot by itself constitute a community; the relational dimension is also essential.

Factor analysis of their urban neighbourhoods questionnaire yielded two distinct factors that Riger and Lavrakas (1981) characterized as "social bonding" and "physical rootedness", very similar to the two dimensions proposed by Gusfield.

Early work on psychological sense of community was based on neighborhoods as the referent, and found a relationship between psychological sense of community and greater participation (Hunter, 1975; Wandersman & Giamartino, 1980)

- perceived safety (Doolittle & McDonald, 1978),

- ability to function competently in the community (Glynn, 1981),

- social bonding (Riger & Lavrakas, 1981),

- social fabric (strengths of interpersonal relationship) (Ahlbrandt & Cunningham, 1979),

- greater sense of purpose and perceived control (Bachrach & Zautra, 1985),

- and greater civic contributions (charitable contributions and civic involvement) (Davidson & Cotter, 1986).

These initial studies lacked a clearly articulated conceptual framework, however, and none of the measures developed were based on a theoretical definition of psychological sense of community.

Primary theoretical foundation: McMillan and Chavis:

McMillan & Chavis's (1986) theory (and instrument) are the most broadly validated and widely utilized in this area in the psychological literature. They prefer the abbreviated label "sense of community", and propose that sense of community is composed of four elements.

Four elements of sense of community:

There are four elements of "sense of community" according to the McMillan & Chavis theory:

1) Membership: Membership includes five attributes:

- boundaries

- emotional safety

- a sense of belonging and identification

- personal investment

- a common symbol system

2) Influence: Influence works both ways: members need to feel that they have some influence in the group, and some influence by the group on its members is needed for group cohesion. Current researches (e.g. Chigbu, 2013) on rural and urban communities have found that sense of community is a major factor.

3) Integration and fulfillment of needs: Members feel rewarded in some way for their participation in the community.

4) Shared emotional connection: The "definitive element for true community" (1986, p. 14), it includes shared history and shared participation (or at least identification with the history).

Dynamics within and between the elements:

McMillan & Chavis (1986) give the following example to illustrate the dynamics within and between these four elements (p. 16): Someone puts an announcement on the dormitory bulletin board about the formation of an intramural dormitory basketball team. People attend the organizational meeting as strangers out of their individual needs (integration and fulfillment of needs).

The team is bound by place of residence (membership boundaries are set) and spends time together in practice (the contact hypothesis). They play a game and win (successful shared valent event). While playing, members exert energy on behalf of the team (personal investment in the group).

As the team continues to win, team members become recognized and congratulated (gaining honor and status for being members). Someone suggests that they all buy matching shirts and shoes (common symbols) and they do so (influence).

Current research:

In their 2002 study of a community of interest, specifically the science fiction fandom community, Obst, Zinkiewicz, and Smith suggest Conscious Identification as the fifth dimension (Obst, 2002).

Empirical assessment:

Chavis et al.'s Sense of Community Index (SCI) (see Chipuer & Pretty, 1999; Long & Perkins, 2003), originally designed primarily in reference to neighborhoods, can be adapted to study other communities as well, including the workplace, schools, religious communities, communities of interest, etc.

See also:

- Anomie, (The Division of Labor in Society, Émile Durkheim)

- Communitarianism, (The Spirit of Community, Amitai Etzioni)

- Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (Community and Society, Ferdinand Tönnies)

- Imagined communities

- Interest network

- Online participation

- Social solidarity

- Community practice (Social Work)

- http://www.wright-house.com/psychology/sense-of-community.html Psychological Sense of Community]: Theory of McMillan & Chavis.

The Neighborhood

- YouTube Video: Sesame Street: Ben Stiller Sings About Friends & Neighbors

- YouTube Video: What's it Like Living in the 'Hood

- YouTube Video: Top 10 Best U.S. Suburbs to Live in

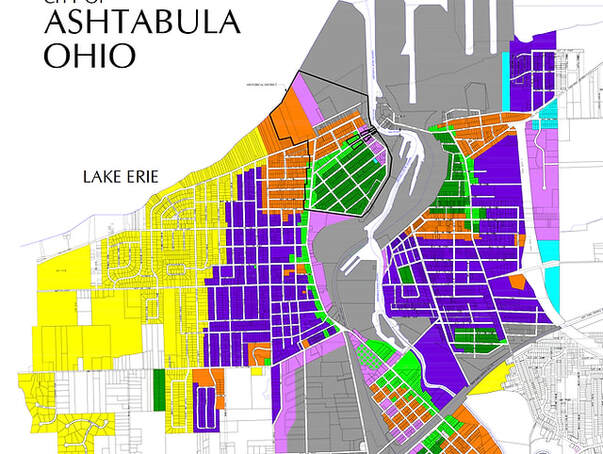

A neighbourhood (British English, Australian English and Canadian English) or neighborhood (American English; see spelling differences) is a geographically localized community within a larger city, town, suburb or rural area. Neighborhoods are often social communities with considerable face-to-face interaction among members.

