Copyright © 2015 Bert N. Langford (Images may be subject to copyright. Please send feedback)

Welcome to Our Generation USA!

Social Equality

addresses the successes and failures of achieving complete Equality between Americans, regardless of politics, race, gender or creed, age, economic circumstances, religion, disabilities, and including all minorities

See also:

Humanitarians

Feminism

Great Americans

Culture

Law & Order

Politics

Worst of Humanity

Social Equality vs. Social Inequality including a List of Countries by Income Equality and by Distribution of Wealth

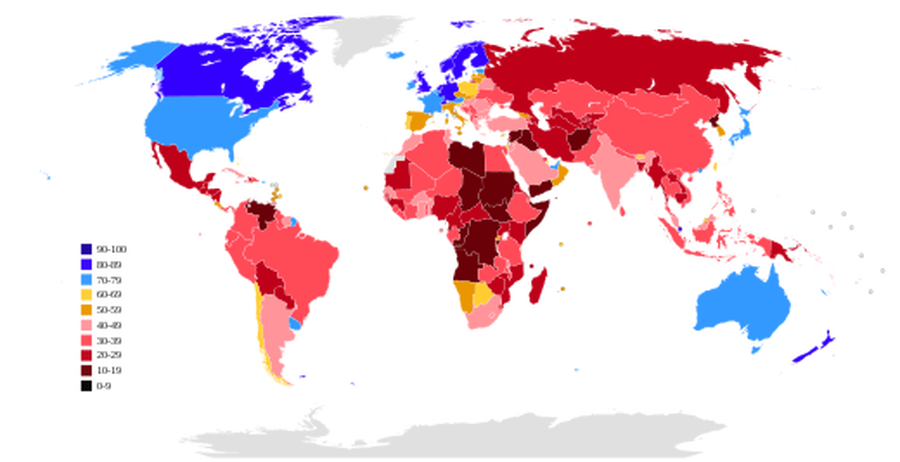

- Click here for a List of Countries by Income Equality

- Click here for a List of Countries by distribution of wealth

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific society or isolated group have the same status in certain respects, including civil rights, freedom of speech, property rights and equal access to certain social goods and social services.

However, it also includes concepts of health equality, economic equality and other social securities. It also includes equal opportunities and obligations, and so involves the whole of society.

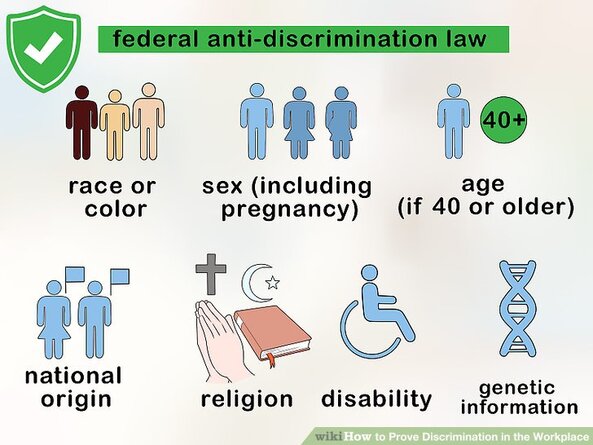

Social equality requires the absence of legally enforced social class or caste boundaries and the absence of discrimination motivated by an inalienable part of a person's identity. For example, sex, gender, race, age, sexual orientation, origin, caste or class, income or property, language, religion, convictions, opinions, health or disability must absolutely not result in unequal treatment under the law and should not reduce opportunities unjustifiably.

Equal opportunities is interpreted as being judged by ability, which is compatible with a free-market economy. Relevant problems are horizontal inequality − the inequality of two persons of same origin and ability and differing opportunities given to individuals − such as in (education) or by inherited capital.

Concepts of social equality may vary per philosophy and individual and other than egalitarianism it does not necessarily require all social inequalities to be eliminated by artificial means but instead often recognizes and respects natural differences between people.

The standard of equality that states everyone is created equal at birth is called ontological equality. This type of equality can be seen in many different places like the Declaration of Independence.

This early document, which states many of the values of the United States of America, has this idea of equality embedded in it. It clearly states that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights". The statement reflects the philosophy of John Locke and his idea that we are all equal in certain natural rights.

Although this standard of equality is seen in documents as important as the Declaration of Independence, it is "one not often invoked in policy debates these days". However this notion of equality is often used to justify inequalities such as material inequality.

Dalton Conley claims that ontological equality is used to justify material inequality by putting a spotlight on the fact, legitimated by theology, that "the distribution of power and resources here on earth does not matter, because all of us are equally children of God and will have to face our maker upon dying".

Dalton Conley, the author of You May Ask Yourself, claims that ontological equality can also be used to put forth the notion that poverty is virtue. Luciano Floridi, author of a book about information, wrote about what he calls the ontological equality principle. His work on information ethics raises the importance of equality when presenting information. Here is a short sample of his work:

Information ethics is impartial and universal because it brings to ultimate completion the process of enlargement of the concept of what may count as a center of a (no matter how minimal) moral claim, which now includes every instance of being understood informationally, no matter whether physically implemented or not.

In this respect information ethics holds that every entity as an expression of being, has a dignity constituted by its mode of existence and essence (the collection of all the elementary properties that constitute it for what it is), which deserve to be respected (at least in a minimal and overridable sense), and hence place moral claims on the interacting agent and ought to contribute to the constraint and guidance of his ethical decisions and behavior.

Floridi goes onto claim that this "ontological equality principle means that any form of reality (any instance of information/being), simply for the fact of being what it is, enjoys a minimal, initial, over-ridable, equal right to exist and develop in a way which is appropriate to its nature." Values in his claims correlate to those shown in the sociological textbook You May Ask Yourself by Dalton Conley.

The notion of "ontological equality" describes equality by saying everything is equal by nature. Everyone is created equal at birth. Everything has equal right to exist and develop by its nature.

Opportunity:

Main article: Equality of opportunity

Another standard of equality is equality of opportunity, "the idea that everyone has an equal chance to achieve wealth, social prestige, and power because the rules of the game, so to speak, are the same for everyone". This concept can be applied to society by saying that no one has a head start.

This means that, for any social equality issue dealing with wealth, social prestige, power, or any of that sort, the equality of opportunity standard can defend the idea that everyone had the same start.

This views society almost as a game and any of the differences in equality are due to luck and playing the "game" to one's best ability. Conley gives an example of this standard of equality by using a game of Monopoly to describe society.

He claims that "Monopoly follows the rules of equality of opportunity" by explaining that everyone had an equal chance when starting the game and any differences were a result of the luck of the dice roll and the skill of the player to make choices to benefit their wealth.

Comparing this example to society, the standard of equality of opportunity eliminates inequality because the rules of the games in society are still fair and the same for all; therefore making any existing inequalities in society fair.

Lesley A. Jacobs, the author of Pursuing Equal Opportunities: The Theory and Practice of Egalitarian Justice, talks about equality of opportunity and its importance relating to egalitarian justice.

Jacobs states that at the core of equality of opportunity... is the concept that in competitive procedures designed for the allocation of scarce resources and the distribution of the benefits and burdens of social life, those procedures should be governed by criteria that are relevant to the particular goods at stake in the competition and not by irrelevant considerations such as race, religion, class, gender, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or other factors that may hinder some of the competitors’ opportunities at success. (Jacobs, 10).This concept points out factors like race, gender, class etc. that should not be considered when talking about equality through this notion.

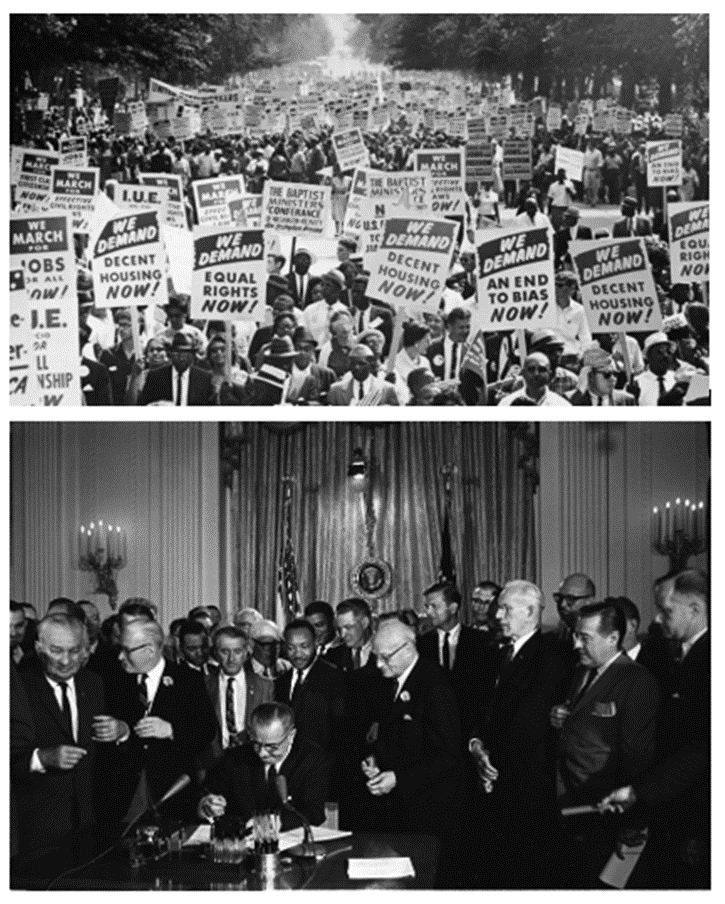

Conley also mentions that this standard of equality is at the heart of a bourgeois society, such as a modern capitalist society, or "a society of commerce in which the maximization of profit is the primary business incentive". It was the equal opportunity ideology that civil rights activists adopted in the era of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. This ideology was used by them to argue that Jim Crow laws were incompatible with the standard of equality of opportunity.

Condition:

Main article: Leveling mechanism

Another notion of equality introduced by Conley is equality of condition. Through this framework is the idea that everyone should have an equal starting point. Conley goes back to his example of a game of Monopoly to explain this standard. If the game of four started off with two players both having an advantage of $5,000 dollars to start off with and both already owning hotels and other property while the other two players both did not own any property and both started off with a $5,000 dollar deficit, then from a perspective of the standard of equality of condition, one can argue that the rules of the game "need to be altered in order to compensate for inequalities in the relative starting positions".

