Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

This Web Page covers

Wars and Other Military Conflicts

whether between Countries,

or Internal Civil Wars, including civilian and military targets

See Also:

The Worst of Humanity

Democracy in the United States

Politics

United States Military

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

TOP: Vladmir Putin and 3 ways the Russian invasion of Ukraine is already screwing up the world economy

BOTTOM: Russian forces attacking Kyiv, explosions heard in Ukrainian capital

- YouTube Video: Russian invasion | 'Leave now or face threat of death,' Ukraine's message to residents | World News

- YouTube Video: Day 24 of the Russian invasion of Ukraine: Russia uses Kinzhal hypersonic missile

- YouTube Video: Russia-Ukraine War Day 30: Top Haunting Images From Russian Invasion Of Ukraine

TOP: Vladmir Putin and 3 ways the Russian invasion of Ukraine is already screwing up the world economy

BOTTOM: Russian forces attacking Kyiv, explosions heard in Ukrainian capital

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Internationally considered an act of aggression, the invasion has triggered Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II, with more than 4.3 million Ukrainians leaving the country, and a quarter of the population displaced.

The invasion marked a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began following the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity. Russia subsequently annexed Crimea, and Russian-backed separatists seized part of the south-eastern Donbas region of Ukraine, sparking a war there.

In 2021, Russia began a large military build-up along its border with Ukraine, amassing up to 190,000 troops along with their equipment. In a broadcast shortly before the invasion, Russian president Vladimir Putin espoused irredentist views, questioned Ukraine's right to statehood, and falsely accused Ukraine of being dominated by neo-Nazis who persecute the ethnic Russian minority.

Putin said that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), by expanding eastward since the early 2000s, had threatened Russia's security – a claim disputed by NATO – and demanded Ukraine be barred from ever joining the alliance.

The United States and others accused Russia of planning to attack or invade Ukraine, which Russian officials repeatedly denied as late as 23 February 2022.

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognized the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic, two self-proclaimed statelets in Donbas controlled by pro-Russian separatists. The following day, the Federation Council of Russia authorized the use of military force abroad, and overt Russian troops entered both territories.

The invasion began on the morning of 24 February, when Putin announced a "special military operation" to "demilitarize and denazify" Ukraine. Minutes later, missiles and airstrikes hit across Ukraine, including the capital Kyiv, shortly followed by a large ground invasion from multiple directions.

In response, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy enacted martial law and general mobilization.

Multi-pronged offensives were launched from Russia, Belarus, and the two occupied territories of Ukraine (Crimea and Donbas). The four major offensives are:

Russian aircraft and missiles also struck western parts of Ukraine. Russian forces have approached or besieged key settlements, including Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Kyiv, Mariupol, and Sumy, but met stiff Ukrainian resistance and experienced logistical and operational challenges that hampered their progress.

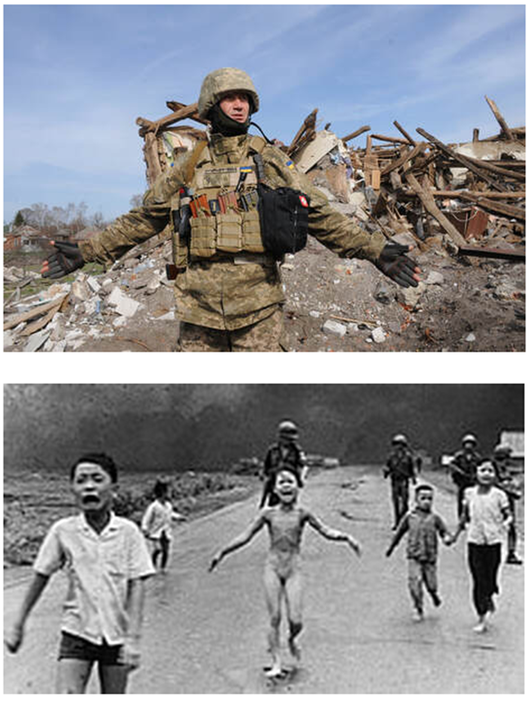

Three weeks after launching the invasion, the Russian military had more success in the south, while incremental gains or stalemates elsewhere forced them into attrition warfare, resulting in mounting civilian casualties. In late March 2022, Russian forces withdrew from the Kyiv region with the declared aim to refocus on Donbas, leaving behind devastated settlements and growing evidence of atrocities against civilians.

The invasion has been widely condemned internationally. The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution which condemned it and demanded a full withdrawal.

The International Court of Justice ordered Russia to suspend military operations and the Council of Europe expelled Russia. Many countries imposed new sanctions, which have affected the economies of Russia and the world, and provided humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine.

Protests occurred around the world; those in Russia have been met with mass arrests and increased media censorship, including banning the terms "war" and "invasion".

Numerous companies withdrew their products and services from Russia and Belarus, and Russian state-funded media were banned from broadcasting and removed from online platforms.

The International Criminal Court opened an investigation into allegations of Russian military war crimes in Ukraine.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine by Russia:

Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Internationally considered an act of aggression, the invasion has triggered Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II, with more than 4.3 million Ukrainians leaving the country, and a quarter of the population displaced.

The invasion marked a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began following the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity. Russia subsequently annexed Crimea, and Russian-backed separatists seized part of the south-eastern Donbas region of Ukraine, sparking a war there.

In 2021, Russia began a large military build-up along its border with Ukraine, amassing up to 190,000 troops along with their equipment. In a broadcast shortly before the invasion, Russian president Vladimir Putin espoused irredentist views, questioned Ukraine's right to statehood, and falsely accused Ukraine of being dominated by neo-Nazis who persecute the ethnic Russian minority.

Putin said that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), by expanding eastward since the early 2000s, had threatened Russia's security – a claim disputed by NATO – and demanded Ukraine be barred from ever joining the alliance.

The United States and others accused Russia of planning to attack or invade Ukraine, which Russian officials repeatedly denied as late as 23 February 2022.

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognized the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic, two self-proclaimed statelets in Donbas controlled by pro-Russian separatists. The following day, the Federation Council of Russia authorized the use of military force abroad, and overt Russian troops entered both territories.

The invasion began on the morning of 24 February, when Putin announced a "special military operation" to "demilitarize and denazify" Ukraine. Minutes later, missiles and airstrikes hit across Ukraine, including the capital Kyiv, shortly followed by a large ground invasion from multiple directions.

In response, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy enacted martial law and general mobilization.

Multi-pronged offensives were launched from Russia, Belarus, and the two occupied territories of Ukraine (Crimea and Donbas). The four major offensives are:

- the Kyiv offensive,

- the Northeastern Ukraine offensive,

- the Eastern Ukraine offensive,

- and the Southern Ukraine offensive.

Russian aircraft and missiles also struck western parts of Ukraine. Russian forces have approached or besieged key settlements, including Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Kyiv, Mariupol, and Sumy, but met stiff Ukrainian resistance and experienced logistical and operational challenges that hampered their progress.

Three weeks after launching the invasion, the Russian military had more success in the south, while incremental gains or stalemates elsewhere forced them into attrition warfare, resulting in mounting civilian casualties. In late March 2022, Russian forces withdrew from the Kyiv region with the declared aim to refocus on Donbas, leaving behind devastated settlements and growing evidence of atrocities against civilians.

The invasion has been widely condemned internationally. The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution which condemned it and demanded a full withdrawal.

The International Court of Justice ordered Russia to suspend military operations and the Council of Europe expelled Russia. Many countries imposed new sanctions, which have affected the economies of Russia and the world, and provided humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine.

Protests occurred around the world; those in Russia have been met with mass arrests and increased media censorship, including banning the terms "war" and "invasion".

Numerous companies withdrew their products and services from Russia and Belarus, and Russian state-funded media were banned from broadcasting and removed from online platforms.

The International Criminal Court opened an investigation into allegations of Russian military war crimes in Ukraine.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine by Russia:

- Background

- Prelude

- Invasion and resistance

- Foreign military involvement

- Casualties and humanitarian impact

- Legal implications

- Peace efforts

- Media depictions

- Sanctions and ramifications

- Reactions

- See also:

- Timeline of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- List of interstate wars since 1945

- List of ongoing armed conflicts

- List of military engagements during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Post-Soviet conflicts – Military conflicts in the former Soviet Union

- Russo-Georgian War – 2008 conflict between Russia and Georgia

- Transnistria War – 1990–1992 conflict between Moldova and Russian-backed self-proclaimed Transnistria

- Second Cold War – Post–Cold War era term

- World War III – Hypothetical future global conflict

- Media related to 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine at Wikimedia Commons

- Russia invades Ukraine live updates. CNN.

- Ukraine live updates. BBC News.