Researchers have not agreed on an exact definition, but the following may serve as a starting point: "Neighborhood is generally defined spatially as a specific geographic area and functionally as a set of social networks. Neighborhoods, then, are the spatial units in which face-to-face social interactions occur—the personal settings and situations where residents seek to realize common values, socialize youth, and maintain effective social control."

Preindustrial cities:

In the words of the urban scholar Lewis Mumford, “Neighborhoods, in some annoying, inchoate fashion exist wherever human beings congregate, in permanent family dwellings; and many of the functions of the city tend to be distributed naturally—that is, without any theoretical preoccupation or political direction—into neighborhoods.” Most of the earliest cities around the world as excavated by archaeologists have evidence for the presence of social neighborhoods. Historical documents shed light on neighborhood life in numerous historical preindustrial or nonwestern cities.

Neighborhoods are typically generated by social interaction among people living near one another. In this sense they are local social units larger than households not directly under the control of city or state officials. In some preindustrial urban traditions, basic municipal functions such as protection, social regulation of births and marriages, cleaning and upkeep are handled informally by neighborhoods and not by urban governments; this pattern is well documented for historical Islamic cities.

In addition to social neighborhoods, most ancient and historical cities also had administrative districts used by officials for taxation, record-keeping, and social control.

Administrative districts are typically larger than neighborhoods and their boundaries may cut across neighborhood divisions. In some cases, however, administrative districts coincided with neighborhoods, leading to a high level of regulation of social life by officials. For example, in the T’ang period Chinese capital city Chang’an, neighborhoods were districts and there were state officials who carefully controlled life and activity at the neighbouhood level.

Neighborhoods in preindustrial cities often had some degree of social specialization or differentiation. Ethnic neighborhoods were important in many past cities and remain common in cities today. Economic specialists, including craft producers, merchants, and others, could be concentrated in neighborhoods, and in societies with religious pluralism neighborhoods were often specialized by religion.

One factor contributing to neighborhood distinctiveness and social cohesion in past cities was the role of rural to urban migration. This was a continual process in preindustrial cities, and migrants tended to move in with relatives and acquaintances from their rural past.

Sociology:

Neighborhood sociology is a subfield of urban sociology which studies local communities Neighborhoods are also used in research studies from postal codes and health disparities, to correlations with school drop out rates or use of drugs. Some attention has also been devoted to viewing the neighborhood as a small-scale democracy, regulated primarily by ideas of reciprocity among neighbors.

Improvement:

Neighbourhoods have been the site of service delivery or "service interventions" in part as efforts to provide local, quality services, and to increase the degree of local control and ownership. Alfred Kahn, as early as the mid-1970s, described the "experience, theory and fads" of neighborhood service delivery over the prior decade, including discussion of income transfers and poverty.

Neighborhoods, as a core aspect of community, also are the site of services for youth, including children with disabilities and coordinated approaches to low-income populations. While the term neighborhood organization is not as common in 2015, these organizations often are non-profit, sometimes grassroots or even core funded community development centers or branches.