From this we form policies in order to even equality which in result bring an efficient way to create fairer competition in society. Here is where social engineering comes into play where we change society in order to give an equality of condition to everyone based on race, gender, class, religion etc. when it is made justifiable that the proponents of the society makes it unfair for them.

Sharon E. Kahn, author of Academic Freedom and the Inclusive University, talks about equality of condition in their work as well and how it correlates to freedom of individuals.

They claim that in order to have individual freedom there needs to be equality of condition "which requires much more than the elimination of legal barriers: it requires the creation of a level playing field that eliminates structural barriers to opportunity".

Kahn's work talks about the academic structure and its problem with equalities and claims that to "ensure equity...we need to recognize that the university structure and its organizational culture have traditionally privileged some and marginalized other; we need to go beyond theoretical concepts of equality by eliminating systemic barriers that hinder the equal participation of members of all groups; we need to create and equality of condition, not merely an equality of opportunity".

"Notions of equity, diversity, and inclusiveness begin with a set of premises about individualism, freedom and rights that take as given the existence of deeply rooted inequalities in social structure," therefore in order to have a culture of the inclusive university, it would have to "be based on values of equity; that is, equality of condition" eliminating all systemic barriers that go against equality.

Outcome:

Main article: Equality of outcome

A fourth standard of equality is equality of outcome, which is "a position that argues each player must end up with the same amount regardless of the fairness". This ideology is predominately a Marxist philosophy that is concerned with equal distribution of power and resources rather than the rules of society. In this standard of equality, the idea is that "everyone contributes to society and to the economy according to what they do best".

Under this notion of equality, Conley states that "nobody will earn more power, prestige, and wealth by working harder".

When defining equality of outcome in education, "the goals should not be the liberal one of equality of access but equality of outcome for the median number of each identifiable non-educationally defined group, i.e. the average women, negro, or proletarian or rural dweller should have the same level of educational attainment as the average male, white, suburbanite".

The outcome and the benefits from equality from education from this notion of equality promotes that all should have the same outcomes and benefits regardless of race, gender, religion etc. The equality of outcome in Hewitt's point of view is supposed to result in "a comparable range of achievements between a specific disadvantaged group – such as an ethnic minority, women, lone parents and the disabled – and society as a whole".

___________________________________________________________________________

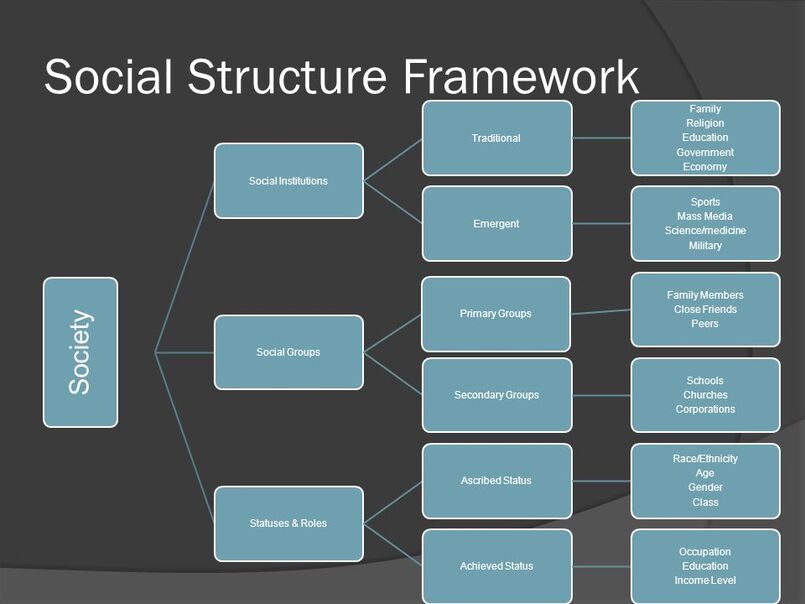

Social inequality occurs when resources in a given society are distributed unevenly, typically through norms of allocation, that engender specific patterns along lines of socially defined categories of persons.

It is the differentiation preference of access of social goods in the society brought about by power, religion, kinship, prestige, race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and class.

The social rights include labor market, the source of income, health care, and freedom of speech, education, political representation, and participation. Social inequality linked to economic inequality, usually described on the basis of the unequal distribution of income or wealth, is a frequently studied type of social inequality.

Although the disciplines of economics and sociology generally use different theoretical approaches to examine and explain economic inequality, both fields are actively involved in researching this inequality. However, social and natural resources other than purely economic resources are also unevenly distributed in most societies and may contribute to social status.

Norms of allocation can also affect the distribution of rights and privileges, social power, access to public goods such as education or the judicial system, adequate housing, transportation, credit and financial services such as banking and other social goods and services.

Many societies worldwide claim to be meritocracies—that is, that their societies exclusively distribute resources on the basis of merit. The term "meritocracy" was coined by Michael Young in his 1958 dystopian essay "The Rise of the Meritocracy" to demonstrate the social dysfunctions that he anticipated arising in societies where the elites believe that they are successful entirely on the basis of merit, so the adoption of this term into English without negative connotations is ironic.

Young was concerned that the Tripartite System of education being practiced in the United Kingdom at the time he wrote the essay considered merit to be "intelligence-plus-effort, its possessors ... identified at an early age and selected for appropriate intensive education" and that the "obsession with quantification, test-scoring, and qualifications" it supported would create an educated middle-class elite at the expense of the education of the working class, inevitably resulting in injustice and – eventually – revolution. A modern representation of the sort of "meritocracy" Young feared may be seen in the series 3%.

Although merit matters to some degree in many societies, research shows that the distribution of resources in societies often follows hierarchical social categorizations of persons to a degree too significant to warrant calling these societies "meritocratic", since even exceptional intelligence, talent, or other forms of merit may not be compensatory for the social disadvantages people face.

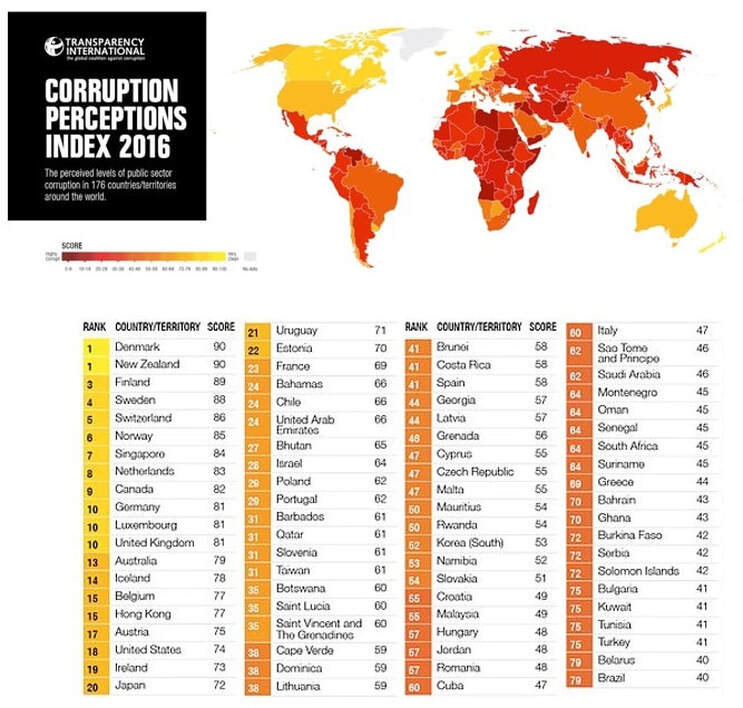

In many cases, social inequality is linked to racial inequality, ethnic inequality, and gender inequality, as well as other social statuses and these forms can be related to corruption.

The most common metric for comparing social inequality in different nations is the Gini coefficient, which measures the concentration of wealth and income in a nation from 0 (evenly distributed wealth and income) to 1 (one person has all wealth and income). Two nations may have identical Gini coefficients but dramatically different economic (output) and/or quality of life, so the Gini coefficient must be contextualized for meaningful comparisons to be made.

Overview:

Social inequality is found in almost every society. Social inequality is shaped by a range of structural factors, such as geographical location or citizenship status, and are often underpinned by cultural discourses and identities defining, for example, whether the poor are 'deserving' or 'undeserving'.

In simple societies, those that have few social roles and statuses occupied by its members, social inequality may be very low. In tribal societies, for example, a tribal head or chieftain may hold some privileges, use some tools, or wear marks of office to which others do not have access, but the daily life of the chieftain is very much like the daily life of any other tribal member.

Anthropologists identify such highly egalitarian cultures as "kinship-oriented", which appear to value social harmony more than wealth or status. These cultures are contrasted with materially oriented cultures in which status and wealth are prized and competition and conflict are common. Kinship-oriented cultures may actively work to prevent social hierarchies from developing because they believe that could lead to conflict and instability.

In today's world, most of our population lives in more complex than simple societies. As social complexity increases, inequality tends to increase along with a widening gap between the poorest and the most wealthy members of society.

Social inequality can be classified into egalitarian societies, ranked society, and stratified society.

Egalitarian societies are those communities advocating for social equality through equal opportunities and rights, hence no discrimination. People with special skills were not viewed as superior compared to the rest. The leaders do not have the power they only have influence.

The norms and the beliefs the egalitarian society holds are for sharing equally and equal participation. Simply there are no classes. Ranked society mostly is agricultural communities who hierarchically grouped from the chief who is viewed to have a status in the society. In this society, people are clustered regarding status and prestige and not by access to power and resources.

The chief is the most influential person followed by his family and relative, and those further related to him are less ranked. Stratified society is societies which horizontally ranked into the upper class, middle class, and lower class. The classification is regarding wealth, power, and prestige.

The upper class are mostly the leaders and are the most influential in the society. It's possible for a person in the society to move from one stratum to the other. The social status is also hereditable from one generation to the next.