- Video of aftermath, including injured pregnant woman being carried, after Russian airstrike on hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine. Sky News, March 9, 2022

- Russia invades Ukraine. Reuters, 10 March 2022

- Video archive by RFE/RL

- Tracking Social Media Takedowns and Content Moderation During the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine (updated weekly)

War vs. Proxy Wars

- YouTube Video: US Foreign Wars (1950-2019) – Fighting the Last War

- YouTube Video: The American Civil War - OverSimplified

- YouTube Video: What is PROXY WAR? What does PROXY WAR mean?

WAR:

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, aggression, destruction, and mortality, using regular or irregular military forces.

Warfare refers to the common activities and characteristics of types of war, or of wars in general. Total war is warfare that is not restricted to purely legitimate military targets, and can result in massive civilian or other non-combatant suffering and casualties.

While some war studies scholars consider war a universal and ancestral aspect of human nature, others argue it is a result of specific socio-cultural, economic or ecological circumstances.

The English word war derives from the 11th-century Old English words wyrre and werre, from Old French werre (also guerre as in modern French), in turn from the Frankish *werra, ultimately deriving from the Proto-Germanic *werzō 'mixture, confusion'. The word is related to the Old Saxon werran, Old High German werran, and the German verwirren, meaning "to confuse", "to perplex", and "to bring into confusion".

History:

Main article: Military history

The earliest evidence of prehistoric warfare is a Mesolithic cemetery in Jebel Sahaba, which has been determined to be approximately 14,000 years old. About forty-five percent of the skeletons there displayed signs of violent death.

Since the rise of the state some 5,000 years ago, military activity has occurred over much of the globe. The advent of gunpowder and the acceleration of technological advances led to modern warfare. According to Conway W. Henderson, "One source claims that 14,500 wars have taken place between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, costing 3.5 billion lives, leaving only 300 years of peace (Beer 1981: 20)."

An unfavorable review of this estimate mentions the following regarding one of the proponents of this estimate: "In addition, perhaps feeling that the war casualties figure was improbably high, he changed 'approximately 3,640,000,000 human beings have been killed by war or the diseases produced by war' to 'approximately 1,240,000,000 human beings...&c.'"

The lower figure is more plausible, but could still be on the high side considering that the 100 deadliest acts of mass violence between 480 BC and 2002 AD (wars and other man-made disasters with at least 300,000 and up to 66 million victims) claimed about 455 million human lives in total.

Primitive warfare is estimated to have accounted for 15.1% of deaths and claimed 400 million victims. Added to the aforementioned figure of 1,240 million between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, this would mean a total of 1,640,000,000 people killed by war (including deaths from famine and disease caused by war) throughout the history and pre-history of mankind. For comparison, an estimated 1,680,000,000 people died from infectious diseases in the 20th century.

In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, says approximately 90–95% of known societies throughout history engaged in at least occasional warfare, and many fought constantly.

Keeley describes several styles of primitive combat such as small raids, large raids, and massacres. All of these forms of warfare were used by primitive societies, a finding supported by other researchers. Keeley explains that early war raids were not well organized, as the participants did not have any formal training. Scarcity of resources meant defensive works were not a cost-effective way to protect the society against enemy raids.

William Rubinstein wrote "Pre-literate societies, even those organised in a relatively advanced way, were renowned for their studied cruelty...'archaeology yields evidence of prehistoric massacres more severe than any recounted in ethnography [i.e., after the coming of the Europeans].'"

In Western Europe, since the late 18th century, more than 150 conflicts and about 600 battles have taken place. During the 20th century, war resulted in a dramatic intensification of the pace of social changes, and was a crucial catalyst for the emergence of the political Left as a force to be reckoned with.

In 1947, in view of the rapidly increasingly destructive consequences of modern warfare, and with a particular concern for the consequences and costs of the newly developed atom bomb, Albert Einstein famously stated, "I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones."

Mao Zedong urged the socialist camp not to fear nuclear war with the United States since, even if "half of mankind died, the other half would remain while imperialism would be razed to the ground and the whole world would become socialist."

A distinctive feature of war since 1945 is the absence of wars between major powers—indeed the near absence of any traditional wars between established countries. The major exceptions were the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the Iran–Iraq War 1980–1988, and the Gulf War of 1990–91. Instead, combat has largely been a matter of civil wars and insurgencies.

The Human Security Report 2005 documented a significant decline in the number and severity of armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s (see below). However, the evidence examined in the 2008 edition of the Center for International Development and Conflict Management's "Peace and Conflict" study indicated the overall decline in conflicts had stalled.

Types of warfare:

Main article: Types of war

Aims:

Entities contemplating going to war and entities considering whether to end a war may formulate war aims as an evaluation/propaganda tool. War aims may stand as a proxy for national-military resolve.

Definition:

Fried defines war aims as "the desired territorial, economic, military or other benefits expected following successful conclusion of a war".

Classification:

Tangible/intangible aims:

Explicit/implicit aims:

Positive/negative aims:

War aims can change in the course of conflict and may eventually morph into "peace conditions" – the minimal conditions under which a state may cease to wage a particular war.

Effects:

Main article: Effects of war

Military and civilian casualties in recent human history:

Throughout the course of human history, the average number of people dying from war has fluctuated relatively little, being about 1 to 10 people dying per 100,000. However, major wars over shorter periods have resulted in much higher casualty rates, with 100-200 casualties per 100,000 over a few years.

While conventional wisdom holds that casualties have increased in recent times due to technological improvements in warfare, this is not generally true. For instance, the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) had about the same number of casualties per capita as World War I, although it was higher during World War II (WWII). That said, overall the number of casualties from war has not significantly increased in recent times. Quite to the contrary, on a global scale the time since WWII has been unusually peaceful.

Largest by death toll:

Main articles:

The deadliest war in history, in terms of the cumulative number of deaths since its start, is World War II, from 1939 to 1945, with 60–85 million deaths, followed by the Mongol conquests at up to 60 million.

As concerns a belligerent's losses in proportion to its prewar population, the most destructive war in modern history may have been the Paraguayan War (see Paraguayan War casualties).

In 2013 war resulted in 31,000 deaths, down from 72,000 deaths in 1990. In 2003, Richard Smalley identified war as the sixth biggest problem (of ten) facing humanity for the next fifty years. War usually results in significant deterioration of infrastructure and the ecosystem, a decrease in social spending, famine, large-scale emigration from the war zone, and often the mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilians.

For instance, of the nine million people who were on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR in 1941, some 1.6 million were killed by the Germans in actions away from battlefields, including about 700,000 prisoners of war, 500,000 Jews, and 320,000 people counted as partisans (the vast majority of whom were unarmed civilians). Another byproduct of some wars is the prevalence of propaganda by some or all parties in the conflict, and increased revenues by weapons manufacturers.

Three of the ten most costly wars, in terms of loss of life, have been waged in the last century. These are the two World Wars, followed by the Second Sino-Japanese War (which is sometimes considered part of World War II, or as overlapping).

Most of the others involved China or neighboring peoples. The death toll of World War II, being over 60 million, surpasses all other war-death-tolls:

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, aggression, destruction, and mortality, using regular or irregular military forces.

Warfare refers to the common activities and characteristics of types of war, or of wars in general. Total war is warfare that is not restricted to purely legitimate military targets, and can result in massive civilian or other non-combatant suffering and casualties.

While some war studies scholars consider war a universal and ancestral aspect of human nature, others argue it is a result of specific socio-cultural, economic or ecological circumstances.

The English word war derives from the 11th-century Old English words wyrre and werre, from Old French werre (also guerre as in modern French), in turn from the Frankish *werra, ultimately deriving from the Proto-Germanic *werzō 'mixture, confusion'. The word is related to the Old Saxon werran, Old High German werran, and the German verwirren, meaning "to confuse", "to perplex", and "to bring into confusion".

History:

Main article: Military history

The earliest evidence of prehistoric warfare is a Mesolithic cemetery in Jebel Sahaba, which has been determined to be approximately 14,000 years old. About forty-five percent of the skeletons there displayed signs of violent death.

Since the rise of the state some 5,000 years ago, military activity has occurred over much of the globe. The advent of gunpowder and the acceleration of technological advances led to modern warfare. According to Conway W. Henderson, "One source claims that 14,500 wars have taken place between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, costing 3.5 billion lives, leaving only 300 years of peace (Beer 1981: 20)."

An unfavorable review of this estimate mentions the following regarding one of the proponents of this estimate: "In addition, perhaps feeling that the war casualties figure was improbably high, he changed 'approximately 3,640,000,000 human beings have been killed by war or the diseases produced by war' to 'approximately 1,240,000,000 human beings...&c.'"

The lower figure is more plausible, but could still be on the high side considering that the 100 deadliest acts of mass violence between 480 BC and 2002 AD (wars and other man-made disasters with at least 300,000 and up to 66 million victims) claimed about 455 million human lives in total.