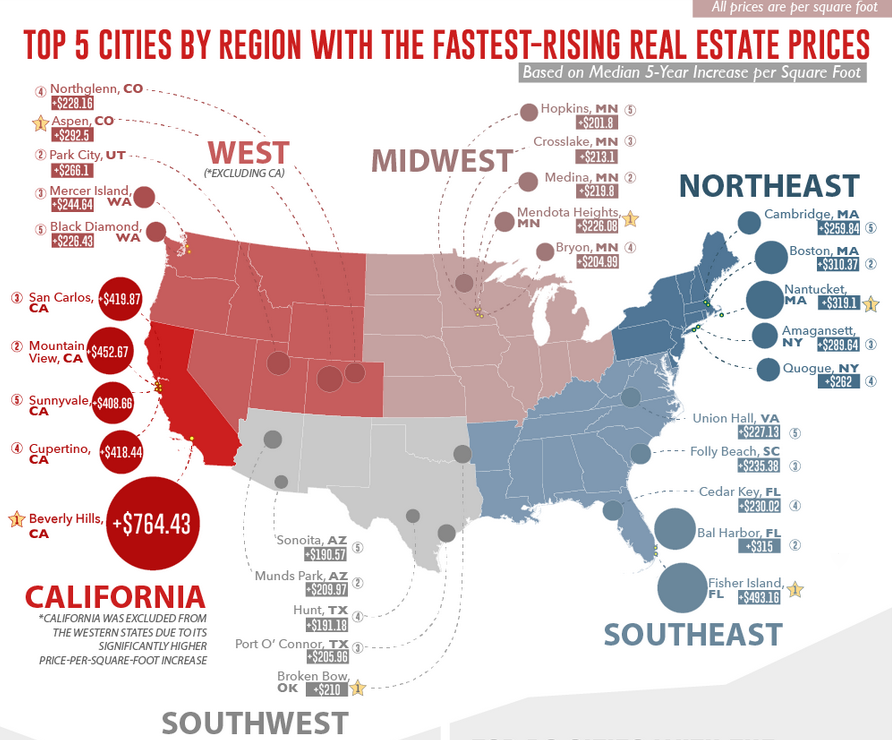

Community and economic development activists have pressured for reinvestment in local communities and neighborhoods. In the early 2000s, Community Development Corporations, Rehabilitation Networks, Neighborhood Development Corporations, and Economic Development organizations would work together to address the housing stock and the infrastructures of communities and neighborhoods (e.g., community centers).

Community and Economic Development may be understood in different ways, and may involve "faith-based" groups and congregations in cities.

As a unit in urban design:

In the 1900s, Clarence Perry described the idea of a neighborhood unit as a self-contained residential area within a city. The concept is still influential in New Urbanism. Practitioners seek to revive traditional sociability in planned suburban housing based on a set of principles. At the same time, the neighbourhood is a site of interventions to create Age-Friendly Cities and Communities (AFCC) as many older adults tend to have narrower life space. Urban design studies thus use neighborhood as a unit of analysis.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Neighborhoods:

Researchers have not agreed on an exact definition, but the following may serve as a starting point: "Neighborhood is generally defined spatially as a specific geographic area and functionally as a set of social networks. Neighborhoods, then, are the spatial units in which face-to-face social interactions occur—the personal settings and situations where residents seek to realize common values, socialize youth, and maintain effective social control."

Preindustrial cities:

In the words of the urban scholar Lewis Mumford, “Neighborhoods, in some annoying, inchoate fashion exist wherever human beings congregate, in permanent family dwellings; and many of the functions of the city tend to be distributed naturally—that is, without any theoretical preoccupation or political direction—into neighborhoods.” Most of the earliest cities around the world as excavated by archaeologists have evidence for the presence of social neighborhoods. Historical documents shed light on neighborhood life in numerous historical preindustrial or nonwestern cities.

Neighborhoods are typically generated by social interaction among people living near one another. In this sense they are local social units larger than households not directly under the control of city or state officials. In some preindustrial urban traditions, basic municipal functions such as protection, social regulation of births and marriages, cleaning and upkeep are handled informally by neighborhoods and not by urban governments; this pattern is well documented for historical Islamic cities.

In addition to social neighborhoods, most ancient and historical cities also had administrative districts used by officials for taxation, record-keeping, and social control.

Administrative districts are typically larger than neighborhoods and their boundaries may cut across neighborhood divisions. In some cases, however, administrative districts coincided with neighborhoods, leading to a high level of regulation of social life by officials. For example, in the T’ang period Chinese capital city Chang’an, neighborhoods were districts and there were state officials who carefully controlled life and activity at the neighbouhood level.

Neighborhoods in preindustrial cities often had some degree of social specialization or differentiation. Ethnic neighborhoods were important in many past cities and remain common in cities today. Economic specialists, including craft producers, merchants, and others, could be concentrated in neighborhoods, and in societies with religious pluralism neighborhoods were often specialized by religion.