There are five systems or types of social inequality:

- wealth inequality,

- treatment and responsibility inequality,

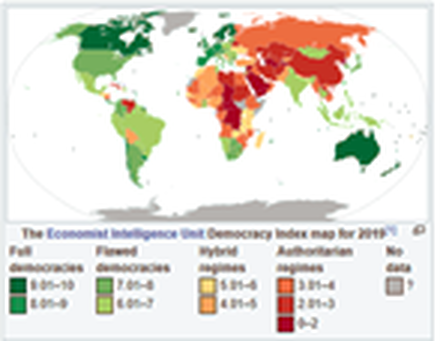

- political inequality,

- life inequality,

- and membership inequality.

Political inequality is the difference brought about by the ability to access governmental resources which therefore have no civic equality. In treatment and responsibility differences, some people benefit more and can quickly receive more privileges than others.

In working stations, some are given more responsibilities and hence better compensation and more benefits than the rest even when equally qualified. Membership inequality is the number of members in a family, nation or faith. Life inequality is brought about by the disparity of opportunities which, if present, improve a person’s life quality.

Finally, income and wealth inequality is the disparity due to what an individual can earn on a daily basis contributing to their total revenue either monthly or yearly.

The major examples of social inequality include income gap, gender inequality, health care, and social class. In health care, some individuals receive better and more professional care compared to others. They are also expected to pay more for these services. Social class differential comes evident during the public gathering where upper-class people given the best places to seat, the hospitality they receive and the first priorities they receive.

Status in society is of two types which are ascribed characteristics and achieved characteristics. Ascribed characteristics are those present at birth or assigned by others and over which an individual has little or no control. Examples include sex, skin colour, eye shape, place of birth, sexuality, gender identity, parentage and social status of parents.

Achieved characteristics are those which we earn or choose; examples include level of education, marital status, leadership status and other measures of merit. In most societies, an individual's social status is a combination of ascribed and achieved factors.

In some societies, however, only ascribed statuses are considered in determining one's social status and there exists little to no social mobility and, therefore, few paths to more social equality. This type of social inequality is generally referred to as caste inequality.

One's social location in a society's overall structure of social stratification affects and is affected by almost every aspect of social life and one's life chances. The single best predictor of an individual's future social status is the social status into which they were born.

Theoretical approaches to explaining social inequality concentrate on questions about how such social differentiations arise, what types of resources are being allocated (for example, reserves versus resources), what are the roles of human cooperation and conflict in allocating resources, and how do these differing types and forms of inequality affect the overall functioning of a society?

The variables considered most important in explaining inequality and the manner in which those variables combine to produce the inequities and their social consequences in a given society can change across time and place.

In addition to interest in comparing and contrasting social inequality at local and national levels, in the wake of today's globalizing processes, the most interesting question becomes: what does inequality look like on a worldwide scale and what does such global inequality bode for the future? In effect, globalization reduces the distances of time and space, producing a global interaction of cultures and societies and social roles that can increase global inequities.

Inequality and ideology:

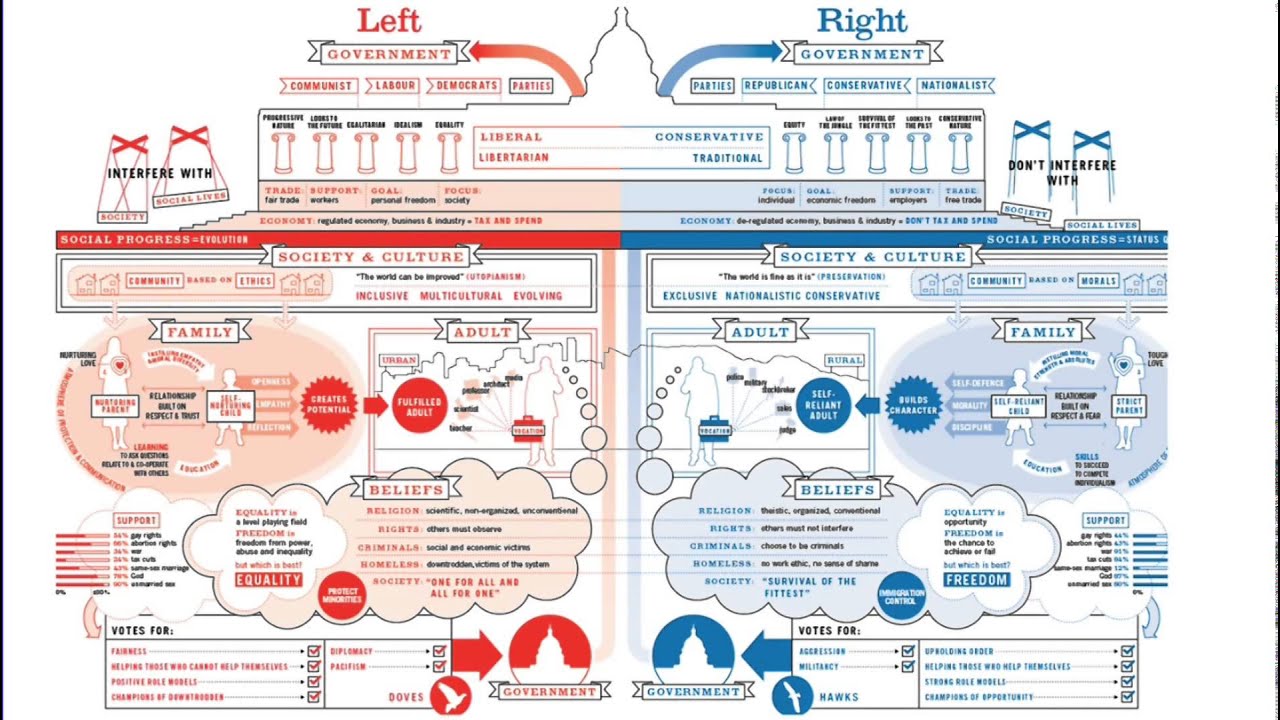

Philosophical questions about social ethics and the desirability or inevitability of inequality in human societies have given rise to a spate of ideologies to address such questions. We can broadly classify these ideologies on the basis of whether they justify or legitimize inequality, casting it as desirable or inevitable, or whether they cast equality as desirable and inequality as a feature of society to be reduced or eliminated.

One end of this ideological continuum can be called "Individualist", the other "Collectivist".

In Western societies, there is a long history associated with the idea of individual ownership of property and economic liberalism, the ideological belief in organizing the economy on individualist lines such that the greatest possible number of economic decisions are made by individuals and not by collective institutions or organizations.

Laissez-faire, free market ideologies—including classical liberalism, neoliberalism, and libertarianism—are formed around the idea that social inequality is a "natural" feature of societies, is therefore inevitable and, in some philosophies, even desirable.

Inequality provides for differing goods and services to be offered on the open market, spurs ambition, and provides incentive for industriousness and innovation. At the other end of the continuum, collectivists place little to no trust in "free market" economic systems, noting widespread lack of access among specific groups or classes of individuals to the costs of entry to the market.

Widespread inequalities often lead to conflict and dissatisfaction with the current social order. Such ideologies include Fabianism and socialism. Inequality, in these ideologies, must be reduced, eliminated, or kept under tight control through collective regulation.

Furthermore, in some views inequality is natural but shouldn't affect certain fundamental human needs, human rights and the initial chances given to individuals (e.g. by education) and is out of proportions due to various problematic systemic structures.

Though the above discussion is limited to specific Western ideologies, similar thinking can be found, historically, in differing societies throughout the world. While, in general, eastern societies tend toward collectivism, elements of individualism and free market organization can be found in certain regions and historical eras.

Classic Chinese society in the Han and Tang dynasties, for example, while highly organized into tight hierarchies of horizontal inequality with a distinct power elite also had many elements of free trade among its various regions and subcultures.

Social mobility is the movement along social strata or hierarchies by individuals, ethnic group, or nations. There is a change in literacy, income distribution, education and health status. The movement can be vertical or horizontal.

- Vertical is the upward or downward movement along social strata which occurs due to change of jobs or marriage.

- Horizontal movement along levels that are equally ranked. Intra-generational mobility is a social status change in a generation (single lifetime).

For example, a person moves from a junior staff in an organization to the senior management. The absolute management movement is where a person gains better social status than their parents, and this can be due to improved security, economic development, and better education system. Relative mobility is where some individual are expected to have higher social ranks than their parents.

Today, there is belief held by some that social inequality often creates political conflict and growing consensus that political structures determine the solution for such conflicts. Under this line of thinking, adequately designed social and political institutions are seen as ensuring the smooth functioning of economic markets such that there is political stability, which improves the long-term outlook, enhances labor and capital productivity and so stimulates economic growth.

With higher economic growth, net gains are positive across all levels and political reforms are easier to sustain. This may explain why, over time, in more egalitarian societies fiscal performance is better, stimulating greater accumulation of capital and higher growth.

Inequality and social class:

Main article: Social class

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a combined total measure of a person's work experience and of an individual's or family's economic and social position in relation to others, based on income, education, and occupation. It is often used as synonymous with social class, a set of hierarchical social categories that indicate an individual's or household's relative position in a stratified matrix of social relationships.

Social class is delineated by a number of variables, some of which change across time and place. For Karl Marx, there exist two major social classes with significant inequality between the two. The two are delineated by their relationship to the means of production in a given society. Those two classes are defined as the owners of the means of production and those who sell their labor to the owners of the means of production.

In capitalistic societies, the two classifications represent the opposing social interests of its members, capital gain for the capitalists and good wages for the laborers, creating social conflict.

Max Weber uses social classes to examine wealth and status. For him, social class is strongly associated with prestige and privileges. It may explain social reproduction, the tendency of social classes to remain stable across generations maintaining most of their inequalities as well.

Such inequalities include differences in income, wealth, access to education, pension levels, social status, socioeconomic safety-net. In general, social class can be defined as a large category of similarly ranked people located in a hierarchy and distinguished from other large categories in the hierarchy by such traits as occupation, education, income, and wealth.

In modern Western societies, inequalities are often broadly classified into three major divisions of social class: upper class, middle class, and lower class. Each of these classes can be further subdivided into smaller classes (e.g. "upper middle"). Members of different classes have varied access to financial resources, which affects their placement in the social stratification system.