Primitive warfare is estimated to have accounted for 15.1% of deaths and claimed 400 million victims. Added to the aforementioned figure of 1,240 million between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, this would mean a total of 1,640,000,000 people killed by war (including deaths from famine and disease caused by war) throughout the history and pre-history of mankind. For comparison, an estimated 1,680,000,000 people died from infectious diseases in the 20th century.

In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, says approximately 90–95% of known societies throughout history engaged in at least occasional warfare, and many fought constantly.

Keeley describes several styles of primitive combat such as small raids, large raids, and massacres. All of these forms of warfare were used by primitive societies, a finding supported by other researchers. Keeley explains that early war raids were not well organized, as the participants did not have any formal training. Scarcity of resources meant defensive works were not a cost-effective way to protect the society against enemy raids.

William Rubinstein wrote "Pre-literate societies, even those organised in a relatively advanced way, were renowned for their studied cruelty...'archaeology yields evidence of prehistoric massacres more severe than any recounted in ethnography [i.e., after the coming of the Europeans].'"

In Western Europe, since the late 18th century, more than 150 conflicts and about 600 battles have taken place. During the 20th century, war resulted in a dramatic intensification of the pace of social changes, and was a crucial catalyst for the emergence of the political Left as a force to be reckoned with.

In 1947, in view of the rapidly increasingly destructive consequences of modern warfare, and with a particular concern for the consequences and costs of the newly developed atom bomb, Albert Einstein famously stated, "I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones."

Mao Zedong urged the socialist camp not to fear nuclear war with the United States since, even if "half of mankind died, the other half would remain while imperialism would be razed to the ground and the whole world would become socialist."

A distinctive feature of war since 1945 is the absence of wars between major powers—indeed the near absence of any traditional wars between established countries. The major exceptions were the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the Iran–Iraq War 1980–1988, and the Gulf War of 1990–91. Instead, combat has largely been a matter of civil wars and insurgencies.

The Human Security Report 2005 documented a significant decline in the number and severity of armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s (see below). However, the evidence examined in the 2008 edition of the Center for International Development and Conflict Management's "Peace and Conflict" study indicated the overall decline in conflicts had stalled.

Types of warfare:

Main article: Types of war

- Asymmetric warfare is a conflict between belligerents of drastically different levels of military capability or size.

- Biological warfare, or germ warfare, is the use of weaponized biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- Chemical warfare involves the use of weaponized chemicals in combat. Poison gas as a chemical weapon was principally used during World War I, and resulted in over a million estimated casualties, including more than 100,000 civilians.

- Cold warfare is an intense international rivalry without direct military conflict, but with a sustained threat of it, including high levels of military preparations, expenditures, and development, and may involve active conflicts by indirect means, such as economic warfare, political warfare, covert operations, espionage, cyberwarfare, or proxy wars.

- Conventional warfare is declared war between states in which nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons are not used or see limited deployment.

- Cyberwarfare involves the actions by a nation-state or international organization to attack and attempt to damage another nation's information systems.

- Insurgency is a rebellion against authority, when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents (lawful combatants). An insurgency can be fought via counterinsurgency, and may also be opposed by measures to protect the population, and by political and economic actions of various kinds aimed at undermining the insurgents' claims against the incumbent regime.

- Information warfare is the application of destructive force on a large scale against information assets and systems, against the computers and networks that support the four critical infrastructures (the power grid, communications, financial, and transportation).

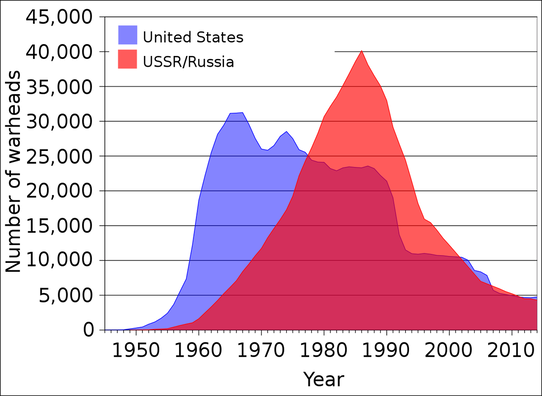

- Nuclear warfare is warfare in which nuclear weapons are the primary, or a major, method of achieving capitulation.

- Total war is warfare by any means possible, disregarding the laws of war, placing no limits on legitimate military targets, using weapons and tactics resulting in significant civilian casualties, or demanding a war effort requiring significant sacrifices by the friendly civilian population.

- Unconventional warfare, the opposite of conventional warfare, is an attempt to achieve military victory through acquiescence, capitulation, or clandestine support for one side of an existing conflict.

Aims:

Entities contemplating going to war and entities considering whether to end a war may formulate war aims as an evaluation/propaganda tool. War aims may stand as a proxy for national-military resolve.

Definition:

Fried defines war aims as "the desired territorial, economic, military or other benefits expected following successful conclusion of a war".

Classification:

Tangible/intangible aims:

- Tangible war aims may involve (for example) the acquisition of territory (as in the German goal of Lebensraum in the first half of the 20th century) or the recognition of economic concessions (as in the Anglo-Dutch Wars).

- Intangible war aims – like the accumulation of credibility or reputation – may have more tangible expression ("conquest restores prestige, annexation increases power").

Explicit/implicit aims:

- Explicit war aims may involve published policy decisions.

- Implicit war aims can take the form of minutes of discussion, memoranda and instructions.

Positive/negative aims:

- "Positive war aims" cover tangible outcomes.

- "Negative war aims" forestall or prevent undesired outcomes.

War aims can change in the course of conflict and may eventually morph into "peace conditions" – the minimal conditions under which a state may cease to wage a particular war.

Effects:

Main article: Effects of war

Military and civilian casualties in recent human history:

Throughout the course of human history, the average number of people dying from war has fluctuated relatively little, being about 1 to 10 people dying per 100,000. However, major wars over shorter periods have resulted in much higher casualty rates, with 100-200 casualties per 100,000 over a few years.

While conventional wisdom holds that casualties have increased in recent times due to technological improvements in warfare, this is not generally true. For instance, the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) had about the same number of casualties per capita as World War I, although it was higher during World War II (WWII). That said, overall the number of casualties from war has not significantly increased in recent times. Quite to the contrary, on a global scale the time since WWII has been unusually peaceful.

Largest by death toll:

Main articles:

The deadliest war in history, in terms of the cumulative number of deaths since its start, is World War II, from 1939 to 1945, with 60–85 million deaths, followed by the Mongol conquests at up to 60 million.

As concerns a belligerent's losses in proportion to its prewar population, the most destructive war in modern history may have been the Paraguayan War (see Paraguayan War casualties).

In 2013 war resulted in 31,000 deaths, down from 72,000 deaths in 1990. In 2003, Richard Smalley identified war as the sixth biggest problem (of ten) facing humanity for the next fifty years. War usually results in significant deterioration of infrastructure and the ecosystem, a decrease in social spending, famine, large-scale emigration from the war zone, and often the mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilians.

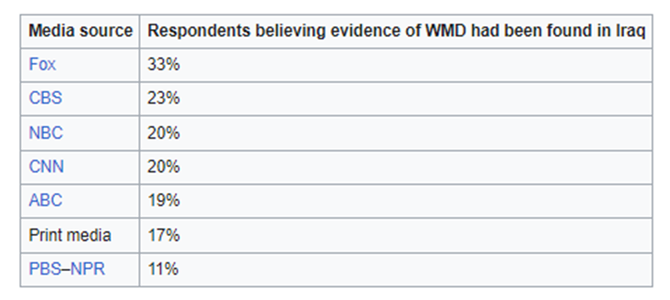

For instance, of the nine million people who were on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR in 1941, some 1.6 million were killed by the Germans in actions away from battlefields, including about 700,000 prisoners of war, 500,000 Jews, and 320,000 people counted as partisans (the vast majority of whom were unarmed civilians). Another byproduct of some wars is the prevalence of propaganda by some or all parties in the conflict, and increased revenues by weapons manufacturers.

Three of the ten most costly wars, in terms of loss of life, have been waged in the last century. These are the two World Wars, followed by the Second Sino-Japanese War (which is sometimes considered part of World War II, or as overlapping).

Most of the others involved China or neighboring peoples. The death toll of World War II, being over 60 million, surpasses all other war-death-tolls:

On military personnel:

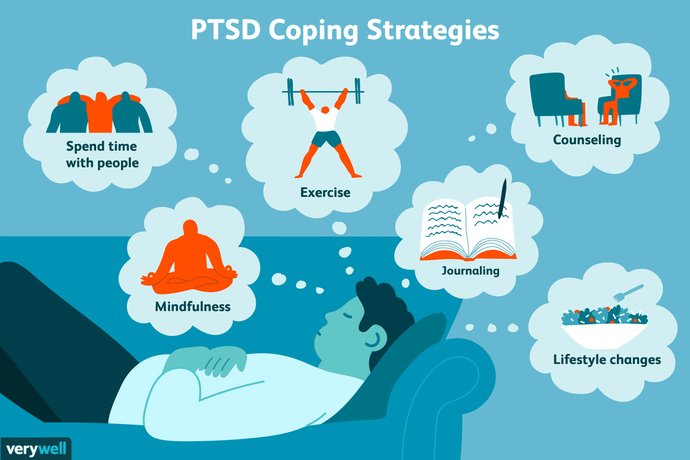

Military personnel subject to combat in war often suffer mental and physical injuries, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, disease, injury, and death.