One factor contributing to neighborhood distinctiveness and social cohesion in past cities was the role of rural to urban migration. This was a continual process in preindustrial cities, and migrants tended to move in with relatives and acquaintances from their rural past.

Sociology:

Neighborhood sociology is a subfield of urban sociology which studies local communities Neighborhoods are also used in research studies from postal codes and health disparities, to correlations with school drop out rates or use of drugs. Some attention has also been devoted to viewing the neighborhood as a small-scale democracy, regulated primarily by ideas of reciprocity among neighbors.

Improvement:

Neighbourhoods have been the site of service delivery or "service interventions" in part as efforts to provide local, quality services, and to increase the degree of local control and ownership. Alfred Kahn, as early as the mid-1970s, described the "experience, theory and fads" of neighborhood service delivery over the prior decade, including discussion of income transfers and poverty.

Neighborhoods, as a core aspect of community, also are the site of services for youth, including children with disabilities and coordinated approaches to low-income populations. While the term neighborhood organization is not as common in 2015, these organizations often are non-profit, sometimes grassroots or even core funded community development centers or branches.

Community and economic development activists have pressured for reinvestment in local communities and neighborhoods. In the early 2000s, Community Development Corporations, Rehabilitation Networks, Neighborhood Development Corporations, and Economic Development organizations would work together to address the housing stock and the infrastructures of communities and neighborhoods (e.g., community centers).

Community and Economic Development may be understood in different ways, and may involve "faith-based" groups and congregations in cities.

As a unit in urban design:

In the 1900s, Clarence Perry described the idea of a neighborhood unit as a self-contained residential area within a city. The concept is still influential in New Urbanism. Practitioners seek to revive traditional sociability in planned suburban housing based on a set of principles. At the same time, the neighbourhood is a site of interventions to create Age-Friendly Cities and Communities (AFCC) as many older adults tend to have narrower life space. Urban design studies thus use neighborhood as a unit of analysis.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Neighborhoods:

- Neighbourhoods around the world

- See also:

- Barangay (Philippines)

- Barrio (Spanish)

- Bairro (Portuguese)

- Block Parent Program (Canada)

- Borough

- Census-designated place

- Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (Cuba)

- Comparison of Home Owners' and Civic Associations

- Frazione (Italian)

- Homeowners' association

- Kiez (German)

- Komshi (Balkan states during the Ottoman Empire)

- Mahalle

- Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

- Neighborhood Watch

- New urbanism

- Electoral precinct

- Quarter

- Quartiere

- Residential community

- Suburbs

- Unincorporated community

Community Development

- YouTube Video: What is COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT? What does COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT mean?

- YouTube Video: Sustainable community development: from what's wrong to what's strong | Cormac Russell | TEDxExeter

- YouTube Video: How a Community Development Experience Can Change Your Life | David Luther | TEDxBerkeleyPrep

The United Nations defines community development as "a process where community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems." It is a broad concept, applied to the practices of civic leaders, activists, involved citizens, and professionals to improve various aspects of communities, typically aiming to build stronger and more resilient local communities.

Community development is also understood as a professional discipline, and is defined by the International Association for Community Development as "a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes participative democracy, sustainable development, rights, economic opportunity, equality and social justice, through the organization, education and empowerment of people within their communities, whether these be of locality, identity or interest, in urban and rural settings".

Community development seeks to empower individuals and groups of people with the skills they need to effect change within their communities. These skills are often created through the formation of social groups working for a common agenda. Community developers must understand both how to work with individuals and how to affect communities' positions within the context of larger social institutions.

Community development as a term has taken off widely in anglophone countries, i.e. the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, as well as other countries in the Commonwealth of Nations. It is also used in some countries in Eastern Europe with active community development associations in Hungary and Romania.

The Community Development Journal, published by Oxford University Press, since 1966 has aimed to be the major forum for research and dissemination of international community development theory and practice.

Community development approaches are recognized internationally. These methods and approaches have been acknowledged as significant for local social, economic, cultural, environmental and political development by such organizations as the UN, WHO, OECD, World Bank, Council of Europe and EU.

There are a number of institutions of higher education offer community development as an area of study and research such as the University of Toronto, Leiden University, SOAS University of London, and the Balsillie School of International Affairs, among others.

Definitions:

There are complementary definitions of community development.

The United Nations defines community development broadly as "a process where community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems." and the International Association for Community Development defines it as both a practice based profession and an academic discipline.