Class, race, and gender are forms of stratification that bring inequality and determines the difference in allocation of societal rewards. Occupation is the primary determinant of a person class since it affects their lifestyle, opportunities, culture, and kind of people one associates with. Class based families include the lower class who are the poor in the society. They have limited opportunities.

Working class are those people in blue-collar jobs and usually, affects the economic level of a nation. The Middle classes are those who rely mostly on wives' employment and depends on credits from the bank and medical coverage. The upper middle class are professionals who are strong because of economic resources and supportive institutions. Additionally, the upper class usually are the wealthy families who have economic power due to accumulative wealth from families but not and not hard earned income.

Social stratification is the hierarchical arrangement of society about social class, wealth, political influence. A society can be politically stratified based on authority and power, economically stratified based on income level and wealth, occupational stratification about one's occupation. Some roles for examples doctors, engineers, lawyers are highly ranked, and thus they give orders while the rest receive the orders.

There are three systems of social stratification which are the caste system, estates system, and class system. Castes system usually ascribed to children during birth whereby one receives the same stratification as of that of their parents. The caste system has been linked to religion and thus permanent. The stratification may be superior or inferior and thus influences the occupation and the social roles assigned to a person.

Estate system is a state or society where people in this state were required to work on their land to receive some services like military protection. Communities ranked according to the nobility of their lords. The class system is about income inequality and socio-political status.

People can move the classes when they increase their level of income or if they have authority. People are expected to maximize their innate abilities and possessions. Social stratification characteristics include its universal, social, ancient, it’s in diverse forms and also consequential.

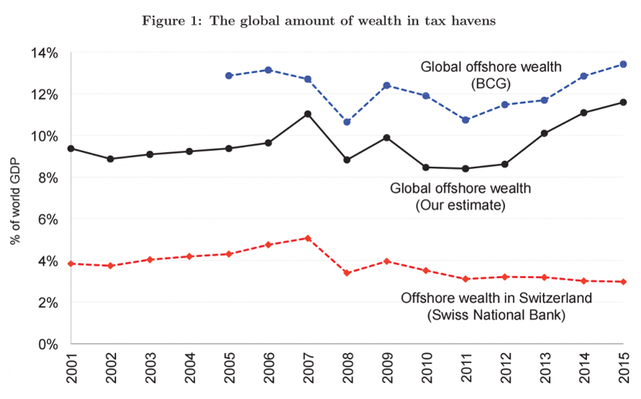

The quantitative variables most often used as an indicator of social inequality are income and wealth. In a given society, the distribution of individual or household accumulation of wealth tells us more about variation in well-being than does income, alone. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), especially per capita GDP, is sometimes used to describe economic inequality at the international or global level.

A better measure at that level, however, is the Gini coefficient, a measure of statistical dispersion used to represent the distribution of a specific quantity, such as income or wealth, at a global level, among a nation's residents, or even within a metropolitan area. Other widely used measures of economic inequality are the percentage of people living with under US$1.25 or $2 a day and the share of national income held by the wealthiest 10% of the population, sometimes called "the Palma" measure.

Patterns of inequality:

There are a number of socially defined characteristics of individuals that contribute to social status and, therefore, equality or inequality within a society. When researchers use quantitative variables such as income or wealth to measure inequality, on an examination of the data, patterns are found that indicate these other social variables contribute to income or wealth as intervening variables.

Significant inequalities in income and wealth are found when specific socially defined categories of people are compared. Among the most pervasive of these variables are sex/gender, race, and ethnicity. This is not to say, in societies wherein merit is considered to be the primary factor determining one's place or rank in the social order, that merit has no effect on variations in income or wealth.

It is to say that these other socially defined characteristics can, and often do, intervene in the valuation of merit.

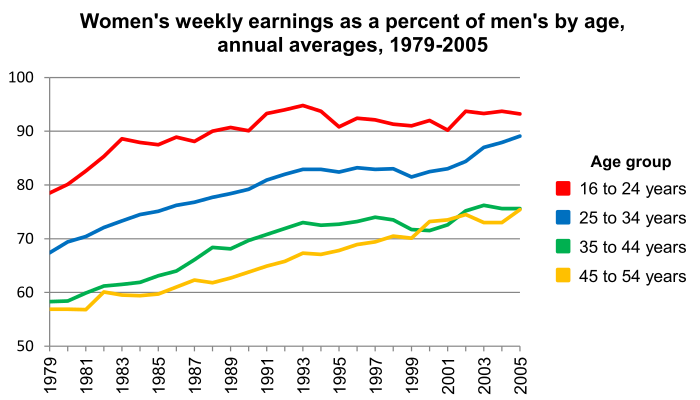

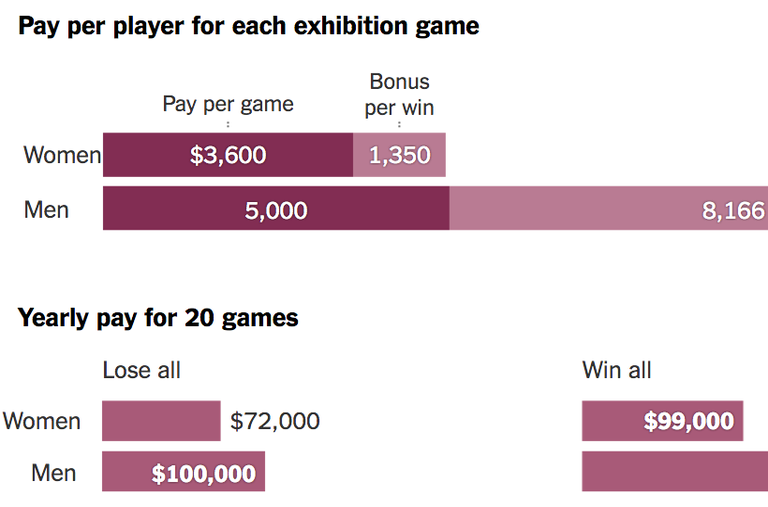

Gender inequality:

Gender as a social inequality is whereby women and men are treated differently due to masculinity and femininity by dividing labor, assigning roles, and responsibilities and allocating social rewards. Sex- and gender-based prejudice and discrimination, called sexism, are major contributing factors to social inequality.

Most societies, even agricultural ones, have some sexual division of labor and gender-based division of labor tends to increase during industrialization. The emphasis on gender inequality is born out of the deepening division in the roles assigned to men and women, particularly in the economic, political and educational spheres. Women are underrepresented in political activities and decision making processes in most states in both the Global North and Global South.

Gender discrimination, especially concerning the lower social status of women, has been a topic of serious discussion not only within academic and activist communities but also by governmental agencies and international bodies such as the United Nations.

These discussions seek to identify and remedy widespread, institutionalized barriers to access for women in their societies. By making use of gender analysis, researchers try to understand the social expectations, responsibilities, resources and priorities of women and men within a specific context, examining the social, economic and environmental factors which influence their roles and decision-making capacity.

By enforcing artificial separations between the social and economic roles of men and women, the lives of women and girls are negatively impacted and this can have the effect of limiting social and economic development.

Cultural ideals about women's work can also affect men whose outward gender expression is considered "feminine" within a given society. Transgender and gender-variant persons may express their gender through their appearance, the statements they make, or official documents they present.

In this context, gender normality, which is understood as the social expectations placed on us when we present particular bodies, produces widespread cultural/institutional devaluations of trans identities, homosexuality and femininity. Trans persons, in particular, have been defined as socially unproductive and disruptive.

A variety of global issues like HIV/AIDS, illiteracy, and poverty are often seen as "women's issues" since women are disproportionately affected. In many countries, women and girls face problems such as lack of access to education, which limit their opportunities to succeed, and further limits their ability to contribute economically to their society.

Women are underrepresented in political activities and decision making processes throughout most of the world. As of 2007, around 20 percent of women were below the $1.25/day international poverty line and 40 percent below the $2/day mark. More than one-quarter of females under the age of 25 were below the $1.25/day international poverty line and about half on less than $2/day.

Women's participation in work has been increasing globally, but women are still faced with wage discrepancies and differences compared to what men earn. This is true globally even in the agricultural and rural sector in developed as well as developing countries.

Structural impediments to women's ability to pursue and advance in their chosen professions often result in a phenomenon known as the glass ceiling, which refers to unseen – and often unacknowledged barriers that prevent minorities and women from rising to the upper rungs of the corporate ladder, regardless of their qualifications or achievements.

This effect can be seen in the corporate and bureaucratic environments of many countries, lowering the chances of women to excel. It prevents women from succeeding and making the maximum use of their potential, which is at a cost for women as well as the society's development. Ensuring that women's rights are protected and endorsed can promote a sense of belonging that motivates women to contribute to their society. Once able to work, women should be titled to the same job security and safe working environments as men.

Until such safeguards are in place, women and girls will continue to experience not only barriers to work and opportunities to earn, but will continue to be the primary victims of discrimination, oppression, and gender-based violence.

Women and persons whose gender identity does not conform to patriarchal beliefs about sex (only male and female) continue to face violence on global domestic, interpersonal, institutional and administrative scales.

While first-wave Liberal Feminist initiatives raised awareness about the lack of fundamental rights and freedoms that women have access to, second-wave feminism (see also Radical Feminism) highlighted the structural forces that underlie gender-based violence. Masculinities are generally constructed so as to subordinate femininities and other expressions of gender that are not heterosexual, assertive and dominant.

Gender sociologist and author, Raewyn Connell, discusses in her 2009 book, Gender, how masculinity is dangerous, heterosexual, violent and authoritative. These structures of masculinity ultimately contribute to the vast amounts of gendered violence, marginalization and suppression that women, queer, transgender, gender variant and gender non-conforming persons face.

Some scholars suggest that women's under-representation in political systems speaks the idea that "formal citizenship does not always imply full social membership". Men, male bodies and expressions of masculinity are linked to ideas about work and citizenship. Others point out that patriarchal states tend top scale and claw back their social policies relative to the disadvantage of women. This process ensures that women encounter resistance into meaningful positions of power in institutions, administrations, and political systems and communities.