In every war in which American soldiers have fought in, the chances of becoming a psychiatric casualty – of being debilitated for some period of time as a consequence of the stresses of military life – were greater than the chances of being killed by enemy fire.

— No More Heroes, Richard Gabriel

Swank and Marchand's World War II study found that after sixty days of continuous combat, 98% of all surviving military personnel will become psychiatric casualties. Psychiatric casualties manifest themselves in fatigue cases, confused states, conversion hysteria, anxiety, obsessional and compulsive states, and character disorders.

One-tenth of mobilized American men were hospitalized for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945, and after thirty-five days of uninterrupted combat, 98% of them manifested psychiatric disturbances in varying degrees.

— 14–18: Understanding the Great War, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Annette Becker.

Additionally, it has been estimated anywhere from 18% to 54% of Vietnam war veterans suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder.

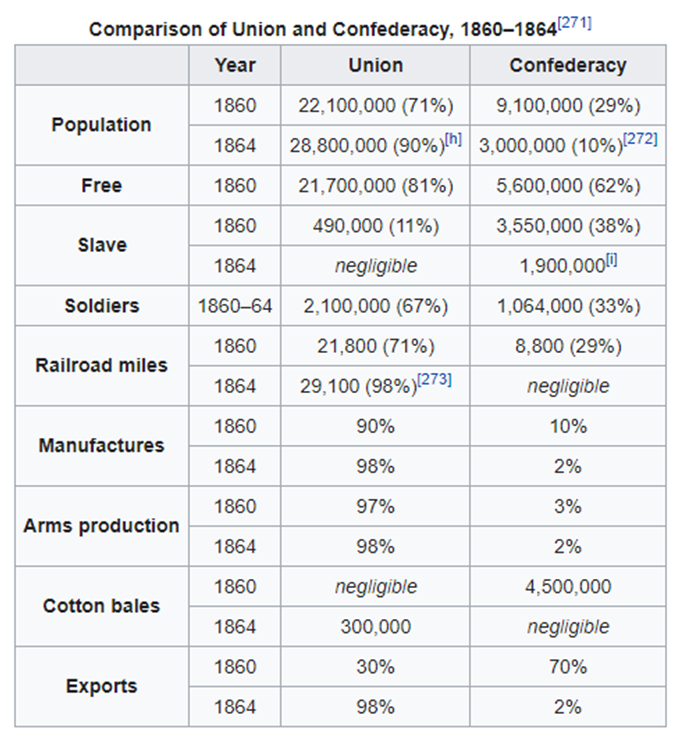

Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white American males aged 13 to 43 died in the American Civil War, including about 6% in the North and approximately 18% in the South.

The war remains the deadliest conflict in American history, resulting in the deaths of 620,000 military personnel. United States military casualties of war since 1775 have totaled over two million. Of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilized in World War I, 8 million were killed, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured.

During Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of typhus than were killed by the Russians. Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, less than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500 to 1914 by typhus than from military action.

In addition, if it were not for modern medical advances there would be thousands more dead from disease and infection. For instance, during the Seven Years' War, the Royal Navy reported it conscripted 184,899 sailors, of whom 133,708 (72%) died of disease or were 'missing'.

It is estimated that between 1985 and 1994, 378,000 people per year died due to war.

On civilians:

See also: Civilian casualties

Most wars have resulted in significant loss of life, along with destruction of infrastructure and resources (which may lead to famine, disease, and death in the civilian population).

During the Thirty Years' War in Europe, the population of the Holy Roman Empire was reduced by 15 to 40 percent. Civilians in war zones may also be subject to war atrocities such as genocide, while survivors may suffer the psychological aftereffects of witnessing the destruction of war.

War also results in lower quality of life and worse health outcomes. A medium-sized conflict with about 2,500 battle deaths reduces civilian life expectancy by one year and increases infant mortality by 10% and malnutrition by 3.3%. Additionally, about 1.8% of the population loses access to drinking water.

Most estimates of World War II casualties indicate around 60 million people died, 40 million of whom were civilians. Deaths in the Soviet Union were around 27 million. Since a high proportion of those killed were young men who had not yet fathered any children, population growth in the postwar Soviet Union was much lower than it otherwise would have been.

Economic:

See also: Military Keynesianism

Once a war has ended, losing nations are sometimes required to pay war reparations to the victorious nations. In certain cases, land is ceded to the victorious nations. For example, the territory of Alsace-Lorraine has been traded between France and Germany on three different occasions.

Typically, war becomes intertwined with the economy and many wars are partially or entirely based on economic reasons.

Some economists believe war can stimulate a country's economy (high government spending for World War II is often credited with bringing the U.S. out of the Great Depression by most Keynesian economists), but in many cases, such as the wars of Louis XIV, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War I, warfare primarily results in damage to the economy of the countries involved.

For example, Russia's involvement in World War I took such a toll on the Russian economy that it almost collapsed and greatly contributed to the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

World War II:

World War II was the most financially costly conflict in history; its belligerents cumulatively spent about a trillion U.S. dollars on the war effort (as adjusted to 1940 prices). The Great Depression of the 1930s ended as nations increased their production of war materials.

By the end of the war, 70% of European industrial infrastructure was destroyed. Property damage in the Soviet Union inflicted by the Axis invasion was estimated at a value of 679 billion rubles.

The combined damage consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, 2,508 church buildings, 31,850 industrial establishments, 40,000 mi (64,374 km) of railroad, 4100 railroad stations, 40,000 hospitals, 84,000 schools, and 43,000 public libraries.

Theories of motivation:

Main article: International relations theory

There are many theories about the motivations for war, but no consensus about which are most common. Carl von Clausewitz said, 'Every age has its own kind of war, its own limiting conditions, and its own peculiar preconceptions.'

Psychoanalytic:

Dutch psychoanalyst Joost Meerloo held that, "War is often...a mass discharge of accumulated internal rage (where)...the inner fears of mankind are discharged in mass destruction."

Other psychoanalysts such as E.F.M. Durban and John Bowlby have argued human beings are inherently violent. This aggressiveness is fueled by displacement and projection where a person transfers his or her grievances into bias and hatred against other races, religions, nations or ideologies. By this theory, the nation state preserves order in the local society while creating an outlet for aggression through warfare.

The Italian psychoanalyst Franco Fornari, a follower of Melanie Klein, thought war was the paranoid or projective "elaboration" of mourning. Fornari thought war and violence develop out of our "love need": our wish to preserve and defend the sacred object to which we are attached, namely our early mother and our fusion with her.

For the adult, nations are the sacred objects that generate warfare. Fornari focused upon sacrifice as the essence of war: the astonishing willingness of human beings to die for their country, to give over their bodies to their nation.

Despite Fornari's theory that man's altruistic desire for self-sacrifice for a noble cause is a contributing factor towards war, few wars have originated from a desire for war among the general populace. Far more often the general population has been reluctantly drawn into war by its rulers.

One psychological theory that looks at the leaders is advanced by Maurice Walsh. He argues the general populace is more neutral towards war and wars occur when leaders with a psychologically abnormal disregard for human life are placed into power. War is caused by leaders who seek war such as Napoleon and Hitler. Such leaders most often come to power in times of crisis when the populace opts for a decisive leader, who then leads the nation to war.

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. ... the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders.

"That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country." -- Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trials, 18 April 1946.

Evolutionary:

See also: Prehistoric warfare

Several theories concern the evolutionary origins of warfare. There are two main schools:

The latter school argues that since warlike behavior patterns are found in many primate species such as chimpanzees, as well as in many ant species, group conflict may be a general feature of animal social behavior. Some proponents of the idea argue that war, while innate, has been intensified greatly by developments of technology and social organization such as weaponry and states.

Psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker argued that war-related behaviors may have been naturally selected in the ancestral environment due to the benefits of victory. He also argued that in order to have credible deterrence against other groups (as well as on an individual level), it was important to have a reputation for retaliation, causing humans to develop instincts for revenge as well as for protecting a group's (or an individual's) reputation ("honor").

Crofoot and Wrangham have argued that warfare, if defined as group interactions in which "coalitions attempt to aggressively dominate or kill members of other groups", is a characteristic of most human societies. Those in which it has been lacking "tend to be societies that were politically dominated by their neighbors".

Ashley Montagu strongly denied universalistic instinctual arguments, arguing that social factors and childhood socialization are important in determining the nature and presence of warfare. Thus, he argues, warfare is not a universal human occurrence and appears to have been a historical invention, associated with certain types of human societies.