Following the adoption of the IACD definition in 2016, the association has gone on to produce International Standards for Community Development Practice. The values and ethos that should underpin practice can be expressed as: Commitment to rights, solidarity, democracy, equality, environmental and social justice.

The purpose of community development is understood by IACD as being to work with communities to achieve participative democracy, sustainable development, rights, economic opportunity, equality and social justice.

This practice is carried out by people in different roles and contexts, including people explicitly called professional community workers (and people taking on essentially the same role but with a different job title), together with professionals in other occupations ranging from:

Community development practice also encompasses a range of occupational settings and levels from development roles working with communities, through to managerial and strategic community planning roles.

The Community Development Challenge report, which was produced by a working party comprising leading UK organizations in the field including the (now defunct) Community Development Foundation, the (now defunct) Community Development Exchange and the (now defunct) Federation for Community Development Learning defines community development as:

A set of values and practices which plays a special role in overcoming poverty and disadvantage, knitting society together at the grass roots and deepening democracy. There is a community development profession, defined by national occupational standards and a body of theory and experience going back the best part of a century.

There are active citizens who use community development techniques on a voluntary basis, and there are also other professions and agencies which use a community development approach or some aspects of it.

Community Development Exchange defines community development as:

both an occupation (such as a community development worker in a local authority) and a way of working with communities. Its key purpose is to build communities based on justice, equality and mutual respect.

Community development involves changing the relationships between ordinary people and people in positions of power, so that everyone can take part in the issues that affect their lives. It starts from the principle that within any community there is a wealth of knowledge and experience which, if used in creative ways, can be channeled into collective action to achieve the communities' desired goals.

Community development practitioners work alongside people in communities to help build relationships with key people and organizations and to identify common concerns. They create opportunities for :the community to learn new skills and, by enabling people to act together, community development practitioners help to foster social inclusion and equality.

Different approaches:

There are numerous overlapping approaches to community development. Some focus on the processes, some on the outcomes/ objectives. They include:

There are a myriad of job titles for community development workers and their employers include public authorities and voluntary or non-governmental organisations, funded by the state and by independent grant making bodies. Since the nineteen seventies the prefix word 'community' has also been adopted by several other occupations from the police and health workers to planners and architects, who have been influenced by community development approaches.

History:

Amongst the earliest community development approaches were those developed in Kenya and British East Africa during the 1930s. Community development practitioners have over many years developed a range of approaches for working within local communities and in particular with disadvantaged people.

Since the nineteen sixties and seventies through the various anti poverty programmes in both developed and developing countries, community development practitioners have been influenced by structural analyses as to the causes of disadvantage and poverty i.e. inequalities in the distribution of wealth, income, land, etc. and especially political power and the need to mobilize people power to affect social change.

Thus the influence of such educators as Paulo Freire and his focus upon this work. Other key people who have influenced this field are Saul Alinsky (Rules for Radicals) and E.F. Schumacher (Small Is Beautiful).

There are a number of international organizations that support community development, for example, Oxfam, UNICEF, The Hunger Project and Freedom from Hunger, run community development programs based upon community development initiatives for relief and prevention of malnutrition. Since 2006 the Dragon Dreaming Project Management techniques have spread to 37 different countries and are engaged in an estimated 3,250 projects worldwide.

In the global North:

In the 19th century, the work of the Welsh early socialist thinker Robert Owen (1771–1851), sought to create a more perfect community. At New Lanark and at later communities such as Oneida in the USA and the New Australia Movement in Australia, groups of people came together to create utopian or intentional communities, with mixed success.

United States: In the United States in the 1960s, the term "community development" began to complement and generally replace the idea of urban renewal, which typically focused on physical development projects often at the expense of working-class communities.

One of the earliest proponents of the term in the United States was social scientist William W. Biddle In the late 1960s, philanthropies such as the Ford Foundation and government officials such as Senator Robert F. Kennedy took an interest in local nonprofit organizations.

A pioneer was the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation in Brooklyn, which attempted to apply business and management skills to the social mission of uplifting low-income residents and their neighborhoods. Eventually such groups became known as "Community development corporations" or CDCs. Federal laws beginning with the 1974 Housing and Community Development Act provided a way for state and municipal governments to channel funds to CDCs and other nonprofit organizations.