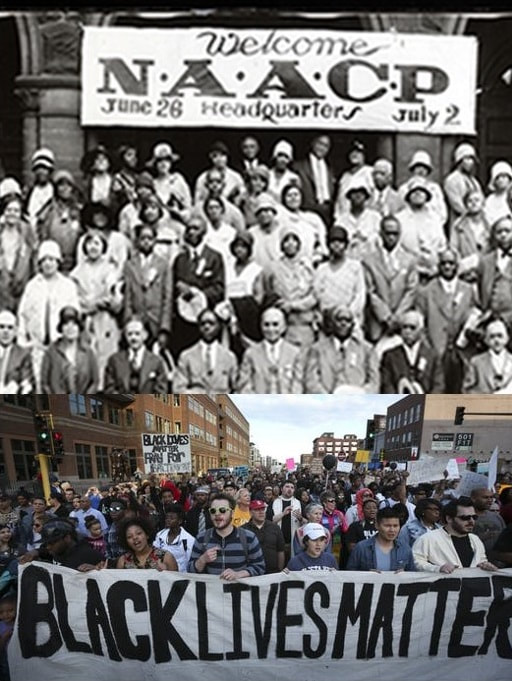

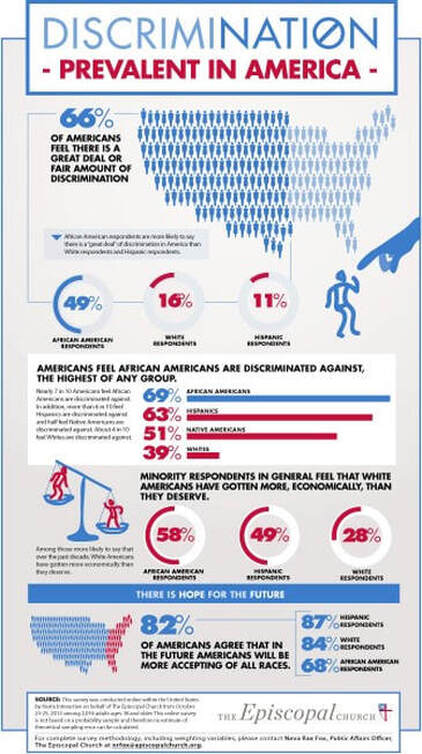

Racial and ethnic inequality:

Racial or ethnic inequality is the result of hierarchical social distinctions between racial and ethnic categories within a society and often established based on characteristics such as skin color and other physical characteristics or an individual's place of origin or culture. Racism is whereby some races are more privileged and are allowed to venture into the labor market and are better compensated than others.

Ethnicity is the privilege one enjoys for belonging to a particular ethnic group. Even though race has no biological connection, it has become a socially constructed category capable of restricting or enabling social status.

Racial inequality can also result in diminished opportunities for members of marginalized groups, which in turn can lead to cycles of poverty and political marginalization. Racial and ethnic categories become a minority category in a society.

Minority members in such a society are often subjected to discriminatory actions resulting from majority policies, including assimilation, exclusion, oppression, expulsion, and extermination.

For example, during the run-up to the 2012 federal elections in the United States, legislation in certain "battleground states" that claimed to target voter fraud had the effect of disenfranchising tens of thousands of primarily African American voters.

These types of institutional barriers to full and equal social participation have far-reaching effects within marginalized communities, including reduced economic opportunity and output, reduced educational outcomes and opportunities and reduced levels of overall health.

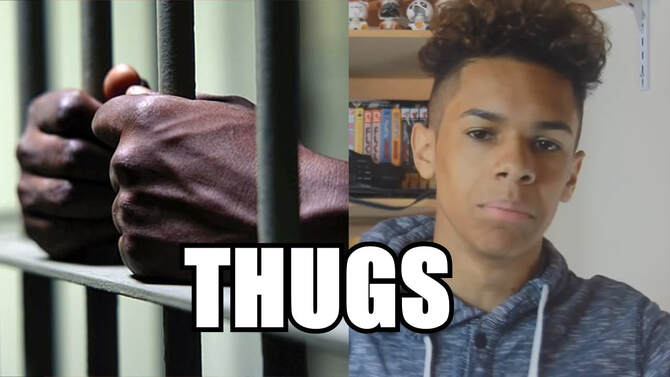

In the United States, Angela Davis argues that mass incarceration has been a modern tool of the state to impose inequality, repression, and discrimination upon African American and Hispanics. The War on Drugs has been a campaign with disparate effects, ensuring the constant incarceration of poor, vulnerable, and marginalized populations in North America.

Over a million African Americans are incarcerated in the US, many of whom have been convicted of a non-violent drug possession charge.

With the States of Colorado and Washington having legalized the possession of marijuana, drug reformists and anti-war on drugs lobbyists are hopeful that drug issues will be interpreted and dealt with from a healthcare perspective instead of a matter of criminal law.

In Canada, Aboriginal, First Nations, and Indigenous persons represent over a quarter of the federal prison population, even though they only represent 3% of the country's population.

Age inequality:

Age discrimination is defined as the unfair treatment of people with regard to promotions, recruitment, resources, or privileges because of their age. It is also known as ageism: the stereotyping of and discrimination against individuals or groups based upon their age. It is a set of beliefs, attitudes, norms, and values used to justify age-based prejudice, discrimination, and subordination.

One form of ageism is adultism, which is the discrimination against children and people under the legal adult age. An example of an act of adultism might be the policy of a certain establishment, restaurant, or place of business to not allow those under the legal adult age to enter their premises after a certain time or at all.

While some people may benefit or enjoy these practices, some find them offensive and discriminatory. Discrimination against those under the age of 40 however is not illegal under the current U.S. Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA).

As implied in the definitions above, treating people differently based upon their age is not necessarily discrimination. Virtually every society has age-stratification, meaning that the age structure in a society changes as people begin to live longer and the population becomes older.

In most cultures, there are different social role expectations for people of different ages to perform. Every society manages people's ageing by allocating certain roles for different age groups. Age discrimination primarily occurs when age is used as an unfair criterion for allocating more or less resources.

Scholars of age inequality have suggested that certain social organizations favor particular age inequalities. For instance, because of their emphasis on training and maintaining productive citizens, modern capitalist societies may dedicate disproportionate resources to training the young and maintaining the middle-aged worker to the detriment of the elderly and the retired (especially those already disadvantaged by income/wealth inequality).

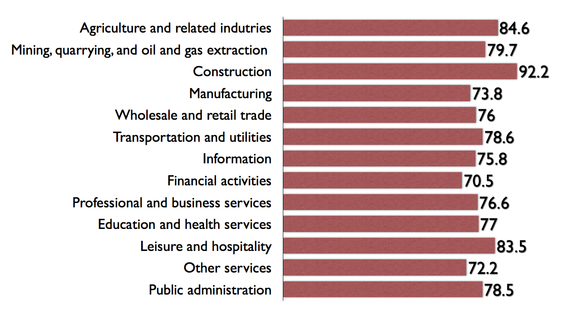

In modern, technologically advanced societies, there is a tendency for both the young and the old to be relatively disadvantaged. However, more recently, in the United States the tendency is for the young to be most disadvantaged. For example, poverty levels in the U.S. have been decreasing among people aged 65 and older since the early 1970s whereas the number of children under 18 in poverty has steadily risen.

Sometimes, the elderly have had the opportunity to build their wealth throughout their lives, while younger people have the disadvantage of recently entering into or having not yet entered into the economic sphere. The larger contributor to this, however, is the increase in the number of people over 65 receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits in the U.S.

When we compare income distribution among youth across the globe, we find that about half (48.5 percent) of the world's young people are confined to the bottom two income brackets as of 2007. This means that, out of the three billion persons under the age of 24 in the world as of 2007, approximately 1.5 billion were living in situations in which they and their families had access to just nine percent of global income.

Moving up the income distribution ladder, children and youth do not fare much better: more than two-thirds of the world's youth have access to less than 20 percent of global wealth, with 86 percent of all young people living on about one-third of world income. For the just over 400 million youth who are fortunate enough to rank among families or situations at the top of the income distribution, however, opportunities improve greatly with more than 60 percent of global income within their reach.

Although this does not exhaust the scope of age discrimination, in modern societies it is often discussed primarily with regards to the work environment. Indeed, non-participation in the labour force and the unequal access to rewarding jobs means that the elderly and the young are often subject to unfair disadvantages because of their age. On the one hand, the elderly are less likely to be involved in the workforce.

At the same time, old age may or may not put one at a disadvantage in accessing positions of prestige. Old age may benefit one in such positions, but it may also disadvantage one because of negative ageist stereotyping of old people. On the other hand, young people are often disadvantaged from accessing prestigious or relatively rewarding jobs, because of their recent entry to the work force or because they are still completing their education.

Typically, once they enter the labor force or take a part-time job while in school, they start at entry level positions with low level wages. Furthermore, because of their lack of prior work experience, they can also often be forced to take marginal jobs, where they can be taken advantage of by their employers. As a result, many older people have to face obstacles in their lives.

Inequalities in health:

Further information:

- Health equity,

- Inequality in disease,

- Social determinants of health in poverty,

- and Diseases of poverty

Health inequalities can be defined as differences in health status or in the distribution of health determinants between different population groups.

Health care:

Health inequalities are in many cases related to access to health care. In industrialized nations, health inequalities are most prevalent in countries that have not implemented a universal health care system, such as the United States.

Because the US health care system is heavily privatized, access to health care is dependent upon one's economic capital; Health care is not a right, it is a commodity that can be purchased through private insurance companies (or that is sometimes provided through an employer).

The way health care is organized in the U.S. contributes to health inequalities based on gender, socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. As Wright and Perry assert, "social status differences in health care are a primary mechanism of health inequalities".

In the United States, over 48 million people are without medical care coverage. This means that almost one sixth of the population is without health insurance, mostly people belonging to the lower classes of society.

While universal access to health care may not completely eliminate health inequalities, it has been shown that it greatly reduces them. In this context, privatization gives individuals the 'power' to purchase their own health care (through private health insurance companies), but this leads to social inequality by only allowing people who have economic resources to access health care.