Montagu's argument is supported by ethnographic research conducted in societies where the concept of aggression seems to be entirely absent, e.g. the Chewong and Semai of the Malay peninsula. Bobbi S. Low has observed correlation between warfare and education, noting societies where warfare is commonplace encourage their children to be more aggressive.

Economic:

See also: Resource war

War can be seen as a growth of economic competition in a competitive international system. In this view wars begin as a pursuit of markets for natural resources and for wealth. War has also been linked to economic development by economic historians and development economists studying state-building and fiscal capacity.

While this theory has been applied to many conflicts, such counter arguments become less valid as the increasing mobility of capital and information level the distributions of wealth worldwide, or when considering that it is relative, not absolute, wealth differences that may fuel wars.

There are those on the extreme right of the political spectrum who provide support, fascists in particular, by asserting a natural right of a strong nation to whatever the weak cannot hold by force. Some centrist, capitalist, world leaders, including Presidents of the United States and U.S. Generals, expressed support for an economic view of war.

Marxist:

Main article: Marxist explanations of warfare

The Marxist theory of war is quasi-economic in that it states all modern wars are caused by competition for resources and markets between great (imperialist) powers, claiming these wars are a natural result of capitalism.

Marxist economists Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin theorized that imperialism was the result of capitalist countries needing new markets. Expansion of the means of production is only possible if there is a corresponding growth in consumer demand.

Since the workers in a capitalist economy would be unable to fill the demand, producers must expand into non-capitalist markets to find consumers for their goods, hence driving imperialism.

Demographic:

Demographic theories can be grouped into two classes, Malthusian and youth bulge theories:

Malthusian theories see expanding population and scarce resources as a source of violent conflict. Pope Urban II in 1095, on the eve of the First Crusade, advocating Crusade as a solution to European overpopulation, said:

For this land which you now inhabit, shut in on all sides by the sea and the mountain peaks, is too narrow for your large population; it scarcely furnishes food enough for its cultivators. Hence it is that you murder and devour one another, that you wage wars, and that many among you perish in civil strife. Let hatred, therefore, depart from among you; let your quarrels end. Enter upon the road to the Holy Sepulchre; wrest that land from a wicked race, and subject it to yourselves.

This is one of the earliest expressions of what has come to be called the Malthusian theory of war, in which wars are caused by expanding populations and limited resources. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) wrote that populations always increase until they are limited by war, disease, or famine.

The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan and other countries in the Sahel region have been exacerbated by land degradation and population growth.

Youth bulge theories: According to Heinsohn, who proposed youth bulge theory in its most generalized form, a youth bulge occurs when 30 to 40 percent of the males of a nation belong to the "fighting age" cohorts from 15 to 29 years of age. It will follow periods with total fertility rates as high as 4–8 children per woman with a 15–29-year delay.

Heinsohn saw both past "Christianist" European colonialism and imperialism, as well as today's Islamist civil unrest and terrorism as results of high birth rates producing youth bulges.

Among prominent historical events that have been attributed to youth bulges are the role played by the historically large youth cohorts in the rebellion and revolution waves of early modern Europe, including the French Revolution of 1789, and the effect of economic depression upon the largest German youth cohorts ever in explaining the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s. The 1994 Rwandan genocide has also been analyzed as following a massive youth bulge.

Youth bulge theory has been subjected to statistical analysis by the World Bank, Population Action International, and the Berlin Institute for Population and Development. Youth bulge theories have been criticized as leading to racial, gender and age discrimination.

Cultural:

Geoffrey Parker argues that what distinguishes the "Western way of war" based in Western Europe chiefly allows historians to explain its extraordinary success in conquering most of the world after 1500:

The Western way of war rests upon five principal foundations: technology, discipline, a highly aggressive military tradition, a remarkable capacity to innovate and to respond rapidly to the innovation of others and—from about 1500 onward—a unique system of war finance.

The combination of all five provided a formula for military success....The outcome of wars has been determined less by technology, then by better war plans, the achievement of surprise, greater economic strength, and above all superior discipline.

Parker argues that Western armies were stronger because they emphasized discipline, that is, "the ability of a formation to stand fast in the face of the enemy, where they're attacking or being attacked, without giving way to the natural impulse of fear and panic." Discipline came from drills and marching in formation, target practice, and creating small "artificial kinship groups: such as the company and the platoon, to enhance psychological cohesion and combat efficiency.

Rationalist:

Rationalism is an international relations theory or framework. Rationalism (and Neorealism (international relations)) operate under the assumption that states or international actors are rational, seek the best possible outcomes for themselves, and desire to avoid the costs of war.

Under one game theory approach, rationalist theories posit all actors can bargain, would be better off if war did not occur, and likewise seek to understand why war nonetheless reoccurs. Under another rationalist game theory without bargaining, the peace war game, optimal strategies can still be found that depend upon number of iterations played.

In "Rationalist Explanations for War", James Fearon examined three rationalist explanations for why some countries engage in war:

"Information asymmetry with incentives to misrepresent" occurs when two countries have secrets about their individual capabilities, and do not agree on either: who would win a war between them, or the magnitude of state's victory or loss.

For instance, Geoffrey Blainey argues that war is a result of miscalculation of strength. He cites historical examples of war and demonstrates, "war is usually the outcome of a diplomatic crisis which cannot be solved because both sides have conflicting estimates of their bargaining power." Thirdly, bargaining may fail due to the states' inability to make credible commitments.

Within the rationalist tradition, some theorists have suggested that individuals engaged in war suffer a normal level of cognitive bias, but are still "as rational as you and me".

According to philosopher Iain King, "Most instigators of conflict overrate their chances of success, while most participants underrate their chances of injury...." King asserts that "Most catastrophic military decisions are rooted in GroupThink" which is faulty, but still rational.

The rationalist theory focused around bargaining is currently under debate. The Iraq War proved to be an anomaly that undercuts the validity of applying rationalist theory to some wars.

Political science:

The statistical analysis of war was pioneered by Lewis Fry Richardson following World War I. More recent databases of wars and armed conflict have been assembled by the Correlates of War Project, Peter Brecke and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program.

The following subsections consider causes of war from system, societal, and individual levels of analysis. This kind of division was first proposed by Kenneth Waltz in Man, the State, and War and has been often used by political scientists since then.

System-level: There are several different international relations theory schools. Supporters of realism in international relations argue that the motivation of states is the quest for security, and conflicts can arise from the inability to distinguish defense from offense, which is called the security dilemma.

Within the realist school as represented by scholars such as Henry Kissinger and Hans Morgenthau, and the neorealist school represented by scholars such as Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer, two main sub-theories are:

The two theories are not mutually exclusive and may be used to explain disparate events according to the circumstance.

Liberalism as it relates to international relations emphasizes factors such as trade, and its role in disincentivizing conflict which will damage economic relations.

Realists respond that military force may sometimes be at least as effective as trade at achieving economic benefits, especially historically if not as much today.

Furthermore, trade relations which result in a high level of dependency may escalate tensions and lead to conflict. Empirical data on the relationship of trade to peace are mixed, and moreover, some evidence suggests countries at war don't necessarily trade less with each other.

Societal-level:

Individual-level:

These theories suggest differences in people's personalities, decision-making, emotions, belief systems, and biases are important in determining whether conflicts get out of hand. For instance, it has been proposed that conflict is modulated by bounded rationality and various cognitive biases, such as prospect theory.

Ethics:

The morality of war has been the subject of debate for thousands of years.

The two principal aspects of ethics in war, according to the just war theory, are jus ad bellum and jus in bello.

Jus ad bellum (right to war), dictates which unfriendly acts and circumstances justify a proper authority in declaring war on another nation. There are six main criteria for the declaration of a just war:

Jus in bello (right in war), is the set of ethical rules when conducting war. The two main principles are proportionality and discrimination. Proportionality regards how much force is necessary and morally appropriate to the ends being sought and the injustice suffered.

The principle of discrimination determines who are the legitimate targets in a war, and specifically makes a separation between combatants, who it is permissible to kill, and non-combatants, who it is not. Failure to follow these rules can result in the loss of legitimacy for the just-war-belligerent.

The just war theory was foundational in the creation of the United Nations and in international law's regulations on legitimate war.

Fascism, and the ideals it encompasses, such as Pragmatism, racism, and social Darwinism, hold that violence is good.

Pragmatism holds that war and violence can be good if it serves the ends of the people, without regard for universal morality.

Racism holds that violence is good so that a master race can be established, or to purge an inferior race from the earth, or both.

Social Darwinism asserts that violence is sometimes necessary to weed the unfit from society so civilization can flourish.

These are broad archetypes for the general position that the ends justify the means. Lewis Coser, U.S. conflict theorist and sociologist, argued conflict provides a function and a process whereby a succession of new equilibriums are created. Thus, the struggle of opposing forces, rather than being disruptive, may be a means of balancing and maintaining a social structure or society.