National organizations such as the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation (founded in 1978 and now known as NeighborWorks America), the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) (founded in 1980), and the Enterprise Foundation (founded in 1981) have built extensive networks of affiliated local nonprofit organizations to which they help provide financing for countless physical and social development programs in urban and rural communities.

The CDCs and similar organizations have been credited with starting the process that stabilized and revived seemingly hopeless inner city areas such as the South Bronx in New York City.

United Kingdom: In the UK, community development has had two main traditions. The first was as an approach for preparing for the independence of countries from the former British Empire in the 1950s and 1960s. Domestically it first came into public prominence with the Labour Government's anti deprivation programs of the latter sixties and seventies.

The main example of this being the CDP (Community Development Programme), which piloted local area based community development. This influenced a number of largely urban local authorities, in particular in Scotland with Strathclyde Region's major community development programme (the largest at the time in Europe).

The Gulbenkian Foundation was a key funder of commissions and reports which influenced the development of community development in the UK from the latter sixties to the 80's. This included recommending that there be a national institute or centre for community development, able to support practice and to advise government and local authorities on policy.

This was formally set up in 1991 as the Community Development Foundation. In 2004 the Carnegie UK Trust established a Commission of Inquiry into the future of rural community development examining such issues as land reform and climate change. Carnegie funded over sixty rural community development action research projects across the UK and Ireland and national and international communities of practice to exchange experiences. This included the International Association for Community Development.

In 1999 a UK wide organization responsible for setting professional training standards for all education and development practitioners working within local communities was established and recognized by the Labour Government. This organization was called PAULO – the National Training Organization for Community Learning and Development. (It was named after Paulo Freire). It was formally recognized by David Blunkett, the Secretary of State for Education and Employment.

Its first chair was Charlie McConnell, the Chief Executive of the Scottish Community Education Council, who had played a lead role in bringing together a range of occupational interests under a single national training standards body, including community education, community development and development education.

The inclusion of community development was significant as it was initially uncertain as to whether it would join the NTO for Social Care. The Community Learning and Development NTO represented all the main employers, trades unions, professional associations and national development agencies working in this area across the four nations of the UK.

The term 'community learning and development' was adopted to acknowledge that all of these occupations worked primarily within local communities, and that this work encompassed not just providing less formal learning support but also a concern for the wider holistic development of those communities – socio-economically, environmentally, culturally and politically.

By bringing together these occupational groups this created for the first time a single recognised employment sector of nearly 300,000 full and part-time paid staff within the UK, approximately 10% of these staff being full-time. The NTO continued to recognise the range of different occupations within it, for example specialists who work primarily with young people, but all agreed that they shared a core set of professional approaches to their work. In 2002 the NTO became part of a wider Sector Skills Council for lifelong learning.

The UK currently hosts the only global network of practitioners and activists working towards social justice through community development approach, the International Association for Community Development (IACD). IACD was formed in the USA in 1953, moved to Belgium in 1978 and was restructured and relaunched in Scotland in 1999.

Canada: Community development in Canada has roots in the development of co-operatives, credit unions and caisses populaires. The Antigonish Movement which started in the 1920s in Nova Scotia, through the work of Doctor Moses Coady and Father James Tompkins, has been particularly influential in the subsequent expansion of community economic development work across Canada.

Australia: Community development in Australia have often been focussed upon Aboriginal Australian communities, and during the period of the 1980s to the early 21st century were funded through the Community Employment Development Program, where Aboriginal people could be employed in "a work for the dole" scheme, which gave the chance for non-government organisations to apply for a full or part-time worker funded by the Department for Social Security. Dr Jim Ife, formerly of Curtin University, organized a ground breaking text-book on community development

In the "Global South":

Community planning techniques drawing on the history of utopian movements became important in the 1920s and 1930s in East Africa, where community development proposals were seen as a way of helping local people improve their own lives with indirect assistance from colonial authorities.

Mohandas K. Gandhi adopted African community development ideals as a basis of his South African Ashram, and then introduced it as a part of the Indian Swaraj movement, aiming at establishing economic interdependence at village level throughout India. With Indian independence, despite the continuing work of Vinoba Bhave in encouraging grassroots land reform, India under its first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru adopted a mixed-economy approach, mixing elements of socialism and capitalism.

During the fifties and sixties, India ran a massive community development programme with focus on rural development activities through government support. This was later expanded in scope and was called integrated rural development scheme [IRDP]. A large number of initiatives that can come under the community development umbrella have come up in recent years.