Citizens are seen as consumers who have a 'choice' to buy the best health care they can afford; in alignment with neoliberal ideology, this puts the burden on the individual rather than the government or the community.

In countries that have a universal health care system, health inequalities have been reduced. In Canada, for example, equity in the availability of health services has been improved dramatically through Medicare. People don't have to worry about how they will pay health care, or rely on emergency rooms for care, since health care is provided for the entire population.

However, inequality issues still remain. For example, not everyone has the same level of access to services. Inequalities in health are not, however, only related to access to health care. Even if everyone had the same level of access, inequalities may still remain.

This is because health status is a product of more than just how much medical care people have available to them. While Medicare has equalized access to health care by removing the need for direct payments at the time of services, which improved the health of low status people, inequities in health are still prevalent in Canada. This may be due to the state of the current social system, which bear other types of inequalities such as economic, racial and gender inequality.

A lack of health equity is also evident in the developing world, where the importance of equitable access to healthcare has been cited as crucial to achieving many of the Millennium Development Goals. Health inequalities can vary greatly depending on the country one is looking at. Health equity is needed in order to live a healthier and more sufficient life within society.

Inequalities in health lead to substantial effects, that is burdensome or the entire society. Inequalities in health are often associated with socioeconomic status and access to health care. Health inequities can occur when the distribution of public health services is unequal.

For example, in Indonesia in 1990, only 12% of government spending for health was for services consumed by the poorest 20% of households, while the wealthiest 20% consumed 29% of the government subsidy in the health sector.

Access to health care is heavily influenced by socioeconomic status as well, as wealthier population groups have a higher probability of obtaining care when they need it. A study by Makinen et al. (2000) found that in the majority of developing countries they looked at, there was an upward trend by quantile in health care use for those reporting illness.

Wealthier groups are also more likely to be seen by doctors and to receive medicine.

Food:

There has been considerable research in recent years regarding a phenomenon known as food deserts, in which low access to fresh, healthy food in a neighborhood leads to poor consumer choices and options regarding diet.

It is widely thought that food deserts are significant contributors to the childhood obesity epidemic in the United States and many other countries. This may have significant impacts on the local level as well as in broader contexts, such as in Greece, where the childhood obesity rate has skyrocketed in recent years heavily as a result of the rampant poverty and the resultant lack of access to fresh foods.

Global inequality:

See also: International inequality

The economies of the world have developed unevenly, historically, such that entire geographical regions were left mired in poverty and disease while others began to reduce poverty and disease on a wholesale basis.

This was represented by a type of North–South divide that existed after World War II between First world, more developed, industrialized, wealthy countries and Third world countries, primarily as measured by GDP.

From around 1980, however, through at least 2011, the GDP gap, while still wide, appeared to be closing and, in some more rapidly developing countries, life expectancies began to rise. However, there are numerous limitations of GDP as an economic indicator of social "well-being."

If we look at the Gini coefficient for world income, over time, after World War II the global Gini coefficient sat at just under .45. From around 1959 to 1966, the global Gini increased sharply, to a peak of around .48 in 1966.

After falling and leveling off a couple of times during a period from around 1967 to 1984, the Gini began to climb again in the mid-eighties until reaching a high or around .54 in 2000 then jumped again to around .70 in 2002.

Since the late 1980s, the gap between some regions has markedly narrowed— between Asia and the advanced economies of the West, for example—but huge gaps remain globally.

Overall equality across humanity, considered as individuals, has improved very little. Within the decade between 2003 and 2013, income inequality grew even in traditionally egalitarian countries like Germany, Sweden and Denmark. With a few exceptions—France, Japan, Spain—the top 10 percent of earners in most advanced economies raced ahead, while the bottom 10 percent fell further behind.

By 2013, a tiny elite of multi-billionaires, 85 to be exact, had amassed wealth equivalent to all the wealth owned by the poorest half (3.5 billion) of the world's total population of 7 billion. Country of citizenship (an ascribed status characteristic) explains 60% of variability in global income; citizenship and parental income class (both ascribed status characteristics) combined explain more than 80% of income variability.

Inequality and economic growth:

The concept of economic growth is fundamental in capitalist economies. Productivity must grow as population grows and capital must grow to feed into increased productivity.

Investment of capital leads to returns on investment (ROI) and increased capital accumulation. The hypothesis that economic inequality is a necessary precondition for economic growth has been a mainstay of liberal economic theory.

Recent research, particularly over the first two decades of the 21st century, has called this basic assumption into question. While growing inequality does have a positive correlation with economic growth under specific sets of conditions, inequality in general is not positively correlated with economic growth and, under some conditions, shows a negative correlation with economic growth.

Milanovic (2011) points out that overall, global inequality between countries is more important to growth of the world economy than inequality within countries. While global economic growth may be a policy priority, recent evidence about regional and national inequalities cannot be dismissed when more local economic growth is a policy objective.

The recent financial crisis and global recession hit countries and shook financial systems all over the world. This led to the implementation of large-scale fiscal expansionary interventions and, as a result, to massive public debt issuance in some countries.

Governmental bailouts of the banking system further burdened fiscal balances and raises considerable concern about the fiscal solvency of some countries. Most governments want to keep deficits under control but rolling back the expansionary measures or cutting spending and raising taxes implies an enormous wealth transfer from tax payers to the private financial sector.

Expansionary fiscal policies shift resources and causes worries about growing inequality within countries. Moreover, recent data confirm an ongoing trend of increasing income inequality since the early nineties. Increasing inequality within countries has been accompanied by a redistribution of economic resources between developed economies and emerging markets.

Davtyn, et al. (2014) studied the interaction of these fiscal conditions and changes in fiscal and economic policies with income inequality in the UK, Canada, and the US. They find income inequality has negative effect on economic growth in the case of the UK but a positive effect in the cases of the US and Canada.

Income inequality generally reduces government net lending/borrowing for all the countries. Economic growth, they find, leads to an increase of income inequality in the case of the UK and to the decline of inequality in the cases of the US and Canada.

At the same time, economic growth improves government net lending/borrowing in all the countries. Government spending leads to the decline in inequality in the UK but to its increase in the US and Canada.

Following the results of Alesina and Rodrick (1994), Bourguignon (2004), and Birdsall (2005) show that developing countries with high inequality tend to grow more slowly, Ortiz and Cummings (2011) show that developing countries with high inequality tend to grow more slowly. For 131 countries for which they could estimate the change in Gini index values between 1990 and 2008, they find that those countries that increased levels of inequality experienced slower annual per capita GDP growth over the same time period.

Noting a lack of data for national wealth, they build an index using Forbes list of billionaires by country normalized by GDP and validated through correlation with a Gini coefficient for wealth and the share of wealth going to the top decile.

They find that many countries generating low rates of economic growth are also characterized by a high level of wealth inequality with wealth concentration among a class of entrenched elites.

They conclude that extreme inequality in the distribution of wealth globally, regionally and nationally, coupled with the negative effects of higher levels of income disparities, should make us question current economic development approaches and examine the need to place equity at the center of the development agenda.

Ostry, et al. (2014) reject the hypothesis that there is a major trade-off between a reduction of income inequality (through income redistribution) and economic growth. If that were the case, they hold, then redistribution that reduces income inequality would on average be bad for growth, taking into account both the direct effect of higher redistribution and the effect of the resulting lower inequality.

Their research shows rather the opposite: increasing income inequality always has a significant and, in most cases, negative effect on economic growth while redistribution has an overall pro-growth effect (in one sample) or no growth effect. Their conclusion is that increasing inequality, particularly when inequality is already high, results in low growth, if any, and such growth may be unsustainable over long periods.

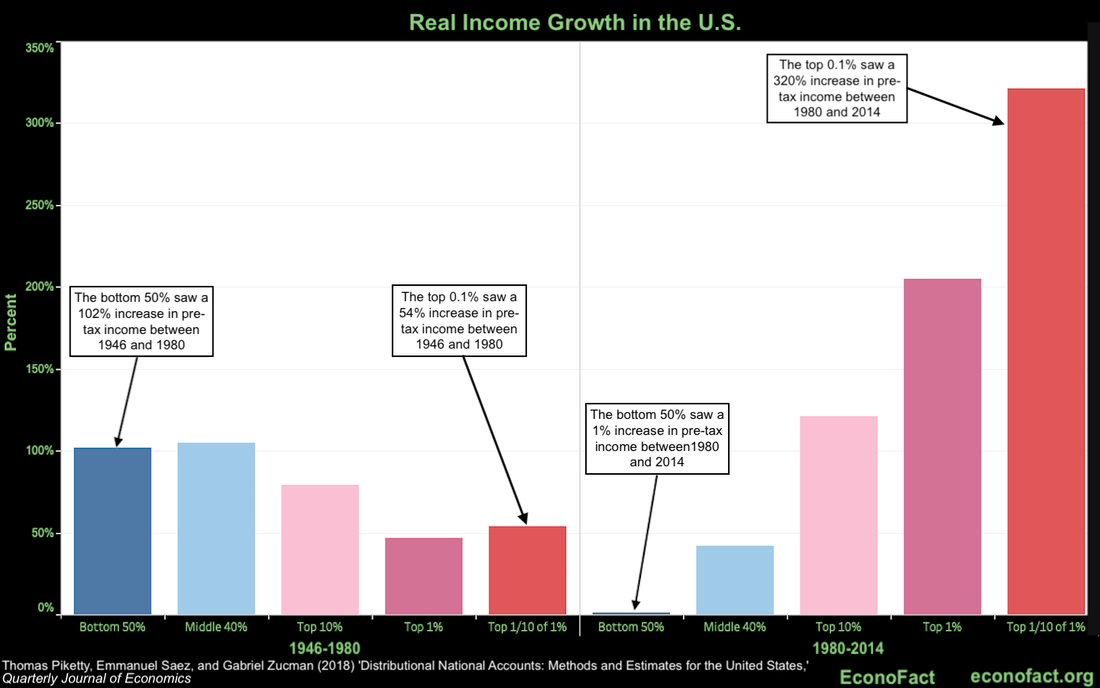

Piketty and Saez (2014) note that there are important differences between income and wealth inequality dynamics. First, wealth concentration is always much higher than income concentration.