Limiting and stopping:

Main article: Anti-war movement

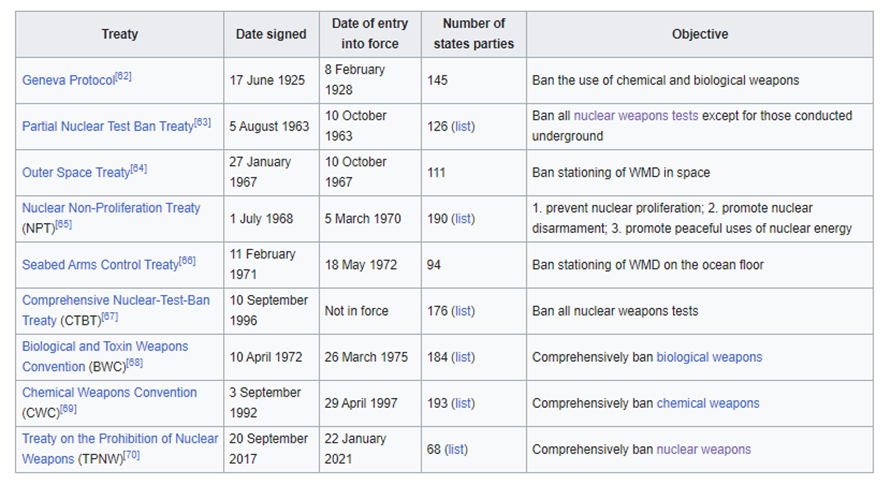

Religious groups have long formally opposed or sought to limit war as in the Second Vatican Council document Gaudiem et Spes: "Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation."

Anti-war movements have existed for every major war in the 20th century, including, most prominently, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War.

In the 21st century, worldwide anti-war movements occurred in response to the United States invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Protests opposing the War in Afghanistan occurred in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Pauses:

During a war, brief pauses of violence may be called for, and further agreed to— ceasefire, temporary cessation, humanitarian pauses and corridors, days of tranquility, de-confliction arrangements.

There a number of disadvantages, obstacles and hesitations against implementing such pauses such as a humanitarian corridor.

Pauses in conflict are also ill-advised; reasons such as "delay of defeat" and the "weakening of credibility". Natural causes for a pause may include events such as the 2019 coronavirus pandemic.

See also

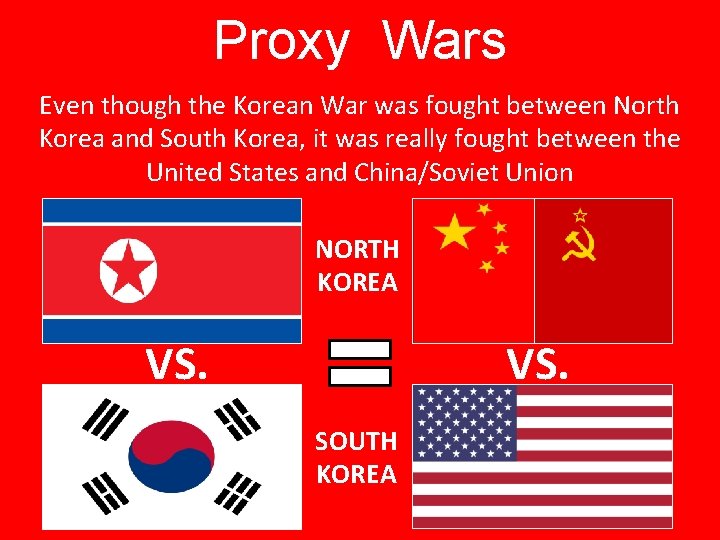

Proxy War:

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors which act on the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities.

In order for a conflict to be considered a proxy war, there must be a direct, long-term relationship between external actors and the belligerents involved. The aforementioned relationship usually takes the form of funding, military training, arms, or other forms of material assistance which assist a belligerent party in sustaining its war effort.

History:

During classical antiquity and the Middle Ages, many non-state proxies were external parties that were introduced to an internal conflict and aligned themselves with a belligerent to gain influence and to further their own interests in the region.

Proxies could be introduced by an external or local power and most commonly took the form of irregular armies which were used to achieve their sponsor's goals in a contested region.

Some medieval states like the Byzantine Empire used proxy warfare as a foreign policy tool by deliberately cultivating intrigue among hostile rivals and then backing them when they went to war with each other.

Other states regarded proxy wars as merely a useful extension of a pre-existing conflict, such as France and England during the Hundred Years' War, both of which initiated a longstanding practice of supporting privateers, which targeted the other's merchant shipping. France used England's turmoil of the Wars of the Roses from their victory as a proxy against the Burgundian State.

The Ottoman Empire likewise used the Barbary pirates as proxies to harass Western European powers in the Mediterranean Sea.

Frequent application of the term "proxy war" indicates its prominent place in academic researches on international relations. Separate implementation of soft power and hard power proved to be unsuccessful in recent years. Accordingly, great failures in classic wars increased tendencies towards proxy wars.

Since the early 20th century, proxy wars have most commonly taken the form of states assuming the role of sponsors to non-state proxies and essentially using them as fifth columns to undermine adversarial powers.

That type of proxy warfare includes external support for a faction engaged in a civil war, terrorists, national liberation movements, and insurgent groups, or assistance to a national revolt against foreign occupation.

For example, the British government partially organized and instigated the Arab Revolt to undermine the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. Many proxy wars began assuming a distinctive ideological dimension after the Spanish Civil War, which pitted the fascist political ideology of Italy and National Socialist ideology of Nazi Germany against the communist ideology of the Soviet Union without involving these states in open warfare with each other.

Sponsors of both sides also used the Spanish conflict as a proving ground for their own weapons and battlefield tactics.

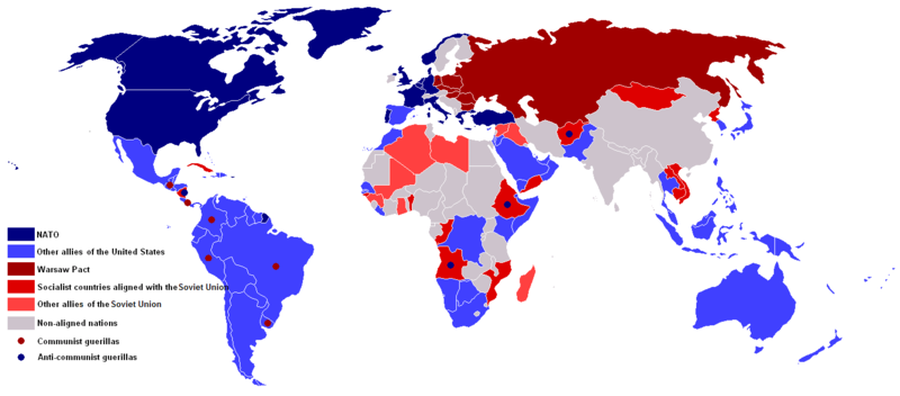

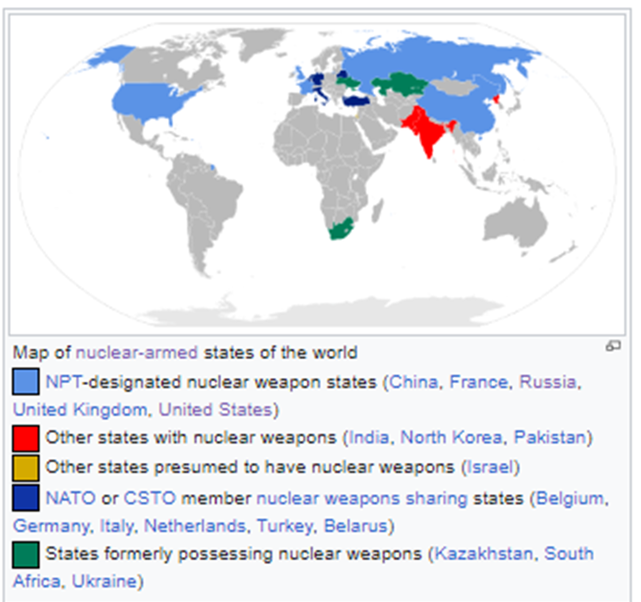

During the Cold War, proxy warfare was motivated by fears that a conventional war between the United States and the Soviet Union would result in nuclear holocaust, which rendered the use of ideological proxies a safer way of exercising hostilities.

The Soviet government found that supporting parties antagonistic to Americans and other Western nations to be a cost-effective way to combat NATO's influence, compared to direct military engagement.

Besides, the proliferation of televised media and its impact on public perception made the US public especially susceptible to war-weariness and skeptical of risking life abroad. That encouraged the American practice of arming insurgent forces, such as the funneling of supplies to the mujahideen during the Soviet–Afghan War.

Other examples of proxy war are Korea War and Vietnam War.