The main objective of community development in India remains to develop the villages and to help the villagers help themselves to fight against poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition, etc. The beauty of Indian model of community development lies in the homogeneity of villagers and high level of participation.

Community development became a part of the Ujamaa Villages established in Tanzania by Julius Nyerere, where it had some success in assisting with the delivery of education services throughout rural areas, but has elsewhere met with mixed success.

In the 1970s and 1980s, community development became a part of "Integrated Rural Development", a strategy promoted by United Nations Agencies and the World Bank. Central to these policies of community development were:

In the 1990s, following critiques of the mixed success of "top down" government programs, and drawing on the work of Robert Putnam, in the rediscovery of social capital, community development internationally became concerned with social capital formation. In particular the outstanding success of the work of Muhammad Yunus in Bangladesh with the Grameen Bank from its inception in 1976, has led to the attempts to spread microenterprise credit schemes around the world.

Yunus saw that social problems like poverty and disease were not being solved by the market system on its own. Thus, he established a banking system which lends to the poor with very little interest, allowing them access to entrepreneurship. This work was honored by the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize.

Another alternative to "top down" government programs is the participatory government institution. Participatory governance institutions are organizations which aim to facilitate the participation of citizens within larger decision making and action implementing processes in society. A case study done on municipal councils and social housing programs in Brazil found that the presence of participatory governance institutions supports the implementation of poverty alleviation programs by local governments.

The "human scale development" work of Right Livelihood Award-winning Chilean economist Manfred Max Neef promotes the idea of development based upon fundamental human needs, which are considered to be limited, universal and invariant to all human beings (being a part of our human condition). He considers that poverty results from the failure to satisfy a particular human need, it is not just an absence of money.

Whilst human needs are limited, Max Neef shows that the ways of satisfying human needs is potentially unlimited. Satisfiers also have different characteristics: they can be violators or destroyers, pseudosatisfiers, inhibiting satisfiers, singular satisfiers, or synergic satisfiers.

Max-Neef shows that certain satisfiers, promoted as satisfying a particular need, in fact inhibit or destroy the possibility of satisfying other needs: e.g., the arms race, while ostensibly satisfying the need for protection, in fact then destroys subsistence, participation, affection and freedom; formal democracy, which is supposed to meet the need for participation often disempowers and alienates; commercial television, while used to satisfy the need for recreation, interferes with understanding, creativity and identity.

Synergic satisfiers, on the other hand, not only satisfy one particular need, but also lead to satisfaction in other areas: some examples are:

India: Community development in India was initiated by Government of India through Community Development Programme (CDP) in 1952. The focus of CDP was on rural communities. But, professionally trained social workers concentrated their practice in urban areas. Thus, although the focus of community organization was rural, the major thrust of Social Work gave an urban character which gave a balance in service for the program.

Vietnam: International organizations apply the term community in Vietnam to the local administrative unit, each with a traditional identity based on traditional, cultural, and kinship relations. Community development strategies in Vietnam aim to organize communities in ways that increase their capacities to partner with institutions, the participation of local people, transparency and equality, and unity within local communities.

Social and economic development planning (SDEP) in Vietnam uses top-down centralized planning methods and decision-making processes which do not consider local context and local participation. The plans created by SDEP are ineffective and serve mainly for administrative purposes. Local people are not informed of these development plans.

The participatory rural appraisal (PRA) approach, a research methodology that allows local people to share and evaluate their own life conditions, was introduced to Vietnam in the early 1990s to help reform the way that government approaches local communities and development. PRA was used as a tool for mostly outsiders to learn about the local community, which did not effect substantial change.

The village/commune development (VDP/CDP) approach was developed as a more fitting approach than PRA to analyze local context and address the needs of rural communities.[29] VDP/CDP participatory planning is centered around Ho Chi Minh's saying that "People know, people discuss and people supervise." VDP/CDP is often useful in Vietnam for shifting centralized management to more decentralization, helping develop local governance at the grassroots level.

Local people use their knowledge to solve local issues. They create mid-term and yearly plans that help improve existing community development plans with the support of government organizations. Although VDP/CDP has been tested in many regions in Vietnam, it has not been fully implemented for a couple reasons. The methods applied in VDP/CDP are human resource and capacity building intensive, especially at the early stages.