The top 10 percent of wealth share typically falls in the 60 to 90 percent range of all wealth, whereas the top 10 percent income share is in the 30 to 50 percent range. The bottom 50 percent wealth share is always less than 5 percent, whereas the bottom 50 percent income share generally falls in the 20 to 30 percent range.

The bottom half of the population hardly owns any wealth, but it does earn appreciable income:The inequality of labor income can be high, but it is usually much less extreme. On average, members of the bottom half of the population, in terms of wealth, own less than one-tenth of the average wealth. The inequality of labor income can be high, but it is usually much less extreme.

Members of the bottom half of the population in income earn about half the average income. In sum, the concentration of capital ownership is always extreme, so that the very notion of capital is fairly abstract for large segments—if not the majority—of the population.

Piketty (2014) finds that wealth-income ratios, today, seem to be returning to very high levels in low economic growth countries, similar to what he calls the "classic patrimonial" wealth-based societies of the 19th century wherein a minority lives off its wealth while the rest of the population works for subsistence living. He surmises that wealth accumulation is high because growth is low.

See also:

- How Much More (Or Less) Would You Make If We Rolled Back Inequality? (January 2015). "How much more (or less) would families be earning today if inequality had remained flat since 1979?" National Public Radio

- OECD – Education GPS: Gender differences in education

- Civil rights

- Digital divide

- Educational inequality

- Gini coefficient

- Global justice

- Health equity

- Horizontal inequality

- List of countries by income inequality

- List of countries by distribution of wealth

- LGBT social movements

- Social apartheid

- Social equality

- Social exclusion

- Social mobility

- Social stratification

- Structural violence

- Tax evasion

- Triple oppression

Social Justice

- YouTube Video: What Does Social Justice Mean to YOU?

- YouTube Video: If I Could Change the World...

- YouTube Video: Listen: Dr. Maya Angelou Recites Her Poem "Phenomenal Woman"

Social justice is a concept of fair and just relations between the individual and society. This is measured by the explicit and tacit terms for the distribution of wealth, opportunities

for personal activity, and social privileges.

In Western as well as in older Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fulfill their societal roles and receive what was their due from society. In the current global grassroots movements for social justice, the emphasis has been on the breaking of barriers for social mobility, the creation of safety nets and economic justice.

Social justice assigns rights and duties in the institutions of society, which enables people to receive the basic benefits and burdens of cooperation. The relevant institutions often include the following:

Interpretations that relate justice to a reciprocal relationship to society are mediated by differences in cultural traditions, some of which emphasize the individual responsibility toward society and others the equilibrium between access to power and its responsible use.

Hence, social justice is invoked today while reinterpreting historical figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, in philosophical debates about differences among human beings, in efforts for gender, racial and social equality, for advocating justice for migrants, prisoners, the environment, and the physically and developmentally disabled.

While the concept of social justice can be traced through the theology of Augustine of Hippo and the philosophy of Thomas Paine, the term "social justice" became used explicitly in the 1780s. A Jesuit priest named Luigi Taparelli is typically credited with coining the term, and it spread during the revolutions of 1848 with the work of Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.

However, recent research has proved that the use of the expression "social justice" is older (even before the 19th century). For example, in Anglo-America, the term appears in The Federalist Papers, No. 7: "We have observed the disposition to retaliation excited in Connecticut in consequence of the enormities perpetrated by the Legislature of Rhode Island; and we reasonably infer that, in similar cases, under other circumstances, a war, not of parchment, but of the sword, would chastise such atrocious breaches of moral obligation and social justice."

In the late industrial revolution, progressive American legal scholars began to use the term more, particularly Louis Brandeis and Roscoe Pound. From the early 20th century it was also embedded in international law and institutions; the preamble to establish the International Labour Organization recalled that "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice."

In the later 20th century, social justice was made central to the philosophy of the social contract, primarily by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice (1971). In 1993, the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action treats social justice as a purpose of human rights education.

Some authors such as Friedrich Hayek criticize the concept of social justice, arguing the lack of objective, accepted moral standard; and that while there is a legal definition of what is just and equitable "there is no test of what is socially unjust", and further that social justice is often used for the reallocation of resources based on an arbitrary standard which may in fact be inequitable or unjust.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Social Justice.

for personal activity, and social privileges.

In Western as well as in older Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fulfill their societal roles and receive what was their due from society. In the current global grassroots movements for social justice, the emphasis has been on the breaking of barriers for social mobility, the creation of safety nets and economic justice.

Social justice assigns rights and duties in the institutions of society, which enables people to receive the basic benefits and burdens of cooperation. The relevant institutions often include the following:

- taxation,

- social insurance,

- public health,

- public school,

- public services,

- labor law and regulation of markets, to ensure fair distribution of wealth, and equal opportunity.

Interpretations that relate justice to a reciprocal relationship to society are mediated by differences in cultural traditions, some of which emphasize the individual responsibility toward society and others the equilibrium between access to power and its responsible use.

Hence, social justice is invoked today while reinterpreting historical figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, in philosophical debates about differences among human beings, in efforts for gender, racial and social equality, for advocating justice for migrants, prisoners, the environment, and the physically and developmentally disabled.

While the concept of social justice can be traced through the theology of Augustine of Hippo and the philosophy of Thomas Paine, the term "social justice" became used explicitly in the 1780s. A Jesuit priest named Luigi Taparelli is typically credited with coining the term, and it spread during the revolutions of 1848 with the work of Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.

However, recent research has proved that the use of the expression "social justice" is older (even before the 19th century). For example, in Anglo-America, the term appears in The Federalist Papers, No. 7: "We have observed the disposition to retaliation excited in Connecticut in consequence of the enormities perpetrated by the Legislature of Rhode Island; and we reasonably infer that, in similar cases, under other circumstances, a war, not of parchment, but of the sword, would chastise such atrocious breaches of moral obligation and social justice."

In the late industrial revolution, progressive American legal scholars began to use the term more, particularly Louis Brandeis and Roscoe Pound. From the early 20th century it was also embedded in international law and institutions; the preamble to establish the International Labour Organization recalled that "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice."

In the later 20th century, social justice was made central to the philosophy of the social contract, primarily by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice (1971). In 1993, the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action treats social justice as a purpose of human rights education.

Some authors such as Friedrich Hayek criticize the concept of social justice, arguing the lack of objective, accepted moral standard; and that while there is a legal definition of what is just and equitable "there is no test of what is socially unjust", and further that social justice is often used for the reallocation of resources based on an arbitrary standard which may in fact be inequitable or unjust.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about Social Justice.

- History

- Contemporary theory

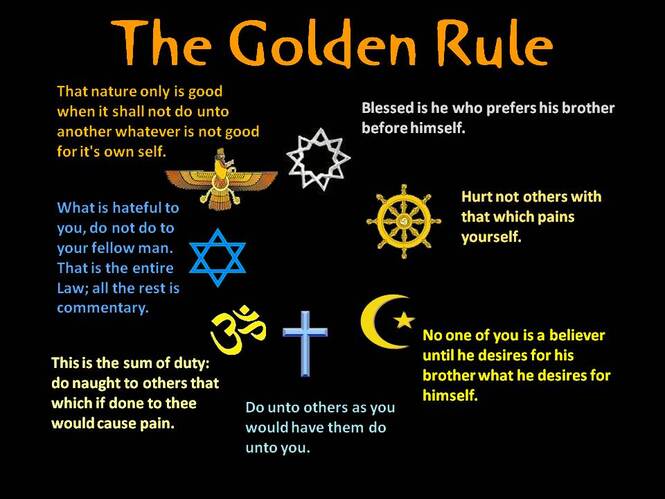

- Religious perspectives

- Social justice movements

- Criticism

- See also:

- Activism

- "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence", an anti-Vietnam war and pro-social justice speech delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1967

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Climate justice

- Economic justice

- Environmental justice

- Environmental racism

- Essentially contested concept

- Labor law and labor rights

- Left-wing politics

- Resource justice

- Right to education

- Right to health

- Right to housing

- Right to social security

- Socialism

- Social justice art

- Social justice warrior

- Social law

- Social work

- Solidarity

- Völkisch equality

- World Day of Social Justice

- All pages with titles beginning with Social justice

- All pages with titles containing Social justice

Race and ethnicity in the United States including a List by household income

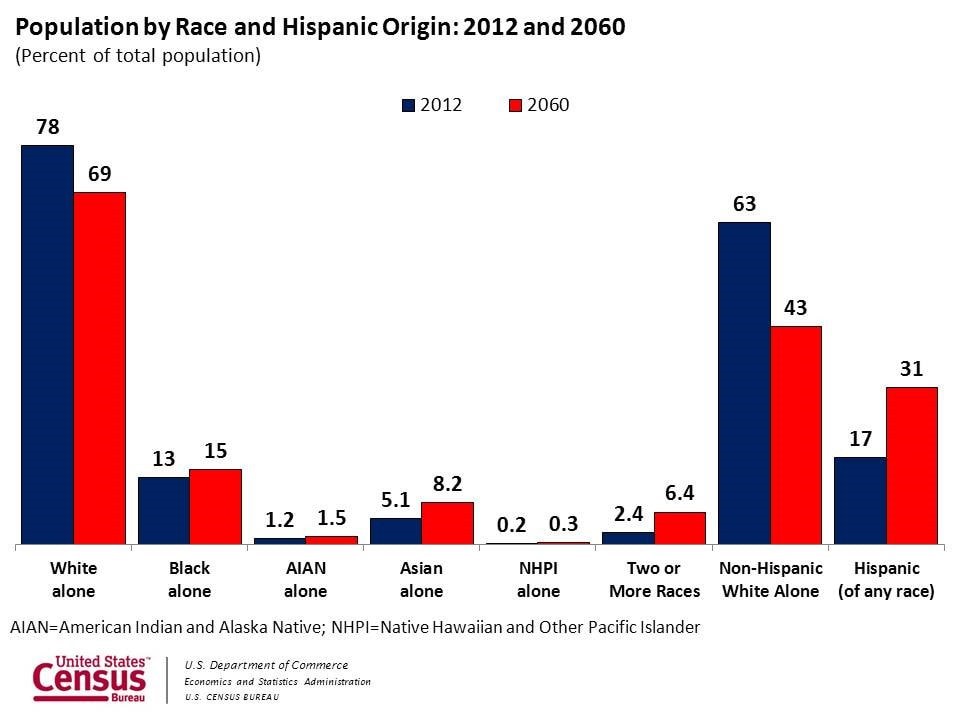

Pictured below: by Racial and Ethnic Makeup (L) Population; (R) Household Income

- YouTube Video: Poll: A majority of Americans think President Trump is a racist

- YouTube Video: Former President Obama unleashes on Trump, GOP - Full speech from Illinois

- YouTube Video: Is America Dreaming?: Understanding Social Mobility*

Pictured below: by Racial and Ethnic Makeup (L) Population; (R) Household Income

Click here for a List of racial and ethnic groups in the United States by household income.