Abstract:

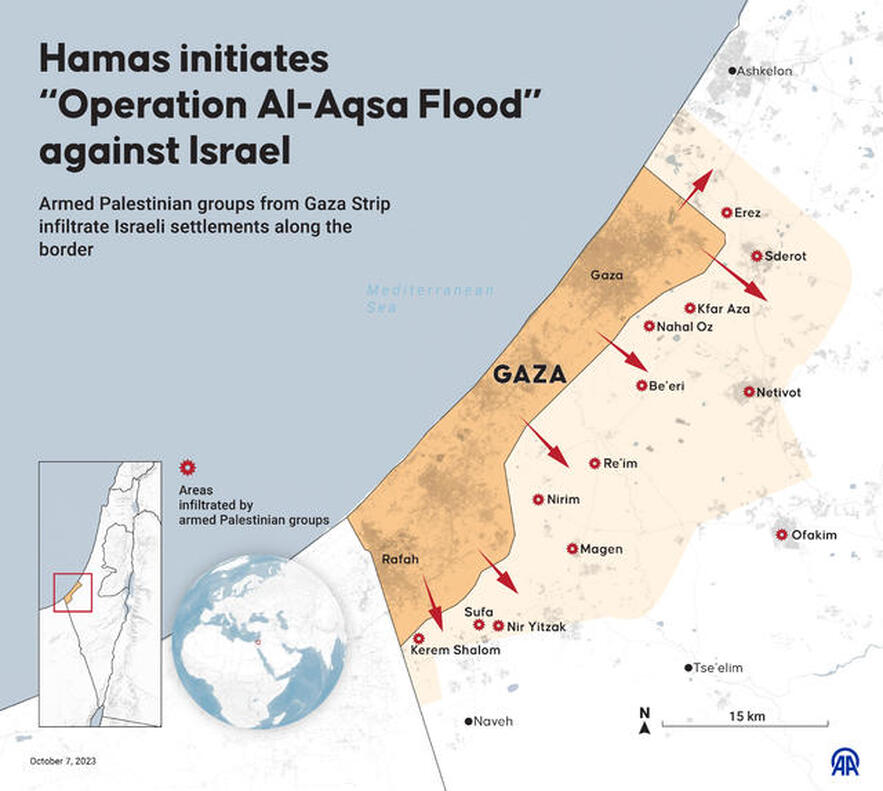

A significant disparity in the belligerents' conventional military strength may motivate the weaker party to begin or continue a conflict through allied nations or non-state actors. Such a situation arose during the Arab–Israeli conflict, which continued as a series of proxy wars following Israel's decisive defeat of the Arab coalitions in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War.

The coalition members, upon their failure to achieve military dominance via direct conventional warfare, have since resorted to funding armed insurgent and paramilitary organizations, such as Hezbollah, to engage in irregular combat against Israel.

The Iran–Israel proxy conflict involves threats and hostility by Iran's leaders against Israel.

Additionally, the governments of some nations, particularly liberal democracies, may choose to engage in proxy warfare (despite their military superiority) if most of their citizens oppose declaring or entering a conventional war.

That featured prominently in US strategy following the Vietnam War because of the so-called "Vietnam Syndrome" of extreme war weariness among the American population.

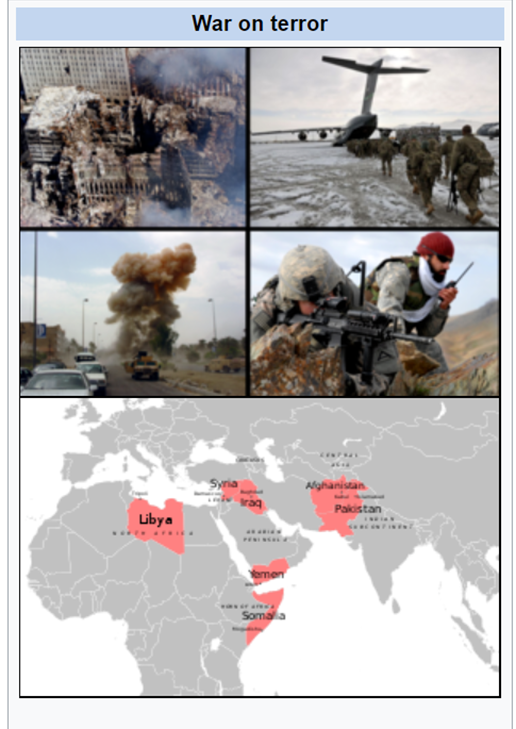

That was also a significant factor in motivating the US to enter conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War by proxy actors after a series of costly drawn-out direct engagements in the Middle East spurred a recurrence of war weariness, the "War on Terror syndrome."

Nations may also resort to proxy warfare to avoid potential negative international reactions from allied nations, profitable trading partners, or intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations. That is especially significant when standing peace treaties, acts of the alliance or other international agreements ostensibly forbid direct warfare.

Breaking such agreements could lead to a variety of negative consequences due to either negative international reaction (see above), punitive provisions listed in the prior agreement, or retaliatory action by the other parties and their allies.

In some cases, nations may be motivated to engage in proxy warfare because of financial concerns: supporting irregular troops, insurgents, non-state actors, or less-advanced allied militaries (often with obsolete or surplus equipment) can be significantly cheaper than deploying national armed forces, and the proxies usually bear the brunt of casualties and economic damage resulting from prolonged conflict.

Another common motivating factor is the existence of a security dilemma. A nation may use military intervention to install a more favorable government in a third-party state. Rival nations may perceive the intervention as a weakened position to their own security and may respond by attempting to undermine such efforts, often by backing parties favorable to their own interests (such as those directly or indirectly under their control, sympathetic to their cause, or ideologically aligned).

In that case, if one or both rivals come to believe that their favored faction is at a disadvantage, they will often respond by escalating military and/or financial support.

If their counterpart(s), perceiving a material threat or desiring to avoid the appearance of weakness or defeat, follow suit, a proxy war ensues between the two powers. That was a major factor in many of the proxy wars during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as in the ongoing series of conflicts between Saudi Arabia and Iran, especially in Yemen and Syria.

Effects:

Proxy wars can have a huge impact, especially on the local area. A proxy war with significant effects occurred between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Vietnam War.

In particular, the bombing campaign Operation Rolling Thunder destroyed significant amounts of infrastructure, making life more difficult for the North Vietnamese.

Also, unexploded bombs dropped during the campaign have killed tens of thousands since the war ended not only in Vietnam but also in Cambodia and Laos.

Also significant was the Soviet–Afghan War (see Operation Cyclone), which cost thousands of lives and billions of dollars, bankrupting the Soviet Union and contributing to its collapse.

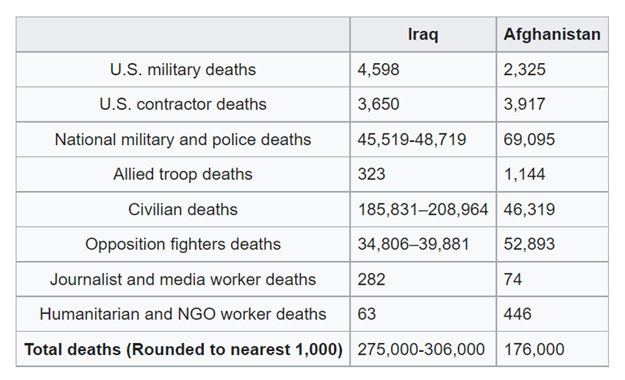

The conflict in the Middle East between Saudi Arabia and Iran is another example of the destructive impact of proxy wars. The conflict, in conjunction with US-led invasions and interventions as part of the War on Terror, has contributed to, among other things, the Syrian Civil War, the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the current civil war in Yemen, and the re-emergence of the Taliban.

Since 2003, nearly 500,000 have died in Iraq. Since 2011, more than 500,000 have died in Syria. In Yemen, over 1,000 have died in just one month. In Afghanistan, more than 17,000 have been killed since 2009. In Pakistan, more than 57,000 have been killed since 2003.

In general, lengths, intensities, and scales of armed conflicts are often greatly increased if belligerents' capabilities are augmented by external support. Belligerents are often less likely to engage in diplomatic negotiations, peace talks are less likely to bear fruit, and damage to infrastructure can be many times greater.

See also:

Military personnel subject to combat in war often suffer mental and physical injuries, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, disease, injury, and death.

In every war in which American soldiers have fought in, the chances of becoming a psychiatric casualty – of being debilitated for some period of time as a consequence of the stresses of military life – were greater than the chances of being killed by enemy fire.

— No More Heroes, Richard Gabriel

Swank and Marchand's World War II study found that after sixty days of continuous combat, 98% of all surviving military personnel will become psychiatric casualties. Psychiatric casualties manifest themselves in fatigue cases, confused states, conversion hysteria, anxiety, obsessional and compulsive states, and character disorders.

One-tenth of mobilized American men were hospitalized for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945, and after thirty-five days of uninterrupted combat, 98% of them manifested psychiatric disturbances in varying degrees.

— 14–18: Understanding the Great War, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Annette Becker.

Additionally, it has been estimated anywhere from 18% to 54% of Vietnam war veterans suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder.

Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white American males aged 13 to 43 died in the American Civil War, including about 6% in the North and approximately 18% in the South.

The war remains the deadliest conflict in American history, resulting in the deaths of 620,000 military personnel. United States military casualties of war since 1775 have totaled over two million. Of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilized in World War I, 8 million were killed, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured.

During Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of typhus than were killed by the Russians. Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, less than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500 to 1914 by typhus than from military action.

In addition, if it were not for modern medical advances there would be thousands more dead from disease and infection. For instance, during the Seven Years' War, the Royal Navy reported it conscripted 184,899 sailors, of whom 133,708 (72%) died of disease or were 'missing'.

It is estimated that between 1985 and 1994, 378,000 people per year died due to war.

On civilians:

See also: Civilian casualties

Most wars have resulted in significant loss of life, along with destruction of infrastructure and resources (which may lead to famine, disease, and death in the civilian population).

During the Thirty Years' War in Europe, the population of the Holy Roman Empire was reduced by 15 to 40 percent. Civilians in war zones may also be subject to war atrocities such as genocide, while survivors may suffer the psychological aftereffects of witnessing the destruction of war.

War also results in lower quality of life and worse health outcomes. A medium-sized conflict with about 2,500 battle deaths reduces civilian life expectancy by one year and increases infant mortality by 10% and malnutrition by 3.3%. Additionally, about 1.8% of the population loses access to drinking water.

Most estimates of World War II casualties indicate around 60 million people died, 40 million of whom were civilians. Deaths in the Soviet Union were around 27 million. Since a high proportion of those killed were young men who had not yet fathered any children, population growth in the postwar Soviet Union was much lower than it otherwise would have been.

Economic:

See also: Military Keynesianism

Once a war has ended, losing nations are sometimes required to pay war reparations to the victorious nations. In certain cases, land is ceded to the victorious nations. For example, the territory of Alsace-Lorraine has been traded between France and Germany on three different occasions.

Typically, war becomes intertwined with the economy and many wars are partially or entirely based on economic reasons.

Some economists believe war can stimulate a country's economy (high government spending for World War II is often credited with bringing the U.S. out of the Great Depression by most Keynesian economists), but in many cases, such as the wars of Louis XIV, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War I, warfare primarily results in damage to the economy of the countries involved.

For example, Russia's involvement in World War I took such a toll on the Russian economy that it almost collapsed and greatly contributed to the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

World War II:

World War II was the most financially costly conflict in history; its belligerents cumulatively spent about a trillion U.S. dollars on the war effort (as adjusted to 1940 prices). The Great Depression of the 1930s ended as nations increased their production of war materials.

By the end of the war, 70% of European industrial infrastructure was destroyed. Property damage in the Soviet Union inflicted by the Axis invasion was estimated at a value of 679 billion rubles.

The combined damage consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, 2,508 church buildings, 31,850 industrial establishments, 40,000 mi (64,374 km) of railroad, 4100 railroad stations, 40,000 hospitals, 84,000 schools, and 43,000 public libraries.

Theories of motivation:

Main article: International relations theory

There are many theories about the motivations for war, but no consensus about which are most common. Carl von Clausewitz said, 'Every age has its own kind of war, its own limiting conditions, and its own peculiar preconceptions.'

Psychoanalytic:

Dutch psychoanalyst Joost Meerloo held that, "War is often...a mass discharge of accumulated internal rage (where)...the inner fears of mankind are discharged in mass destruction."

Other psychoanalysts such as E.F.M. Durban and John Bowlby have argued human beings are inherently violent. This aggressiveness is fueled by displacement and projection where a person transfers his or her grievances into bias and hatred against other races, religions, nations or ideologies. By this theory, the nation state preserves order in the local society while creating an outlet for aggression through warfare.

The Italian psychoanalyst Franco Fornari, a follower of Melanie Klein, thought war was the paranoid or projective "elaboration" of mourning. Fornari thought war and violence develop out of our "love need": our wish to preserve and defend the sacred object to which we are attached, namely our early mother and our fusion with her.

For the adult, nations are the sacred objects that generate warfare. Fornari focused upon sacrifice as the essence of war: the astonishing willingness of human beings to die for their country, to give over their bodies to their nation.

Despite Fornari's theory that man's altruistic desire for self-sacrifice for a noble cause is a contributing factor towards war, few wars have originated from a desire for war among the general populace. Far more often the general population has been reluctantly drawn into war by its rulers.

One psychological theory that looks at the leaders is advanced by Maurice Walsh. He argues the general populace is more neutral towards war and wars occur when leaders with a psychologically abnormal disregard for human life are placed into power. War is caused by leaders who seek war such as Napoleon and Hitler. Such leaders most often come to power in times of crisis when the populace opts for a decisive leader, who then leads the nation to war.

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. ... the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders.

"That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country." -- Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trials, 18 April 1946.

Evolutionary:

See also: Prehistoric warfare

Several theories concern the evolutionary origins of warfare. There are two main schools:

- One sees organized warfare as emerging in or after the Mesolithic as a result of complex social organization and greater population density and competition over resources;

- the other sees human warfare as a more ancient practice derived from common animal tendencies, such as territoriality and sexual competition.

The latter school argues that since warlike behavior patterns are found in many primate species such as chimpanzees, as well as in many ant species, group conflict may be a general feature of animal social behavior. Some proponents of the idea argue that war, while innate, has been intensified greatly by developments of technology and social organization such as weaponry and states.

Psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker argued that war-related behaviors may have been naturally selected in the ancestral environment due to the benefits of victory. He also argued that in order to have credible deterrence against other groups (as well as on an individual level), it was important to have a reputation for retaliation, causing humans to develop instincts for revenge as well as for protecting a group's (or an individual's) reputation ("honor").

Crofoot and Wrangham have argued that warfare, if defined as group interactions in which "coalitions attempt to aggressively dominate or kill members of other groups", is a characteristic of most human societies. Those in which it has been lacking "tend to be societies that were politically dominated by their neighbors".

Ashley Montagu strongly denied universalistic instinctual arguments, arguing that social factors and childhood socialization are important in determining the nature and presence of warfare. Thus, he argues, warfare is not a universal human occurrence and appears to have been a historical invention, associated with certain types of human societies.

Montagu's argument is supported by ethnographic research conducted in societies where the concept of aggression seems to be entirely absent, e.g. the Chewong and Semai of the Malay peninsula. Bobbi S. Low has observed correlation between warfare and education, noting societies where warfare is commonplace encourage their children to be more aggressive.

Economic:

See also: Resource war

War can be seen as a growth of economic competition in a competitive international system. In this view wars begin as a pursuit of markets for natural resources and for wealth. War has also been linked to economic development by economic historians and development economists studying state-building and fiscal capacity.

While this theory has been applied to many conflicts, such counter arguments become less valid as the increasing mobility of capital and information level the distributions of wealth worldwide, or when considering that it is relative, not absolute, wealth differences that may fuel wars.

There are those on the extreme right of the political spectrum who provide support, fascists in particular, by asserting a natural right of a strong nation to whatever the weak cannot hold by force. Some centrist, capitalist, world leaders, including Presidents of the United States and U.S. Generals, expressed support for an economic view of war.

Marxist:

Main article: Marxist explanations of warfare

The Marxist theory of war is quasi-economic in that it states all modern wars are caused by competition for resources and markets between great (imperialist) powers, claiming these wars are a natural result of capitalism.

Marxist economists Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin theorized that imperialism was the result of capitalist countries needing new markets. Expansion of the means of production is only possible if there is a corresponding growth in consumer demand.

Since the workers in a capitalist economy would be unable to fill the demand, producers must expand into non-capitalist markets to find consumers for their goods, hence driving imperialism.

Demographic:

Demographic theories can be grouped into two classes, Malthusian and youth bulge theories:

Malthusian theories see expanding population and scarce resources as a source of violent conflict. Pope Urban II in 1095, on the eve of the First Crusade, advocating Crusade as a solution to European overpopulation, said:

For this land which you now inhabit, shut in on all sides by the sea and the mountain peaks, is too narrow for your large population; it scarcely furnishes food enough for its cultivators. Hence it is that you murder and devour one another, that you wage wars, and that many among you perish in civil strife. Let hatred, therefore, depart from among you; let your quarrels end. Enter upon the road to the Holy Sepulchre; wrest that land from a wicked race, and subject it to yourselves.

This is one of the earliest expressions of what has come to be called the Malthusian theory of war, in which wars are caused by expanding populations and limited resources. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) wrote that populations always increase until they are limited by war, disease, or famine.

The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan and other countries in the Sahel region have been exacerbated by land degradation and population growth.