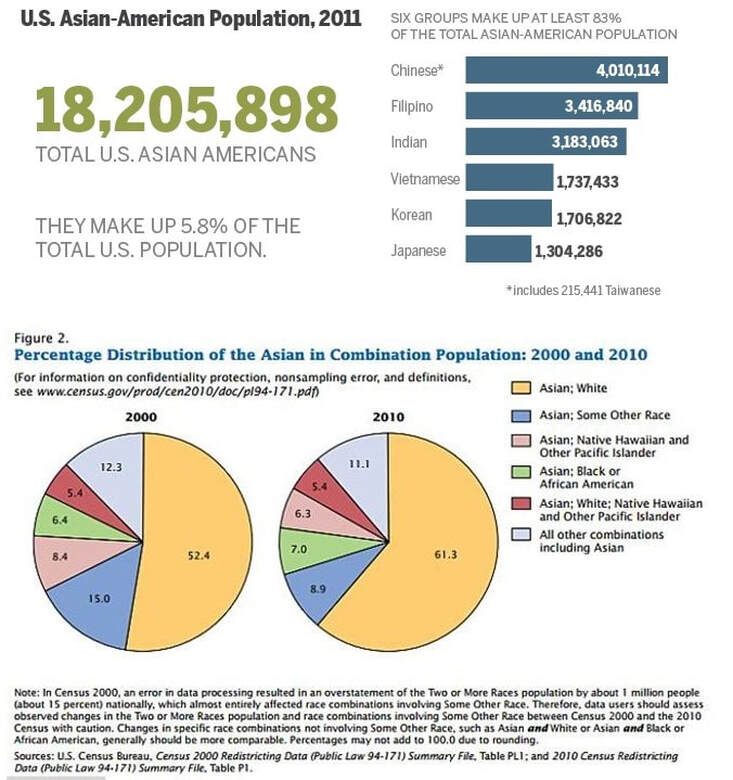

The United States has a racially and ethnically diverse population. The United States Census officially recognizes six racial categories:

The United States Census Bureau also classifies Americans as "Hispanic or Latino" and "Not Hispanic or Latino", which identifies Hispanic and Latino Americans as an ethnicity (not a race) distinct from others that composes the largest minority group in the nation.

The United States Supreme Court unanimously held that "race" is not limited to Census designations on the "race question" but extends to all ethnicities, and thus can include Jewish and Arab as well as Polish or Italian or Irish, etc. In fact, the Census asks an "Ancestry Question" which covers the broader notion of ethnicity initially in the 2000 Census long form and now in the American Community Survey.

White Americans are the racial majority. African Americans are the largest racial minority, amounting to 13.2% of the population. Hispanic and Latino Americans amount to 17% of the population, making up the largest ethnic minority. The White, non-Hispanic or Latino population make up 62.6% of the nation's total, with the total White population (including White Hispanics and Latinos) being 77%.

White Americans are the majority in every region except Hawaii, but contribute the highest proportion of the population in the Midwestern United States, at 85% per the Population Estimates Program (PEP), or 83% per the American Community Survey (ACS).

Non-Hispanic Whites make up 79% of the Midwest's population, the highest ratio of any region. However, 35% of White Americans (whether all White Americans or non-Hispanic/Latino only) live in the South, the most of any region.

55% of the African American population lives in the South. A plurality or majority of the other official groups reside in the West. This region is home to 42% of Hispanic and Latino Americans, 46% of Asian Americans, 48% of American Indians and Alaska Natives, 68% of Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, 37% of the "two or more races" population (Multiracial Americans), and 46% of those designated "some other race".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for moire about Race and Ethnicity in the United States:

The United States has a racially and ethnically diverse population. The United States Census officially recognizes six racial categories:

- White American,

- Black or African American,

- Native American and Alaska Native,

- Asian American,

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander,

- People of two or more races; a category called "some other race" is also used in the census and other surveys, but is not official.

The United States Census Bureau also classifies Americans as "Hispanic or Latino" and "Not Hispanic or Latino", which identifies Hispanic and Latino Americans as an ethnicity (not a race) distinct from others that composes the largest minority group in the nation.

The United States Supreme Court unanimously held that "race" is not limited to Census designations on the "race question" but extends to all ethnicities, and thus can include Jewish and Arab as well as Polish or Italian or Irish, etc. In fact, the Census asks an "Ancestry Question" which covers the broader notion of ethnicity initially in the 2000 Census long form and now in the American Community Survey.

White Americans are the racial majority. African Americans are the largest racial minority, amounting to 13.2% of the population. Hispanic and Latino Americans amount to 17% of the population, making up the largest ethnic minority. The White, non-Hispanic or Latino population make up 62.6% of the nation's total, with the total White population (including White Hispanics and Latinos) being 77%.

White Americans are the majority in every region except Hawaii, but contribute the highest proportion of the population in the Midwestern United States, at 85% per the Population Estimates Program (PEP), or 83% per the American Community Survey (ACS).

Non-Hispanic Whites make up 79% of the Midwest's population, the highest ratio of any region. However, 35% of White Americans (whether all White Americans or non-Hispanic/Latino only) live in the South, the most of any region.

55% of the African American population lives in the South. A plurality or majority of the other official groups reside in the West. This region is home to 42% of Hispanic and Latino Americans, 46% of Asian Americans, 48% of American Indians and Alaska Natives, 68% of Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, 37% of the "two or more races" population (Multiracial Americans), and 46% of those designated "some other race".

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for moire about Race and Ethnicity in the United States:

- Racial and ethnic categories

- Social definitions of race

- Historical trends and influences

- Racial makeup of the U.S. population

- Ancestry

- See also:

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the United States had an estimated population of 328,239,523 in 2019 (with an unofficial statistical adjustment to 329,484,123 as of July 1, 2020 ahead of the final 2020 Census).

The United States is the third most populous country in the world, and current projections from the unofficial U.S. Population Clock show a total of just over 330 million residents.

All these figures exclude the population of five self-governing U.S. territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands) as well as several minor island possessions.

The Census Bureau showed a population increase of 0.75% for the twelve-month period ending in July 2012. Though high by industrialized country standards, this is below the world average annual rate of 1.1%. The total fertility rate in the United States estimated for 2019 is 1.706 children per woman, which is below the replacement fertility rate of approximately 2.1.

The U.S. population almost quadrupled during the 20th century—at a growth rate of about 1.3% a year—from about 76 million in 1900 to 281 million in 2000. It is estimated to have reached the 200 million mark in 1967, and the 300 million mark on October 17, 2006.

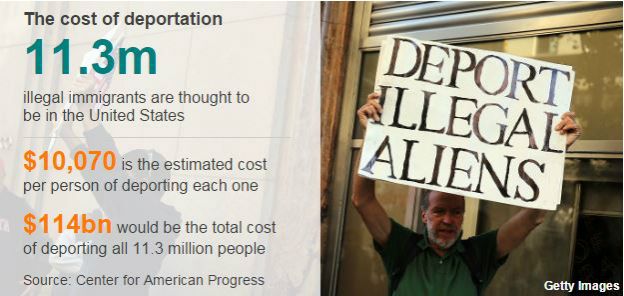

Foreign-born immigration has caused the U.S. population to continue its rapid increase, with the foreign-born population doubling from almost 20 million in 1990 to over 45 million in 2015, representing one-third of the population increase.

Population growth is fastest among minorities as a whole, and according to the Census Bureau's estimation for 2020, 50% of U.S. children under the age of 18 are members of ethnic minority groups.

White people constitute the majority of the U.S. population, with a total of about 234,370,202 or 73% of the population as of 2017. Non-Hispanic Whites make up 60.7% of the country's population. Their share of the U.S. population is expected to fall below 50% by 2045, primarily due to immigration and low birth rates.

Hispanic and Latino Americans accounted for 48% of the national population growth of 2.9 million between July 1, 2005, and July 1, 2006. Immigrants and their U.S.-born descendants are expected to provide most of the U.S. population gains in the decades ahead.

The Census Bureau projects a U.S. population of 417 million in 2060, a 38% increase from 2007 (301.3 million), and the United Nations estimates that the U.S. will be among the nine countries responsible for half the world's population growth by 2050, with its population being 402 million by then (an increase of 32% from 2007).

In an official census report, it was reported that 54.4% (2,150,926 out of 3,953,593) of births in 2010 were to "non-Hispanic whites". This represents an increase of 0.3% compared to the previous year, which was 54.1%.

Click on any of the following blue hyperlinks for more about the Demographics of the United States:

The United States is the third most populous country in the world, and current projections from the unofficial U.S. Population Clock show a total of just over 330 million residents.

All these figures exclude the population of five self-governing U.S. territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands) as well as several minor island possessions.

The Census Bureau showed a population increase of 0.75% for the twelve-month period ending in July 2012. Though high by industrialized country standards, this is below the world average annual rate of 1.1%. The total fertility rate in the United States estimated for 2019 is 1.706 children per woman, which is below the replacement fertility rate of approximately 2.1.

The U.S. population almost quadrupled during the 20th century—at a growth rate of about 1.3% a year—from about 76 million in 1900 to 281 million in 2000. It is estimated to have reached the 200 million mark in 1967, and the 300 million mark on October 17, 2006.